Reason for Drawings

Have you ever wondered what would happen if a certain drawing did NOT exist? I am forever grateful to Cedric Price for doing this drawing. If he had not done it, my job of devising a way to order and organise materials for what became Cedric Price Works 1952-2003: a forward-minded retrospective (AA/CCA, 2016) would have been a whole lot more complicated or perhaps, more distressingly, contrived. The two-volume box set was the output of a ten-year long research, writing and production process that brought together all two hundred and thirty plus projects by Price into one publication for the first time.

The complications of writing and producing this work were perhaps not unlike many other monographic projects that are generated from primary source materials. Useful information was, in the main, drawn from the office job files of Cedric Price Architects, from amongst associated office paraphernalia such as diaries and library and personal files, and found in conversations with friends, colleagues and commentators. I first consulted the files whilst working on an earlier, slimmer publication—Cedric Price Opera (Wiley, 2003)—and when Price was still in residence at his offices at 38 Alfred Place in Bloomsbury. Documents were loosely organised according to job number (although there were often deliberate gaps in their numbering sequence, the logic for which was never entirely clear), and I had a free rein to look in drawing-packed plan chests with Cedric there to help identify what was what (although his accounts contained many gaps which turned out to be deliberate also). During that period, the contents of the office were acquired by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal. All the files, roles, books and boxes—almost 20,000 drawings, 34 linear metres of textual records and more—were packed up in two consignments and moved to Montreal, leaving four empty floors in time for the office to close in 2001. Then, in 2003, Cedric was gone too.

The CCA archivists immediately assigned an initial numbering structure and system that broadly identified job boxes as containing ‘papers’, ‘correspondence’, and/or a range of drawing types. This was not the moment for a more detailed listing—I soon discovered that’s what scholars are for—although some of the more well-known work was easily identifiable and labelled at this stage. When the time came to embark on the ‘Works’ publication in 2009, it made searching the archive lists a little like a game of Bingo and a lot like engaging in detective work. My plan was to work through the office job list chronologically and piece together what, why and how each project came about through studying correspondence, drawings and related ephemera or documents. There was the yet unsolved question of how to select and then order relevant drawings to accompany each project that would give a strong sense of Price’s theory and process—important as this was not going to be a book full of glossy photographs of finished buildings.

I had good days and bad days. The bad ones were when a number of boxes of papers were brought up from the vaults that contained many, many photocopies of the same map or set of brief documents, adding little to writing the story of a project (other than the interesting impact that the Xerox machine had had on the design and administrative processes at the time—but that was not my focus). A good day was like the one when I selected some boxes from the Personal/Miscellaneous series simply to find out what Price would consider to be ‘miscellaneous’—various, different, assorted, jumbled—words that fit with Price’s architectural ideas about indeterminacy, uncertainty and delighting in doubt…. and there it was! One piece of folded, yellowed paper caught my eye. It was tucked amongst a folder of other assorted paper types and sizes, waiting patiently but poking up above the rest. On unfolding, it turned into a single landscape sheet of the out-stretched proportion commonly in use in Price’s office and contained a black crayon sketch diagram made of words and cartoons entitled Reason for Drawings. Bingo!

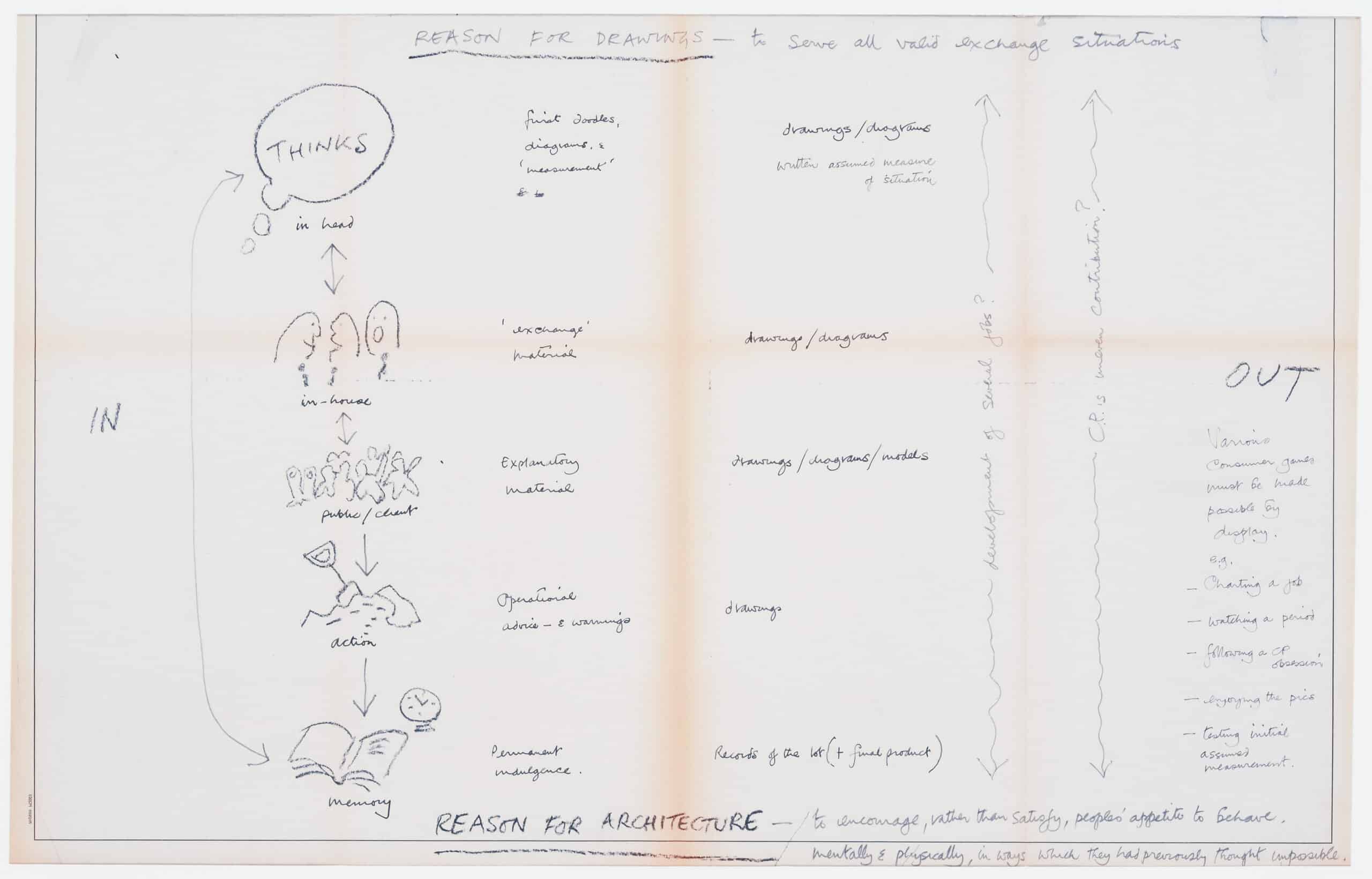

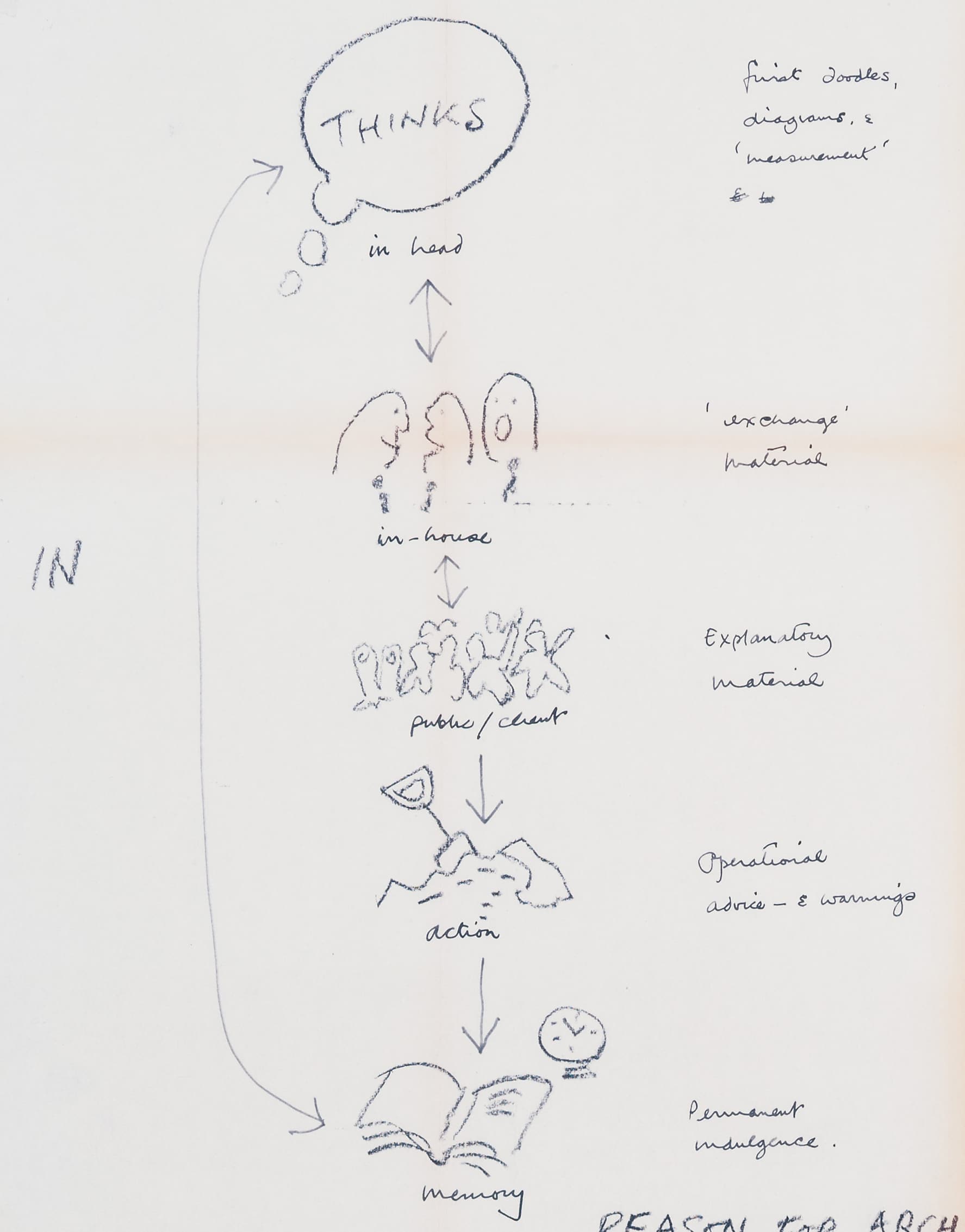

That single piece of paper held the answer to what became the underlying logic for each project layout in the ‘Works’ publication. It gives a straightforward description of how Price’s drawings were used to ‘serve all valid exchange situations’. Arranged vertically each drawing type is accompanied by a cartoon image to illustrate the point. Price starts at the top with ‘in-head’, followed by ‘in-house’, then ‘public/client’, ‘action’ and ‘memory drawings’ at the bottom of the sheet. A big arrow points us back up to the top for the process to begin again. It shows a circular process that captures the best parts of ideas and experiences for future use. Additional notes embellish each category: ‘in-head’ drawings are ‘first doodles, diagrams and ‘measurement’ [of a situation]; ‘in-house’ drawings are ‘exchange material’ for talking to members of the office; ‘public/client’ drawings are ‘explanatory material’; ‘action’ drawings are ‘operational, advice – and warnings’; and ‘memory’ drawings are a ‘permanent indulgence – a record of the lot’. There are other notes too—take a look and see what you can find.

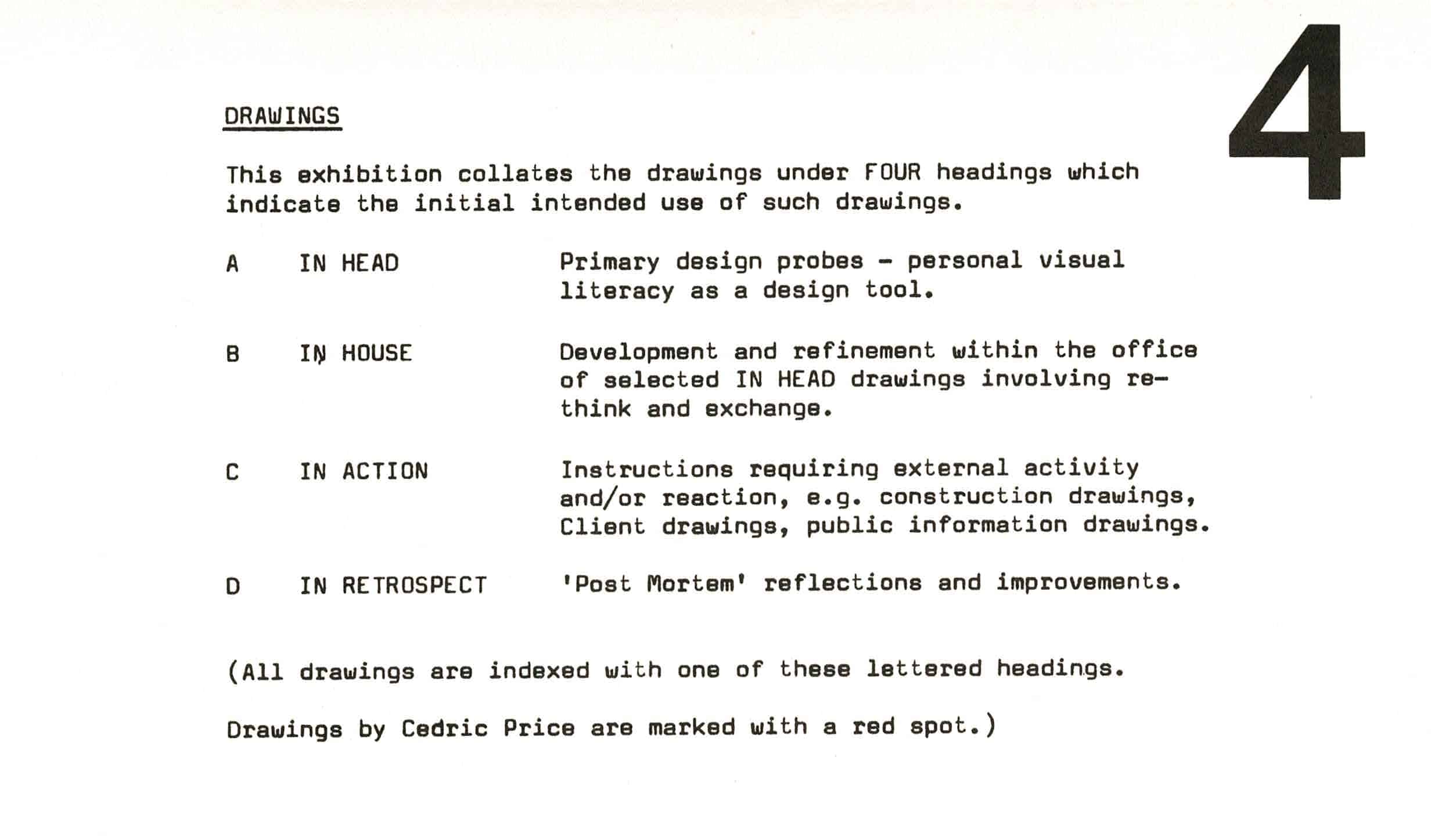

The drawing categories were summarised later in a catchier manner for an exhibition on Price’s work called The Evolving Image, at the RIBA Heinz Gallery, London 8 October – 29 November 1975: ‘in head’, ‘in house’, in a crowd’, ‘in retrospect’. A sheet of pink paper (a carbon copy whose companion yellow sheet would have been sent to the correspondent) also offers the following explanation: ‘Price considers drawings as both design tools and a(sic) communication forms requiring varying degrees of visual literacy from the users. He has no interest in establishing syntatic(sic) graphic sets.’ Price was suggesting that rather than his categories being absolute (syntactic), his reason for choosing to make or deploy a certain kind of drawing was always with the user, intended recipient or audience in mind.

These sheets not only gave form and structure to the visual content in my publication, they contributed something to the title too—a forward-minded retrospective describes the timeless loop of rethinking and reworking of design processes. Every time I look at these sheets, I ask myself, does Cedric mean ‘the reason for drawings’ or ‘drawing is a kind of reasoning’ or is he ‘weighing up’ the thought for which we have only half the proposition: ‘reason for drawing/drawing for reason’? It doesn’t really matter other than that he prompts these questions, and he made the drawing.

*

Samantha Hardingham is an architectural educator, author, curator and researcher. She has completed two further books and curated associated exhibitions on the work of British architect Cedric Price (1934–2003): Cedric Price Opera (Academy Wiley, 2003), Cedric Price Retriever (InIVa, 2007) and Cedric Price – The Dynamics of Time (Bureau Europa, Maastricht, 2014). She was visiting scholar at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal (2009) studying the Price archive. Hardingham was a senior research fellow at the University of Westminster (2003–08) and is currently a design studio lead there. She has also led design studios at the Architectural Association (2006-2017) and the London School of Architecture (2022-24).