Lisson to Tony Fretton

15 December 2023

– Tony Fretton and Ricardo Aboim Inglez

Tony Fretton founded his architectural practice (Tony Fretton Architects) in 1982 in London. He came into international prominence in 1991 after the completion of the second Lisson Gallery building, transforming the street into an urban setting to be absorbed by culture. From his house in London and over two hours, we talked about his architectural upbringing and his experience in performance art that led to both Lisson Gallery projects.

Ricardo Aboim Inglez (RAI): You were born in 1945 in a country still at war. East London, where you grew up, was one of the many sites devasted by the 1940 and 1941 German air raids, known as the Blitz. There were probably still signs of destruction all over the city when you were growing up. Did these affect the way you look at things?

Tony Fretton (TF): Not really. It was a moment of incredible optimism. The rebuilding of the economy after the Second World War created jobs. It was a time of early consumerism and working people had possessions. As the children of the working people, we received money to study, so all my fees and living expenses were paid. People from a working background started to emerge into the culture world, as actors, artists, architects, musicians. The time it became less good was in the mid-1970s, when I think, across Europe, the thirty glorious years came to an end, and the corporate state ran out of road. Margaret Thatcher is usually blamed for what came next but the left-wing government in Britain had also run out of ideas and couldn’t fund an expansion of the welfare state. The 1970s, when I was 35, had a very different, more negative mood than the 1960s. London still had an underdeveloped quality. What you see now, is a result of Reagan and Thatcher’s monetarisation of property. In the 1970s there were still empty houses, where you could squat. I lived in one of those for a while and practised with the post-punk band I played in.

RAI: What instrument did you play?

TF: I played the guitar. It was post-punk, so you didn’t have to play very well. Nial, one of my friends that was in the band just told me that he finished one of the songs that we wrote together, forty years later. He’s going to publish it. It looks as though I might get royalties and I can’t even remember the song!

RAI: Are you going to tour the country and play on gigs?

TF: No! You have parts of your life when you do things, and then you change. The aesthetics of the 1970s was raw, like London then, unfinished, and damaged. Strangely this mood led to my design of the Lisson Gallery. People like Nicholas Logsdail and his gallery, the Lisson, were newly emerging. There was a revival of interest in 1960s American conceptual artists such as Carl Andre, Donald Judd and Dan Graham, who I knew, had a second life. The Lisson Gallery showed those artists and new British artists, who were about five years younger than me, like Anish Kapoor, Richard Deacon, and Tony Cragg. I had been practising for a while and was then able to reflect on my approach to architecture to turn my dissatisfaction with it into something positive. I wanted to make architecture that had the freedom and political engagement I found in the music and performance in which I was engaged and the contemporary art that I admired, and was completely different to post-modernism. Robert Venturi’s work of the early 1970s was very punk and aligned with conceptual art. By the time I was working in an office, it had become grotesque and at the service of the establishment.

RAI: In the early 1970s, Rogers and Foster started building quite interesting projects. Were you not intrigued by their work?

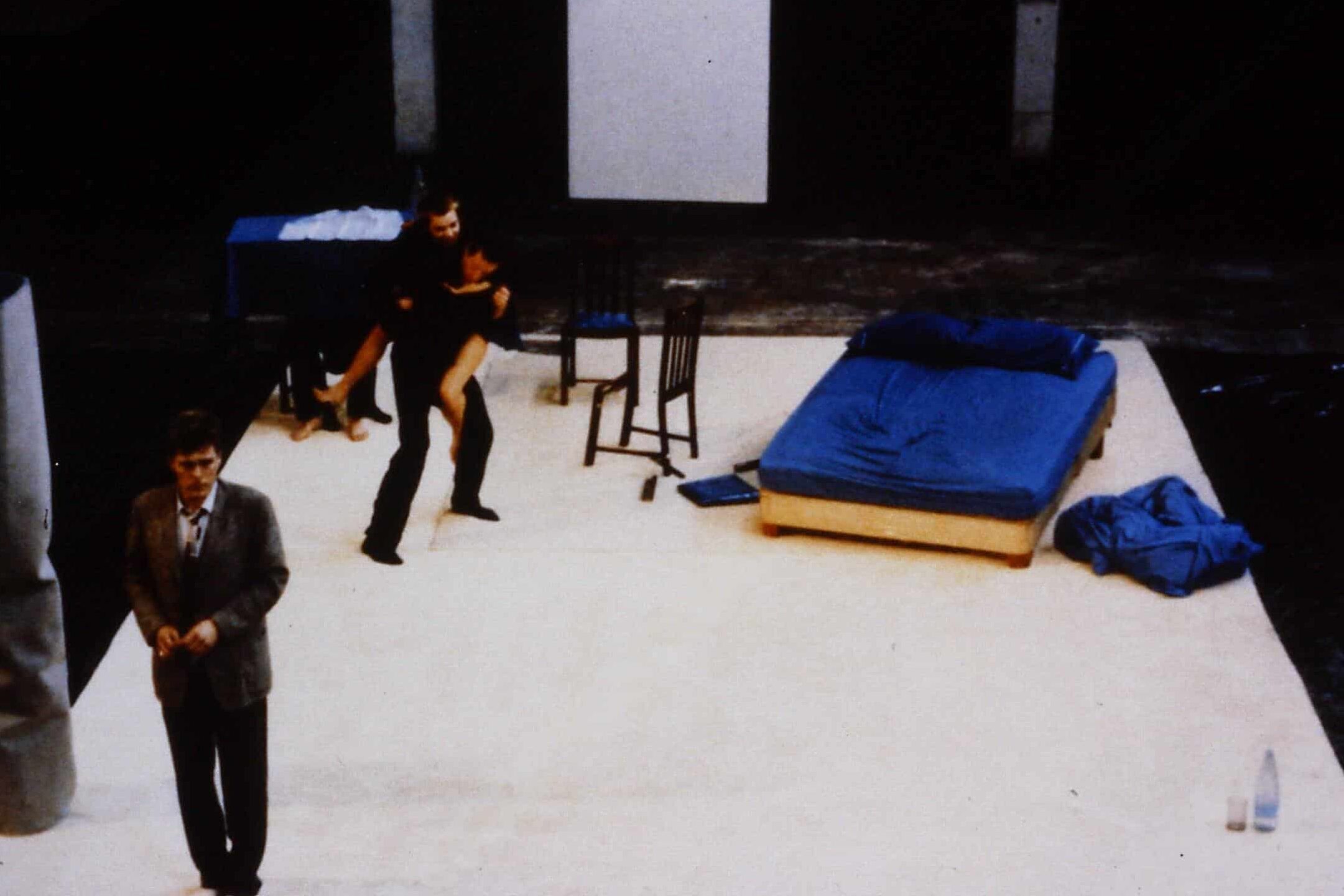

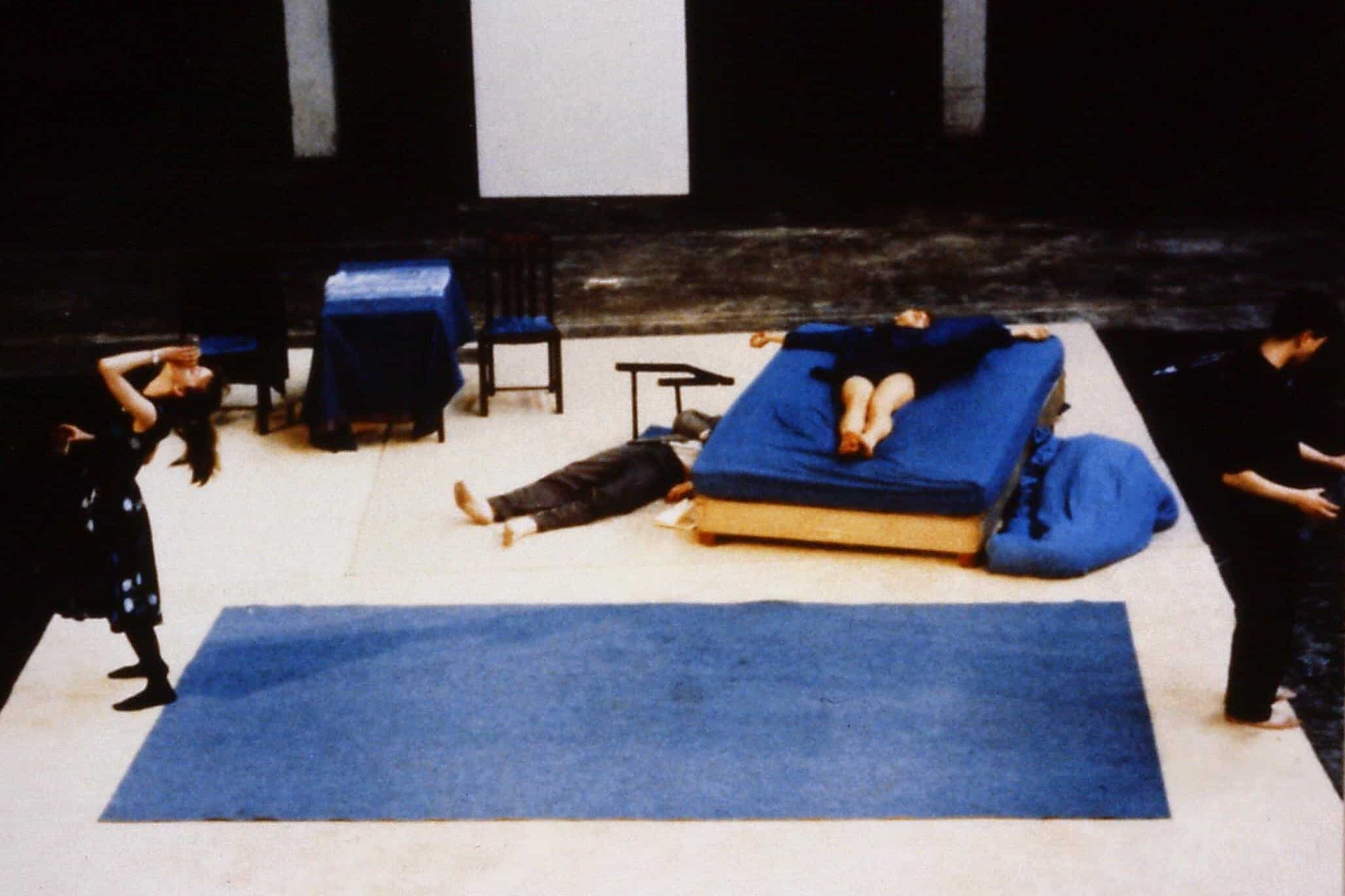

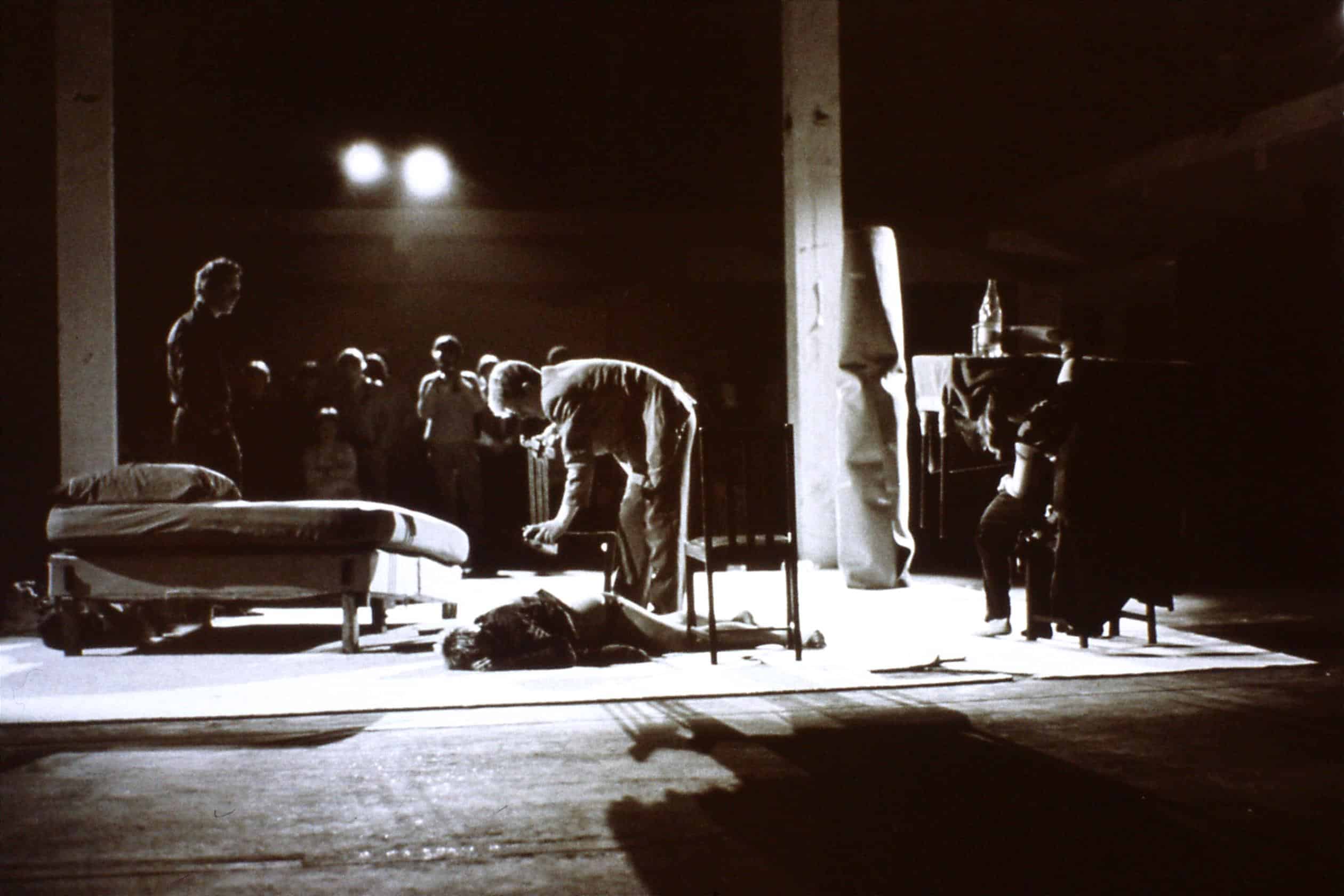

TF: Modernism could have continued to develop, as it did, in the hands of Foster and Rogers. There would have been an optimistic forward-looking modernism, which incorporated ideas of place and consumerism. I declined a job at Foster’s because I was in love with another state of mind. I was living on next to nothing and the exposure to basic existence was very exciting. By chance, I saw a performance by a company called Station House Opera which amazed me. I asked if I could join them and within a month, I was in Paris playing an architect in a performance. I realised that performance was using most of the same materials as in architecture: place, objects of use, conventional gestures, and speech, but in the broadest sense, were revealing their cultural backgrounds. I began to see that the materials and modes of architecture could be viewed and used in a similar way, and I was able to realise this in the first Lisson Gallery building of 1986. The sketchbooks of this building that are in the Drawing Matter Collection and their publication Fretton 3 show how I worked this out.

RAI: I believe that rather than attending the university, at the age of eighteen, you have worked in construction, which gives you a different background compared to most architects.

TF: When I worked in construction, the excavations in the ground and the brick-stacked top were more beautiful than the finished building.

RAI: You then attended the AA from 1966 to 1972 in what must have been a very interesting period. The Hippie movement was making way for recreational drugs, Pink Floyd under Syd Barrett started their psychedelic journey and by the time you graduated, The Velvet Underground were almost finished. How was the AA at that time?

TF: I had a mixed relationship with it. I had worked before studying and I thought I would learn something concrete…. I had a very good first year led by Elia Zenghelis, and two excellent years with James Gowan as my teacher. In the second year, I had to leave for a year, and I worked for Arup Associates, where I understood something about architecture.

RAI: As a foreigner, I sense that the AA tends to draw students into a speculative vision of architecture. My impression of Gowan is that he relied on the very basis of architecture, such as space, construction, meaning, and poetics. Wasn’t he misplaced at the AA?

TF: All the teachers at the AA were misplaced. At the time, there was a structural change. Michael Lloyd, the head of the AA, changed from a year system, where you had a didactic centre to a unit system, which has created a school that is a supermarket of ideas. That was very difficult to deal with. It places the choice of direction on the students, taking away one of the responsibilities to educate. With Gowan it was very clear. He always started with what the student could produce and then showed them the intellectual questions that lay in their work.

RAI: You left the AA in 1972 and went on to work for several practices. During your time at these practices, Punk exploded in New York and later in London…

TF: No, it exploded in London.

RAI: I thought the Ramones were earlier in New York…

TF: Well, it might have been, but they weren’t real punks.

RAI: How was London in those days?

TF: Sensational, completely wonderful!

RAI: Upon leaving the Station Opera House performance company, you returned to architecture, presumably invigorated, from the experience…

TF: I returned sadly and with regret.

RAI: You set up your own practice in 1982. From 1982 to 1986, the year Lisson Gallery 1 opened, I only found one project record of yours, and that’s Mute Records. It seems that you were always consistently drawn to the same direction: art, music, and performance art.

TF: I was. There was a period between 1982 and 1986 when I just did small jobs for people. I didn’t have the creative formation I described to you. I was just doing it. Although it wasn’t bad work, I have never published it and I have destroyed all the drawings.

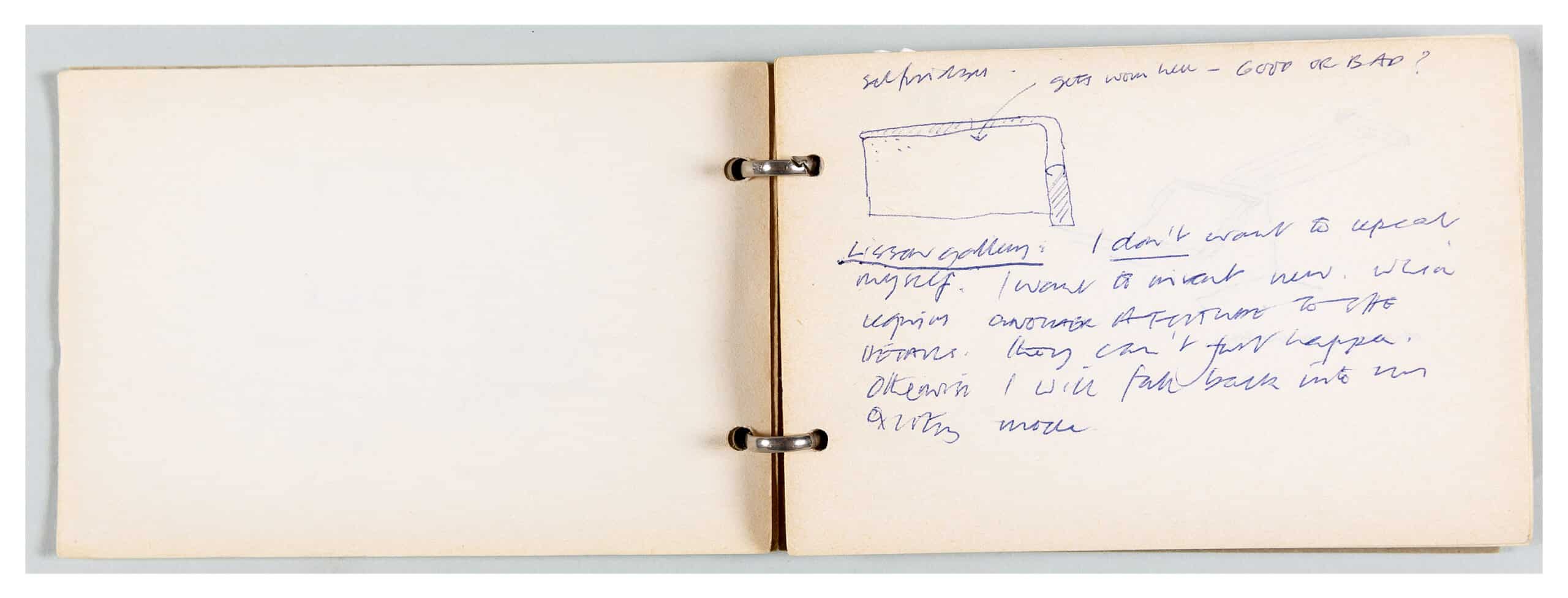

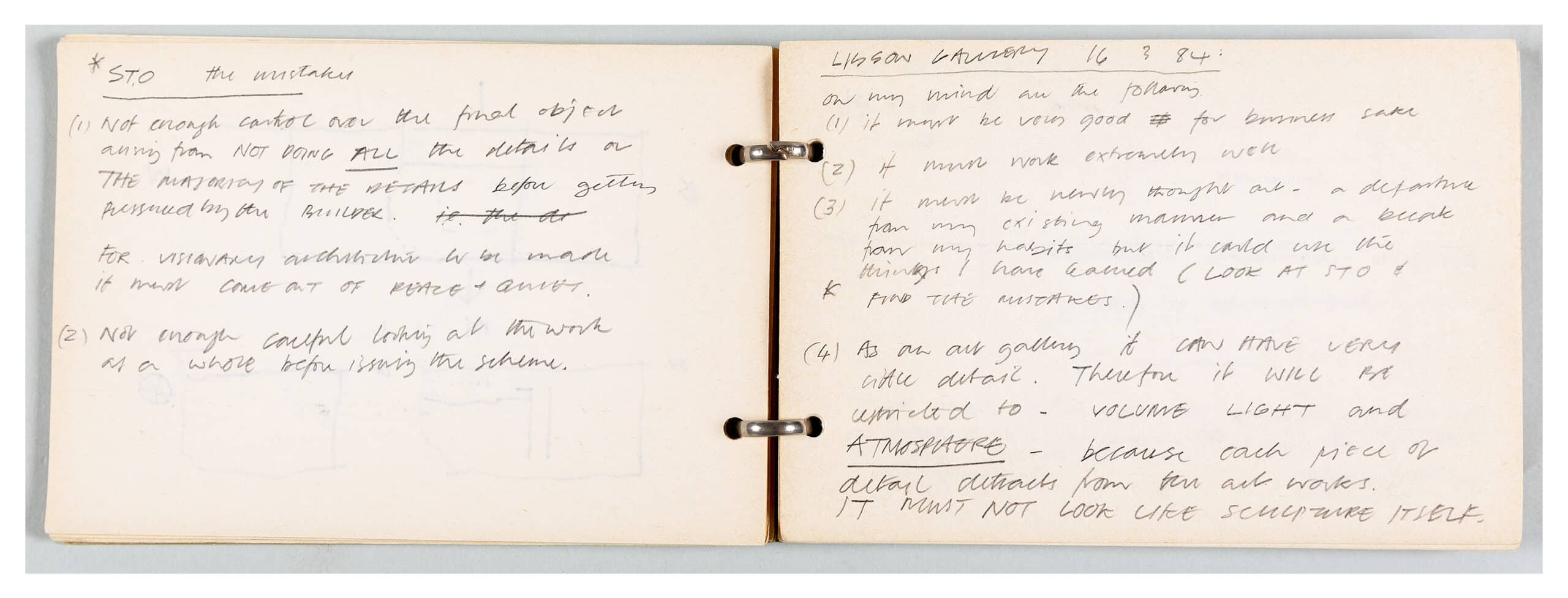

RAI: Drawing Matter holds all your sketchbooks for both Lisson Gallery projects. Going through them, one can read your notes and, from time to time, catch a glimpse of your inner thoughts. The sketchbook from March 1984, labelled as ‘Lisson 1, First Ideas’, provides us with such glimpses.

‘Lisson Gallery: I don’t want to repeat myself. I want to invent new. Which requires ANOTHER ATTITUDE TO THE DETAILS. They can’t just happen. Otherwise, I will fall back into my existing mode.’

Also, these other two:

‘ST.O [Saint Oswald’s Place] The mistakes

(1) Not enough control over the final object arising from NOT DOING ALL the details or THE MAJORITY OF THE DETAILS before getting pressured by the BUILDER.

FOR VISIONARY ARCHITECTURE TO BE MADE IT MUST COME OUT OF PEACE + QUIET.

(2) Not enough careful looking at the work as a whole before issuing the scheme.’

TF: Did I really write that? It’s revealing…

RAI: Then you move forward to Lisson:

‘On my mind are the following:

(1) It must be very good for business sake

(2) It must work extremely well

(3) It must be newly thought out – a departure from my existing manner and a break from my habits but it could use the things I have learned (look at ST.O & find the mistakes)

(4) As an art gallery it can have very little detail. Therefore, it will be limited to – volume light and ATMOSPHERE – because each piece of detail distracts from the art works.

IT MUST NOT LOOK LIKE SCULPTURE ITSELF.’

Considering that at the time you were 39 years old, and you had ample time to mature as an individual, upon reading your notes, one is firstly struck by the ongoing dialogue you maintain with yourself, almost self-penalizing and self-motivating. Additionally, the clarity of your realization that this project can be your breakthrough is evident—not merely for the sake of business speaking as you wrote. Now, that almost 40 years have gone by, what’s your view on these remarks today?

TF: I think they were honourable and there was good work. When I did it, I did it volitionally. I did it without thinking. I understood something. Interestingly, the younger generation of architects, like Caruso St John, saw a lot in the Lisson Gallery, which changed their position.

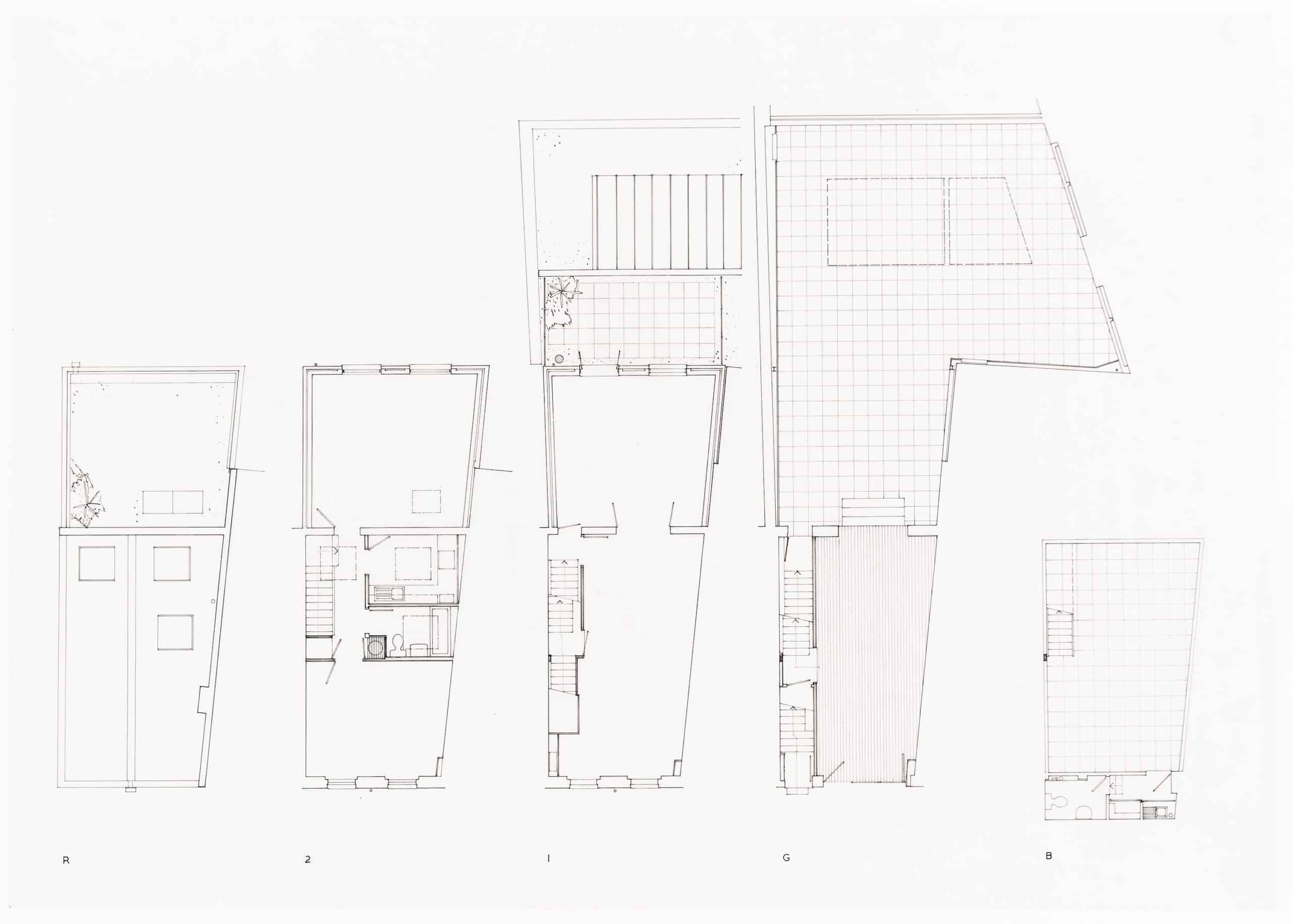

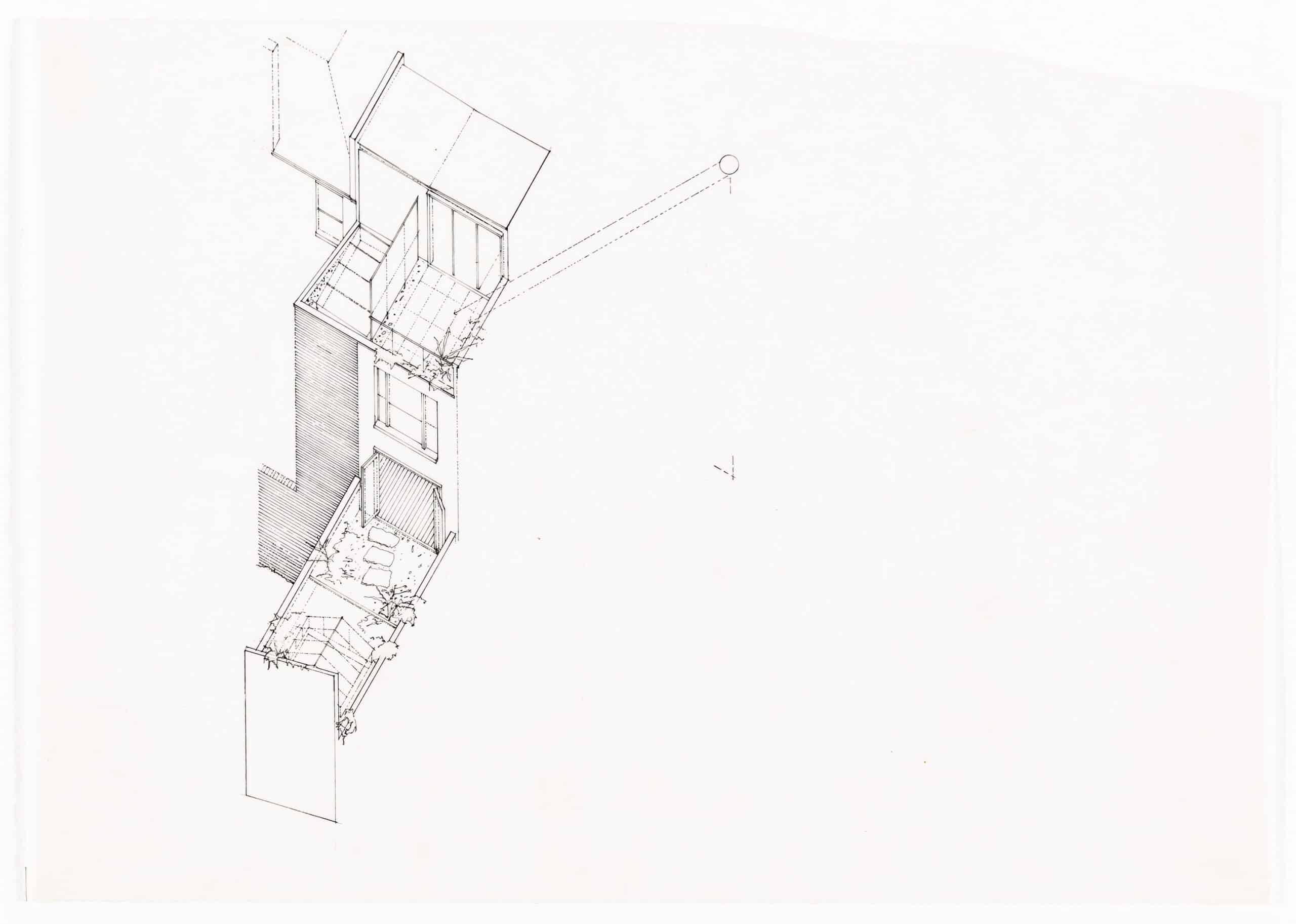

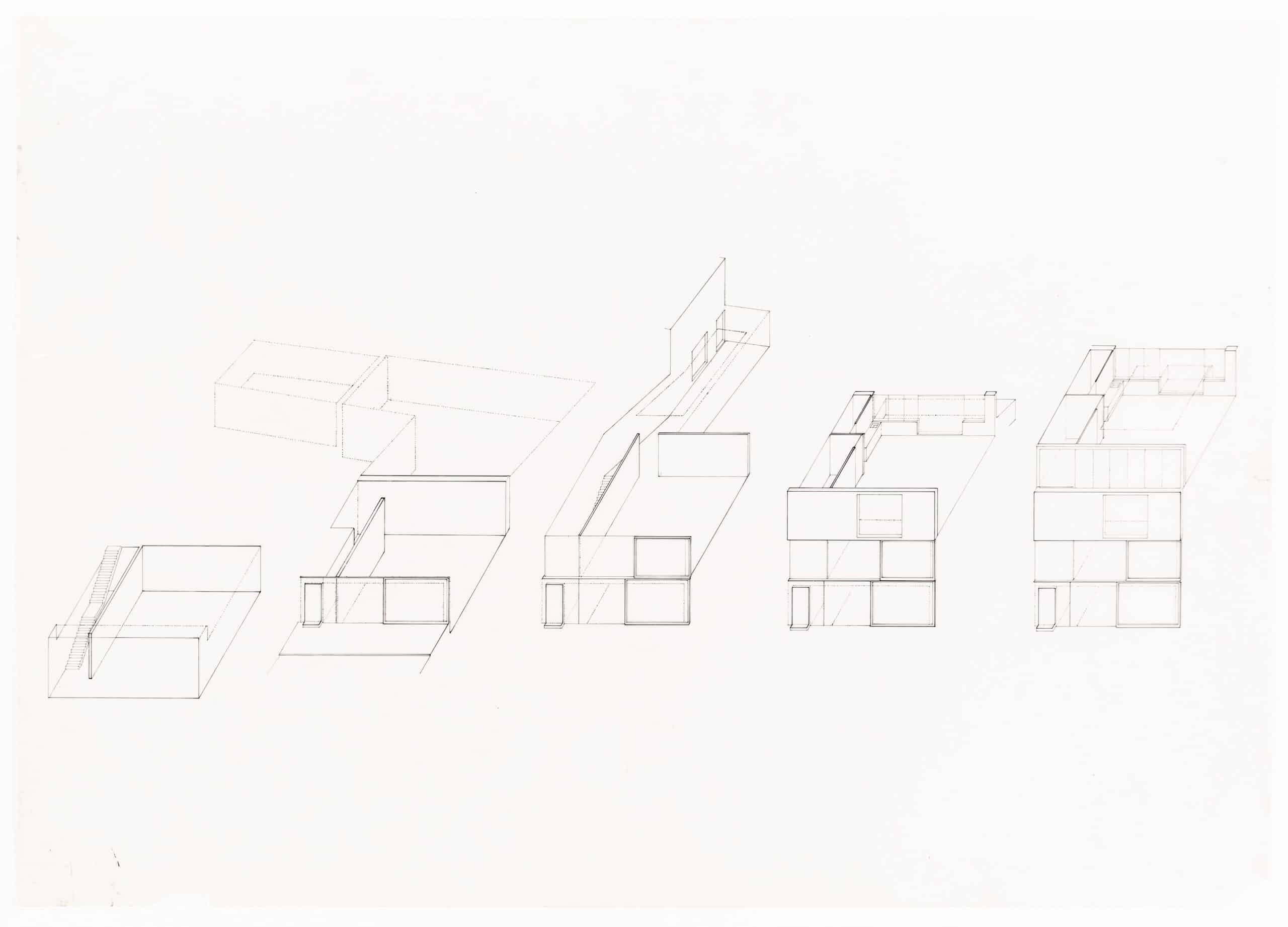

RAI: I am handing you copies of what I believe to be the material you have produced for presentation purposes.

TF: These were also produced to show the project to myself, to understand it, as architecture and to absorb what I had done.

RAI: Analysing these drawings, one has different positive feelings. On one hand, it appears that all the project effort was focused on designing a housing building. On the other hand, it seems as though you embraced the white gallery architecture of the time but with different intentions. Looking at the rear elevation, which comprises a cross-section through the gallery, one can clearly visualize the white cube statement together with a residential building. If we are to go back to the plan, there’s this feeling of a tilled garage-looking-like space, which gives it a punk atmosphere as well as character and neutrality. What do you think about these observations?

TF: Well, I wouldn’t see it as a punk statement. The architecture that came out was uninfluenced. It was originated by me. I didn’t want to make a punk architecture. I wanted to make an architecture that was forward-looking and communicative with people and that wasn’t demonstrative. For the elevations that you mention, I was interested in the very abstract quality that late Georgian buildings have and that is a large part of London. It’s a deeply embedded type. It originated a long time ago and it just has been worked and reworked. I wanted to be part of that.

RAI: By 1989 you were already working on the second Lisson Gallery 2, an extension to the previously designed gallery. However, this time it took the form of a newly constructed building. It becomes apparent that the project follows a similar thematic direction as before, albeit in a reversed order. This reversion is well illustrated in the axonometric plans, indicating the construction of a gallery with a residential unit on top. Was this arrangement premeditated?

TF: No, it was part of the legislation that you couldn’t build complete office space. They wanted to preserve some residential in the area. They wanted a mixed-use, which is what we provided. But it was designed so it could be used as office space.

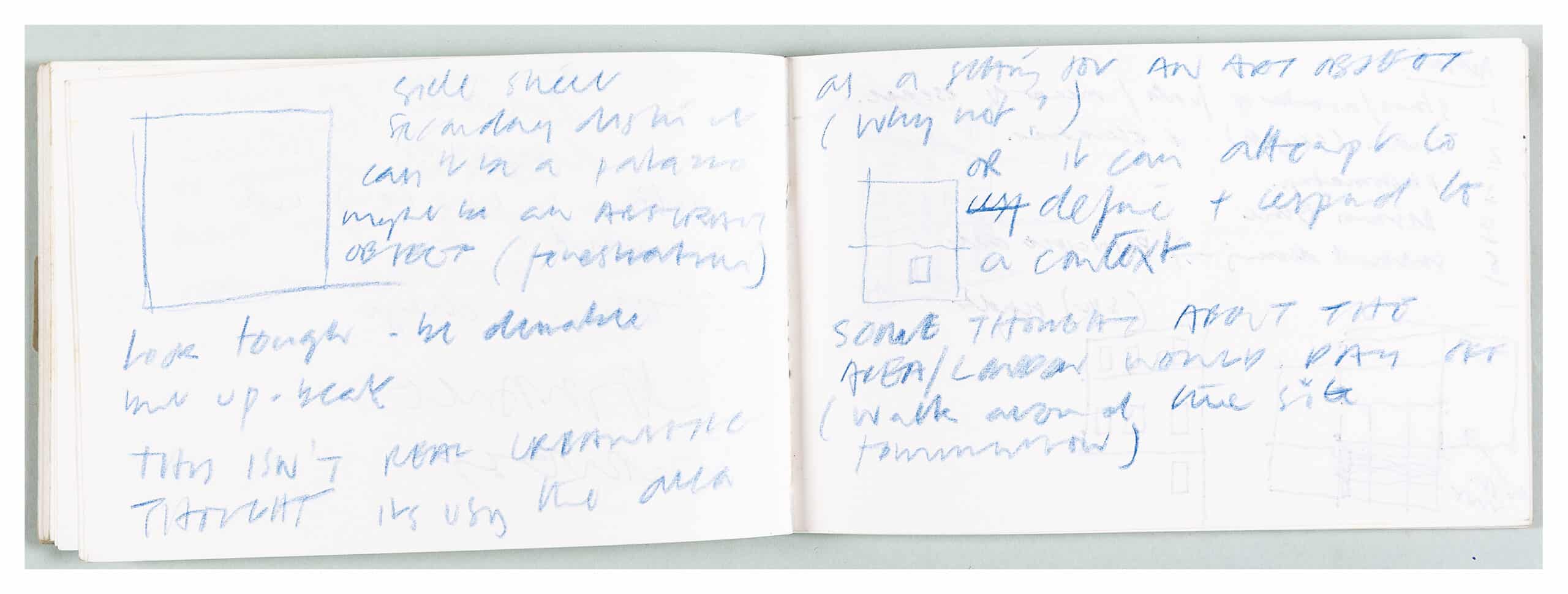

RAI: At the Drawing Matter collection, I found this sketchbook labelled ‘September 88-89, Early Lisson 2, Primary Decisions’. Among the many sketches, I found this text:

‘Side Street

Secondary distribution or district

Can’t be a palazzo. Maybe an abstract object [fenestration]

Look tough, be durable, but [up-beat?]

This isn’t real urbanistic thought; it’s using the area as setting for an art object [why not?]

Or it can attempt to use define and respond to a context.

Some thought about the area/London would pay off [walk around the site tomorrow]’

RAI: I believe this is the decisive moment for your Lisson Gallery 2 design. This not only addresses questions about using the area as an art object but also reflects your desire to stretch your proposal from the grounds of Bell Street into the London art scene. Would you agree with this assessment?

TF: Absolutely. I began to understand that this remote location was special, it wasn’t like the other gallery locations. I felt I could absorb some of the qualities in that area. I wrote that the building was out of the way, and it required a special journey to get to it. You walked through streets with particular geometric shapes, and then those shapes ended up being inside the first Lisson Gallery building, but rendered in the language of the art world, which was white minimalism, the white architecture of the art world. The shapes talk about the geometries of the neighbourhood, but the building talks about something else. In fact, you could say, I would say now, that it’s about the dichotomy of that building, of being a forward-looking and very successful art space in a marginal area.

RAI: The challenge posed by the second Lisson Gallery was one of connecting both ground-floor exhibition spaces. For that connection to be as smooth as possible, the avoidance of steps was imperative, resulting in an approximately one-metre drop from Bell Street to the ground-floor exhibition. In a very early stage, as previously discussed, you made the decision to propose a fully glazed façade for the two first floors of the gallery. This choice circumvented potential complications arising from windows views that could eventually end up disturbing or competing with the art displayed. From that decision, combined with your expressed desire to use the area as an art object, one can sense, that with a single simple gesture, you have decisively questioned all the then-established gallery concepts, elevating everyday street life and culture to art, placing the individual alongside the so-called erudite and educated world.

TF: That’s what I did. I have a talent for making objects which have meaning in them, which I am not aware of when I do it but is guided by the sensibility I developed through working on and reflecting on performance.

RAI: By fully glazing the first two floors, you have raised formal questions of weight, as if mass floated high above the ground. A similar contemporary project, the Sammlung Goetz Gallery by Herzog & de Meuron, completed in 1992, too has a similar strategy, delivering an illusion trick upon viewers by placing the mass in the centre and designing fully glazed façades on the ground and upper floors, making the central mass magically float in the air. Although it’s a brilliant building, from my point of view, your Lisson project poses more intriguing and relevant questions. Herzog & de Meuron’s building somehow is self-referenced and still in line with gallery conventions, while at Lisson’s, one senses the beautiful, deliberate, and quiet disruptiveness dignification of the everyday. I might be wrong but having in mind your interest in performance art alongside your very humane views towards society, you have deliberately decided to place the individual as well as its individual views above the norms by which society rules itself.

TF: I agree. While Switzerland has a very stable society, London is very stressed, with lots of different coexisting societal groups and cultures. I think I have absorbed that, and the Lisson is probably the most socially oriented gallery that you could ever get. I haven’t seen that building by Herzog & de Meuron, but I prefer doing what I did. I have produced an architecture of commentary. You can’t really define what the Lisson building is saying but you sense what it’s doing, and many people, architects and non-architects feel that. Buildings go out of date after 30 years, but the Lisson still holds people’s interest.

RAI: I first visited the Lisson Gallery in 1995. I believe both galleries were already connected, but I only seem to remember the second building.

TF: We had discussions with the artists about the relationship between the two buildings. Anish [Kapoor] and I felt that the two buildings could operate independently, Nicholas asked for a connection between the two for ease of management, and that connection has changed the way that visitors encounter the spaces, and the back gallery of the first gallery of the first building has lost its legibility. The lesson, which influenced my later buildings, is to recognise that change will happen and to facilitate it in ways that maintain the intelligence of the architecture.

RAI: Were you aware and conscious, that at some point, people would wonder if it is the street that opens towards the gallery or is it the gallery that opens towards the street?

TF: Well, that’s a question I can’t answer. I think that’s one legitimately for you to interpret. I think I always design with maximum ambiguity. A building, whether a gallery or some other type, should be open to interpretation by the people who encounter and occupy it. That has become been very important to me.

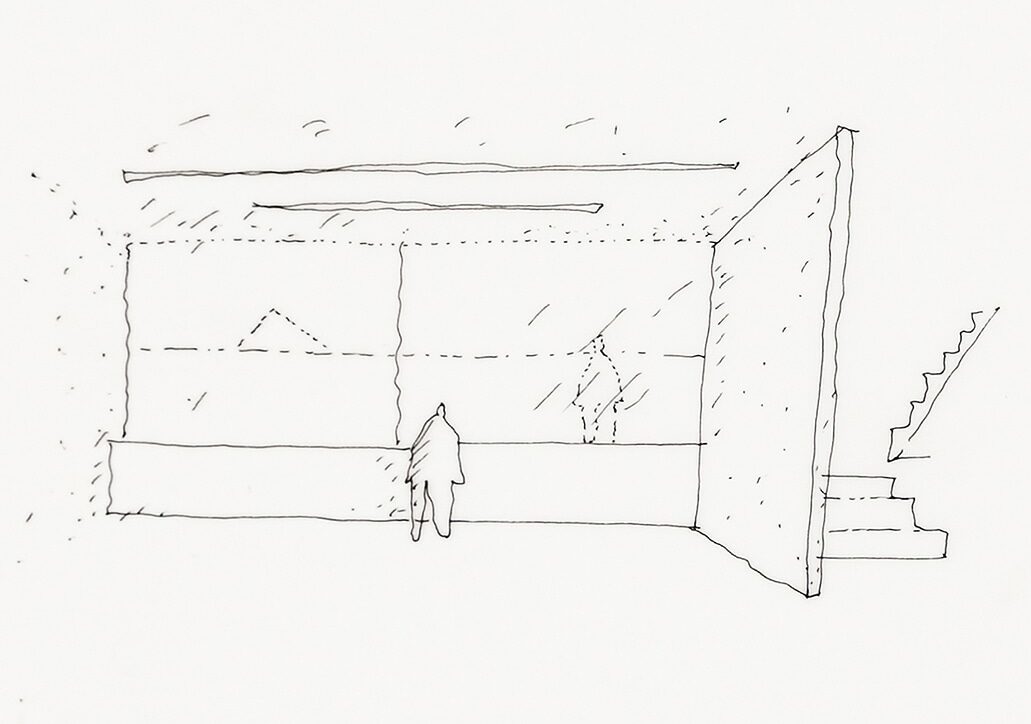

RAI: There’s this beautiful sketch that you produced from the inside of the gallery. Two individuals facing each other. One can feel the city in the foreground and no art is displayed, only human beings facing each other in an apparent harmony. This is a very powerful manifesto and having in mind that architecture, as art, takes more time to produce manifestos than all the other arts, one is tempted to affirm that this highlight of the margins and direct confrontation of the opposites, is your manifesto.

TF: It was very clear to me that the relationship with the district and not just the ground floor but the long view over the city was important. Why it was important, I didn’t fully know, but it has become clearer to me in the time since I designed the building. Design is an explosive state within the structure of ideas in your creative mind. The consequences of that, if the work is any good, are that you produce work that other people interpret, and enjoy. As you live longer, you look at what you have designed and understand more of what it is saying. Some of the things, I said immediately after I built the building remain true. When I’m designing, I don’t have a prospectus in mind. I deal with the matter of the project at the time and make artistic sense of it, stimulating interest in other people.

RAI: Twenty years later, you have again raised the question of the anonymous individual, on your project for the Fuglsang Museum in Denmark, where you created a room in which visitors can see the world outside the collection, where one is faced with the landscape shaped for centuries by anonymous working people. The worker and anonymous citizen are again part of your subject.

TF: Well, they are anonymous now, but they were not anonymous to themselves and their society. I am particularly interested in things that working people have made that are often disregarded. Especially in the art world, where only a Renoir matters, and then after that, there are fewer and fewer interesting people, and less and less value is placed on them. Just to continue this thought. I am Instagraming photographs, of everyday objects to show that they are interesting and were designed by somebody. Somebody decided is the form and colour of the bus shelter. Somebody in a state of exhaustion or inability made a very bad cement joint between two brick walls. Someone did all the things we see and use. At some level, all these things were made creatively. This thinking can lead to making an architecture that has compassion and social feeling.

RAI: Still, you propose an empty room in Fuglsang.

TF: The client group for Fuglsang was very creative and it was they that proposed an empty room. They worked on the brief, commissioning a local architect to show how the brief translated into a building, then they modified the brief again. They did all that before they put their competition brief out. Two things from the brief stand out: the room with no purpose, just to look at the landscape, and the other one was pocket spaces, where you have a tiny room where you have one picture. Magnificent thoughts. They’re not my thoughts; they’re the thoughts of a client that I have benefited from. Working with clients, it’s not always like this. There are very few clients who work with creative depth and who understand that buildings aren’t simply about representing them, but about commentary.

RAI: On his Royal Gold Medal Address on February 1st, 2018, Neave Brown said:

‘And then, when it all went off, when Margaret Thatcher completely stopped public housing, when she said there was no such thing as society, then I became an artist and in a curious way, I put it all way [architecture].’

Neave Brown stepped out of architecture when Thatcher came into power. You came into architecture when Thatcher came into power. You are both ferocious critics of the views of the Thatcher administration. Without Thatcher, without the social norms, without going against the established rules, one might need to reform his views. Isn’t it funny how our opponents bring the very best out of us?

TF: Creative actors with a social feeling, did not succumb to the sensibility of people like Thatcher. At the time, there was no investment in public space. I think it’s true to say, that the Lisson, in its way made a street outside it significant, I think that was stimulating for the younger generation that was growing up in Thatcher’s time, to see that whatever the function of a building it could have good social consequences.

Tony Fretton graduated from the Architectural Association and worked for various practices before setting up his architectural practice, Tony Fretton Architects, in 1982.

Ricardo Aboim Inglez is co-founder of Aboim Inglez Arquitectos, an architectural practice based in Lisbon, Portugal.