Roz Barr Architects: The Maquette

– Roz Barr

The act of making a physical artefact involves a to-and-fro engagement with an idea, in which decisions are ‘made’ and re-thought, and then un-made before the idea is realised.

This roundabout but essential process of adaption is carried out, in the work of my architectural practice, through the use of maquettes. My first response is often a sketch, but this quickly moves into a discussion about form through modelling, which informs material, spatial and formal decision-making. In making maquettes, the materiality of an initial concept can be made evident and then challenged through a synthesis of its content and context. By creating a three-dimensional response that explores its materiality the essence of the first idea is quickly arrived at.

It is a fluid process of thinking, with the model and the drawings being embodiments of the idea that is embedded at the beginning of the process.

The maquette is a means of manipulating the last act of thinking. Here we realise that a ‘project’ is an ongoing development in the subconscious, which evolves not as one idea but many.

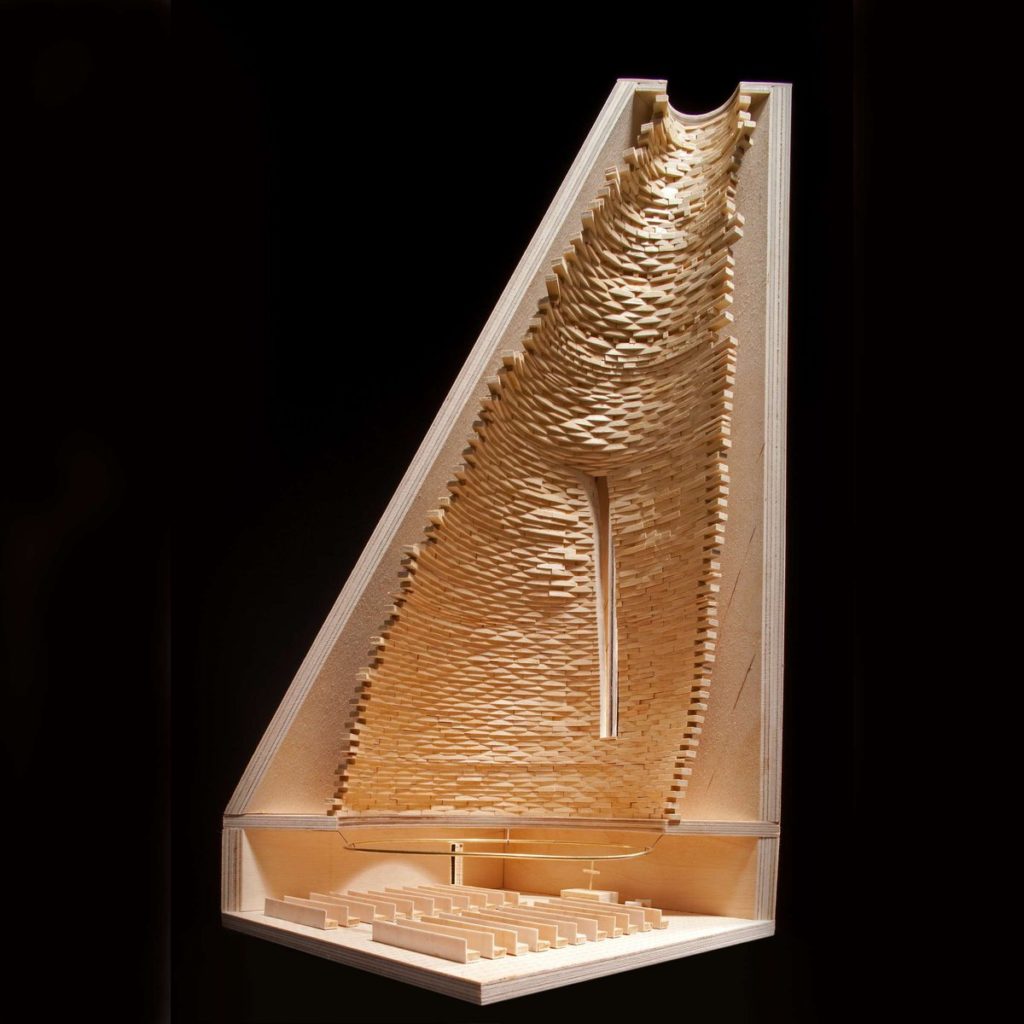

This is highlighted in the following projects, the earliest of which is a competition entry for a new church in Norway. The brief allowed the steeple to be 40 metres tall and set in very flat rural surroundings. The form we devised in response became a marker in the landscape and offered a shroud to a stacked timber block interior. This experimented with the materiality of the timber through the sizing and arrangement of the blocks. My first model was in paper and explored the form with a singular oculus at the top of the shroud. Once the form had been established we used smaller maquettes to explore the language of the skin of the shroud and the crafting of the internal sacred space. This modelling process evolved in tandem with the drawings, and this act of making also established the building process for the church proper.

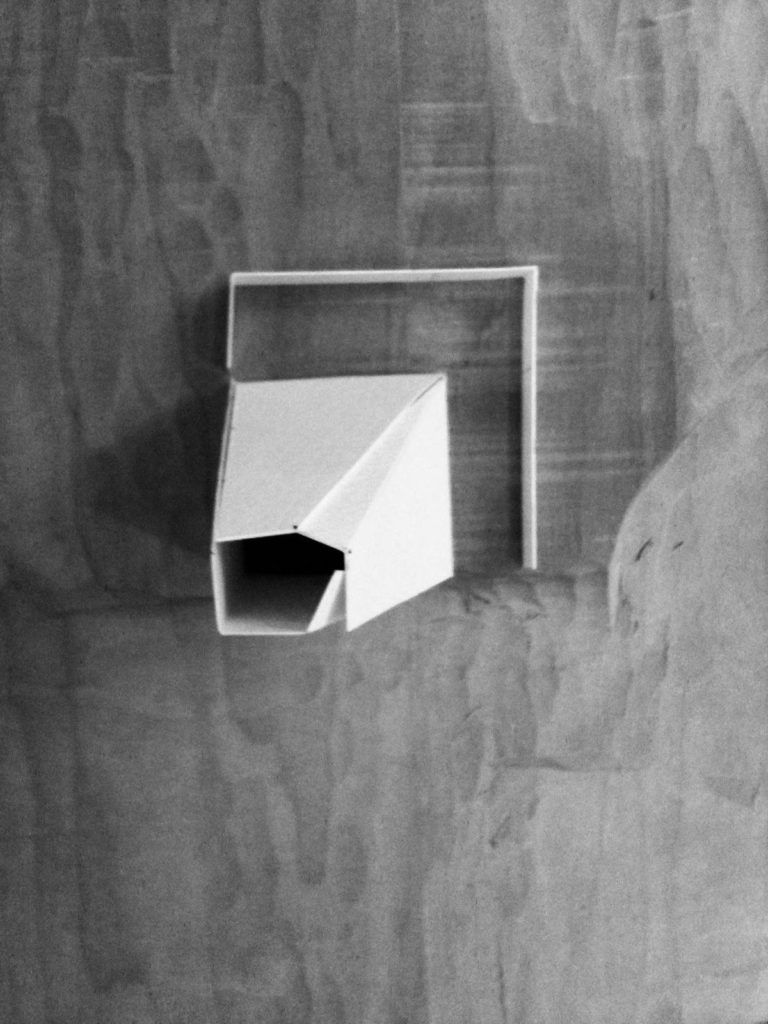

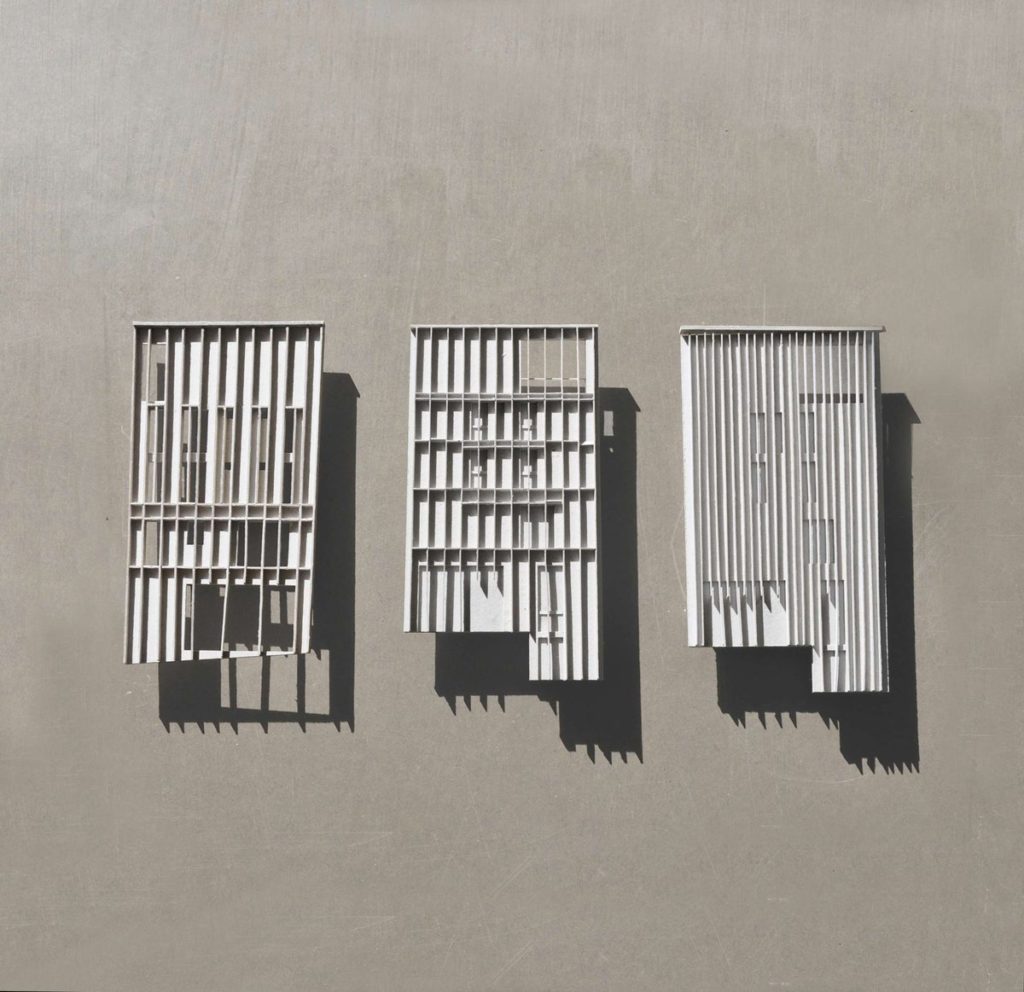

In 2012 a client sent me a photograph of a site in rural Scotland, which consisted of an existing steading next to the ruin of a medieval kirk. My visceral response to the photo was a tower. The monolithic form of the proposed tower was similar in scale and size to that of the steading building, and constructed in the same hand-set stones from the same site. The fenestration became a hindrance to the essential idea of the tower, since framing views from the inside seemed pointless, obsolete in relation to the constant presence of the surrounding landscape. This concept of suppressing the fenestration led to a series of cast maquettes, and the act of casting depicted the verticality of the stone coursing that we hoped to achieve. By casting into the plaster we could experiment with the position of openings, though my preference was always to have none.

This project in Scotland led to a commission to develop a new Augustinian Centre in a dense urban area of London. St Augustine of Hippo wrote of the ‘marker in the city’, the church being a room within the urban context. To elevate a new form that offered a tower to an existing context was an echo of what we had ‘unconsciously realised’ on the west coast of Scotland. Instead of stacking stone or timber, however, our cast of the monolithic form of the Scottish tower made the possibility of a cast tower here conceptually possible. In this instance it is cast in iron, in a return to the vertical emphasis of the heavy shroud of the church in Norway.