Ruskin: Fairy Tales

We all have a general and sufficient idea of imagination, and of its work with our hands and our hearts: we understand it, I suppose, as the imagining or picturing of new things in our thoughts; and we always show an involuntary respect for this power, wherever we can recognise it, acknowledging it to be a greater power than manipulation, or calculation, or observation, or any other human faculty. If we see an old woman spinning at the fireside, and distributing her thread dexterously from the distaff, we respect her for her manipulation. If we ask her how much she expects to make in a year, and she answers quickly, we respect her calculation. If she is watching at the same time that none of her grandchildren fall into the fire, we respect her for her observation. Yet for this she may be a commonplace old woman enough. But if she is all the time telling her grandchildren a fairy tale out of her head, we praise her for her imagination, and say, she must be a rather remarkable old woman.

Precisely in a like manner, if an architect does his working-drawing well, we praise him for his manipulation. If he keeps closely within his contract, we praise him for his arithmetic. If he looks well to the laying of his beams, so that nobody shall drop through the floor, we praise him for his observation. But he must, somehow, tell us a fairy tale out of his head beside all this, else we cannot praise him for his imagination nor speak of him as we did of the old woman, as being anyway out of the ordinary, a rather remarkable architect. It seemed to me, therefore, as if it might interest you tonight, if we were to consider together what fairy tales are, in and by architecture, to be told – what there is for you to do in this severe art of yours ‘out of your heads,’ as well as by your hands.

Perhaps the first idea which a young architect is apt to be allured by, as a head-problem in these experimental days, is its being incumbent upon him to invent a ‘new style’ worthy of modern civilisation in general, and of England in particular; a style worthy of our engine and telegraphs; as expansive as stream, as sparkling as electricity. But if there are any of my hearers who have been impressed with this sense of inventive duty, may I ask them, first, whether their plan is that every inventive architect amongst us shall invent a new style for himself and have a country set aside his new conceptions, or a province for his practice? Or, must every architect invent a little piece of the new style, and all put it together at last like a dissected map? And if so, when the new style is invented, what is to be done next? I will grant you this Eldorado of imagination – but can you have more than one Columbus? Or, if you sail in company, and divide the prize of your discovery and the honour thereof, who is to come after your clustered Columbuses? To what fortunate islands of style are your architectural descendants to sail, avaricious of new lands? When our desired style is invented, will not the best we can all do be simply to build in it? And cannot you now do that in styles that are known?

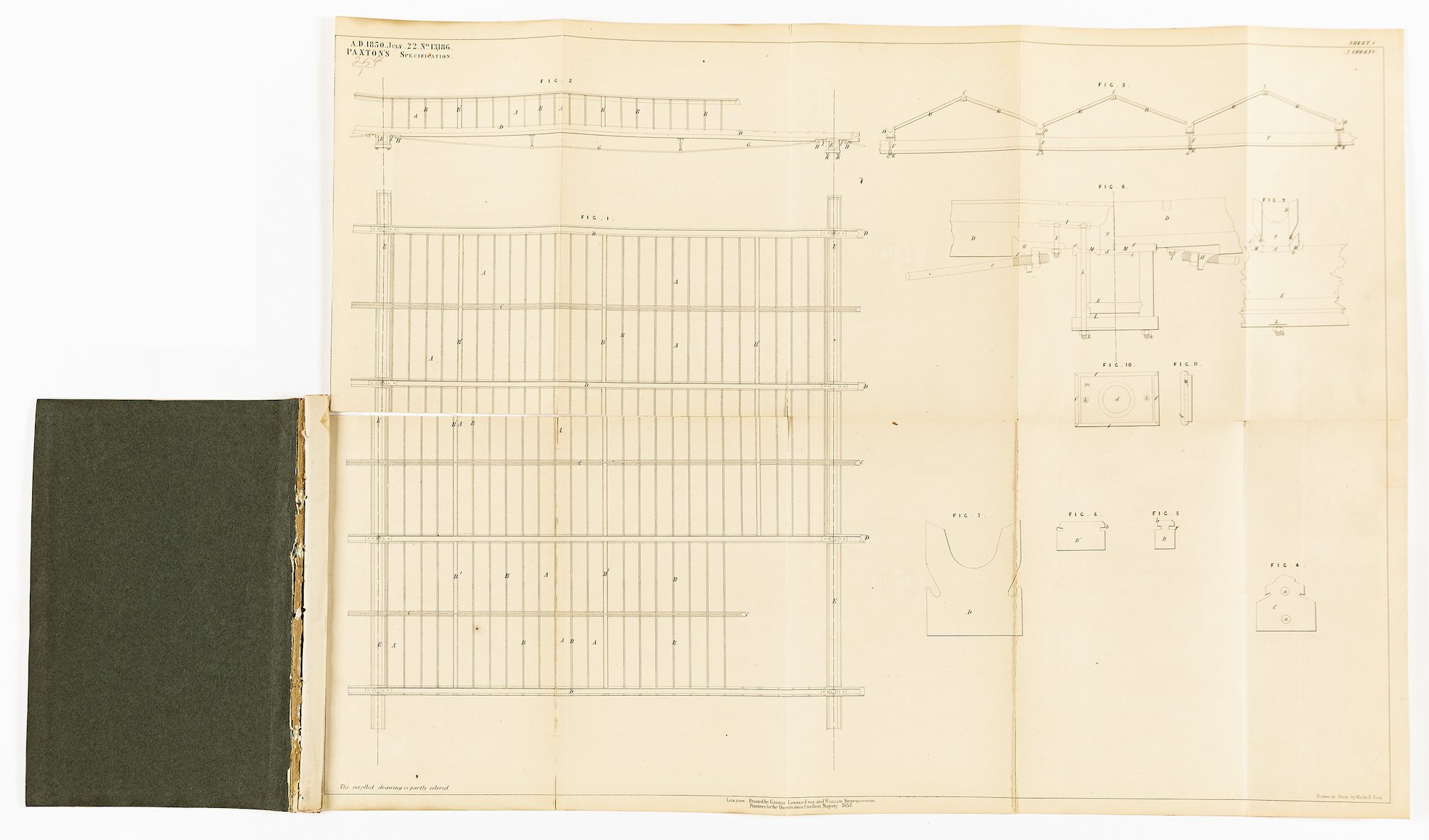

Observe, I grant you, for the sake of your argument, what perhaps many of you know that I would not grant otherwise, that a new style can be invented. I grant you not only this, but that it shall be wholly different from any that was ever practised before. We will suppose that capitals are to be at the bottom of pillars instead of at the top; that buttresses shall be on the tops of pinnacles instead of at the bottom; that you roof your apertures with stones which shall neither be arched nor horizontal; and that you compose your decoration of lines which shall neither be crooked nor straight. The furnace and the forge shall be at your service: you shall draw out your plates of glass and beat out your bars of iron until you have encompassed us all – if your style is of the practical kind – with endless perspective of black skeleton and blinding square – or if your style is to be of the ideal kind – you shall wreathe your streets with ductile leafage, and roof them with variegated crystal – you shall put, if you will, all London under one blazing dome of many colours that shall light the clouds round it with its flashing, as far as to the sea. And, still I ask you, what after this? Do you suppose those imaginations of yours will ever lie down there asleep beneath the shade of your iron leafage, or within the coloured light of your enchanted dome? Not so. Those souls, and fancies, and ambitions of yours, are wholly infinite; and, whatever, may be done by others, you will still want to do something for yourselves; if you cannot rest content with Palladio neither will you Paxton; all the metal and glass that ever were melted have not so much weight in them as will clog the wings of one human spirit’s ambition.

Excepted from ‘The Two Paths,’ an address delivered to members of the Architectural Association in 1859.

– Matt Page