Saul Steinberg: Bucharest, Milan, New York

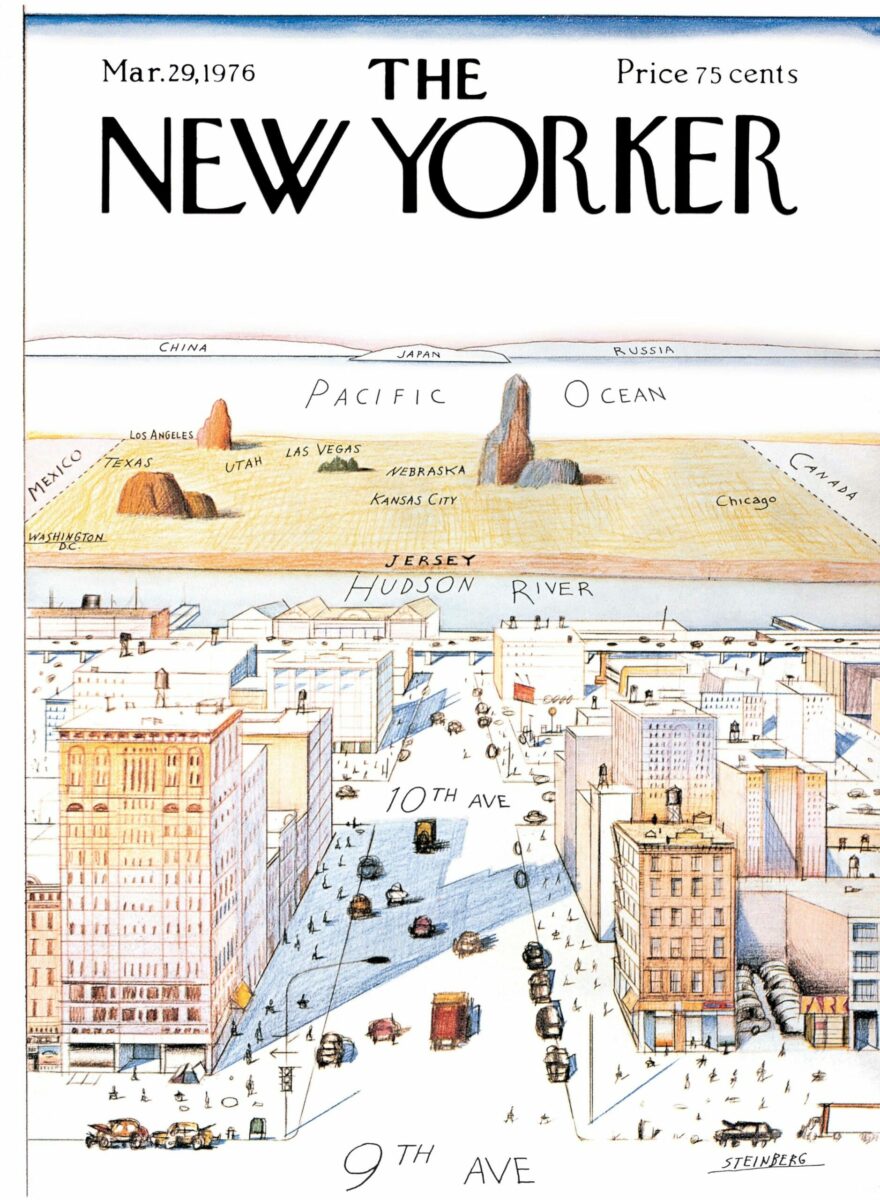

Steinberg is for me, first of all, the New Yorker magazine—one of the most intelligent and open American publications, with a very distinct graphic style that includes a generous use of drawings and cartoons, born and fed by the amazingly rich cultural landscape of New York City. I see New York as, first of all, the place that learnt like no other city how to embrace without inhibitions foreign people and cultures, and make them its own while letting them be themselves. This is the story of Saul Steinberg, born and raised in Râmnicu Sărat and Bucharest, educated in Milan, who survived fascism and war to bring his Eastern-European accent and irony to New York, and draw his trace there.

I don’t think it’s very relevant, but biographically speaking, I have many things in common with Steinberg. We belong, evidently, to very different generations and had very different life experiences. His native Romania is literally another country than my own, so fundamentally changed almost one hundred years after he left in 1933. If I do feel a personal connection to him, maybe it comes more from my records of my grandfather than from what I know of the real Steinberg. Still, we are both Romanian Jews. We are both architects. We both draw. We both have deep links to North America and to Italy. And indeed all this did give me a weird feeling, when I was looking at his drawings, pictures and documents; these few reflections are the most important ideas and feelings left in me, after having seen his works.

Drawing, not painting.

Steinberg found painting—as well as sculpture and writing—boring, or at least too rich, too complex, a ‘waste of time that avoids the essence of things.’ Drawing on the other hand was for him light, clear, essential—it transmits only and exactly what’s really important. Steinberg doesn’t only draw figures, spaces, objects, but has the courage to put on paper, and make clear and visible, abstract notions like words, conversations, even life pure and simple!

From a regular sketch to the next step.

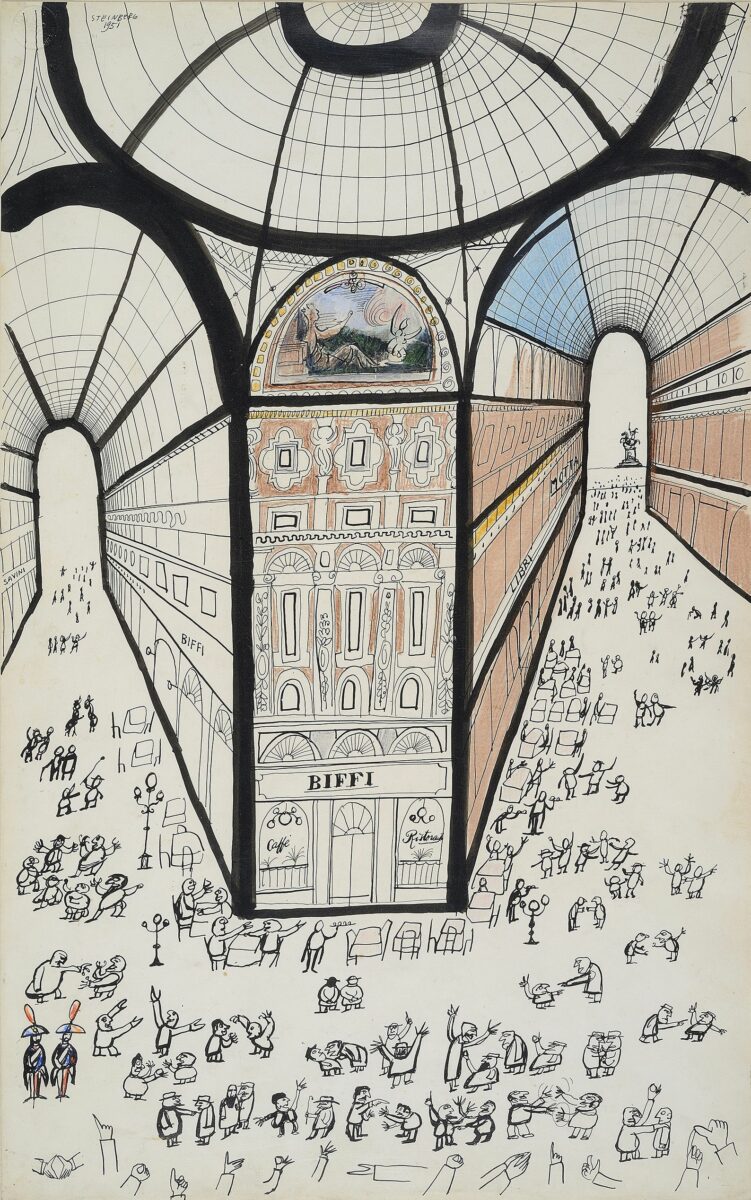

The exhibition (Saul Steinberg: Milano, New York at the 2022 Triennale di Milano) is full of sketches. Steinberg was reflecting reality through sketches in the very same way every architecture student still does today. Perspective, vanishing point… obviously he mastered them perfectly but all of a sudden, at a certain point in time, he stopped caring about them anymore! It is not that he forgot how to find the vanishing point. His drawing—like in his depiction of the iconic Galleria Vittorio Emanuele—has become so essential that it actually goes beyond perspective.

The Galleria—heart and soul of Milan—is for some reason, despite its complexity, a preferred subject for the sketches of my first-year students. Steinberg’s drawing of it is eerily similar precisely to the less complex, most primitive, childish of them all. It has only a few details, the perspective is approximate and the horizon line is way up at the fourth floor. At first sight it is anything but an ‘educated’ drawing. But if you look better you understand that Steinberg, simply, doesn’t consider important anymore where the horizon line is. His drawing is perfect. It represents exactly what one remembers from the Galleria, one or five, or twenty years after seeing it. The space, the crowds, are all there. Just please don’t tell all that to my students.

*

Stefan Davidovici is one of the founding architects of biroarchitetti and a lecturer at the Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti in Milan.

This article is extracted from a longer text originally written in 2022 for an exhibition of Saul Steinberg hosted by the Triennale di Milano. Find out more about the exhibition here.