Other Lives: Charles Eisen and Laugier’s Essai sur l’Architecture

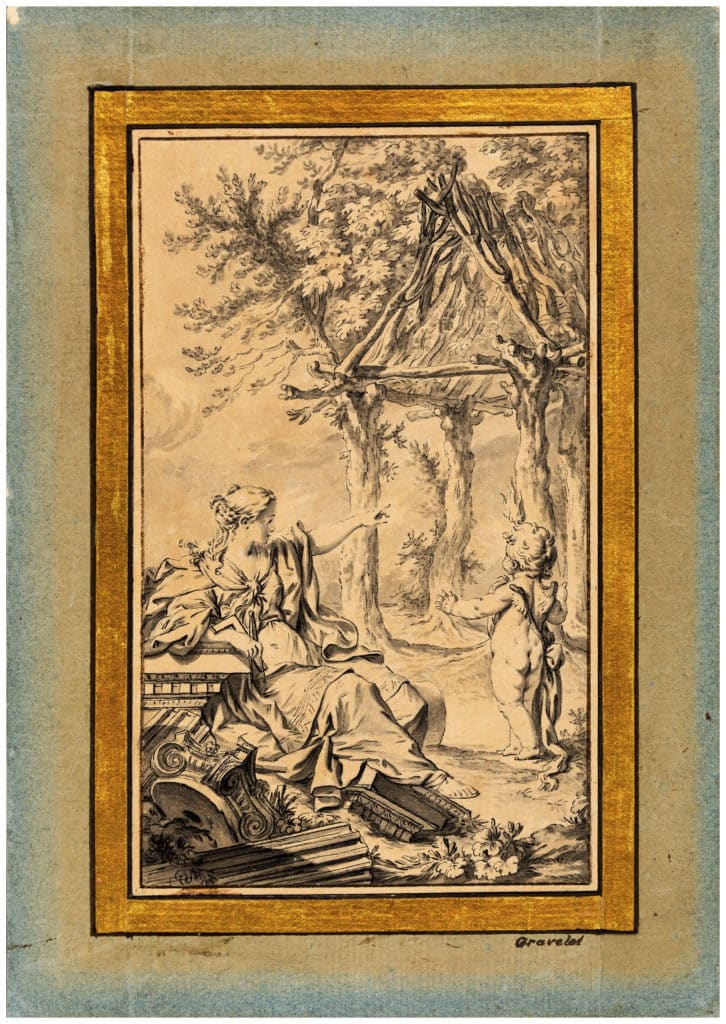

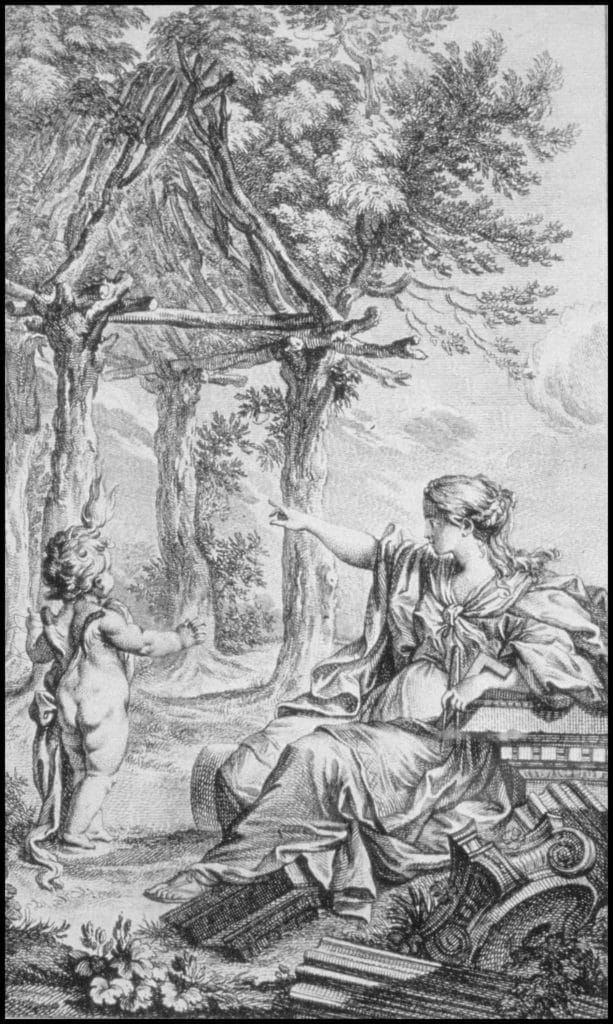

One of the best-known drawings related to the discipline is the ‘allegory of architecture’, drawn by Charles-Dominique-Joseph Eisen and engraved by Jean-Jacques Aliamet. [1] The original is now in the collection of Drawing Matter. Aliamet’s engraving serves as the frontispiece to the second edition of Marc-Antoine Laugier’s Essai sur l’architecture, and was included by the publisher after the success of the book’s first printing. [2] The image itself has had a life of its own, standing in for evocations of the primitive hut in reference to authors as varied as Vitruvius, Gottfried Semper and Le Corbusier.

The image alludes to a passage from Laugier’s text that describes ‘man in his primitive state’, a ‘savage’ seeking shelter and eventually making himself a dwelling by propping up four fallen branches vertically, laying others atop horizontally, and inclining yet more branches to meet at the highest point. Although not entirely faithful to this text, the engraving of Eisen’s drawing shows in the right foreground, a female figure – the personification of architecture – who rests upon building fragments, among them an Ionic capitol with the volutes turned to make four equal faces. In his text Laugier attributes this practice to the sixteenth-century architect Vincenzo Scamozzi, therefore making it a ‘modern’ artefact, rather than ancient relic. Across from Architecture stands a winged cherub, with plump buttocks and a pronounced cowlick in the shape of a flame. He gazes in a different direction than his companion, who points her finger towards four trees rooted into the ground. Nested among the branch stumps that protrude from the trunks of the trees are four branches lying horizontally. More branches incline, crossing over yet another that serves as a ridge beam.

The drawing is a departure from Laugier’s text. Eisen roots the trees into the ground and attends to connections and bracing, thereby resolving the structural defects in the original description. He further improvises by depicting the trees as grown in place. The neat square, comprising the same arboreal species and size, leaves unclear whether Nature or Man determined the arrangement. The architectural fragments indicate both past and future. Their ‘civilised’ forms represent a period subsequent to the primitive state of the tree structure, and yet, as ruins of an older culture, they represent a superseded past, with the gesture toward the tree structure indicating the future that Laugier is promoting.

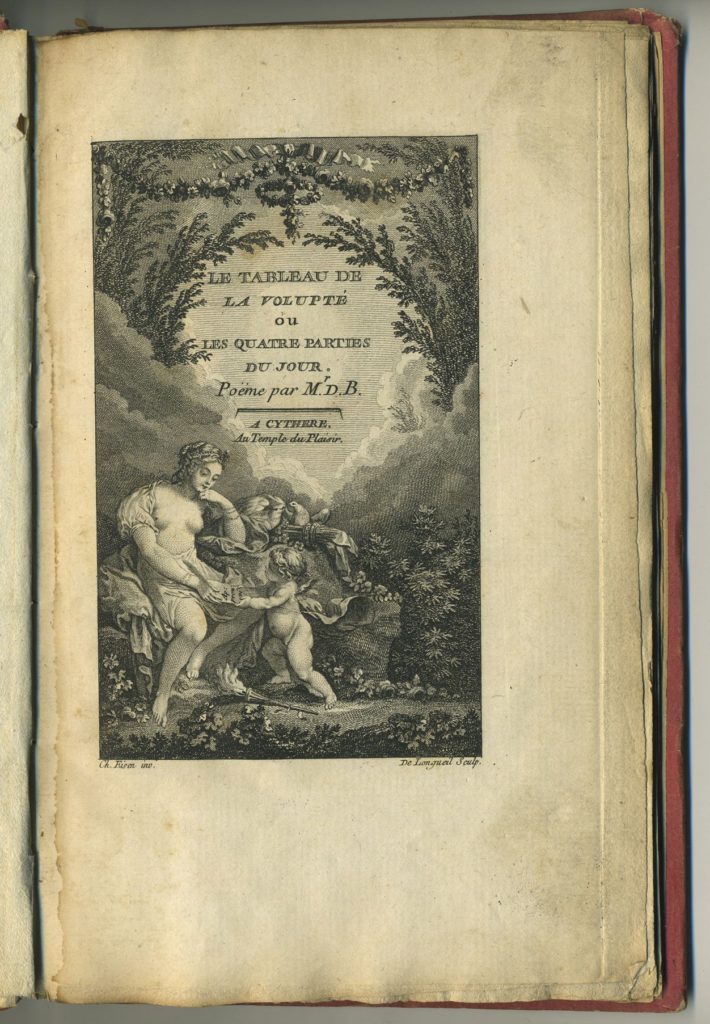

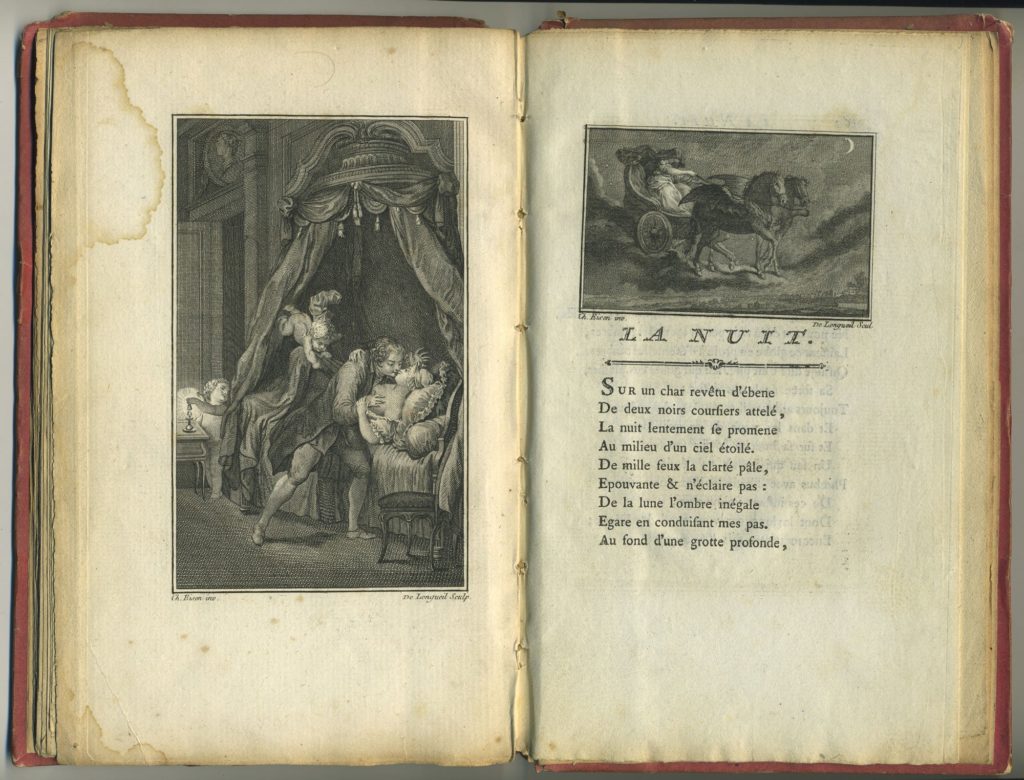

A reader viewing Laugier’s frontispiece at the time it appeared might have recognised the figures depicted and associated them with appearances in other contexts and, presumably, with their other adventures. By the time Laugier – or his publisher, Nicolas-Bonaventure Duchesne – selected the image for the frontispiece, Eisen had begun to establish himself as an artist of ‘voluptuous’ pictures for erotic and exotic books, branching out from the staid repertoire of Jacques Philippe Le Bas, in whose atelier he worked. [3] In many of these drawings, figures that appear to be the same lightly-clothed woman and nude boy in Laugier’s frontispiece cavort through all manner of mischievous and amorous adventures (a pair titled Les besoins d’amour shows the cherub relieving himself). Such drawings form the basis for illustrations of Gueudeville’s Eloge de la Folie (1751), a loose translation and augmentation of In Praise of Folly by Erasmus, Boccaccio’s Decameron (1757–61), La Fontaine’s Contes et Nouvelles en vers (1762), Ovid’s Metamorphosis (1767–71), Dorat’s Baisers (1770), and Montesqieu’s Temple de Gnide (1772). Shown here is Pierre-Ulric Du Buisson’s Le Tableau de la Volupté (1771). [4]

Given the contrast between Laugier’s strict and reductive notions of architecture and the implied licentiousness of Eisen’s imagery, the choice to commission this particular ‘allegory of architecture’ might at first seem unclear. Yet in his writing Laugier betrays a tumultuous emotional relationship with architecture, alternating between his desire to ‘penetrate her mysteries’ and his revulsion with things not being as he expected. Anxiety about cahos and lack of rules or guidelines animates his desires. But despite his self-admitted excitement at the idea of architecture, his writing about the discipline shows little intimacy with building processes and the decisions that inform and follow from them. It is also notable that the frontispiece provides little in the way of practical information about building construction, given that prior texts such as Claude Perrault’s Les Dix Livres d’Architecture de Vitruve did provide such guidance. Eisen himself depicted the construction site in another work, the image of La Folie des Bâtimens from Gueudeville’s Eloge de la Folie.

An early English translation of Laugier’s essai presents a different frontispiece, of men labouring on the construction of a building made of trees and branches. Architecture and her cherub are now replaced by a woman and child seated on a log, while other workers mix mortar and carry reeds in the foreground. But the scene is confounding since in the same book Laugier conveys his disdain for the construction site:

‘When one speaks of the art of building, the chaotic mess of clumsy debris, immense piles of shapeless materials, a dreadful noise of hammers, perilous scaffolding, a fearful grinding of machines and an army of dirty and mudcovered workman – all this comes to the mind of ordinary people, the unpleasant outer cover of an art whose intriguing mysteries, noticed by few people, excite the admiration of all those who penetrate them.’ [5]

The phrase ‘chaotic mess’ is consistent with Laugier’s rhetorical pitch, yet the original French of this passage is nearer to the older English translation, perhaps more closely rendered as a ‘confused mass of troublesome rubbish, a pile of shapeless materials.’ With these words Laugier promotes the superiority of the connaissance of the architectural critic over the savoir-faire of the builder. [6]

Laugier was certainly a connoisseur of architecture, as of music, painting, sculpture and other arts upon which he commented. He published two versions of the Essai, the first anonymously, the second augmented with his responses to critics, with a dictionary, and with plates tied to entries in the dictionary, not to the original text. [7] His critics do not dispute his status as a connoisseur, but they include him in the category of half-savant, as ‘… vain and decisive demi-sçavans… [who] set themselves up not only as judges, but also as legislators… the generality of their talents necessarily makes their connoissances superficial…’ [8]

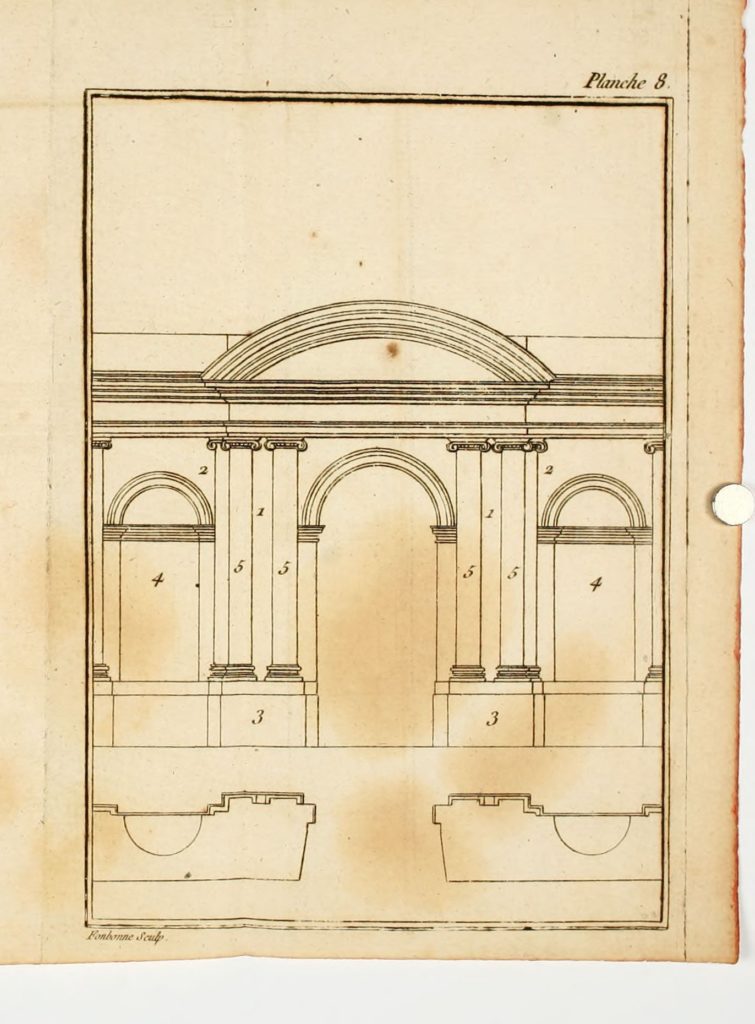

To illustrate his second edition, after having stated in the first that he would not show images, Laugier includes eight engravings by Anne Fonbonne. Her engravings show four examples of the orders on separate plates. A fifth plate shows four pediments, three of which, Laugier states in his text, are defective because they do not meet in a point. Three additional plates show compositions featuring pedestals and pilasters, also forbidden. The eighth and last plate combines three architectural transgressions – a curved pediment, pedestals, and pilasters – in the same composition.

The illustrations to his second edition and their engraver have enjoyed far less attention than Eisen and his frontispiece to Laugier’s text – today Fonbonne and her work as an engraver of architectural and figurative scenes seem to have been all but forgotten. On the other hand, despite the critiques of his contemporaries, Laugier’s words have endured through dramatic shifts in aesthetic preferences, building technologies and materials. The frontispiece, in turn, has enjoyed its own adventures, untethered to the constraints of the author’s argument.

Notes

- Michael Bryan, ‘Aliamet, Jean-Jacques’ and ‘Eisen, Charles Dominique Joseph’ in Graves, Robert Edmund, ed., Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, vol I (A–K), third edition, (London: George Bell & Sons, 1886), pp 18 and 459.

- Marc-Antoine Laugier, Essai sur l’Architecture, second edition, (Paris: Chez Duchesne, 1755).

- Jean Boccace, Le Decameron, Londres (Paris, chez Pierre Prault) 1757–1761.

- The author of the tableau, Pierre-Ulric Du Buisson (1746– 1794), was a historian of the American colonies as well as a playwright. He died by guillotine at the age of 48, having offended Robespierre. His Le tableau de la volupté, published anonymously under the initials ‘M D B’, is a slim and compact volume. The copy shown here is from the library of Viollet-le-Duc’s father and later owned by Carlos F MacDonald, celebrated ‘alienist’ and one of the inventors of the electric chair.

- Marc-Antoine Laugier, An Essay on Architecture, trans. Wolfgang and Annie Herman, p 7.

- Laugier and his contemporaries made a distinction between connaitre and savoir, both of which translate into English as ‘to know’ (a cognate of connaitre). While savoir accompanies a verb (knowing how to do something), connaitre accompanies a noun (knowing a thing, idea, or person). Connaissance is related to cognition; savoir to tasting.

- Between these two editions he participated in the Querelle des Bouffons (the Quarrel of the Buffoons), taking the side of the Coin du Roi, who argued for the merits of French music against the Coin de la Reine, led by Rousseau, who argued that Italian music was superior due to a language more adapted to emotional expression. After the second edition of the Essai, he wrote another book on architecture, the 1765 Observations, as well as books on other topics, notably one on the history of Venice and another on how to judge paintings.

- Anonymous (Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne), 1753.

– Mari Lending