Shape

Shape calls attention to things and their meanings. Architects, whether they mean to or not, give shape to things, and the people who see or inhabit those things, whether in full consciousness or not, respond to these shapes. The dimensions of this response are somewhat difficult to measure, since they consist of personal as well as more general components. Architects from the beginning have tried to compile systems and formulate rules of proportion and composition which would aid them in evoking responses from the people who saw the shapes they made.

The notion of grown people shaping things has been seen by many during the past half century as an act somewhere between the unfashionable and the illicit. Function, it was supposed, would give form a run for its money, and the less attention paid to shape the better. In the 1940s, for instance, a favourite drawing was of an absurd airplane, presumably designed by an architect. It was unable to fly under its deadweight of misunderstood talismen, columns, pediments, and walls of crumbling stone.

By the 1960s the arrogance of architects imposing a shape on things was under attack on social grounds, and form-givers (which means people who shape things) were labelled as cultural dinosaurs. The presumption was either that good things shouldn’t have any shape (in the same way a good society would not need any government) or that the shape of the environment would come, without midwifery, out of the interaction of users and makers. These presumptions, of course, were wrong. They foundered because function, by itself, is inadequate to define a single shape for a building. Since any functional problem can be solved by many different shapes, the choice is bound to depend on the preferences of the makers.

So we are still faced with the need to give things shape, and architects should note the nature of the guidelines there are.

One distinction provides help – that between shape and form. Form, as we have been told, follows function. It delimits an area in which things can take – that is, be given – shape. Spoons, for instance, are normally devices with a concave surface for holding liquids, with a handle attached to facilitate movement of the liquid and to provide protection for human hands in case the liquid is hot. There are billions of possible shapes a spoon can take, though there is only one form. The choice of shapes will be based on various cultural and personal standards. Or there is the interesting possibility that, for the task at hand, a spoon is not needed at all, and that a bowl or a siphon or a pump or a pipe will do the job better. Or there are cases in which the requirements of the form of the spoon have been violated, so that all the liquid leaks out, and no connections in the mind and memory, however poignant, can overcome the formal failure.

Of shape itself there are three measures: those that we all share (archetypal), we share with a culture (cultural), and those that are a product of our memories (personal).

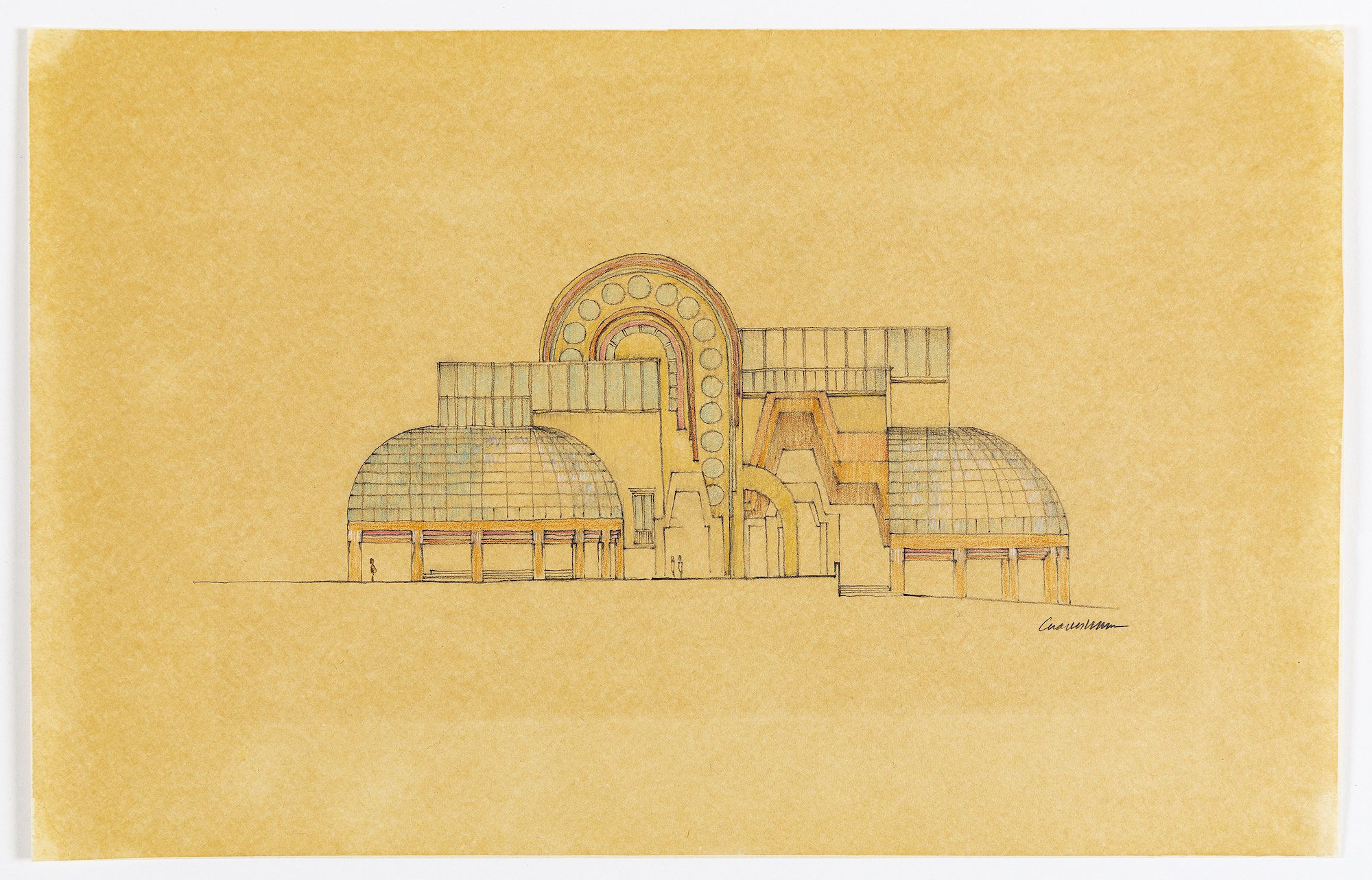

Archetypal shapes depend on an ancient dialectic between columns and walls. Since humankind came out of the caves, we have erected columns and spread out walls, and from an orchestration of those two acts we have developed the art of building. Our columns have consistently enough been taken as male fertility symbols, but they have an even more enduring role as celebrations of the uptight stance of humans. Our walls surely recall the cave, and the womb of the earth, but they exalt as well, by the ways in which they are arranged, the skill of the geometrician and the occasional triumph of reason. The plans of buildings and cities to this day are traces of columns and walls, and in civilisations from Philadelphia to Japan they still provide the basis for design.

Attempts to reach eternal harmonies through the proper relations of dimensions come close to being archetypal; at any rate they bridge many cultures. Andrea Palladio was interested in the relation of whole numbers, designing rooms so that the relation of the length to the width would be the same as the relation of width to height. The prevalence of the Golden Mean in the natural world and in the preferences of human beings has often been noted. The Golden Mean probably shows up most clearly in the Fibonacci series of numbers, where on a base of one and one, each succeeding number is the sum of the two previous numbers: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc. This relation, drawn as a series of squares, forms the basis for a spiral. The same spiral can be found in a snail’s shell, and it traces the creature’s growth. The same configuration was also long ago appropriated for the volutes of the capital of an Ionic column. Even now, people, when tested, seem to show a strong preference for rectangles in the proportion of any two succeeding numbers in the Fibonacci series past the first two. The possibility of growth, one takes it, is discernible in the shape, and that presumably explains its appeal.

Some preferences for shape are cultural. Gothic builders were excited by vertiality. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the preference which was developed in their soaring cathedrals extended also to pointed windows on houses and pointed tops on boxes and chairbacks. No surprise, either, that it was taken over whole by nineteenth century romantics, who were able to read moral rectitude and spiritual enlightenment into the verticality of pointed architecture, and only worldliness into more horizontal shapes. Esthetic tilts between Gothic and Classical styles grew astonishingly vicious. But if we start to feel at all superior because of our distance from these horrid little wars of taste, we need only note the fervor with which contemporary clients state their preferences for materials; the choice of natural wood or white walls has become a kind of Rubicon of architectural decision.

Cultural preferences for one shape over another slope quite quickly into personal preferences, based partly on what we have been taught, but mostly on our memories. The sound of an outboard motor across a lake may be for some people less likely to stir up concerns about the energy crisis than to recall a carefree childhood summer. And several patterns of mullions which may divide the same window opening might have connotations – dimensions – very different from each other, depending on the connotations they have in our own experience, the places loved or scorned out of our own pasts.

So, in the end, what is the architect to do in the face of the endless diversity of human experience, the presence of personal as well as cultural and archetypal components to our perceptions of shapes? One useful part of the response is to render unto the mind’s eye what is the mind’s eye’s, but to take care that the images do not interfere with flexibility of human use – the chance to massage our sensibilities with shapes that are likely to be familiar to us (whatever their specific connotation to our individual lives) and shapes or relationships full of surprise, which call us to attention and response, readying us for choice.

Excerpted from Charles Moore, Dimensions: Space, Shape & Scale in Architecture (1977)