Sixty Metres, Sixty Degrees

This text is loosely based on the first part of my lecture ‘The Landscape Model,’ delivered at the Sverre Fehn-designed Hedmark Museum in October 2023. The lecture was part of the Sverre Fehn Symposium ‘Authoring Architecture in Time’ organised by AHO and the Hedmark Museum, and curated by Professor Mari Lending. [1]

The names of minerals and the minerals themselves do not differ from each other, because at the bottom of both the material and the print is the beginning of an abysmal number of fissures. Words and rocks contain a language that follows a syntax of splits and ruptures. Look at any word long enough and you will see it open up into a series of faults, into a terrain of particles each containing its own void.[2]

One of the many reasons not everything built or drawn is architecture is that, at its best, architecture is also code—a language that transcends the act and fact of building, as well as the act of modelling buildings or writing about them. By code, I do not mean gospel, dogma, or tradition—let alone typology. There is nothing esoteric about it. Effective code emerges when a building, a designed landscape, or even a fragment of either becomes so lucid in a singular drawing that it communicates itself as a symbol, an image, and a scalable physical space all at once. Architecture, then, is space as language, complete with its own syntax. Its genes can and must be contained in a single drawing: a fragile yet lucid chromosome. The most enduring precedents of this type of code are elastic, their scale plastic, agnostic of site, climate, local culture, and sometimes, even construction methods.

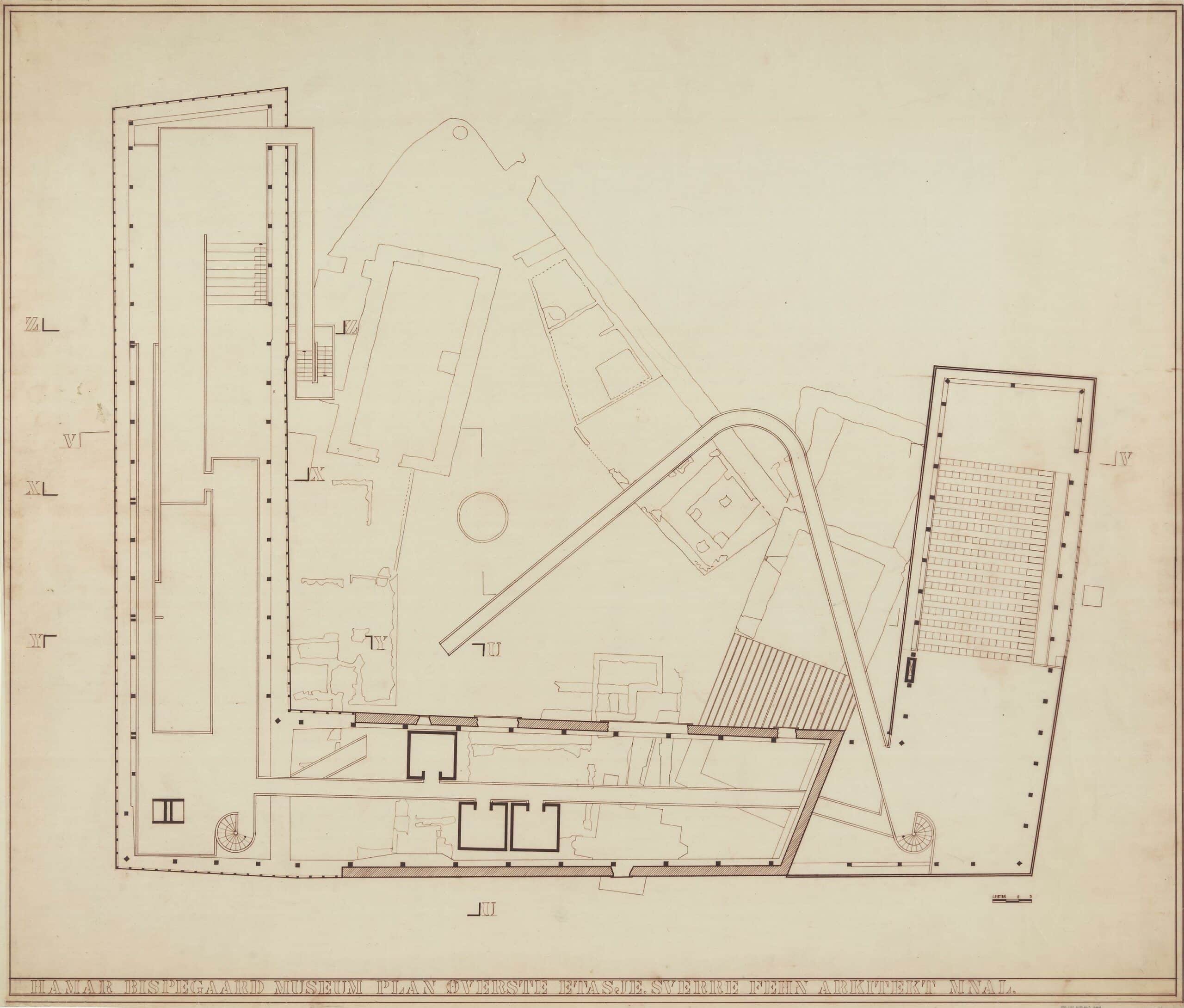

My first encounter with Sverre Fehn was in 2001 as a first-year architecture student in Colombia. Or, to frame it differently, my first encounter with Norway itself—and Fehn as an author—was through a plan of the Hedmark Museum at Domkirkeodden in the book Sverre Fehn: Opera Completa (1997). Back then, someone told me it was a favourite of Rogelio Salmona, who had recently passed away. To this day, the book is on Salmona’s desk.[3]

At the time, I knew nothing of Norway, let alone Sverre Fehn. But the plan of Hedmark introduced itself to me as pure code. Why code, and not just precedent or case? It is simple. Those days, we were collecting and studying Le Corbusier’s plan drawings of ambiguous interior/exterior ramps—those where it is hard to pinpoint entrance doors in plan. At the same time, the work of Enric Miralles & Carme Pinós was everywhere in the early 2000s and was presented to us as one of the few architects able to run rings with Corbusier in his own promenade game. The radical idea that scale is plastic, was understood at that same moment through Miralles’ and Pinós’ geometric triangulation studies, where the same form could be tested at different scales and even different projections. When I found Fehn’s drawing in our library, I thought: it’s not just the Catalonians. This Norwegian man knows how to run rings around Corb, too—and perhaps more effortlessly.

Fehn’s ramp—or, more precisely, his code or equation for a ramp—is elastic. Not in the material sense of course, but as a gesture that connects different spaces while linking disparate historical moments. A singular drawing, along with a glance at Hélène Binet’s photographs of the space, also sparked our interest in this sort of archaeological project, where ancient architecture becomes landscape, turning into architecture again via assertive gestures, such as this ramp.

The drawing of the ramp made the ruins in a country I had never visited apparent, but more importantly, it also made them interesting. The lines crossing through imagined space made us think about the vertical extrusion of that which is cut in plan but is not there any longer. In other words, the violent but surgical operation of the ramp—for which I later learned Fehn was criticised in Norway—compelled those of us with little knowledge of the place to see these foreign ruins in space.

The ramp spans sixty meters in length and forms a sixty-degree angle, addressing an elevation difference of several meters. A beautiful ramp that does not just serve as functional circulation taking us over ruins; its deeper merit is that in a stroke, it debunks the myth that Nordic architecture can not escape the tyranny of thermal barriers. For me, as a young student, Fehn’s code made Corb’s ramp at the Carpenter Center look cute at best.

For code to transcend precedent or type, it must simultaneously integrate and reveal the fragments of code it supersedes. Or, to put it a different way, a fragment like this ramp is a chromosome—transparent and fertile in its potential for hybridization. Without the need for accompanying discourse or cultural references, the drawn code must also demonstrate, on the spot, the evolution of prior codes—in this case, that of Le Corbusier’s taxonomy of ramps.

Fast forward seven years. That ramp persisted in our minds throughout our studies in architecture school, surviving contact with teachers, new references and trends. It proved that drawn code resists that sort of friction. In 2008, when I was building my first public project—the aquatic facilities and pools for the South American Games in Medellín—we summoned Fehn’s ramp code as an equation. Our project’s construction site, with its excavated swimming pools, looked like an archaeological camp—a construction site with elevation differences similar to Hedmark. Though we still knew next to nothing about Fehn, his body of work, or Norway (where I now live and work), we decided that in our horizontal composition of pools, the only elements not straight—those allowed to curve while rising above the ground—would directly reference Hedmark. Or, to be more precise, not Hedmark the place, the total project, nor Fehn the author, but the pure code I remembered from the plan of the ramp found in the architecture school’s library.[4]

Notes

- Today, I teach at AHO. The same school as Fehn did. It is interesting to discuss now how a drawing, carrying its code, travelled far back then—from 60° North to 6° tropical latitude. My colleagues in Oslo can certainly speak in a more precise and eloquent way about Fehn’s work, however, these days, I find it important to talk about how an architect’s influence can travel in time and space via the dissemination of a few drawings alone devoid of discourse. This influence was certainly agnostic to the problematisation of authorship, the contingencies of practice, phenomenological descriptions of space, or the personal stories that recently seem to affect Sverre Fehn’s work reception in Norway.

- Robert Smithson, ‘A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects’, Artforum, September 1968.

- Rogelio Salmona never visited the Hedmark museum.

- I visited the Hedmark Museum for the first time six years after completing the aquatic centre in Medellín, reiterating the absolute trust we had in the code of a building we had never visited before.

Luis Callejas is an architect and founder of Oslo-based LCLA OFFICE. Callejas is also a professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and visiting professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (2024-2026). His completed works include the landscape for the renovation of the former US embassy in Oslo designed by Eero Saarinen, the aquatic centre for the South American games, and the renovation of Bogotá’s national stadium. He is the author of the books Houses in Forest Clearings and Pamphlet Architecture 33: Islands and Atolls, among others.