Sydney’s Infill Facades

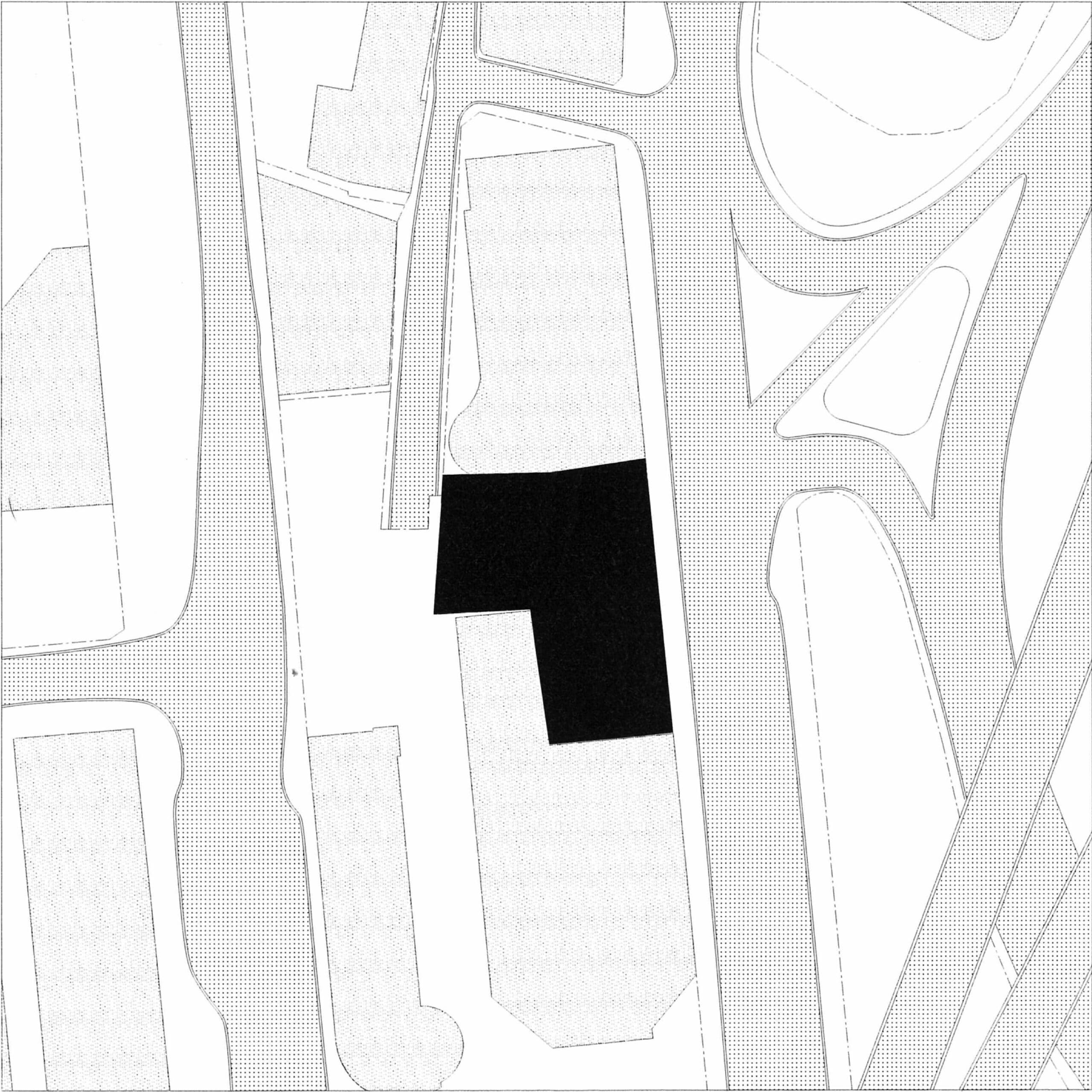

This survey intends to draw and identify the material and facade arrangements of office buildings in Sydney. Built between 1950 and 1980, the selected buildings are examples of a certain type of post-World War II city infill fabric, characterised by their 4 to 16-storey building heights, shared party walls, fine-grain street frontages, and absence of setbacks. Developed amidst the turbulence of the Central Building District’s mid-century building boom, facilitated by loosening legislations on development controls, these buildings quickly replaced much of the city’s 19th-century architecture. Alongside their contemporaries such as the work of Peddle Thorp, Walker’s AMP Building, or Rudder Littlemore & Rudder’s Qantas House, these infill buildings are categorised within Sydney’s Modern Movement. Whilst they are attached to this period, their seemingly unremarkable facades are unprotected by heritage legislation and award them a precarious role in the city.

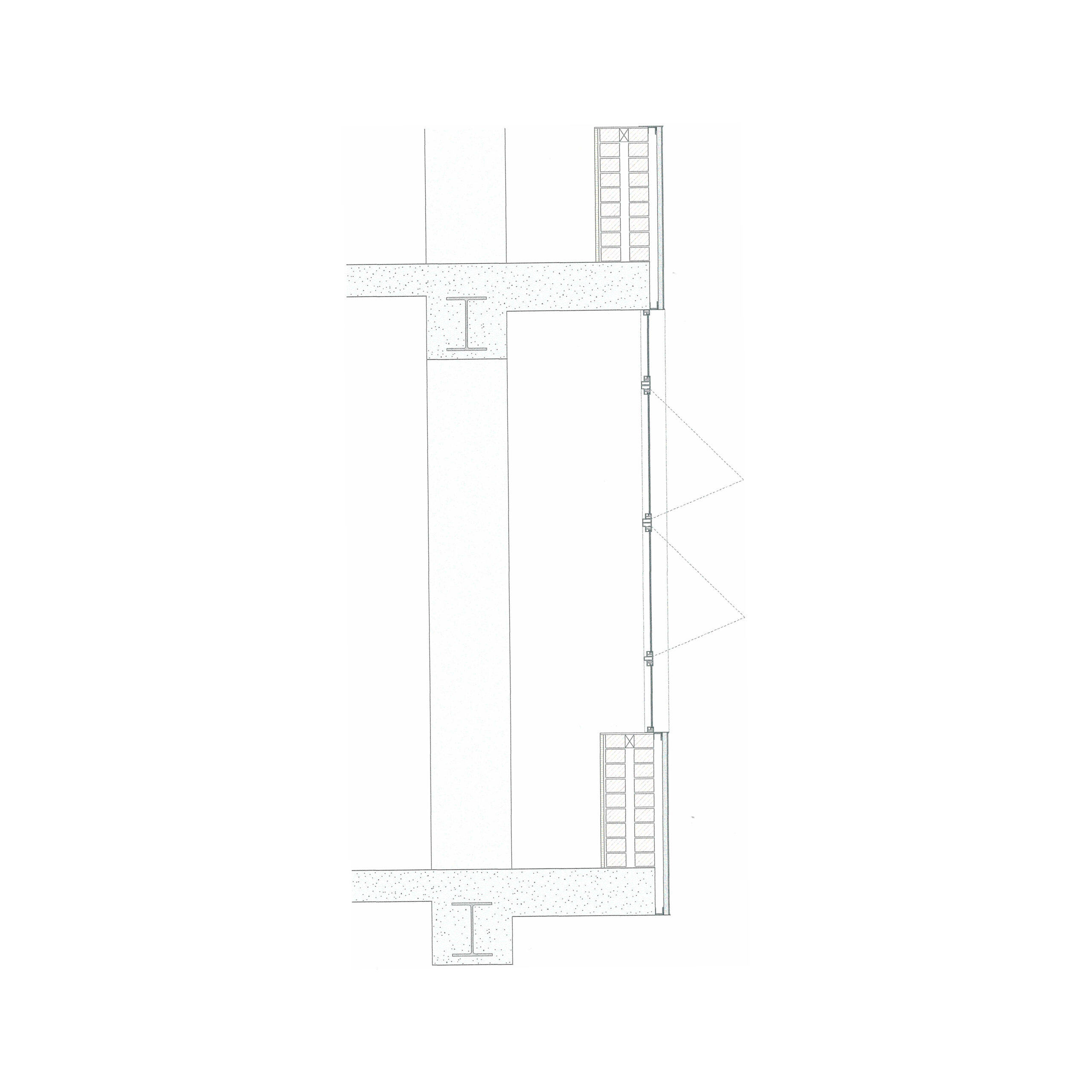

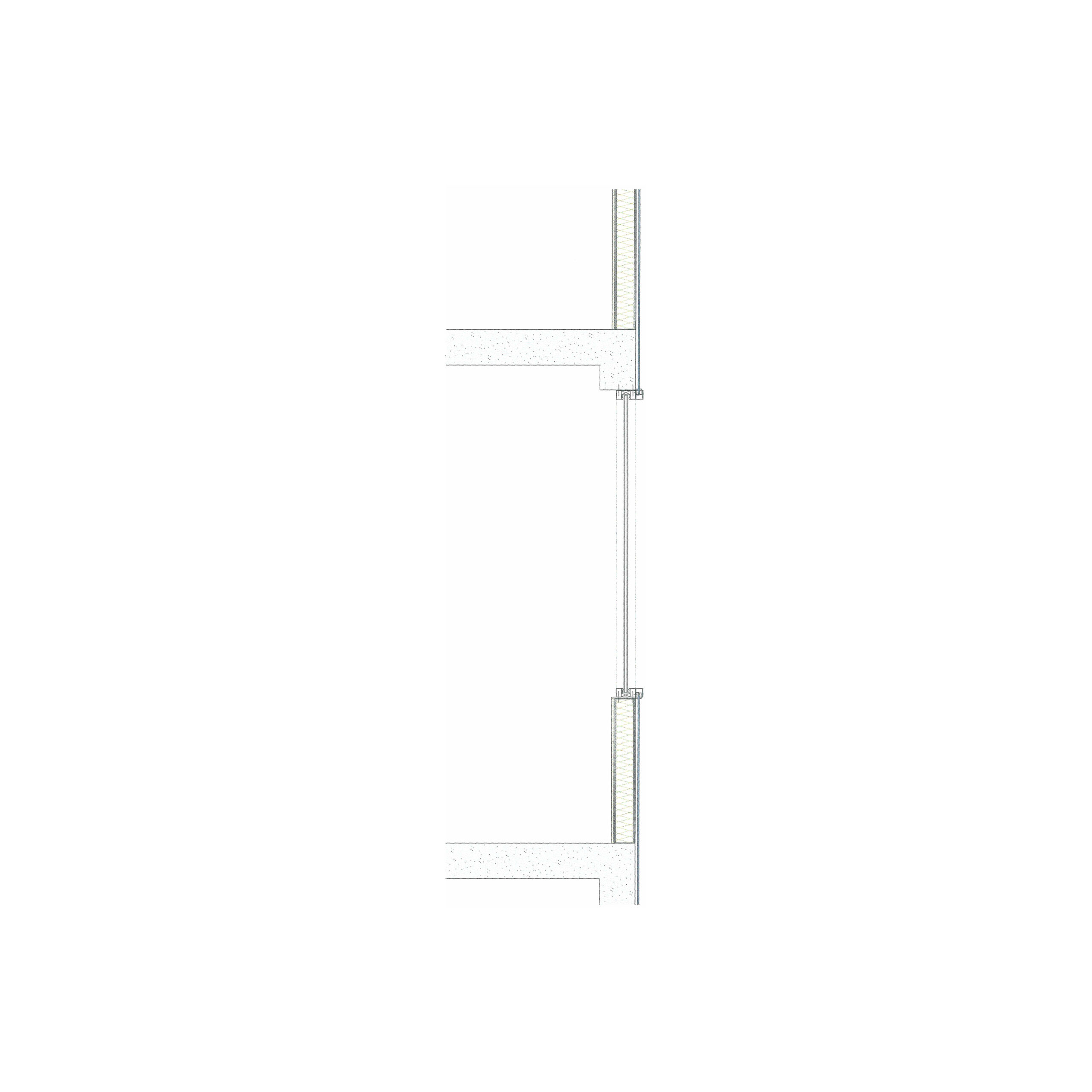

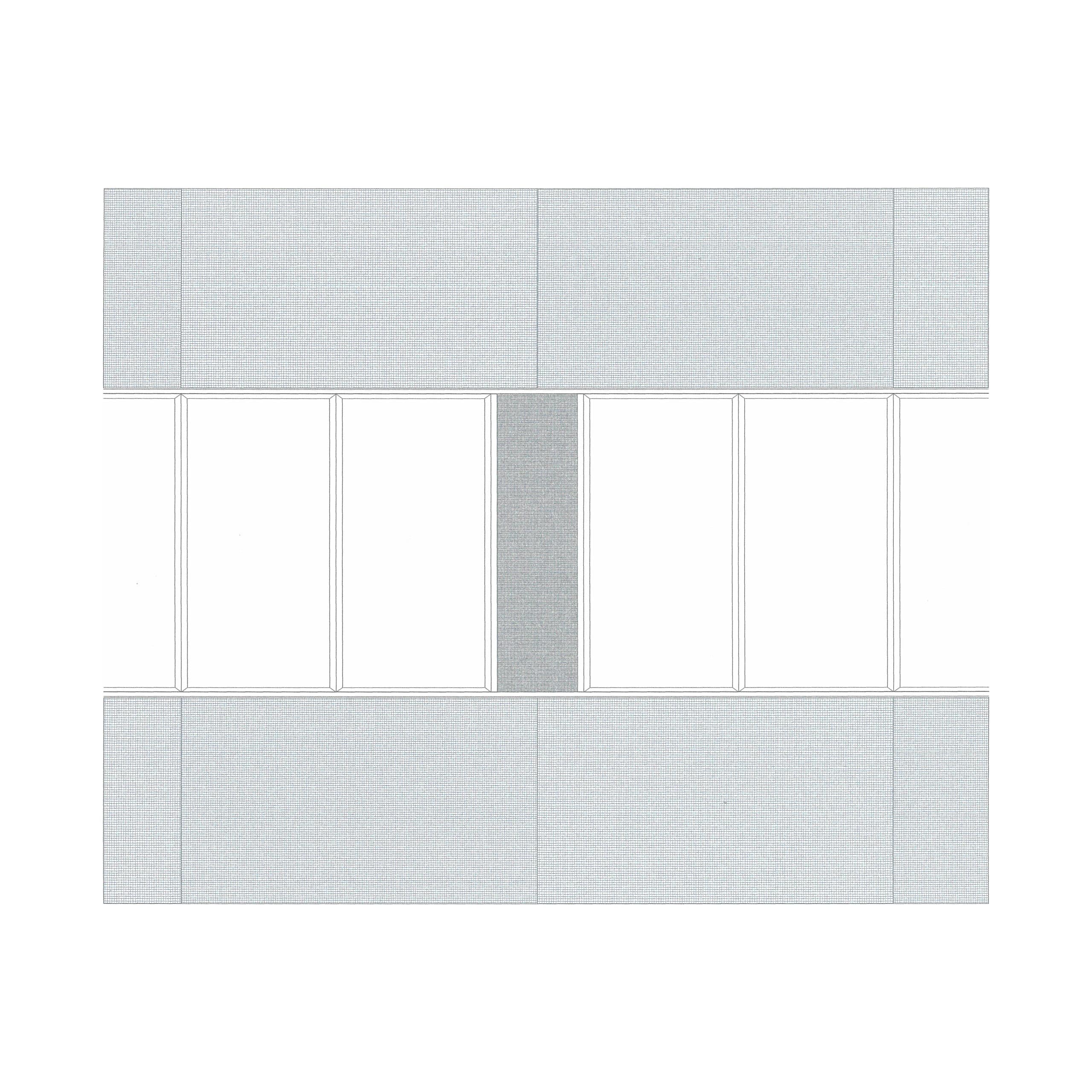

Sydney Central Building District’s infill buildings are not an uncommon architecture. Their similar facades are made up almost all from commercial architectures of the time—using the same catalogue of globally available aluminium glazing systems. The local adornment these systems were paired with—a suburban tiled rustication, stonework facing, or a corrugated metal spandrel—provided an indication of context whilst the construction materials used hinted at the economy of the work. A clear legibility of materials made their construction obvious—we can understand that the glazed window module sits on an infill wall, clad in tiles, atop a concrete slab with an exposed edge, eventually resting on shear brick walls. We find this building type gains relevance at larger scales, with its facade construction based on a basic kit of parts, it freed the architect to engage with the ornamentation and proportion of the structure. Today, these infill buildings and their facades remain as artefacts of this period, documenting the negotiation between construction catalogues and architect’s ornamentation.

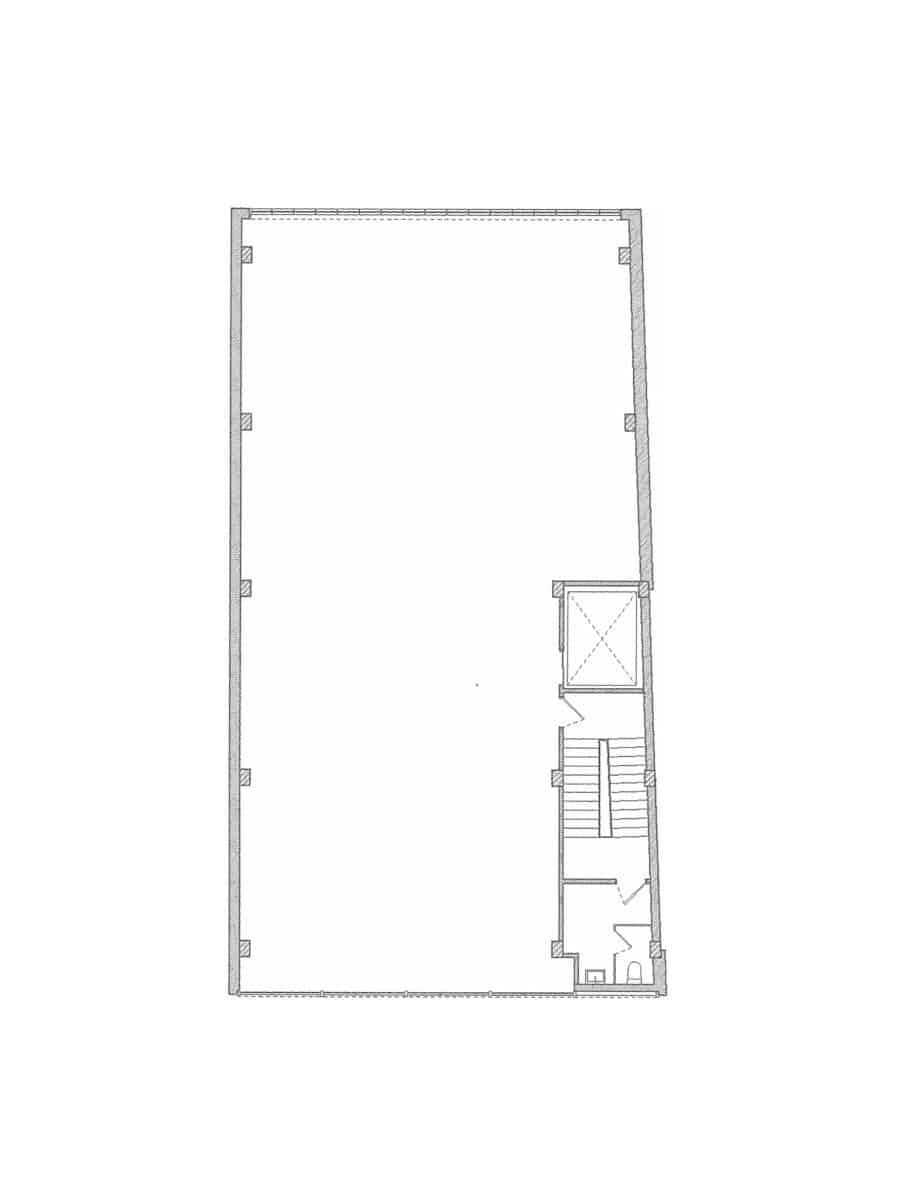

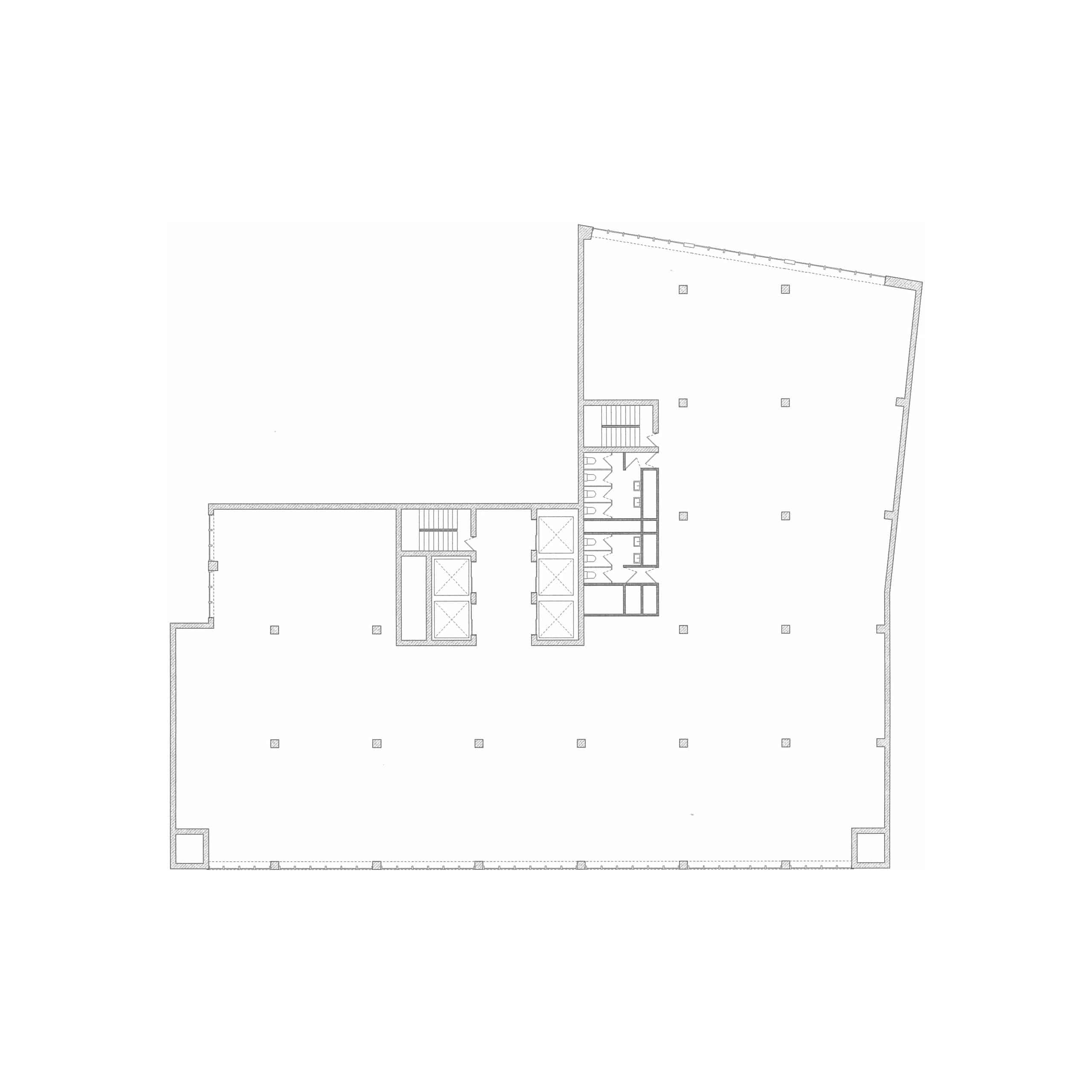

Beyond their facades and materials, infill buildings utilised a pragmatic and ruthlessly generic plan that, give or take a chamfered or notched corner, trace exactly their lot boundary. The absence of the offset presented the building directly to pedestrians, with its fine grain fabric creating diverse retail street life. On floors above, plans were almost identical at each level. Cores efficiently contained services and circulation, often with bathrooms of male and female genders alternating on each floor. The rest of the plan was left open, populated by structural columns. For the wider infill lots these columns allowed for the messy occupation of partition walls which regularly transformed floor plates to tenant requirements. Often nestled within two shear party walls (corner lots an exception) the plan let light in primarily from its horizontally banded glazed front facade. Its rear facade, whether facing a road or a light well, held smaller windows, direct fenestrations in its brick or blockwork walls. Infill buildings required no correlation between plan and facade and were easily adapted—seeing many alterations, additions, and facade renewals over time.

This is a survey of infill office buildings in Sydney’s Central Building District—none of which are examples of an exemplary architecture, but one that is simply good enough. Having dealt with the complexity of standardised construction methods, yet still able to allude to a certain material culture and ultimately the specificity of Sydney as a city—these buildings attempt to demonstrate the appreciation of architecture as background.

In order to understand how to build in Sydney, we need to understand how the city was built. Drawn somewhere between how they once were and how they are now, without services, and focused on material, these buildings, and their elevations, plans and details, represent the beginning of a survey of the city, its infill facades, and more importantly, how they are put together.

The survey looked at 9 sites across Sydney. The following three case studies are extracts from this larger body of work.

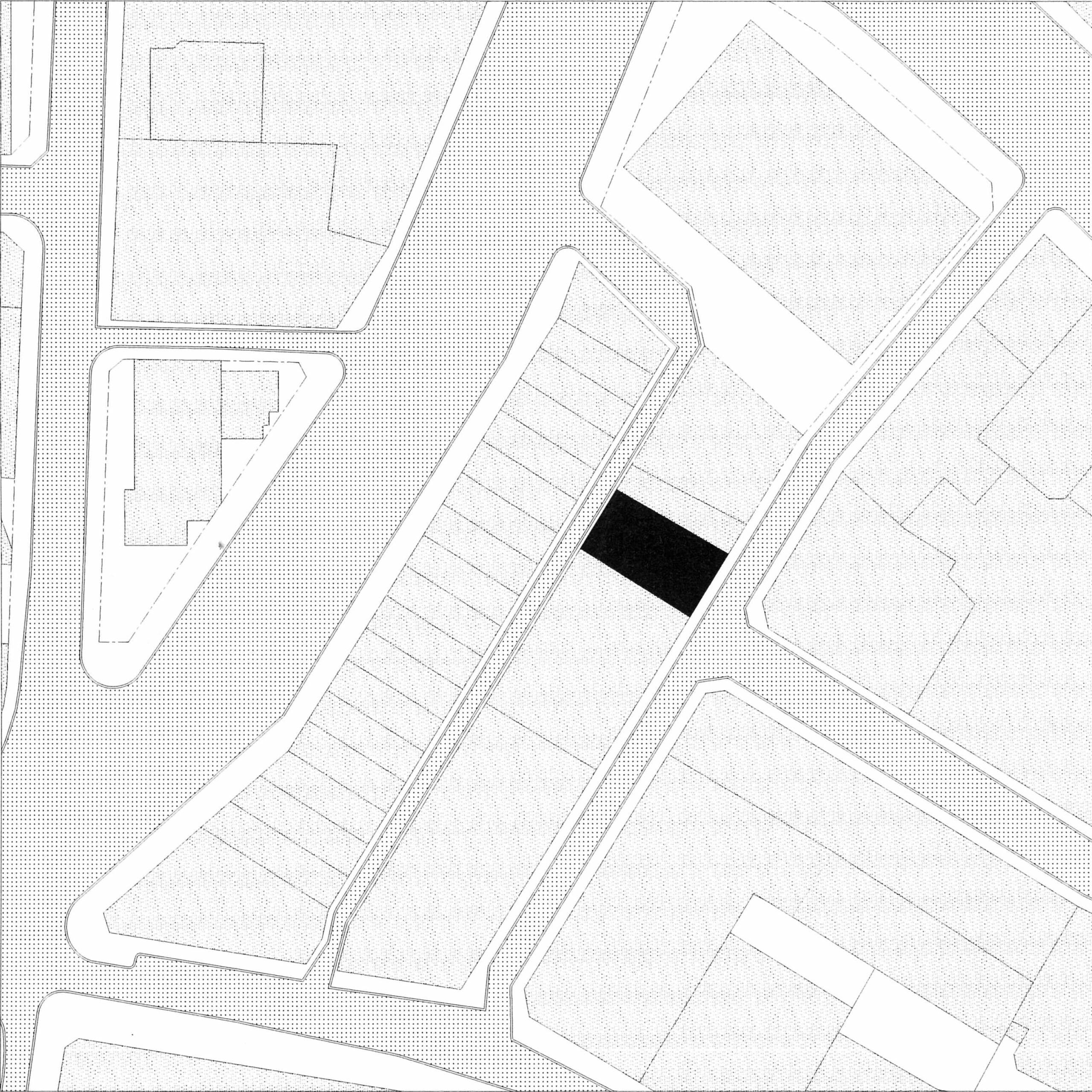

Case study 1: 9-25 Commonwealth Street

9-25 Commonwealth Street is a three-storey office building on a corner lot. Whilst lacking the height of typical office buildings in the CBD, this once city outskirt example still carries the characteristics of an infill building; a plan tracing lot boundary, repeated facade modules, sharing of party wall(s), and its small-scale fabric. Developed by James Hardie Trading Co., and designed by architects Hedley, Carr, Allen, and Watts, this building was completed in 1964. Today, 9-25 Commonwealth Street will too become tall, like many of its more recent neighbours, under DA/2014/1323 designed by FJC Architects. A 31-story mixed-use residential tower has been approved for the site—amongst the works will be the complete demolition of the building and its composite concrete, brick and steel structure, and three facades to Commonwealth, Clark, and Alberta Streets. These facades are comprised of shear exposed brick walls, or brick infill walls covered in textured cement render—above which sit bays of 3 windows. The glazing modules are divided by vertically running aluminium extrusions and are partly covered by framed suspended aluminium louvres. There is not much else to this facade, besides its black granite-clad basement that exposes itself as the street-level slope falls, creating the familiar and local Sydney rustication.

Case study 2: 17-19 Brisbane Street

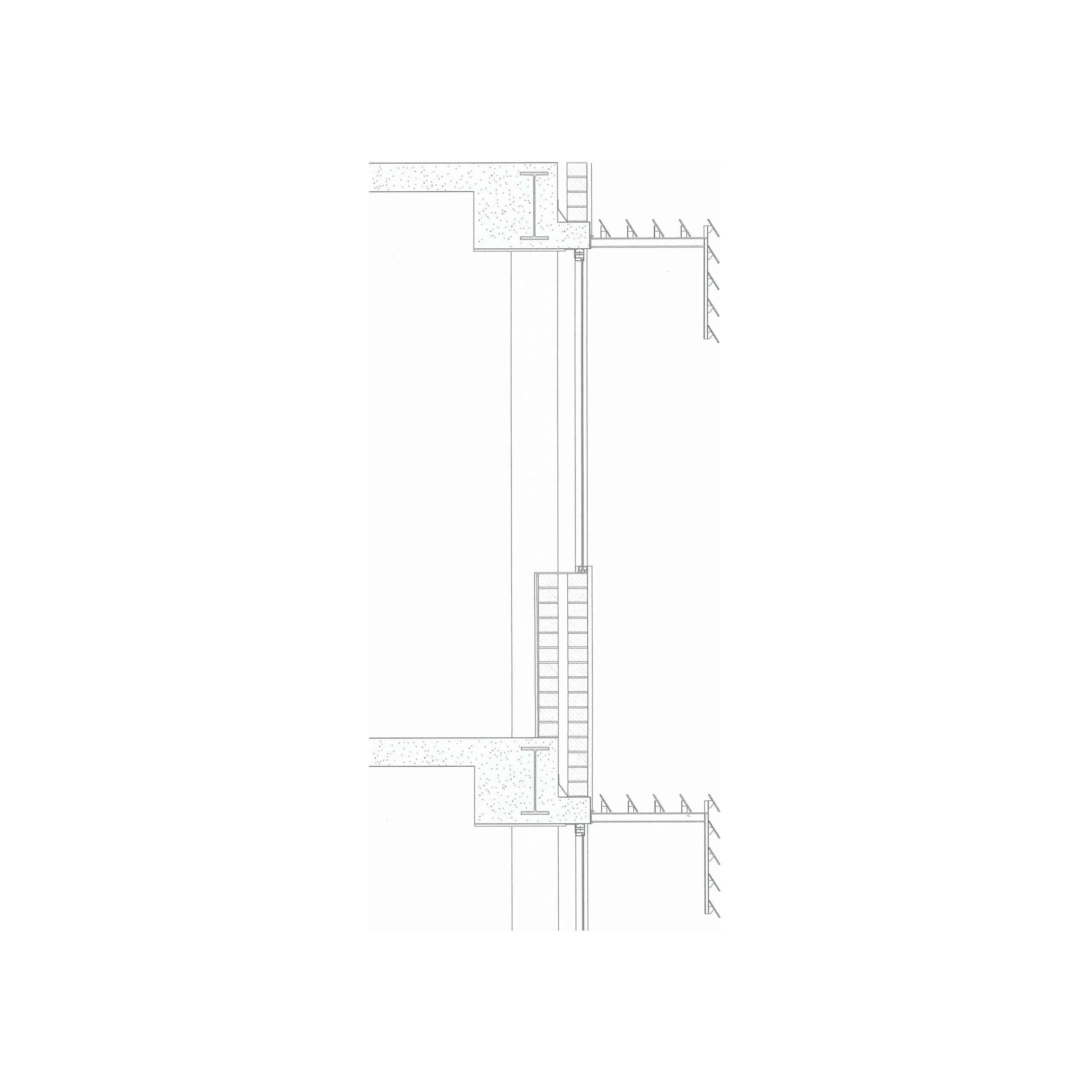

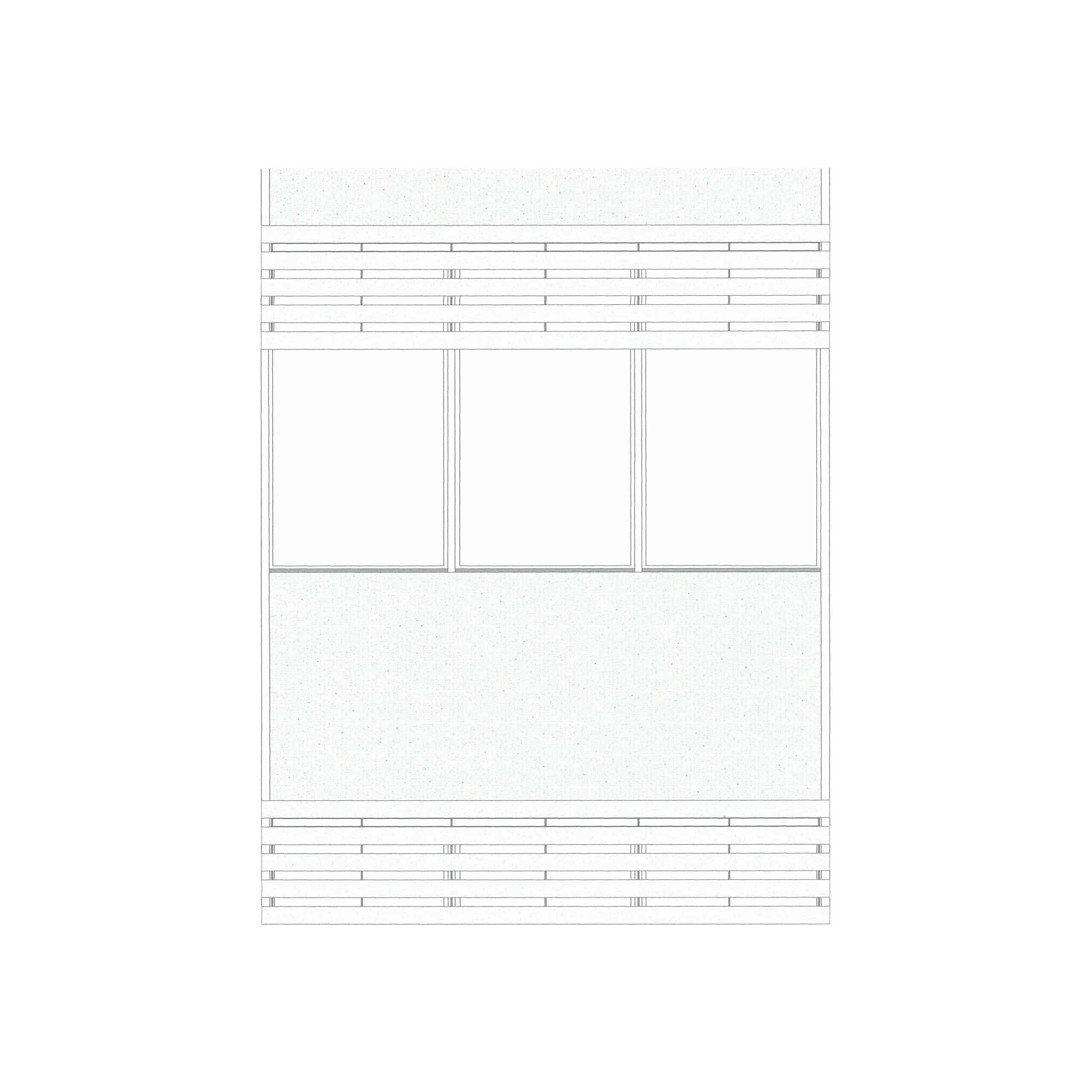

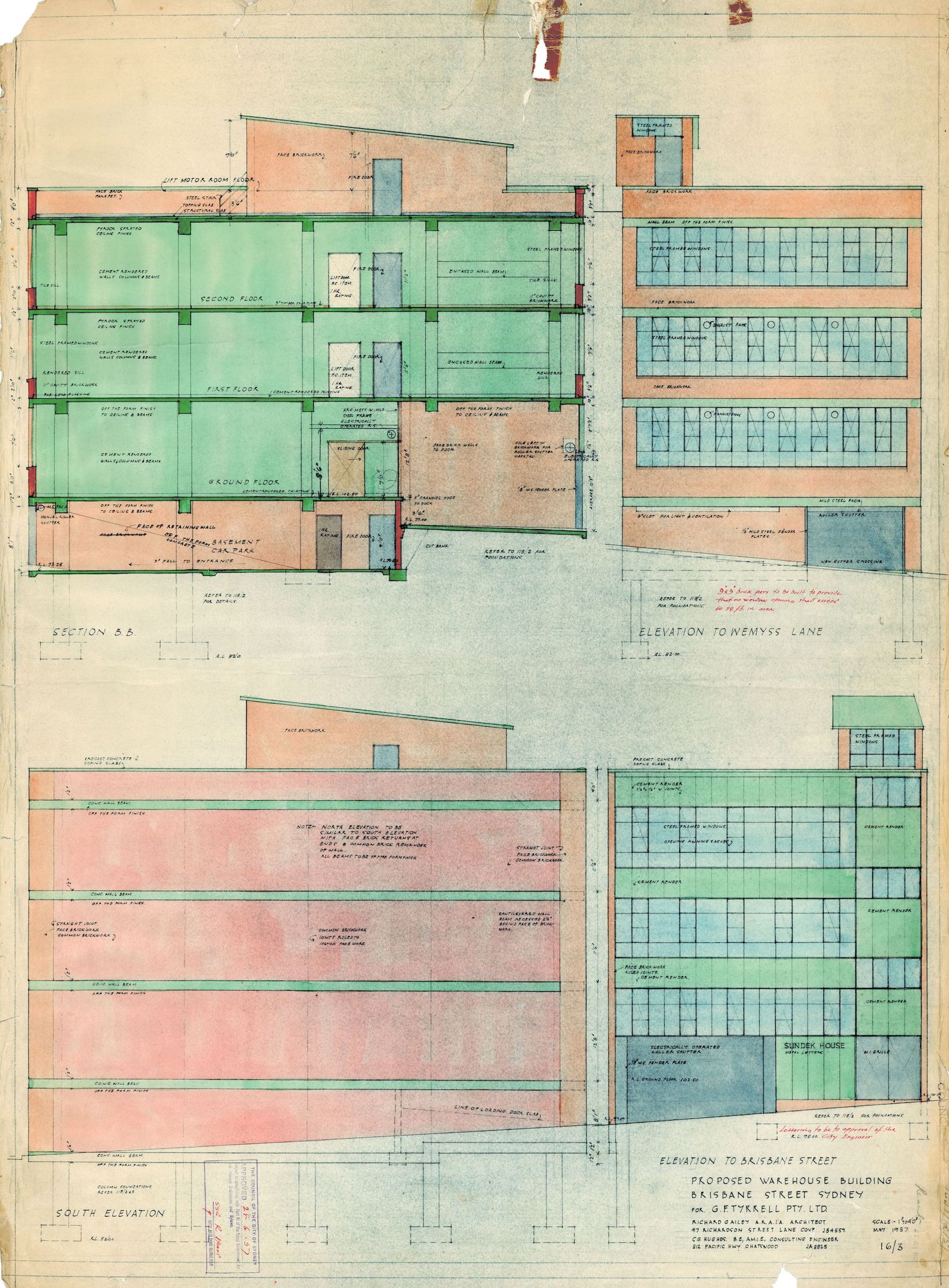

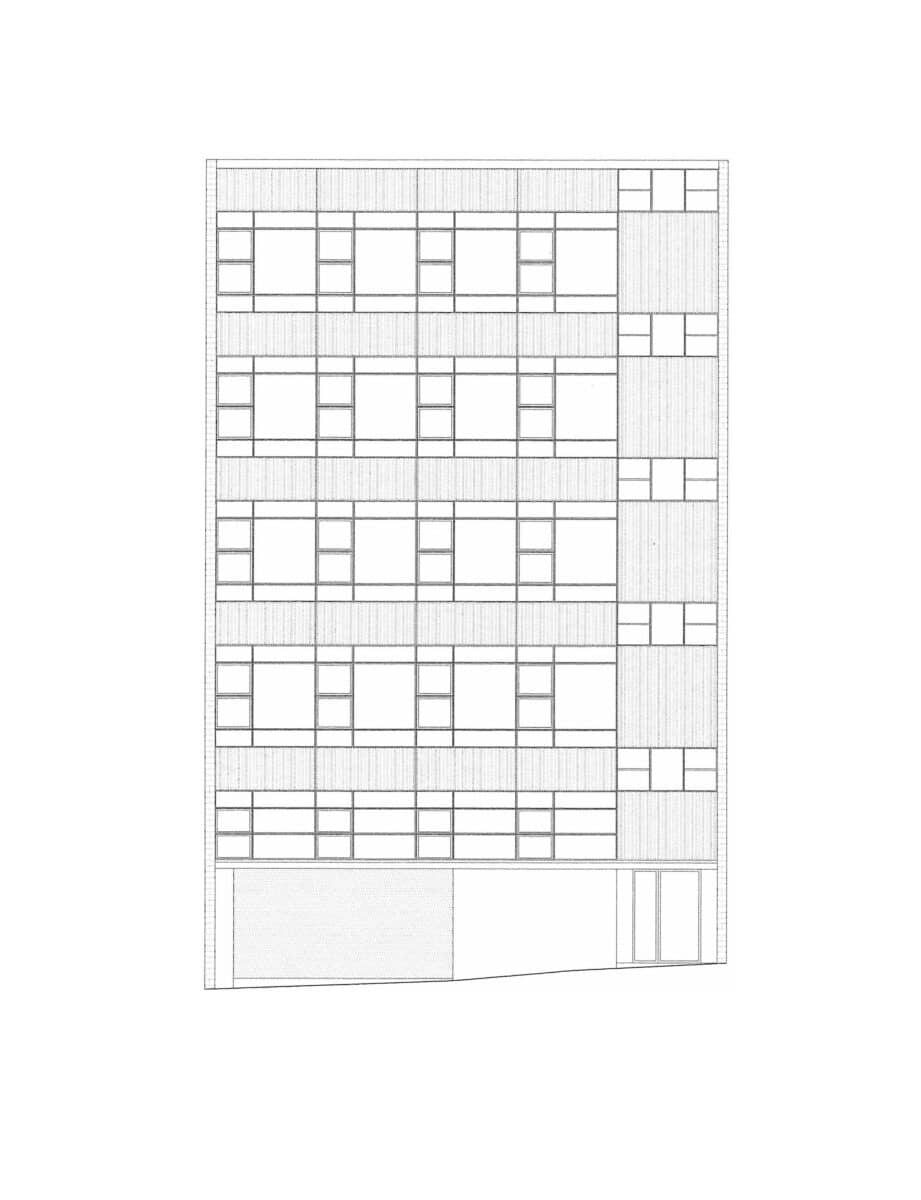

17-19 Brisbane Street is a six-storey office building, originally designed by A.R.A.I.A Architect Richard Galley and completed in 1957. The building, also known as Sundek House, later underwent alterations in 1968, seeing the addition of 2 new storeys. The original building was constructed with cavity brick party walls and columns that supported concrete floor slabs. This structure was later strengthened with steel and extended with a concrete-encased steel structure for the added two storeys. The facade was carefully followed in the alterations and additions process, with the glazing modules and infill walls copied to match directly above. The original brick infill walls that were once covered in cement render, were replaced with a profiled aluminium spandrel that presented a renewed facade but one consistent with its 1968 alterations. The elevation reads as 5 bands of 5 modules; 4 matching and 1 odd. The matching module consists of a profiled aluminium spandrel to hide a slab edge and provide ample sill height, as well as a grid of 7 glazing panels configured so that 2 are operable and the rest are fixed. The odd module, in the same materials, provides a taller spandrel—to match the window height of the matching module, hiding the stair that sits behind. The window height corresponds with the adjacent spandrel allowing light into the core. The brick edge of the party walls remain exposed and frames the facade. After the building’s recent anonymous sale in 2022 from former owners The Philatelic Society of NSW, any future development is uncertain.

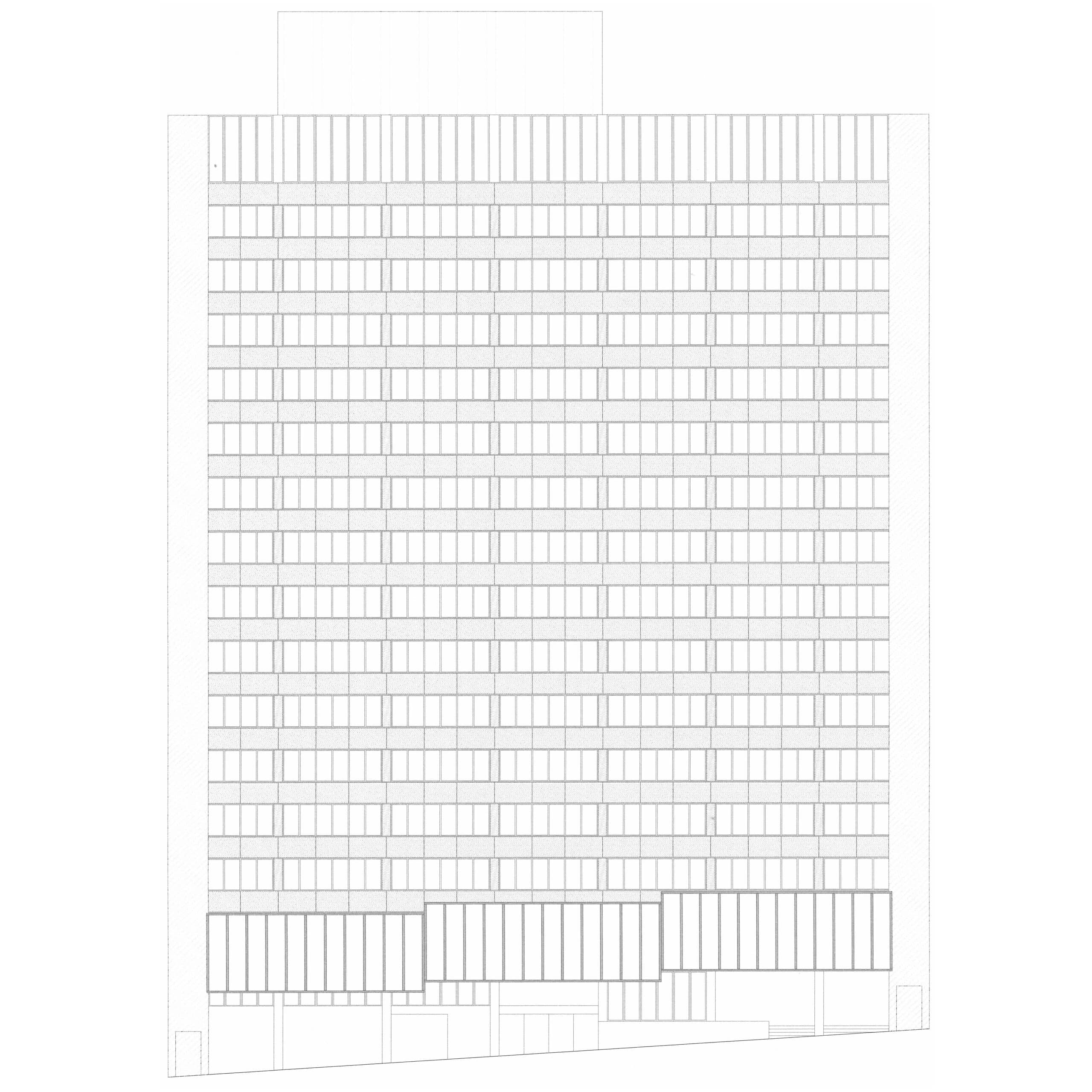

Case study 3: 189-197 Kent Street

189-197 Kent Street commonly known as ADC House (Australian Development Corporation), is an eighteen-storey office building with street level retail. Originally designed in 1963 but later opened in 1967, ADC House was in good company with direct neighbours Caltex House and the IBM building across the street. The building itself housed the Ethnic Affairs Commision of NSW, the NSW Government Printing Office, and later Grazcos Computer Services as the building gradually privatised.

The original and still-existing concrete structure, allowed for a free-form plan and non-load bearing facade. The 1963 facade consisted of precast concrete block work infill walls, clad in precast concrete panels. It was later upgraded in 1987 by Group Architects, who introduced its now signature blue aluminium spandrels and glazing tint. The elevation today reads as clear 36-metre horizontal bands of blue spandrel below seven bays of four to six aluminium framed windows; allowing for a reading of the building’s structural rhythm, these bays are further divided by dark blue spandrel panels that face the concrete columns. The facade itself is framed between two risers clad in silver aluminium and sits atop navy blue granite tiles on the ground floor. This very blue facade seems to belong, didactically, in its harbour-side corner of the Central Building District—especially amongst its many blue-tinted neighbours.

An approved development application (D/2021/690) designed by FJC Architects will see the complete demolition of this building and the erection of two towers (one of 25 storeys and one of 33 storeys) as part of a new build-to-rent and mixed-use development scheme. An excerpt from the Stage 2 Heritage Architect’s, Design 5, report states the following: ‘The existing building at the subject site has been substantially altered internally and presents as a representative example of its type with little intrinsic significance. As it stands today, it does not offer an important contribution to the urban fabric or streetscape and the former surrounding context and development from the time it was constructed is lost’. [1]

This research was generously supervised by Guillermo Fernández-Abascal, founding partner of GFA2 architects and Practice Fellow at the University of Sydney.

Notes

- Design 5 Architects (April, 2020). 189-197 Kent Street, Sydney, Stage 2 – Development Application Heritage Impact Statement (D/2020/399) Page 18. Retrieved from City of Sydney ePlanning services: <https://eplanning.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/Pages/XC.Track/SearchApplication.aspx?id=1475625.> Accessed November 2023.

Ellie Skinner is a sessional academic and editor of Paradise Journal.

Currently based in Sydney, she is looking at the construction of buildings and their local material figurations.