The Conservative (1941)

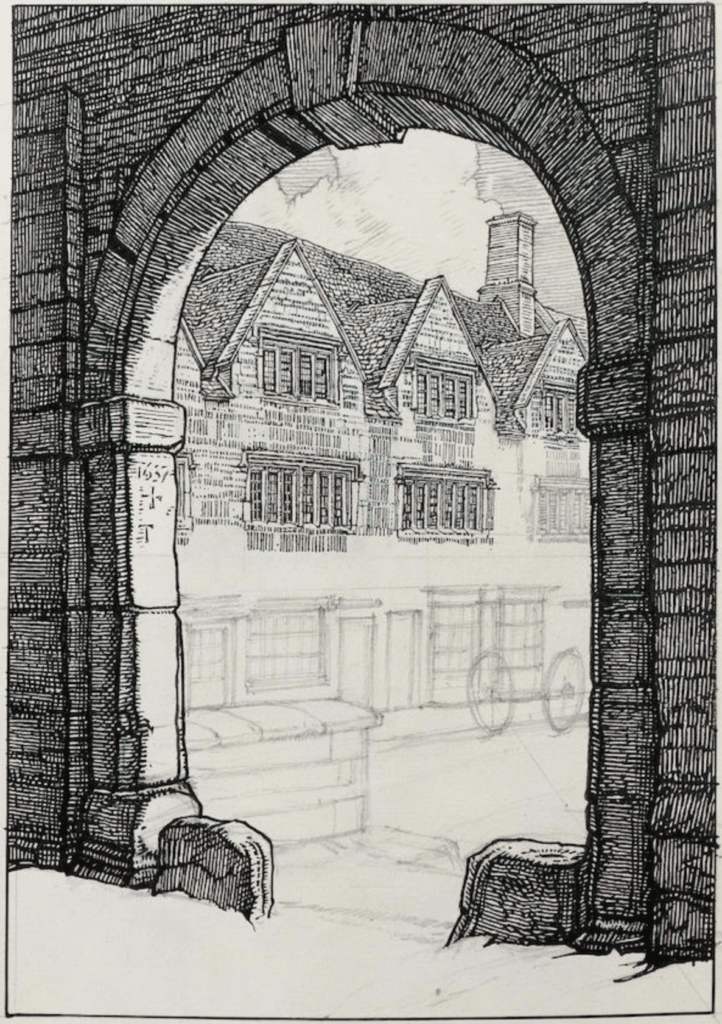

All along the wide stony high street of Chipping Campden one is aware of stopped clocks. Time has been strenuously and persistently defied – almost successfully. Even the public telephone box – after a short struggle with the Post Office – has been allowed to wear the protective colouring of Cotswold stone. At one time a lady did rebel, painting her seventeenth-century door scarlet, but the slow pressure of well-directed public opinion won in the end. Everything here is preserved – even the smells. So remarkable an attempt to halt the passage of time is of more than local interest: its success can be judged in the late F. L. Griggs’s drawings now published, together with an introduction by Mr Russell Alexander. [1] As drawings they are not of wide interest, but to anyone who knows Campden they will recall very vividly the geography of this strange experiment in escape – with its stone continuity of building from the fourteenth to the eighteenth century, as if the mind of man here had always taken as his main motto: ‘Conserve’.

No one conserved more passionately than the late F. L. Griggs: he built his own house of solid stone with little mediaeval rooms, no telephone and no electric light. New bungalows and workmen’s cottages were pushed under his leadership beyond the imaginary walls of what was in effect a dream town – they littered the road to the station and the road to Broadway, which was always to Campden an example of a town that had not sufficiently conserved. Griggs was a Roman Catholic, and so were most of the inhabitants of Campden. He believed in guilds and the love of craftsmanship: he had a mind’s eye picture – which he sometimes engraved – of what an English town had been like before the reformation, and to this he wanted Campden to conform.

But when you begin to conserve, you conserve more than you ever intend. Griggs had not meant to conserve the puritan spirit, and he certainly had no intention of conserving the slum cottages where women had to sleep in wet weather with a basin on the bed to catch the rain, or the one pump which served a whole hamlet. Some of Griggs’s impressions are given in his friend’s introduction – the qualities of the stillness and the light, the sound of bells and the smoke of jam-making; he tells us of the old names still left: Poppetts Alley and Calf Lane and the Live and Let Live Inn. There are anecdotes of old atmosphere – Mrs Beales saying of her husband, Noah, ‘Twere a bit thoughtless of him to die just as the currants wanted picking’, and Mrs Nobbs avoiding an aristocratic festivity in a local park, ‘I didn’t go, for I shouldn’t a knowed nobody, and what with the junketing and the music I should ha’bin fair moictered. So I spended the day in the Churchyard amongst the folks as I knowed, areading of their stwuns’. It is tempting to believe that by conserving the architecture you conserve such simple, wise, patient people as this – but is it true? In any case you conserve, too, the imprisoning conditions which led, as I can remember, one young married woman to leave home early of a winter morning, walk the three miles to Batsford Park, and break her way through the ice of an artificial lake until she reached a depth where she could drown.

The ghost of the dancing bear that haunts the pump at the bottom of Mud Lane, the ghost of the great hound on Aston Hill, out of superstitions like these it is easy to construct a dream town where unhappiness has the faded air of history. But to live there you must build the walls, not round the town, but round yourself, excluding any knowledge that the ye doesn’t take in – the strange incestuous relationships of the very poor, the wife starved to death according to country gossip, the agricultural labourers who lived on credit all the winter through.

‘The Conservative’ (1941), excerpted from Graham Greene: Collected Essays (London: The Bodley Head, 1969), 359–361.

Notes

- Campden: xxxiv Engravings after Pen Drawings, by F. L. Griggs. R.A.

– A. Trystan Edwards