The (Im)possible Palimpsest

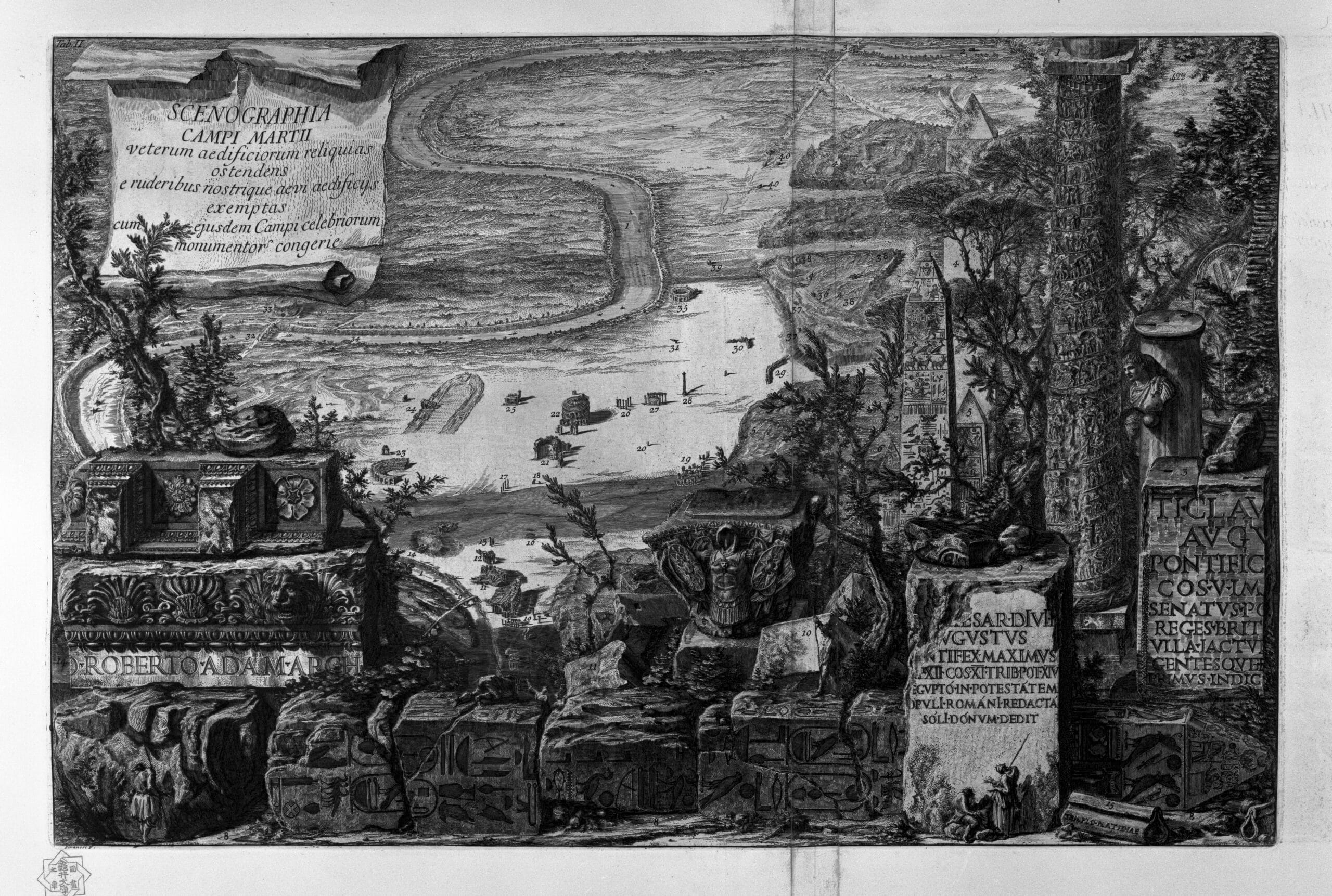

Preceding the Campo Marzio plan, a plate named Scenographia Campi Martii offers a clue towards an understanding of Piranesi’s work—the terminology is fundamental, the word Scenographia is purposely chosen to make a direct link to the theatrical representation and scenic design, often investigated by Piranesi. The image presented in this plate is constructed using the technique of the veduta per angolo: it shows monuments that have become ruins, precisely located within the broader, precise topography; the passing of time is acknowledged, but the whole composition is generated by the erasure of history and the layer added on top of the depicted area. A clear contrast is made, negation and affirmation of historical values.[1] Imagination enters the play, shaping the space in which Piranesi’s work lies, together with representation and classification.[2]

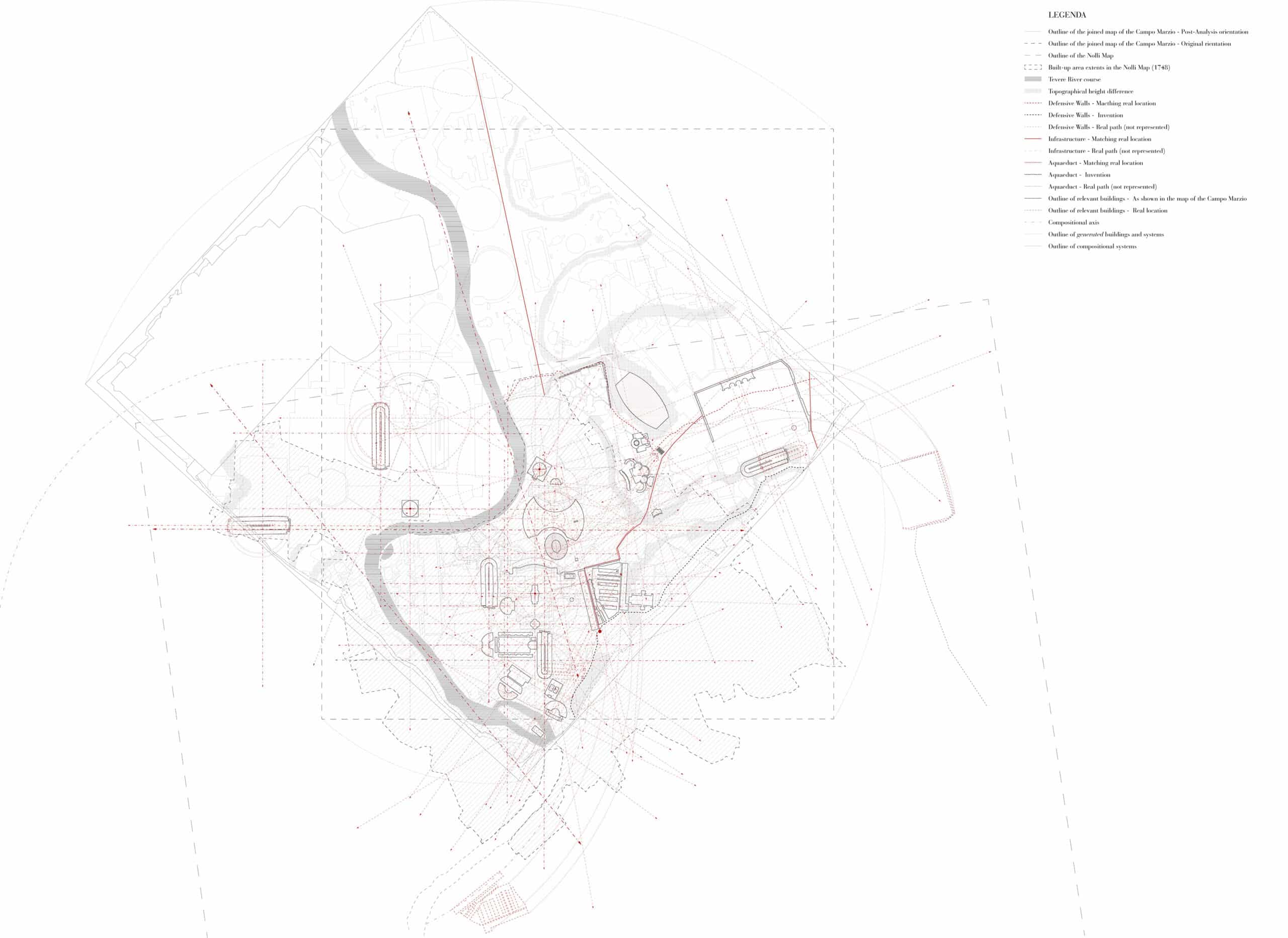

All of this is translated into the plan of the Campo Marzio, the medium through which it is presented, a representation of a representation—a rotated map of Rome, oriented the same way as the Scenographia Campi Martii, following the canon of the veduta per angolo, a process of de-familiarization from the context. Reality undergoes a double process of aberration, allowing Piranesi to break free of any possible limitation given by the time, the space, or the act of cartographic representation and production.[3] What is presented is an image of a Rome ‘that could have been’, where multiple timelines and multiple spaces come together into one composition—an impossible palimpsest is created.

The Campo Marzio needs to be disassembled and re-conducted to its genesis: real and imaginary must be contrasted and compared, the systematic approach of removal and relocation of elements must be reversed, the composition must be synthesised to a series of axes that follow a hierarchy, linking different compositional systems, holding together elements, generating new systems. Only through the explosion of the whole into pieces, in a sort of de-layeringprocess, the full composition can be comprehended.

The isolated layers can be grouped by three fundamental concepts: elements of the landscape, natural and infrastructural; urban elements; and intangible elements. An order is found in the seemingly chaotic and arbitrary composition, this newly found order allows us to understand how the whole design is a juxtaposition of fact and fantasy that come together in the form of a bent reality.

This analysis of Piranesi’s work is conducted with digital tools, ideologically opposite from the original technique of etching, and thus posits questions on how the digital medium can challenge the very notion of scale, a foundational principle in the act of drawing with analogue tools. Unlike the act of physical drafting, where scale governs both the process and the outcome, digital drawing operates within a space of potentially unlimited dimensions. In the almost surgical operation of disassembling Piranesi’s Campo Marzio, it became necessary at times to go beyond the 1:1 scale of the original printed version, and create adaptations that matched the dimensions of Rodolfo Lanciani’s Forma Urbis Romae, originally measuring 5180 × 7130 mm. To facilitate this comparison, Piranesi’s plan was digitally scaled to approximately 2:1 and placed within a canvas measuring 7130 × 7130 mm, allowing for expanded possibilities of interpretation within the digital framework.

Notes

- Stanley Allen and G. B. Piranesi, ‘Piranesi’s “Campo Marzio”: An Experimental Design, in Assemblage, no. 10 (1989), 70-109 (70), https://doi.org/10.2307/3171144.

- Vincenzo Fasolo, ‘Il Campomarzio of G. B. Piranesi’, in Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura, no. 15 (Rome: 1956).

- Manfredo Tafuri, Sphere and the Labyrinth: Avant-Gardes and Architecture from Piranesi to the 1970’s, trans. by Pellegrino d’Acierno and Robert Connolly (London, England: MIT Press, 1987)p.25-55.

Mattia De Lotto is an Italian designer currently based in the Netherlands. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Iuav University of Venice and is currently pursuing his Master degree at the Faculty of Architecture at TU Delft.