The Order of Terror

This text is the fourth in a series by artist Deanna Petherbridge in which she comments on a number of her recent pen and ink drawings. The drawings use imagined architectural imagery as a metaphorical means to deal with complex subject matter about social and political issues. Read the introduction to the series, here.

When I started to draw Camp Covid in late March 2020, it was a response to lockdown and the ‘cessation of social contact with others’ … a moment not so very terrifying or alien to an artist who works daily in solitude.

I had been contemplating the aerial images and media reports of Uyghur internment camps being constructed in Xinjiang province in China, reflecting not only on the ugliness and banality of these structures but also the terrible speed with which they were multiplying. Their rigid geometries and repetitive grids devoured landscapes as rapidly as an unwilling population were marched into ‘retraining camps’ with propaganda photographs of people sitting at desks in long receding rows of enforced anonymity. Like the automaton movements of Chinese military marches, or those terrifying performances of robotised humanoids forced into total synchronicity in acrobatic dance displays, or attendance at politburo meetings, the power exercised over unruly bodies is an essential performative plank of totalitarian control.

Moreover, history teaches us that state-exercised genocide requires efficient means for the killing and disposal of unruly bodies … when ‘retraining’ and forced labour have run their course.

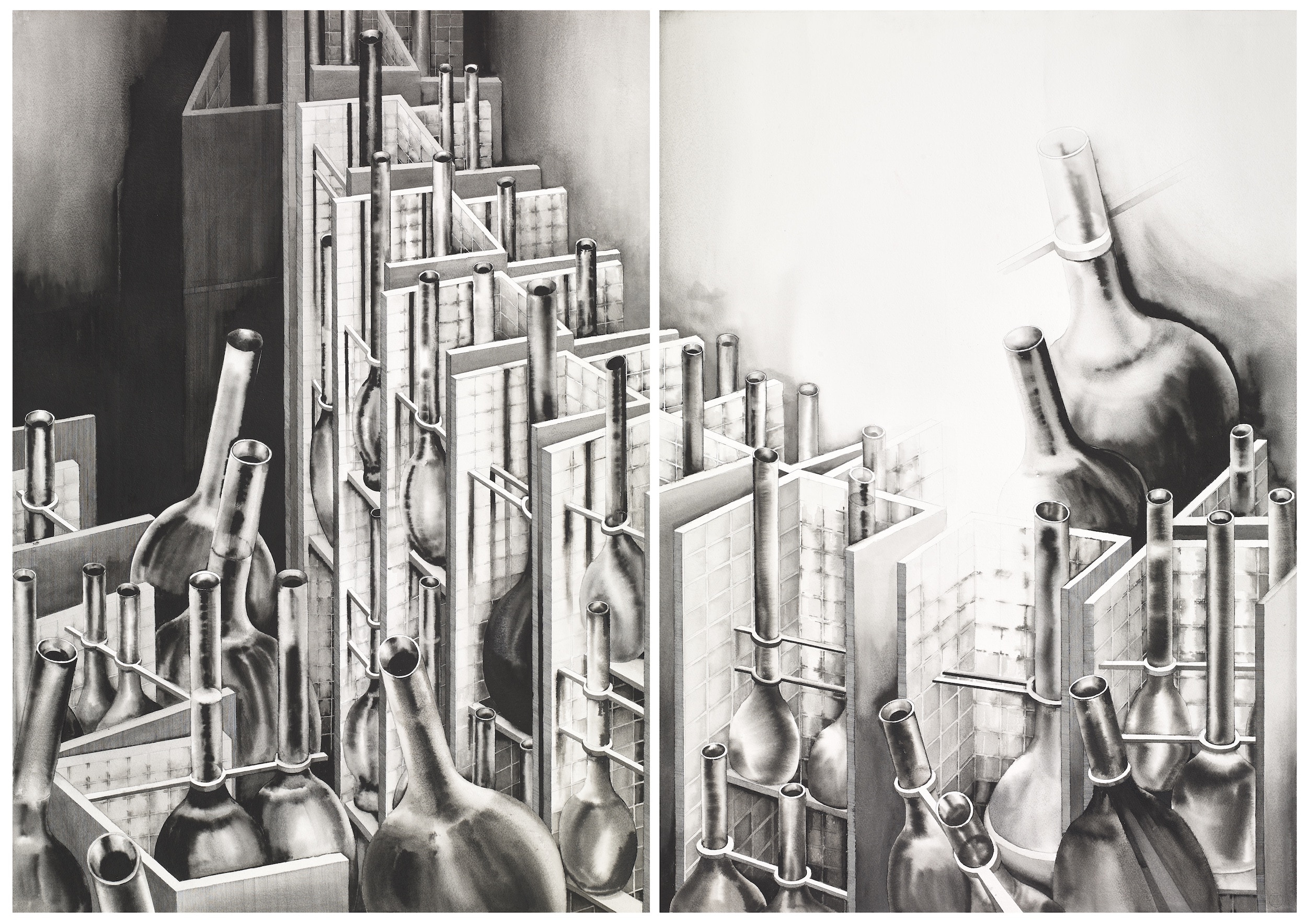

This was the thinking behind the extended gridded and monotonous landscape of Camp Covid, stretching beyond the frames and edges of the two panels in all directions into what art historians refer to as a ‘field’ view. Like all the inchoate thoughts that I have been unravelling in this series of articles, these concepts and their formal translations only became explicit to me as the drawing developed. Whether these gridded blocks are tomb structures built over graves or the tortured symmetries of concentration camps is open to the viewer’s interpretation. I cannot supply any visual analogies for the simple vertical crutch elements that emerge from the open blocks, although an ex-student of mine who attended a Zoom presentation of this work commented that they reminded her of the metal stands for drips attached to patients in the cubicles of the huge temporary Nightingale critical care Covid hospitals of the early UK pandemic.

There are no dramatic contrasts of tonality. I kept the double image to shades of grey ink in order to enforce the dreary monotony of the contoured grid. The bright white of the paper support is maintained only in the top planes of the sprouting crutch elements and the raised elements over two of the hollow structures that could be transparent glass planes. The literal references of the stacked planks have been questioned by an observer who knows my work well, but the work is finished and has to remain as it is. Once I have signed my circular monograph of Pi/Delta to a work I have to move on. This is one of my bizarre rules of engagement, and to quote Hélène Cixous in an essay about drawing/writing that I often return to (sometimes in refutation): ‘Our mistakes are our leaps in the night. Error is not lie: it is approximation’. [1]

Elsewhere, in the same essay, she declares:

I’m saying writing-or-drawing, because these are often adventures, which depart to seek in the dark, which do not do not find, and as a result of not finding and not understanding (draw) help the secret beneath their steps to shoot forth.

The cubicles of covid wards reappeared in a recent drawing High Covid: Constraint, contagion and pollution amongst tiled walls, medical flasks and mechanical restraints. I had been thinking – like all of us – about the effects of home confinement and necessary governmental restrictions. The elongated necks of my glass-fragile vessels poking out of domestic confinement were conceived as polluted and polluting phallic chimneys: simultaneously taking in and breathing out contagion. Some roaming blown-up flasks between the curved conurbations seemed to have escaped the restraints of medico/civil order in the manner of ‘fat-cat’ UK ministers and their advisors, so I’d hoped that the drawing would contain both menace and macabre humour.

Cixous interprets drawing/writing as the struggle of bringing something to fruition, as in a combat or battlefield. And I’ve belatedly been reading another Derrida-focused text of the same era, Catherine Ingraham’s Architecture and the Burdens of Linearity, which situates architectural drawing in relation to loss. She ends the book with a lament: ‘a reaction to an object that has in some way been lost’,

The building itself, as an object, first comes into our grasp … as a cultural, artistic, ideological artefact, by means of description. We have it completely or have it tentatively – have it as a design idea, an artefact, a fact – through the persuasive power of our descriptive narratives, geometries and visual models. [2]

This follows discussions about what is ‘proper’ to architecture, which she eventually defines as bodily habitation for the normative by architects rendered powerless by developers, planners and commissioning institutions and individuals.

Both these texts tempt me to a positive endorsement of drawing as a full-blooded activity humming with agency not just urgency. I want to shout from the roof-tops that my drawings and your drawings and all those linear artworks that are more than blueprints for construction, not models or diagrams of the would-be-real, not conceptual diagrams of the might-be-amusing or philosophical laments for the dispossession of symbolic power, are, instead potent spaces for the imaginative transformation of ideas into visual form in an ‘interregnum of criticality’. [3]

And amongst the operative principles of critical art-making that seem to have fallen off the teaching agenda must be the learned ability to make formal choices in the full knowledge of their implications, effects and affects: that is, discrimination in finding the most potent means of expression as the ‘proper’ tools of the visually adept. Not discrimination in its reduced single meaning of abuse against sex, race, religion or gender, but in its critical and democratic plenitude as an operative state of selection and discernment. Part of this tool kit of deliberative decision-making is an understanding of emptiness; of order, disorder and the informal states of the in-between; what kinds of line or tones or colour relationships to develop; what referential language and vocabulary to play with in the service of a work or series.

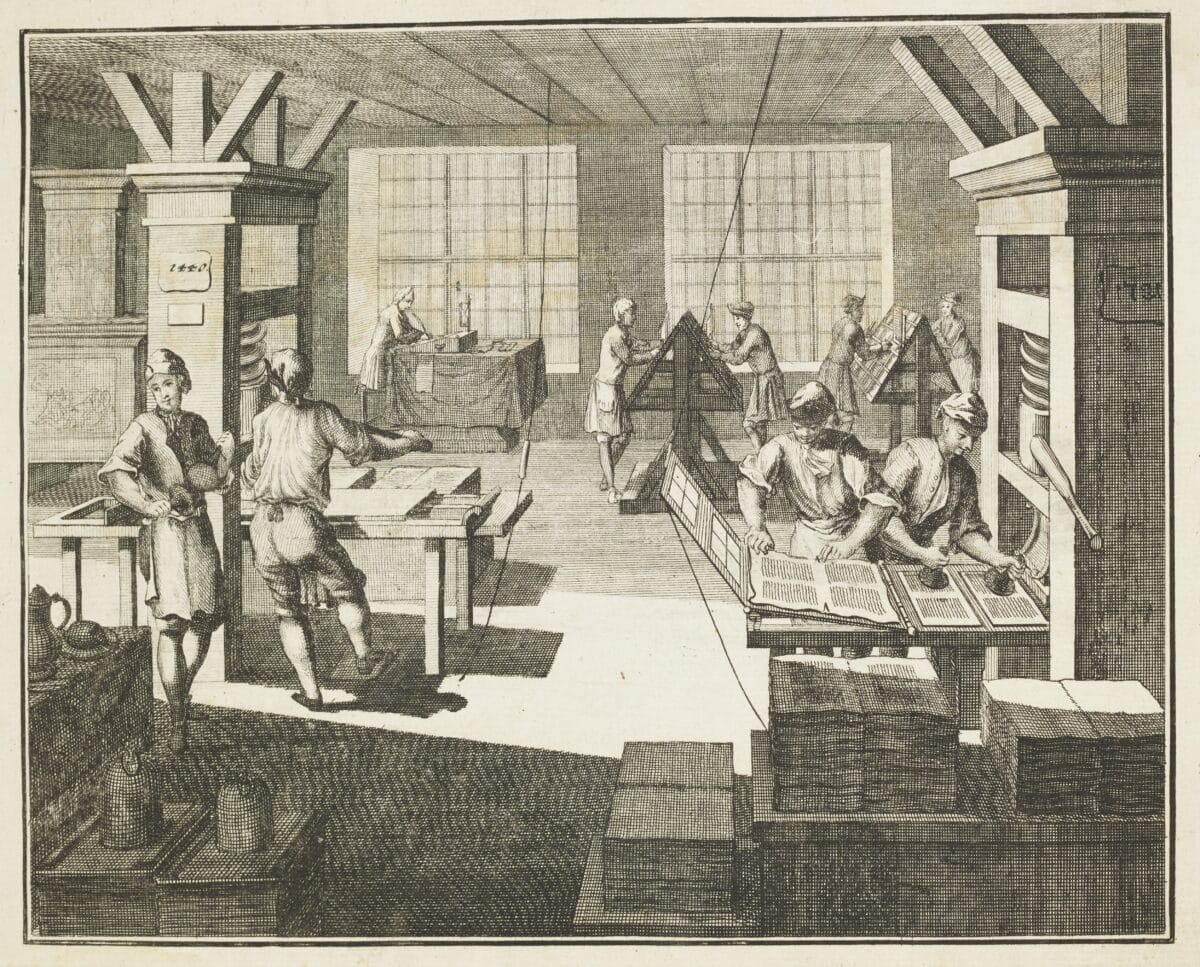

I thought much about this when reading Nicholas Savage’s recent review for Drawing Matter of Piranesi Unbound which was illustrated with a formal print of 1721. More unusual than the familiar engraved plates from the great Encylopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert (1751–1772), the ‘Interior of a Printing House’ similarly depicted an image based on a carefully constructed perspectival framework and a clarity of light and the falling of shadows worthy of a drawing manual [4]. And not a single piece of detritus in the workshop: everything immaculately clean, ordered, dust-free, empty, wholesome. Labour without pain, exploitation without need of historical revisionism, capitalism exalted in support of knowledge. The very cleaned up geometrically pure image of false ‘propriety’ that Ingraham had so engagingly deconstructed.

Long before I began to write theoretically about drawing, I turned to early black and white prints for visual inspiration in my own practice. I was as amused by their formal omissions as I was beguiled by the erosions of precision in their mechanical lines and cross-hatchings. What was edited out of these popular reproductive images was of immense importance because of the associated formal compensations of tone, line, composition, subject-matter, incorporated text etc., which made no pretence at reality or literalness. Our late nineteenth century, early twentieth century celebration of rhyparography (the painting of sordid or unpleasant subjects according to the definition of the Collins English Dictionary) seems to have come back in even greater force in the twenty-first century. We endlessly celebrate battle-free doodles and exuberant daubs and exalt drawing workshops for adults and children alike that ooze with the satisfaction of the un-edited and smudged laying on of hands without prior thought or plan. Artists regularly display such undisciplined and muddled scribbles as part of their own considered installations. As I’ve written before in this series, the performative act of drawing is nowadays considered more important than the product … in a world of over-production of electronic imagery and worship of self-display.

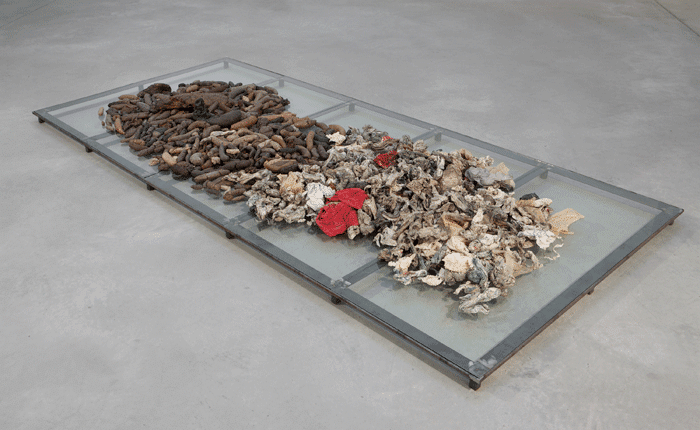

The Greek word ρυπαροζ means dirty, filthy, odious, vile. I believe that’s where a lot of politics are descending these days, but firstly I want to pay homage to an artist of my generation, Stuart Brisley. Probably the most influential performance artist in the UK, he has tested his own body and audience reception to extreme degrees. He published a book Beyond Reason: Ordure in 2003 [5] concerned with ‘shit, dirt, trash, waste, pus pollution and dogma’ and further explored the theme with his Museum of Ordure, which was included the exhibition ‘Museum Show, Part 1’ at the Arnolfini in 2011 [6]. Through processes of ordering, selecting and handling bodily waste he questioned: ‘Can the “body politic” ever be anything than a polluted body?’

Unwanted, discarded debris induces choking urbanisations, smearing land and urban-scapes alike. It thrives in the sway of the brutalising exploitation of natural materials and processes usually dealt with elsewhere … The interchange is filled with abrasions, natural disasters, and human sacrifices.

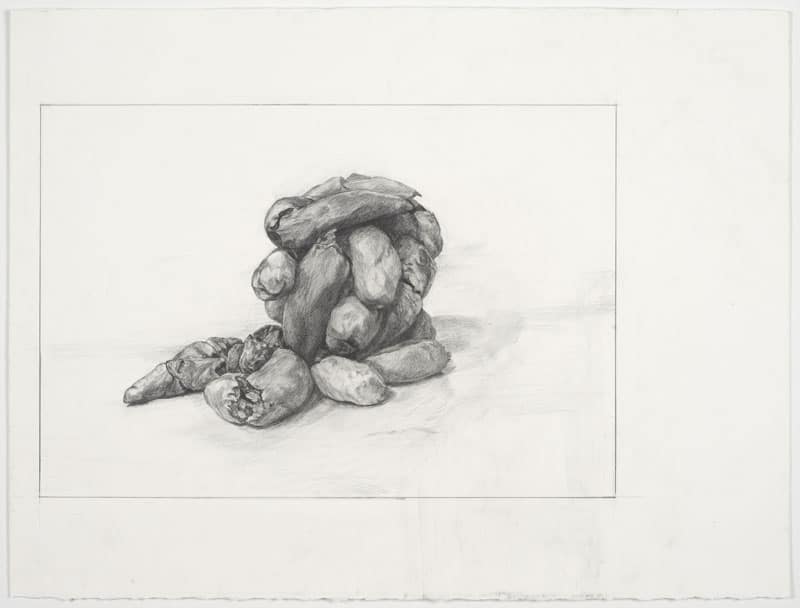

Even better than this elegantly labelled and displayed taxonomy of shit on a sparkling glass plinth, I’ll conclude with one of his immaculate ordure drawings. The work displays an economy of graphic means, careful placing on the page and a focus that depends on radical and informed selectivity.

The Order of Ordure? There is nothing more to be said.

Courtesy of the artist.

Notes

- Hélène Cixous, ‘Without End no State of Drawingness no, rather: The Executioner’s Taking off’, New Literary History 24 (1993), 87–103. Translated by Catherine A.F. MacGillivray.

- Catherine Ingraham, Architecture and the Burdens of Linearity (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1998), 115.

- I confess to borrowing this phrase from Ingraham, Architecture and the Burdens of Linearity, 46.

- Interior of a Printing House, in Johann Heinrich Gottfried Ernesti, Die Woleingerichtete Buchdruckereÿ (Nuremberg: Gedruckt und zu finden bey Johann Andreä Endters seel. Sohn und Erben, 1721). Princeton University Libraries, Rare Books and Special Collections.

- Stuart Brisley and Martin Craig (ed.) Beyond Reason: Ordure (London: Bookworks, 2003).

- Museum Show, Part 1, Arnolfini, 23 September 2011–18 November 2011.

– Nicholas Savage