The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect: Part III

This is the final of three extracts, each a series of vignette studies; they are all taken from Kester Rattenbury’s fascinating full-length study: The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect, which approaches the great author from the perspective of his first career as a young architect in London and Dorset.

As he established himself as a novelist and poet, Thomas Hardy gave up architecture as a profession, but that early experience both directly and indirectly remained an inescapable presence throughout his written work and in the development of his vision of Wessex – and also at Max Gate, the house that he later built for himself and his wife.

– Niall Hobhouse

Tess Maps

There are two key Tess maps remaining. One, ‘Tess’s Wanderings’ is Thomas Hardy’s own, marked-up copy of ‘Cruchley’s Railway and Telegraphic Map of Dorsetshire’, a highly detailed railway map, with Tess’s routes and destinations drawn on it by Hardy, in detail. It is a story largely contained in a single map sheet with Tess’s walks drawn in red and with crosses also identifying key navigational points – often hilltops and viewpoints. For although Cruchley’s map is very detailed, the topography – the shapes of the hills – can be sketchy.

The other, ‘Tess’s Country’ (published in Harper’s magazine in 1925), is a smaller, retrospective map. It is of the familiar Wessex type: drawn freely and confidently, in proportion, with an assured sense of what matters – as architects do retrospectively ‘sketch’ their fully achieved projects. It is a return to The Bookman map – and specifically, to being a railway map. It even updates the network, adding the new South Western line through the vale of Blackmoor. Like the drawings in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, this is both a map of a place, and the structure of the story. Tess’s ‘wanderings’ – literally – describe Wessex.

Yet the book only touches those railways. The main parts of the story happen in the spaces between them: the unnamed range of hills and the broad, open valleys. But the map clearly shows a network of lines as the organising structure: the infrastructure which set out the conditions of the story. Hardy is showing the framework between which Tess’s life fell.

The Wessex Poems

The Wessex Poems, published in December 1898, was ‘unique in being extensively illustrated by its author’. [1] What is riveting, architecturally, is the way Hardy made the book, obsessively generating the pictures as a way of realising and assembling the poems – some of which he had written decades before.

He called it ‘A mysterious occupation.’ [2] ‘I told nobody I was doing the sketches as I was by no means sure that the attempt would come to anything’, he told his friend Florence Henniker. [3] There are 30 drawings in the book (or 31 if you include the ‘frontispiece’ in some imprints [4]) and he may have done others which did not make the cut. To another friend, Edward Clodd, he called them ‘a sort of illegitimate interest – that which arose from their being a novel amusement, & a wholly gratuitous performance which could not profit me & probably would do me harm’. It is notable that he was working in private. I have already suggested at least some of these might be the working up of pictures for which he already had, in some form (tracings, sketches, photos, Camera Lucida outlines or others) rough images from earlier in his life.

He apologises for the drawing quality, citing his ‘years of unpractice’: [5] presumably as an architectural draughtsman, possibly as a user of various drawing techniques too. He specifically says it was the drawings which drove him to revise the poems ‘so perfunctorily collected’. [6] This is an experiment both in drawing, and in publication, and in the greater ideas generated when you put pictures and texts together as architectural books always have.

Pamela Dalziel describes: ‘detectable tension between Hardy’s personal, creative commitment to the drawings’, and his ‘uncertainity as to their value either in themselves or as enhancements of the poems’. Hardy never seems to have resolved it, she adds; ‘and it was “responsible for several curious aspects of the work’s publication history”’. [7] That is another remarkably observant description of the working processes of design thinking. Hardy had by now delivered his working fictional-real Wessex, and was drawing out (in both senses) the various ways of imagination in which he could see Wessex – and try to project it to others too.

The pictures in themselves are startling. Many have the wide horizontal frame of vision which would only become normal with cinema and car travel (both the Smithsons and Venturis describe this mode of travel as re-framing experience). But they are also the wide horizons of Dorset itself: the sense of elevation and distance from its long, flat-topped ridges of hills, which Hardy could now see from Max Gate and explore by foot and bicycle (and later by car). The ‘new horizons’ of imaginary Wessex are precisely what he is imagining, drawing and constructing, in both content and form.

These drawings stretch the limits of vision. They show darkness, disappearance, the dazzle of low sunlight bleaching sight. They are also constructed inventively, as drawings. The vault drawing is set up as a conventional section, but humans, alive and loving, dead and decaying are drawn too. The coffin drawing is even more peculiar, with the stairs depicted in a flattened ‘planometric’, with shadowy outlines through the ephemeral coffin bearers: the coffin is solid. The ‘Tryphena’ drawing of the shrouded body is another surrealised ‘architectural’ drawing – the elevation of a sofa; the imagined corpse which suggests both monument, body and landscape.

Many of the drawings are composed and rendered exactly like photographs – with strong shadows, figures in silhouette and other photographic peculiarities: it seems unlikely that an architect would draw all of the accurate detail of Sherborne and not include the top of the arch. Many may have been set out by camera lucida: the landscapes in particular are peculiarly flattened. Others trap fragments of abstract thought in visible form: the image of Napoleon, hovering above a mass of bayonets as though in a song; or dance notation springing to life. As already mentioned, the vase of dead flowers takes its brief exactly from John Ruskin ‘It would be curious to see […] a painting of dead flowers.’ [8]

Others are more impressionistic, more like paintings: the view of San Sebastian at night (another unsettling body-landscape vision, discussed by Shires) or the shaded vision of the fiddle-player at the pub window (another picture of music). Many have a single, shadowy pre-Le Corbusier occupant, or the image used by Robin Evans of his own shadowy reflection in the Barcelona Pavilion: all itself suggesting an imaginative double-take: am I watching that figure, or am I that figure? Some are ravishingly successful; some look clumsy. But they could hardly be clearer evidence of someone thinking and working like a conceptual architect of the twentieth century.

They try to capture projected vision itself, to stretch and combine architectural drawing techniques to cover things they normally omit: time, death, darkness, shadow, music, ancient graffiti. One even shows a view through Hardy’s glasses in a type of picture of the act of imaginative vision itself which echoes through the architectural high ground – St Jerome in his study; Ledoux’s theatre reflected in the eye; Le Corbusier’s photographed glasses – which is deliberately ambiguous, as Keith Wilson says. [9] Either there was nothing wrong with Hardy’s eyesight or he was suggesting that Wessex exists both through his eyes and outside them. Bernard Tschumi says of his own similar drawings:

Developed in the late 70s, they proposed to describe an architectural interpretation of reality, to this aim they employed a particular structure involving photographs that either direct or ‘witness’ events […] At the same time, plans sections and diagrams outline spaces and indicate the movements of the protagonists, intruding into the architectural ‘stage set’. The […] explicit purpose was to transcribe things normally removed from conventional architectural representation, namely the complex relationship between spaces and their use, between the set and the script, between ‘type’ and ‘program’, between objects and events. [10]

Which could stand, word for word, against Hardy’s illustrations. The date alone is wrong.

All this is entirely on the home territory of experimental projects: the images which stick in the memory, the strange or inventive drawings, the testing and uncertainty. Pamela Dalziel turns drawings round to consider their different effects, which architects often do, [11] and describes how in different publications they were rotated or trimmed (I had been doing re-organisations myself to explore groupings or visual narrative). Even if such reconfiguration of pictures is rarely described (outside the specialisms of architectural research) this is native experimental architectural behaviour – and theory. Linda Shires, exploring speculative and ambiguous constructions made between picture and text, hits another architectural key idea in William Mitchell’s ‘Image X Text’. Pictures do not add to text, they multiply it, generating all kinds of possible readings. This is central to architectural theory and practice: how humans generally, and architects professionally, put pictures and words together to imagine working places, in their heads, all the time.

The Wessex Poems fall eerily into architectural prediction mode too. Shires is describing ‘Heiress and Architect’ with its coffin drawing:

The woman requests the architect build a palace for her with ‘high halls’ and ‘wide fronts of crystal glass’ […] As he refuses each request, she reduces them to ‘[a] little chamber’ or ‘[s]ome narrow winding turret […] Rejecting such notions entirely’, he states that he will build, instead, just space enough to ‘hale a coffined corpse adown the stairs’ […] The poem states but cancels her vision of the future and narrows space in the imagination. [12]

Emma Hardy had retreated to her attics around this time, when Jude was published; she would leave, by coffin, down that specially designed stair. As Shires, and many, many architectural writers quote from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, ‘texts hold virtual potentialities for their future reading’.

Hermann Lea

Hermann Lea was an enthusiastic local photographer who met Hardy while producing A Handbook to the Wessex Country of Thomas Hardy’s Novels and Poems. They kept working together, remaining friends for the rest of his life, forming ‘a real working bond’: ‘Lea was unlike most others who came at all close to Hardy: he was not gentry; he was not a woman; he was not literary, and he seems to have experienced a side of his friend that was less public and less reserved than most people were offered.’ [1]

In my terms, this is a key collaboration. [2] Lea was surely a better technical photographer than Hardy and he would do a mass of time-consuming work which Hardy would not have had time for. But the vision is clearly Hardy’s: it is what he has described in such detail, in writing, and in the Wessex Poems drawings: location, subject, focus, extremes of weather; framing, emptiness, the obsessive pursuit of the limits of vision, of vision itself – which he had already tried drawing through the Wessex Poems pictures. Hardy had effectively found a way of shaping the precise visual framing of Wessex.

Lea went on to produce the more obviously collaborative Thomas Hardy’s Wessex for Macmillan in 1913. It was published in the same format as the Wessex novels – Hardy was firmly authenticating, even perhaps claiming it, and Lea’s photographs were also used as frontispieces for the novels’ Macmillan Wessex Edition. [3] I would suggest that this collaboration was, like much of Hardy’s later and more inventive work, a rich, productive way of working; in which architects naturally cooperate and collaborate to get their visions realised, just as Hardy did on the maps and guidebooks.

This is not to deny Lea’s remarkable achievements and his really wonderful pictures: rather the reverse. Collaborations are a key form of creative practice: individual authorship remains an open question, and classically, in the successful ones, each person extends the other further than either would have gone by themselves. This is the multiplication, rather than addition, of creative work.

Lea went on to take many other wonderful photos – including the staged portraits of rural people, and some trick photography shown in Jo Draper and John Fowles’s wonderful book. But I had puzzled over the repeated use of the classic Wessex photographs (there were many published variants, including a popular motor-touring guide) since they often looked so dull and dumb. That was before I saw the collection of the photographs held by the Dorset County Museum, the ones sent off to the printers for Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, with Hardy’s own captions written on the backs – and returned to him with the printer’s mark-ups (drawn in the china-clay pencil used for layouts in the days before computers). These are the physical photographs, which Hardy saw (and Lea gave back to him) – and they are profoundly beautiful photographs, with astonishing levels of detail.

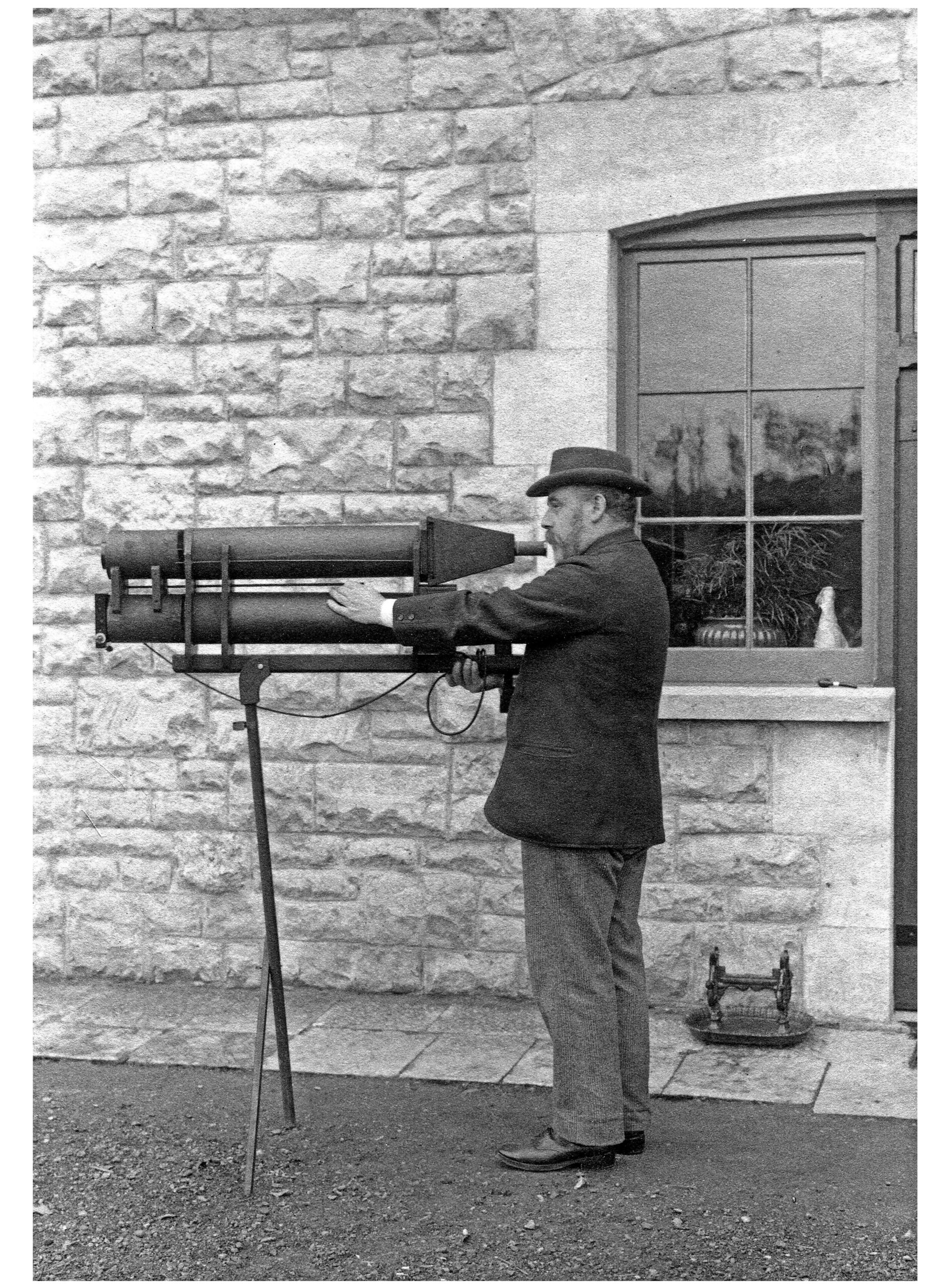

This was because of Lea’s remarkable camera – the home-made super-zoom which finally could capture Hardy’s long-lens vision of his emptied landscapes. Lea’s book does not describe the development of this extraordinary device, but Hardy had inherited a telescope from a ‘collateral ancestor’, and he had certainly researched telescopes for Two on a Tower, as well as possibly using a ‘graphic telescope’ and other lens devices himself. His telescopic vision, most notably in The Woodlanders and the Wimborne drawings, and his lifelong obsession with lenses certainly pre-dates Lea’s involvement – although it was only now fully realised.

This collaboration, and these photographs have been vastly underrated. For generally, they have been reproduced incredibly badly – muddy, greyish, and terribly poorly cropped. You can see from the printers’ marks how and why this was done. The sub-editor tended to chop out sky, or unoccupied land, when sky and unoccupied land were precisely what Hardy was showing us. He tried to crop these down into normal pictures: as though the meticulous, peculiar framing and focus of Hardy’s vision were not exactly how Wessex was constructed. Again and again, the reproduced, banal photograph is a travesty of Lea and Hardy’s carefully framed, intensively zoomed view. Hardy had finally found someone who could capture the scale and detail of his view, the value of vast, empty places – and a pragmatic sub-editor who chopped them all out again.

These are telephoto pictures of often empty landscapes; in often bad weather, showing the limits of vision with incredible clarity. Some are taken in deliberately appalling weather, like the amazing one of Wareham Heath which became the frontispiece to The Return of the Native. It is a good, moody picture in its full-page reproduction, but the print shows it was taken in a torrential downpour, water pouring along the track. Hardy must have had Lea out photographing, miles from anywhere, in all weathers. They were both, clearly, and rightly proud of that photograph – and I bet the sub-editors thought they were mad.

This was a preposterously ambitious endeavour. Lea had to cycle that massive lens around on a special trailer, behind his bicycle, to remote and distant places (until he got a car). It is no wonder Flintcomb-Ash, on the top of a hill, and way off the road in the 1880s – could not be found by Lea alone.

But there is no question we are seeing Hardy’s vision here. It is exactly the picture of the Wessex Poems, Tess and the Return: dazzle, distance, detail; absence, disappearance, a landscape emptied. He is taking us, always, to the very limits of visual perception. Lea called his own book Hardy Through the Camera’s Eye: that vast double-barrelled thing seems to be an SLR camera; they would both have been looking through the ‘Camera’s Eye’ – and they both enjoyed a pun. As in the Wessex Poems, Hardy is not just asking Lea to illustrate the stories or their settings: he is building up his assembled, diffuse, coherent view of Wessex as a whole.

The places photographed are personal as well (Fordington, Puddletown and Wimborne for instance) and he would continue to extend this photographic survey adding (and photographing) ‘local’ settings in his remarkable play, The Dynasts. The photographs – like the Wessex Poems – are a key part of the assembled construction of Wessex. They do not just show us pictures of the places. They show how to focus our own vision, to see Wessex the way that he did.

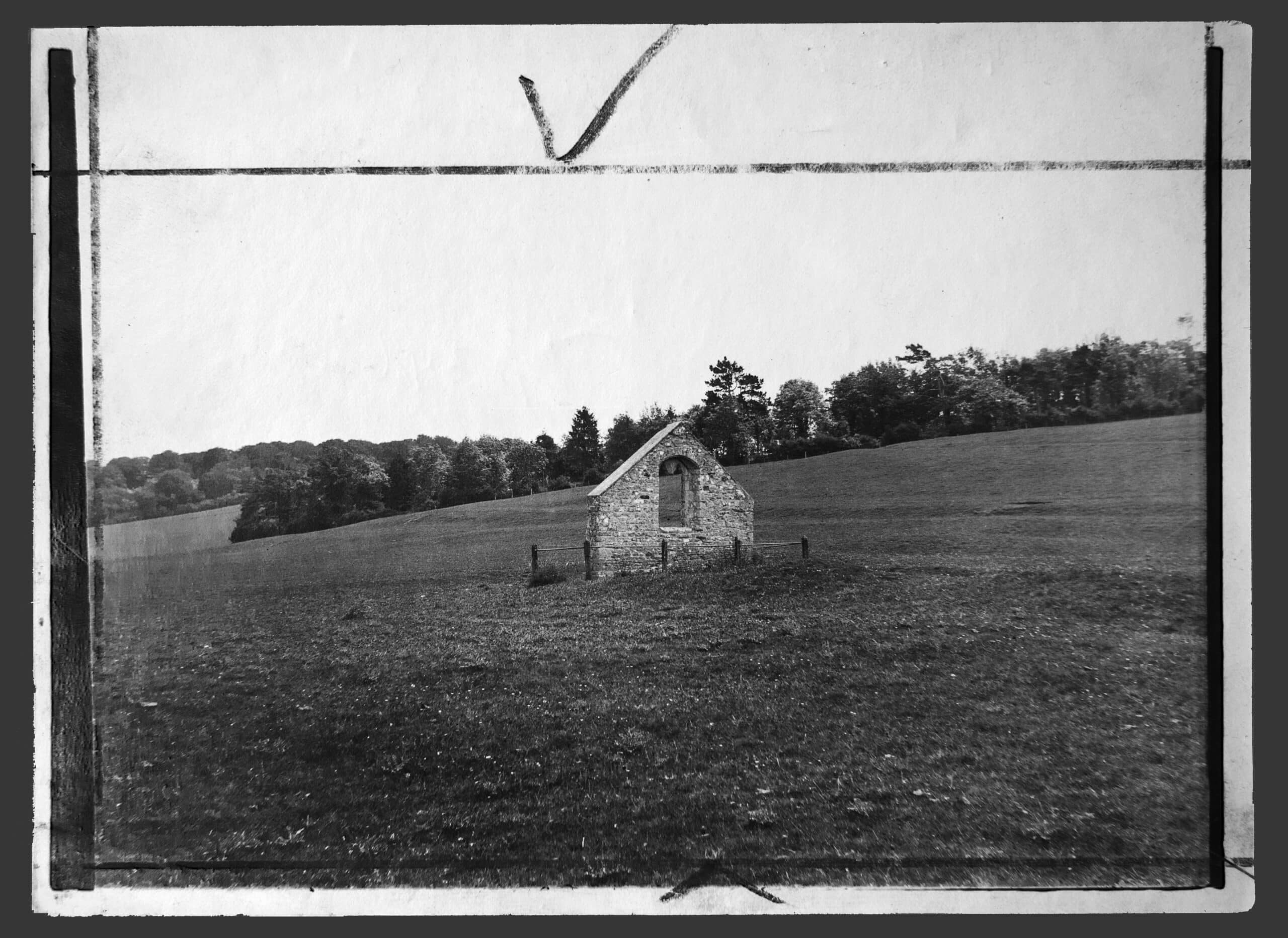

So the best ones are works in themselves. The exquisite photograph of Maiden Castle, taken in dazzling sunlight, looking as far as the eye can see, and further than history can remember. The strange image of Faringdon Ruin in its plain field: a key awkward remnant of such ‘vanished villages’. Or the view from the Wessex Ridgeway, looking towards Dorchester.

That photograph is a type of picture Hardy always returns to. It is a road, empty, running through an empty landscape, out of sight: the vision of Wessex. They are almost always old roads and they often open the books: Roman roads through Egdon Heath, Iron-Age ridgeways, sometimes mere tracks made by the passage of humans, or signified only by the fluttering of birds getting out of their way. It is the pedestrian’s view of an old human landscape, forensically recovered, through a modern frame.

You can see the human occupation of the landscape, used in a similar way, stretching perhaps twenty minutes ahead by foot, back beyond written history. Those drawings, photographs and descriptions are pictures of time and place itself, of the human in the world, seen through an inventive long-lens camera. Rather like Patrick Keillor’s film essays, [4] they show us how much we can read from an apparently empty view, if we really look at it, for long enough, as architects have to.

Lea’s work is central, architecturally, because it is a clear, constructed, highly experimental and clearly directed vision of how Hardy actually saw Wessex. It is another body of work in which Hardy, working closely and creatively with others, extends the substance of Wessex itself. These pictures evidence a very particular type of vision, from obsessively close detail, to vast visions stretched to infinity – empty roads; buildings lost in the mist, rain or sunlight – where we see the passage of humans across an empty land. This is what Wessex looks like.

Like the Wessex Poems, these photographs have not been seen in the way that a modern architect would see them. Mostly, they have not been seen at all, rarely reproduced well enough to show the remarkable way they were made, or how they stretch our vision to the edge of experience.

The Mayor of Casterbridge

In The Mayor of Casterbridge, Hardy reached a whole new level of evocative description, using new tactics as well as old, architectural as well as popular. That wonderful opening description of the town keeps changing, becoming more varied, more sensory and immersive. He tells us that the town ramparts were replanted as promenades, but he describes how the women move on through the dark tunnel of trees as ‘they passed down a midnight between two gloamings’. He moves us on, describing the town, snug and comfortable, its lamps starting to glimmer, a brass band heard in the distance; then he gives a quick, rich survey of the houses, architecture and furnishings alike:

…timber houses with overhanging storeys, whose small-paned lattices were screened by dimity curtains on a drawing-string, and under whose barge-boards cobwebs waved in the breeze. There were houses of brick-nogging, which derived their chief support from those adjoining, there were slate roofs patched with tiles and tile roof patched with slate, with occasionally a roof of thatch. [1]

‘Most of these old houses have now been pulled down’, he adds in the 1912 footnotes. Then comes a list of items on sale in the shops:

Scythes, reap-hooks, sheep-shears, bill-hooks, spades, mattocks, ropes and plough-harness at the saddler’s; carts, wheel-barrows, and mill gear at the wheelwright’s and machinist’s; horse-embrocations at the chemist’s; at the glovers and leather-cutters, hedging gloves, thatcher’s knee-caps, ploughmen’s leggings, villager’s pattens and clogs. [2]

These vignettes are extracted, with permission, from The Wessex Project: Thomas Hardy, Architect by Kester Rattenbury, published by Lund Humphries, available here. You can find the first series of vignettes here.

Additional thanks to Toucan Press for the use of Hermann Lea material.

Notes

The Wessex Poems

- Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 1997), p.390.

- Letter to F. Henniker, 22 September 1898, in Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook, pp.390–400.

- Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook, p.391.

- Letters ii, p.212; Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook, p.391.

- Ibid.

- Letters ii, p.214, pp.153–154; Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook, p.392.

- Pamela Dalziel, Thomas Hardy’s ‘Studies, Specimens &C.’ Notebook, p.390.

- John Ruskin, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1849; 1889), p.189.

- Keith Wilson, ‘Hardy and the Ethics of Looking’, The Hardy Society Journal, vol.7, no.1, Spring 2011, pp.38–48.

- Bernard Tschumi, The Manhattan Transcripts, 1976–1981, accessed 4 October 2017.

- Jo van den Berghe, PhD, RMIT 2012; Riet Eeckhout, PhD, RMIT 2015 etc.

- Linda Shires (2015), p.199.

Hermann Lea

- Simon Gatrell, in Norman Page (2000), p.244.

- Michael Millgate, Thomas Hardy: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), p.422–3.

- It is thought Hardy was emulating the New York Editions of Henry James’s novels, but Hardy had always directed his illustrators, and he was certainly no stranger to photography.

- These are full-length films: London, 1994; Robinson in Space, 1997.

The Mayor of Casterbridge

- Thomas Hardy, The Mayor of Casterbridge (London: Smith Elder & Co, 1886), p.33.

- Ibid.