Behind the Lines 7

Mr. Tassie’s House

On June 27th 1807 William Tassie scratched his long nose, dipped a pen in the inkwell, and finished off his letter to Alexander Wilson Esq of Messrs. Dunlop & Wilson, Booksellers of Glasgow: ‘I have been near a twelve month engaged with alterations in my house – which have taken up much of my attention – I have given over modelling portraits, and now confine the front shop to the Sale of Gems. I am Dear Sir, Your much obliged servant…’

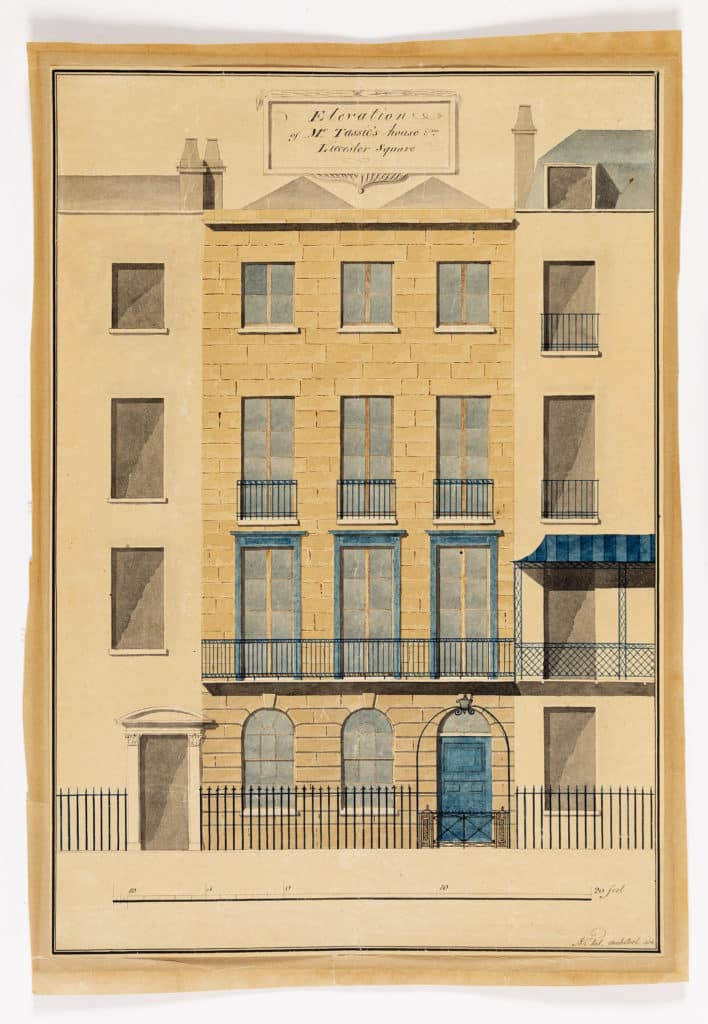

He gazed with pleasure at the drawing Mr Tod had presented for the proposed work no. 20, Leicester Square. The building was updated just as he had wished with floor-length sash windows and a continuous ironwork balcony. William had decided against a fashionable canopy balcony like the house next door – too fancy. He was vastly pleased with the new lamp to shed light on the front door, and the gate ornamented with a Greek key that when open would indicate Tassie’s as ready for business. The first floor was no longer a workshop, as it had been in his uncle James’s day, but had become a salon frequented by his literary and artistic friends who dropped in for enlightening conversation and gossip.

The house still held the secret of James Tassie’s ‘pastes’ – some translucent, some opaque, coloured like semi-precious stones and marbles. That had not changed. So realistic were Tassie’s reproduction cameos and gems that antiquaries had sometimes mistaken them for genuine objects of antiquity. Eight years after his death he still missed his uncle, to whom he owed almost everything.

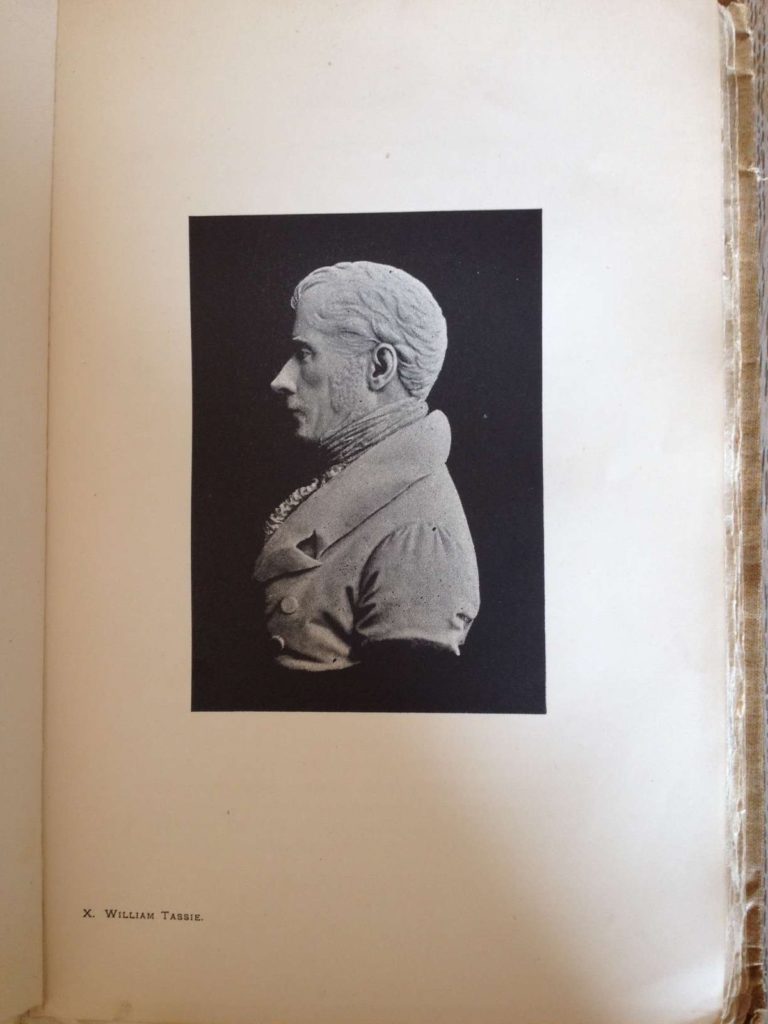

It was, William reflected, a relief to give up struggling with portraits and concentrate on the gems – his skills had never been a patch on his uncle’s – people had flocked through the door of No. 20 to commission a portrait cameo by James Tassie: physicians, admirals, bishops, dukes, baronets, philanthropists, professors, antiquarians, statesmen, diplomats, actors, natural historians, composers, bankers and surgeons, some with wives and daughters in tow. They would decide to be portrayed either in the antique style with their profiles rising above toga-like drapery, or in their own garb. James would meticulously model their profiles in wax and then make two casts with his paste formula to create a bas-relief. As a young man he had been dazzled by the celebrated figures that had sat for his uncle: Horace Walpole, Adam Smith, David Hume, Joseph Banks. It was always the same procedure: 3 sittings, the first two about an hour each, and the third half an hour. Unfailingly, between the hours of 12 and 4 his uncle was to be found in charge of the shop at street level. William had always been mystified at how James could capture such a verisimilitude while the sitters ate or wrote letters – as they so often did. For his part, he needed total stillness to achieve even a reasonable likeness.

It was so much simpler when you could just do a portrait by copying a print like the one he had modelled of Nelson. The outcome of Trafalgar had resulted in a frantic rush for Nelson cameos since it seemed every jeweller in the land had urgent orders for mourning rings and brooches. The workshop had produced little else for several months.

He had propped Mr Tod’s drawing against a pile of unsold copies of the large quarto volumes that both daunted and impressed him: his uncle’s life work. ‘A Descriptive Catalogue of a general Collection of Ancient and Modern engraved Gems, Cameos as well as Intaglios, taken from the most celebrated cabinets in Europe: and cast in coloured pastes, white enamel, and sulphur by James Tassie, modeller. London M,DCC,XCI, printed and sold by James Tassie, no. 20 Leicester-Fields; and J.Murray, Bookseller, no.32 Fleet-Street.’ Inside were listed 15,800 reproductions of Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Arabic, Persian and Modern gems. He recalled the dramatic day when an order had arrived at No. 20 from the Empress Catherine of Russia for a complete set of his entire collection, to be arranged in specially made cabinets, and shipped to her palace at Czarsko Zelo. As Rudolph Raspe, who had toiled over the catalogue, pointed out ‘no care, attention, expense and external ornament was spared that could make it worthy of the patronage of the Great Princess, who had been graciously pleased to order it… ‘

However in one important matter he didn’t owe anything to his uncle – money. How astonished James would have been to see No 20 in its new-found glory, and even more to know that he, William, had also taken the lease of a new house 8, Upper Phillimore Place, Kensington, and that for the first time in nearly thirty years a Tassie would no longer live over the shop.

By what spin of the fortune’s wheel was it that in January 1805 he had run into an impoverished artist acquaintance who had implored William to relieve him of a three-guinea ticket for the Shakespeare Lottery? He had obviously visited John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery in Pall Mall during its heyday and artistic circles had been rife with gossip over Boydell’s bankruptcy problems – he blamed it on the war – opinions differed: his Shakespeare prints were no longer of the finest quality. He had known of John & Josiah’s parliamentary petition to discharge their debt by selling their collection and premises with a lottery. Twenty-two thousand tickets were printed. William won the main prize and found himself in possession of all the paintings commissioned by Boydell: Hogarth, Fuseli, Romney, Reynolds, West to name a few, such astonishment. History painting with its grand gestures hadn’t appealed to William, bought up, as he had been, with miniature antiquities and portraiture. He had sent them straight round to Christie’s.

What a pleasure it had been to have £6,181,18/6d in hand. Notwithstanding a generous gift to his artist friend there had been little problem in paying for every improvement that the worthy Mr Tod had proposed. And then there were the bucolic pleasures of Kensington to look forward to…

– Philippa Lewis