The City of Design

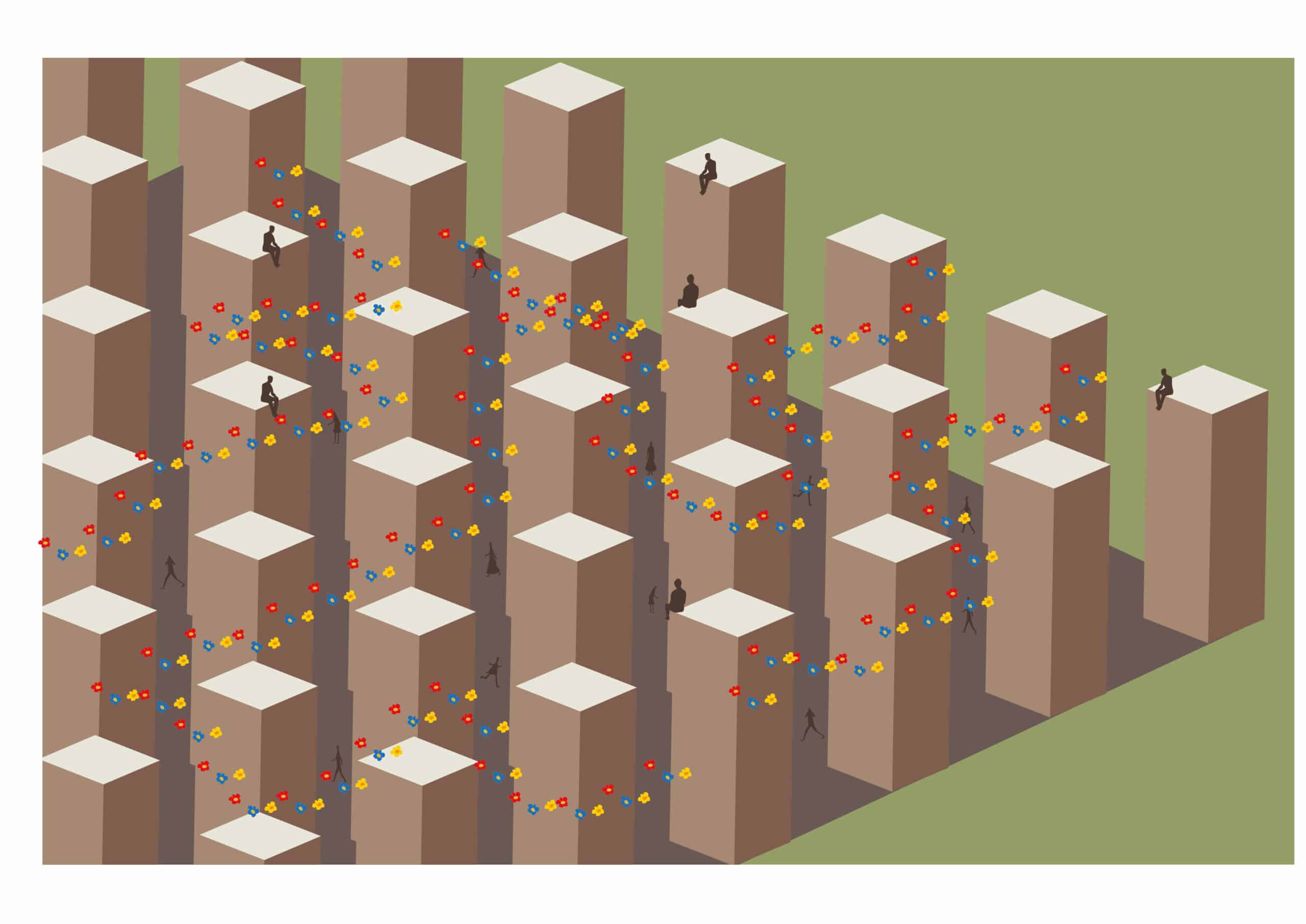

Italy has remained a federation of city-states. There are museum cities and factory cities. There is a city whose streets are made of water and another where all streets are hollowed walls. There is a city where all its inhabitants work on the manufacture of equipment for amusement parks, a second where everybody makes shoes, and a third where all the dwellers build Baroque furniture. There are many cities where they still make a living by baking bread and bottling wine, and one where they continue to package faith and transact with guilt. Naturally, there is also one city inhabited solely by architects and designers. This city is laid out on a grid, its blocks are square, and each is totally occupied by a cubic building. Its walls are blind, without windows or doors.

The inhabitants of this city pride themselves on being radically different from one another. Visitors to the city claim, however, that all inhabitants have one common trait; they are all unhappy with the city they inherited and moreover, concur that it is possible to divide the citizens into several distinct groups.

The members of one of the groups live inside the building blocks. Conscious of the impossibility of communicating with others, each of them, in the isolation of his own block, builds and demolishes every day, a new physical setting. To these constructions they sometimes give forms which they recover from their private memories; on other occasions, these constructs are intended to represent what they envision communal life may be on the outside.

Another group dwells in the streets. Both as individuals, or as members of often-conflicting subgroups, they have one common goal: to destroy the blocks that define the streets. For that purpose, they march along chanting invocations, or write on the walls words and symbols which they believe are endowed with the power to bring about their will.

There is one group whose members sit on top of the buildings. There they await the emergence of the first blade of grass from the roof that will announce the arrival of the millennium.

As of late, rumours have been circulating that some of the members of the group dwelling in the streets have climbed up to the buildings’ rooftops, hoping that – from this vantage point – they could be able to see whether the legendary people of the countryside have begun their much-predicted march against the city, or whether they have opted to build a new city beyond the boundaries of the old one.

CODA

The legendary people of the countryside are coalescing, as of late, into a veritable hinterland. Understandably enraged against the Metropolis, they follow opportune leaders promising them a future made up of yesterdays and of cities returned to green fields and pasture grounds. In light of this, it is legitimate to wonder if the Metropolis, most skillful at surviving, will not adopt those guises the hinterland longs for. The members of the Metropolis, their smoking suits under coveralls, have been seen lately trying to metamorphose their buildings by placing planters and flowerpots on some of their balconies.

Extracted with kind permission from Raymund Ryan’s The Fabricated Landscape, a catalogue that accompanied an exhibition of the same name at the Heinz Architectural Center at Carnegie Museum of Art (26 June 2021– 17 January 2022).

– Peter Sealy