E. S. Prior’s Architectural Modelling

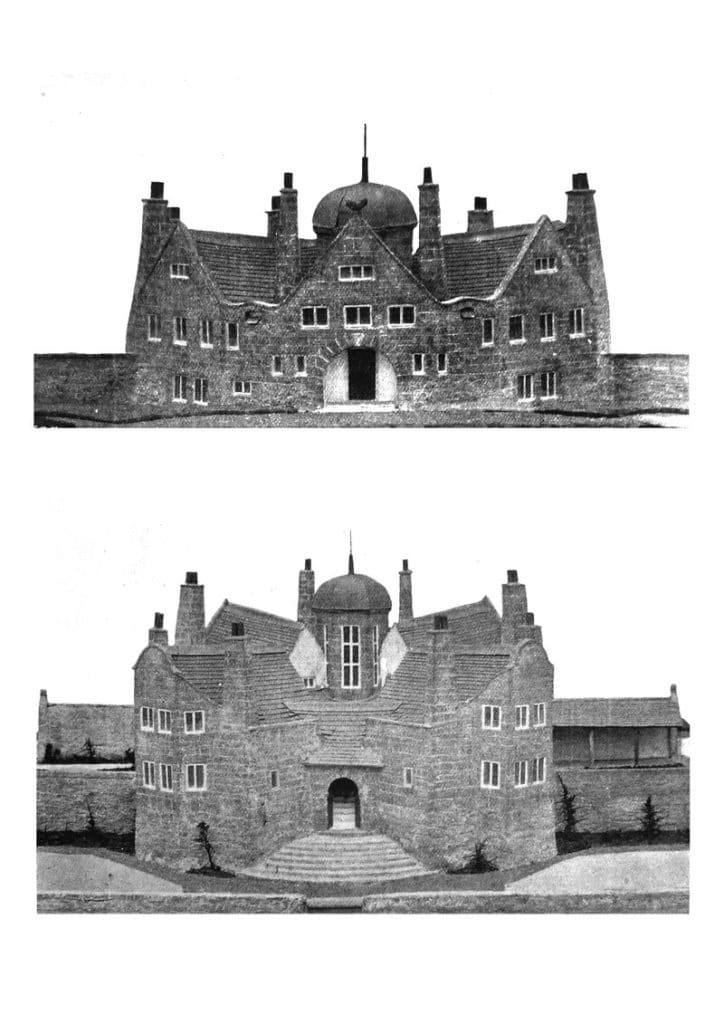

The very fact that The Builder should publish an article explaining the benefits, the uses and the methods of making architectural models indicates just how novel the concept was in 1895, even in theory. ‘Architecture Modelling’ was the result of the almost unprecedented display of an actual model at the Royal Academy Exhibition, ‘the greatest public success of [Edward Schröder] Prior’s career’ and the cause of quite a commotion amongst the architectural press. [1] Over the previous twenty-five years only three models had been exhibited at the Academy: two were shown ‘on an exceptional occasion’ in 1874 by William Burges presenting his design for the decoration of St. Paul’s, and six years later, E. J. Poynter displayed a segmental model of a sixth of the dome of the same church to portray another scheme of ornamentation. [2] No wonder then that a model of an unbuilt design for a small house, made by the architect himself from wax, turpentine and sand, caused the furore it did.

Prior’s model was accompanied by another, of an already built chapel at Tyntesfield by Sir Arthur Blomfield. The reviewer from The Building News, most uncomplimentary about the majority of drawings on display, was quickly drawn with an almost audible sigh of relief to these novelties.

‘The most notable feature in the gallery is one which is very welcome — viz. the introduction of models. This year there are two. One is of a quaintly-conceived country house covered with green-glazed pantiles made in Suffolk for the architect, Mr. Edward S. Prior, who certainly has produced a very picturesque addition to relieve the monotony of the Architectural room. Although this wax model only represents a comparatively small house, it well deserves the conspicuous position assigned to it. We hope this change will inaugurate a more catholic view of things at the Royal Academy. The second model is an ordinarily-produced and very neatly-made one shown by Sir Arthur Blomfield… The model is made in white cardboard and is very hard-looking.’ [3]

The following day, The Builder’s reviewer was so excited by the models that he insisted on discussing them first.

‘The Architectural Room this year contains two models of buildings, in addition to the usual drawings. What may not be hoped from such an innovation? It is true that if this new movement is carried much further, and other architects besides the two bold innovators take encouragement to enter on the same path, the small room devoted to the representation of architecture will soon become inadequate for its purpose; the sooner the better… the innovation is an encouraging one. Though the two models in question do not represent the most important buildings illustrated in this year’s show, we feel bound to give them precedence.’ [4]

Perhaps slightly more complimentary about Blomfield’s model than The Building News, describing it as ‘an example of the highly finished work of the professional modeller’, complete inside and out ‘with the same minute care’, it is nevertheless Prior’s offering which is lavished with the fullest praise, being ‘about as complete a contrast to the first named example as could be’. [5]

‘It is comparatively rough in appearance, and revolutionary in its tendencies. We do not like to suggest anything so much below the dignity of ‘professional’ architecture, but we strongly suspect Mr. Prior of having made the model with his own hands. He is quite capable of it… It is a most interesting and original exhibit and one that is likely to materially aid in rendering the Architectural Room more attractive to visitors than it is generally supposed to be.’ [6]

The unalloyed delight notable in the press’ reception of these models was, however, not shared by the profession. Throughout the weeks of the exhibition and after it, The Builder devoted copious space to the letters from architects complaining about the manner in which the Academy exhibited architecture. The general mood can be gained from F. T. Baggallay’s comments: ‘The people who are satisfied with the present exhibition must be, I think, peculiarly constituted, or entirely pessimistic.’ [7] All agreed that the room was far too small and that few visitors took the trouble to enter it. Most considered the process of selection to be unpredictable if not downright negligent and deemed the Academy’s restrictions on methods of representation misplaced when it came to architecture; demands that gilt frames be dispensed with and photographs allowed were clamorous. Many also voiced severe reservations over the display of drawings that were really the draughtsman’s art, rather than the architect’s. Prior’s letter was predictably scathing on the last point:

‘As amusement the pictures and sculptures [at the exhibition] seem to go down with the public but the architectural exhibit does not. Why should it? What is shown is not the genuine work of the architect, but is only a ridiculous advertisement of it. Everybody knows this, and people do not go out of their way to read stupid advertisements!

The painters and sculptors show their real work, with a seal upon it of personal authenticity, which it would be an insult to question; but as an architectural exhibitor how often have I been asked by my brother architects if I did what I show myself? They know that it is mostly sham performances that the Architectural Room exhibits. What is so well understood amongst ourselves is, of course, appreciated by the public, and they show a wise discrimination in refusing to be interested.’ [8]

The editors of The Builder were unable to let Prior’s first point pass without protest and wrote in response, ‘We think it a very uncharitable remark. In a sense all exhibits are advertisements, and we do not see why the term is to apply to architectural designs more than to any others, or to drawings more than to models.’ [9] This last pointed comment was prophetic, for Prior gained the commission for The Barn (1896–97), one of his most important creations, on the strength of this model.

Beyond the issue of whose art was truly being displayed, the correspondents to The Builder were seriously divided over the matter of how best to represent buildings on the two-dimensional plane, a problem intimately tied up with the question of whom exactly the exhibition was for. For some it was obvious that the public were unable to comprehend technical geometric drawing and that therefore perspectives, drawn or photographed, were the best way of showing a building in the best light. Others insisted that the public would be able to understand plans and sections if they were presented without the extraneous prettifying efforts of the draughtsman. Still others considered it was the profession who were the main visitors to the exhibition and that therefore geometric drawings were infinitely more advisable. Edward Ingress Bell, Aston Webb’s partner, summarised: ‘Is it for the public? Then let it be as pretty and peep-showish as possible. For the profession? Then let it consist of technical work almost entirely.’ [10] Nor was there any consensus over which method of drawing was more true to the realities of the building. As many insisted that perspectives were a truer representation of the building than geometric drawings as argued the opposite case.

Only a few architects mentioned the models that had so energised the exhibition’s reviewers and opinions were mixed. Baillie Scott, too young to remember the earlier models of St. Paul’s, wrote, ‘The introduction of models for the first time this year appears to be a step in the right direction, because they give the real masses and grouping of a building from every point of view,’ [11] and C. E. Mallows insisted that models were ‘the ideal way to illustrate architecture’. [12] Ernest Newton’s praise was more reserved: ‘Well-made models, showing colour and texture fairly represent the building, perhaps; but then the landscape is lacking, and that often determines the character of the house.’ [13] However, F. T. W. Goldsmith considered, ‘my own view inclines to finished sections and plans rather than to models which, at the best, can only be regarded as toys of a kind,’ [14] whilst Baggallay simply proclaimed, ‘I don’t like models; it is a prejudice, perhaps, but there is a sort of dolls-house childishness about them that grates — they seem a waste of time as it were.’ [15] In ‘Architectural Modelling’, printed a fortnight earlier, Prior indeed admits to the ‘doll’s-house naïveté’ of models, but he continues with mock-regret: ‘the method of its presentation can hardly compete with the finesse of the draughtsman, or attain to his easy delusiveness; it must be coarse and frank in comparison, and it is too laborious… And besides… it is really dangerous to show what is so near the truth.’ [16] It is an article that finds Prior at his acerbic best, displaying a now familiar, barely controlled disdain for the professional architect and his drawn architecture, alongside a plea for the rediscovery of material, colour and texture in design.

Two years later, Prior would follow his own advice and use a rough cardboard sketch model for his proposed vestries at All Saints, Margate. At the 1899 Royal Academy Exhibition, Prior exhibited another model for a house design even more striking (some might say awkward) than that displayed four years previously, Walker describing it enigmatically as ‘an ingenious conundrum composed of a pair of diamonds inside a diagonal cross, which is contained within a broken circle’. [17] The Builder commented, ‘The design of the house is of an apparently intentionally naïve kind — what might be called farmhouse Gothic, and the eight tall chimneys, battered in line, standing up at different points, remind one of the towers of San Gimignano. But it is a matter of interest to see a house which is so completely individual and unlike ordinary houses.’ [18]

‘Individual’ and ‘extraordinary’ – how exceedingly pleased Prior must have been.

The immediate legacy of these models and ‘Architectural Modelling’ was a small but significant one. In 1896 a model displaying C. J. Ferguson’s additions to Bamburgh Castle was exhibited at the Academy, though it was given short shrift by the British Architect. In 1903, C. R. Ashbee presented his design for a house on the Cornish coast in the form of a model at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition, and the previous year, Lethaby, Schultz and Wilson’s unplaced concrete expressionist entry for the Liverpool Cathedral Competition had been submitted in the same manner. The latter also included composite photographs of the site and model to give a better idea of the relationship between building and landscape. Not only had Prior made the construction of models by architects a respectable pursuit, but in the longer term he had rehabilitated the idea of the model as a design tool.

Notes

1. Walker, L. B., (1978), ‘E. S. Prior 1852–1932’, PhD Thesis, Birkbeck College, University of London, p. 443.

2. ‘Architecture at the Royal Academy’, The Building News, vol. LXVIII, May 1895, p. 611.

3. ‘Architecture at the Royal Academy’, p. 611.

4. ibid. p. 323.

5. ibid. p. 323.

6. ibid. p. 323.

7. Letter from F. T. Baggallay to The Builder, printed in ‘The Representation of Architecture at the Royal Academy’, The Builder, vol. LXIX, July 1895, p. 25.

8. Letter from E. S. Prior to The Builder, ibid. p. 27.

9. ibid. p. 27.

10. Letter from E. Ingress Bell to The Builder, ibid. p. 25.

11. Letter from Baillie Scott and Seton Morris to The Builder, ibid. p. 27.

12. Letter from C. E. Mallows to The Builder, ibid. p. 26.

13. Letter from E. Newton to The Builder, ibid. p. 26.

14. Letter from F. T. W. Goldsmith to The Builder, ibid. p. 26.

15. Letter from F. T. Baggallay to The Builder, ibid. p. 25.

16. Prior, E. S., (1895), ‘Architectural Modelling’, The Builder, vol. LXVIII, June 1895, p. 482.

17. Walker, (1978), p. 446.

18. ‘Architecture at the Royal Academy’, p. 403.