Summer Evenings on Sukhna Dam

Poornmashi. The bright full-moon nights of the year were always opportunities for us to try to convince our parents to organise a picnic at the Lake.

Chandigarh is a long way from the ocean, way inland, surrounded by the vast Indo-Gangetic plains. And although the mighty Himalayas are right at hand, and there are a couple of intermittent rivers, there is no natural lake anywhere near Chandigarh. As a consequence, Sukhna Lake, realised through the construction of an artificial dam, is especially beloved by the city’s denizens.

In the summer months, after the blistering heat of the day, a cool breeze inevitably picks up in evenings in Northern India, making for an ethos of longing and expectation that is much celebrated, for instance, in Mughal and Rajput poetry and architecture. Mughal Gardens, with their elaborately designed water channels and fountains stand in as metaphors of longed for romances and expectations of better times to come. Near Chandigarh, Pinjore Bagh was a great example of a small natural stream that was exquisitely choreographed into a multi-level lush landscape, described in literature as an embodiment of the Garden of Paradise.

For us Chandigarh kids, thanks to the lack of affordable air-conditioning in India in the 1970s, cool summer nights offered up the prospect of running around town, meeting up with friends and sneaking into dark corners with loved ones. Sukhna lake was one of our especially popular late night hot spots. Its low lighting, and long berm, made many a site that offered reasonable seclusion, without isolation. The cool breeze and the spectacular view made everything seem so perfect.

Before Chandigarh was created, two intermittent rivers used to converge where the Lake is now. Once the Chandigarh site was selected, P. L. Varma, the Chief Engineer of the project, quickly realised that a shallow dam could be constructed that could convert the confluence into an artificial lake. Dam building technology was all around in those times—the halcyon years of Nehruvian India—and the engineers took pride in their ability to build them. Big hydro-electric dams were their forte. The Chandigarh dam was going to be easy for them. But it, of course, still required a budget.

At first Varma proposed that the dam could create a perennial water source for the city. This idea was evaluated and found to be unsustainable. Then he proposed it as a public amenity. This idea languished for a while as other more urgent public projects were taken up—the High Court, Legislative Assembly, the Executive Secretariat. One day, in mid-1955, Varma pulled Pierre Jeanneret into his office to get his support for the project. Oral history suggests that Varma was about retire and so he had decided to expend all his political capital on this. Jeanneret was all for it. Together they approached Le Corbusier and got him to sign off on the project. The Lake was going to be in Sector 1, the vast expanse of the all-important Capitol Complex that Le Corbusier held ultimate veto authority over. Their plan was to show up as united front to the administrators and demand that it should be a modern public garden.

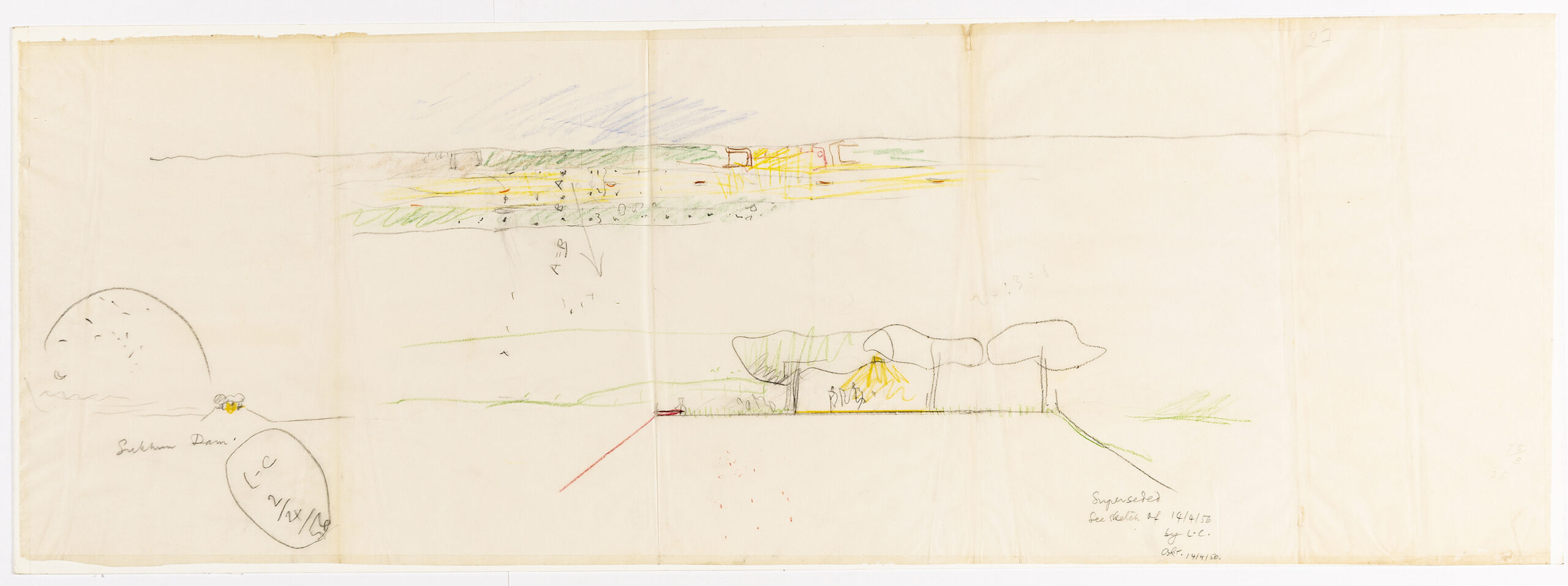

It worked. Budget in hand, Varma supervised the construction of the dam to proceed swiftly. A 1600-metre gentle curve stretched out like an embrace, cajoling the water to stop, to gather. As the lake quickly filled, it formed a beautiful mirror reflecting the adjacent Himalayas. It was breathtaking. Even though it was not his idea, Le Corbusier immediately fell in love with the lake, and quickly took over the reins of designing its architectural details. The dam and lake are like an unexpected found-object discovered on his site of his magisterial Capitol Complex. He rejoiced at the possibilities.

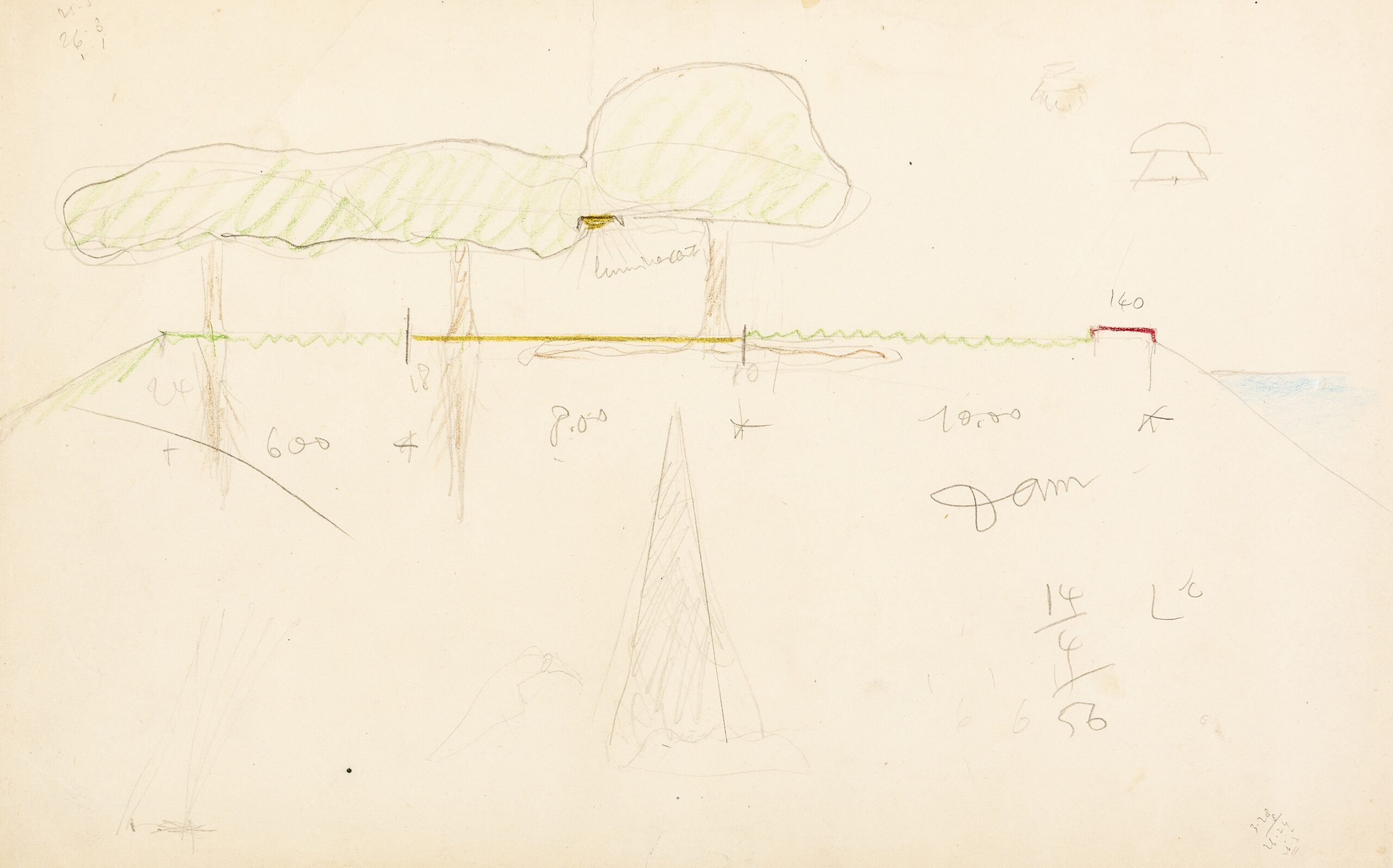

And that is how we find Le Corbusier walking on top of the dam, figuring out how to finish the section. It’s 14 April 1956. The weather is good: no longer chilly and still not too hot. He is trying to decide where to put the walkway on top of the dam. He observes the spillway built by the engineers, and approves. Off to one side he finds a gigantic temporary platform raised on massive load bearing brick piers. This is designed to temporarily hold a huge water tank. His sketchbook (Vol 3, #576) shows him making a note to conserve the structure and add a staircase to it. This becomes a bandstand. Right in front of it, atop the dam he decides to build a commemorative concrete block—embedded into it are drawings made by a donkey driver on the Capitol construction site. Maintaining silence and peace at the Lake is vital for him. At the access point for the walkway he designs a double gate, one side is large enough to let a firetruck through (but blocked by an iron chain to prevent any other vehicles from getting through) and the other one just large enough for pedestrians and cyclists. At one end of the lake he designs a small boat house, a Lake Club. This simple structure, designed to disappear below the eyeline, it is a gem of domino-free plan design, one of the best small buildings in Chandigarh.

But where should the pedestrian path be? Should it be in the middle of the dam with grass on both sides? Or on one side? The latter. How wide should the embankment be? That’s called out in red. And then there is the vital question of the tree cover for shade.

The Le Corbusier drawings in the Drawing Matter Collection show a canopy of trees that would have shaded the entire walkway. Clearly, he was worried most about the mid-day sun, particularly during those terrifying summers. But the planting plan outlined in these drawings is not what was built. Instead, a row of ornamental hedges was planted along the edge of the dam away from the water. These provide some shade, but only in their immediate vicinity. A jogging trail was built along the hedge, which of course was well shaded. I ran that trail, three times a week, every week for years, until I moved to the United States for graduate school. Even now when I visit Chandigarh, my one go-to is to run—well, lightly jog—the Sukhna Lake trail.

But why did they not plant the trees at the top of the dam as the drawing shows? The thing is that Indians have long known how to negotiate the mid-day sun. They don’t step out in it. Everything slows down. Most take a nap. They step out only in the evening, when the sun is below the horizon and the cool breeze blows. No shade needed at this time.

For an evening walk, the Sukhna Lake walkway is the city’s favourite destination. The breeze, the reflected panorama of the Himalayas, along with loud absence of vehicles, makes for a magical environment. The walkway is always packed. People meet and greet with much laughter, folded hands and back slapping. Almost everyone makes it an objective to walk the complete 1600 metres, all the way to the spillway.

As night falls, low lights illuminate the walkway. Most head home for dinner. Some linger, mostly young couples, courting. Eventually they too disappear.

On full moon nights, Sukhna Lake shimmers. My father was a poet. He could recite Urdu poetry—sher-o-shayari—on demand. The Mughals cherished full moon nights. The Taj Mahal is said to have been constructed with translucent white marble with the full moon light in mind. Famous Bollywood lyrics accord to only the beloved a status more beautiful than that of the full moon.

My mother, in my humble opinion, was the best cook in North India. She loved picnics. They signified something like a vacation, a break from the daily grind of the kitchen. She prepared special things for the picnics, particularly on poornmashi, full moon nights on the Lake.

*

Dr Vikramaditya ‘Vikram’ Prakash is an architect, architectural historian and theorist. He is Professor of Architecture at the University of Washington with Adjunct appointments in Landscape Architecture, in Urban Design and Planning and in Digital Arts and Experimental Media. He is also a Member of the South Asia Programme in the Jackson School of International Studies. His recent publications include Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh Revisited: Architecture as Future Preservation and One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash. His first novel entitled Death of a Modernist is due to be published in early 2026.

– Vikramaditya Prakash