Viollet-le-Duc: Ruins in Reverse

In 1844, architect Eugéne Viollet-le-Duc won a competition to supervise the restoration of the Notre-Dame Cathedral.

Blasted and defaced during the Revolution, the condition of the great church testified less to the promises of an infant republic than to the bloody throes of its birth. For its restoration, the Comité des Monuments Historiques required a combination of architectural originality and restorative reverence; a vision that looked forward and backward at the same time. On all fronts, Viollet-le-Duc delivered.

His crowning achievement was the Cathedral’s new spire, a structure that has become etched in our collective cultural memory since its loss in the 2019 fire.

I’m interested in one of the less familiar features of that spire – the patinated congregation of the twelve apostles that stood at its base. Of these, the most intriguing was Saint Thomas. Looking beyond the spire and into the heavens, the statue held in its right hand a draughtsman’s aid. The left hand, meanwhile, was raised contemplatively – the contemplation, it seemed, of a custodian.

The resulting impression was of the apostle reflecting, slightly awestruck, on the satisfaction of a vision realised. To the discerning observer, it was clearly less a representation of Saint Thomas than it was a statue of Viollet-le-Duc himself: a slightly sacrilegious stowaway among the disciples. Looking at a photograph of the statue now (thankfully, removed for restoration just days before the Cathedral caught fire) it is tempting to see, at the same time, an uncanny look of trepidation.

With the gaze of the statue, Thomas’s doubt is recast as the doubt of the architect: a gaze that beholds the improbable presence of the spire and the vacancy of the sky above it and draws, between them, a troubling affinity.

As an expert in restoration, Viollet-le-Duc was necessarily an expert in impermanence.

When he sketched a tropical ruin during one of the meetings of the Société des Antiquaires de France and the Comité des Monuments Historiques, I imagine he sat with a similar time-struck expression on his face, unable to fantasise about the faraway without, at the same time, thinking of the ultimate fate of buildings.

Despite his renown in the field of architectural restoration, Viollet-le-Duc was known for his resistance to inherited wisdom. I doubt he was very partial to meetings.

The committees in which he produced such a considerable body of designs and doodles had the authority to approve, and in some cases deny, the passage of the architect’s drawings into material existence. There he discovered which of his draughts were to be selected for apotheosis, and which were to remain consigned to paper, like ruins in reverse.

It seems to be that Viollet-le-Duc produced two types of drawing during the meetings – the doodle and the design.

At their extremes, a doodle is the opposite of a design. A distinction that is as arbitrary as the distinction between feeling and thinking. With a doodle, each line made on the paper marks the light logic of a feeling. Say, for example, a feeling of lassitude, or a vague feeling of yearning. The end of one line either suspends or renews the feeling, which is what the hand follows, or not, into the next line. A design, on the other hand, is guided by some sort of visualising thought, which may be modified as an inevitable part of the drawing process, but which is more or less rationally guided.

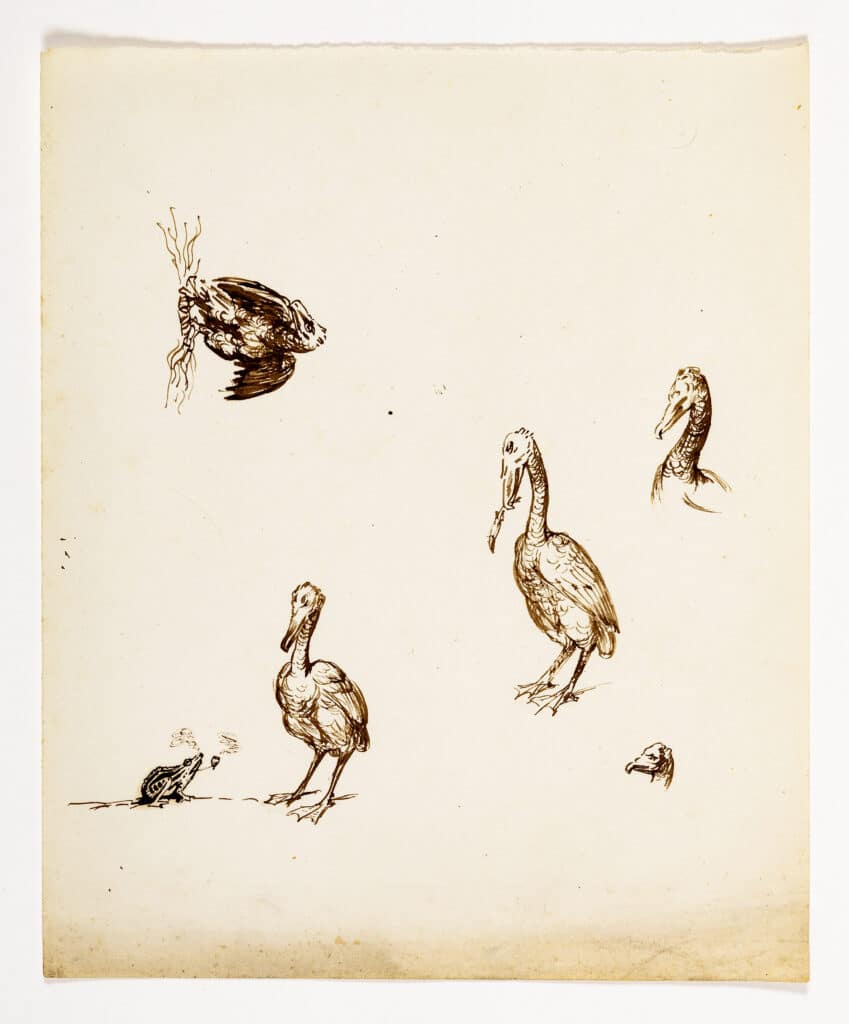

It goes without saying that this distinction is blurred on Viollet-le-Duc’s sketchpad. The mind – with its geometric precisions and its arbitrary wanderings – is laid bare. Precise draughts of flying buttresses accompany flights of whimsy: sketches of animals, a bullfight, a haughty seabird, and daydreamed doodles of idylls and landscapes. A sketch of a neo-Gothic gable end is a few sheets away from an anthropomorphic frog.

We can only imagine what happened in the meetings. Some of the lines suggest a hastiness, a distraction: the urgency to realise on paper a fugitive mental image before it disappeared – hastened perhaps by the pressure of committee proceedings.

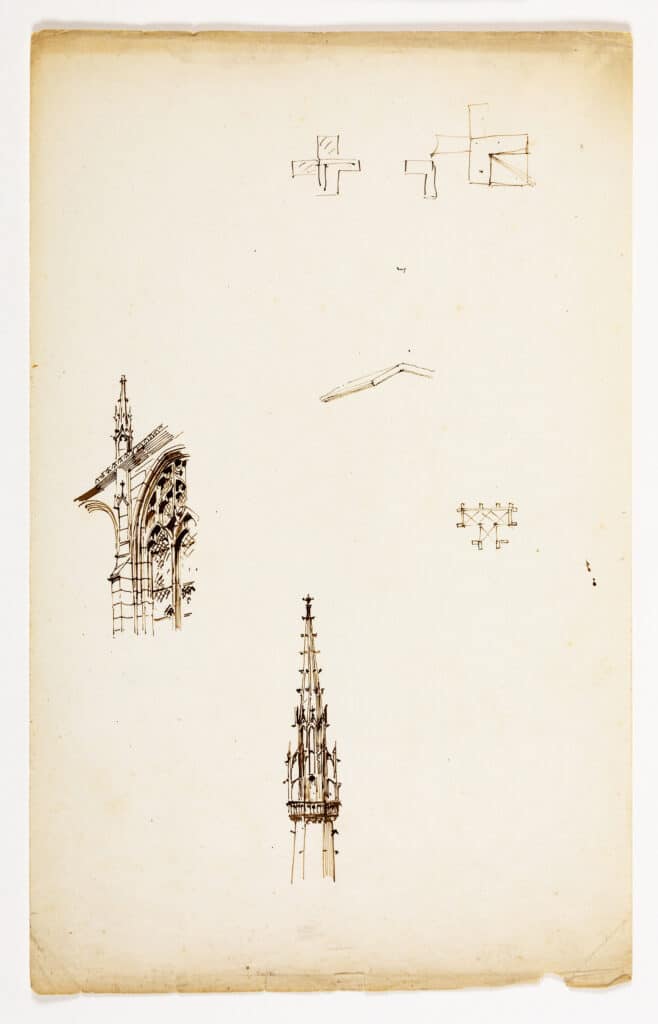

On one sheet, Viollet-le-Duc has made a few attempts to render, from different angles, a gable end. They hover around each other like thoughts. One has been scribbled out. The draughtsman’s careful attempt to render three dimensions on paper is suddenly flattened by this skittering line.

Like all doodlers, Viollet-le-Duc appears to have had his unaccountable tendencies. There is a recurrence of seabirds.

The act of doodling and the act of viewing doodles have a lot in common. Viewing doodles, the mind wanders associatively. It makes irresponsible connections and speculations and adds areas of shade and colour to chanced shapes. It starts sentences with the word ‘perhaps’. Doodles invite us to speculate on the circumstances of their creation to the same extent that they thwart such speculations. They compel thinking in strange and unlicensed ways.

When I doodle, I almost always doodle eyes. Sometimes, a face resolves outwardly from the eyes, like a culture in a petri dish. At this point I will usually move onto another motif – say, a tree (my repertoire is limited) so as to break the sequence and protest against my hand’s repetitive compulsion.

The smoking frog is a version, I think, of this – the kind of drawing, which I suppose is all drawing, that comes from a frustrated will to picture something else (like the elsewhere of Viollet-le-Duc’s ruined tropic). The ludicrous frog, stolidly smoking a pipe, sits firm, as if to say: that’s enough of those birds. If drawing is a gesture, it is often one of a very inconsequential protest.

Fragments, glimpses of Notre-Dame: not the spire itself, but one of its spirelets, with some workings.

These partial drawings, though necessary, nevertheless suggest a recoiling at the thought of the whole. As though drawing the whole might somehow betray it, or pre-empt it, or subvert a natural order. Surviving draughts of the spire, as with any draught of a lost or ruined building, impart a feeling of frail pathos. An image of what was to become becomes an image of what was.

Perhaps we call a building a building – rooting the object in the verb of its conception – to remind ourselves that it is the product of finite action and that it too, as the action, will end. Perhaps we call a meeting a meeting for similar reasons, and happily so. Perhaps drawing drawings, especially in meetings, is a way of living endings.

Thomas Gould is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in Literature at the University of East Anglia.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.

– Martin Bressani