Startha Éagsula: Níall McLaughlin Architects on Basil Spence

This text has been excerpted from Startha Éagsula / Alternative Histories (2020), a companion catalogue to Alternative Histories (2019) and published to accompany the third installation of Alternative Histories at the Irish Architectural Archive.

Startha Éagsula / Alternative Histories is now available to purchase from Drawing Matter’s bookshop, here.

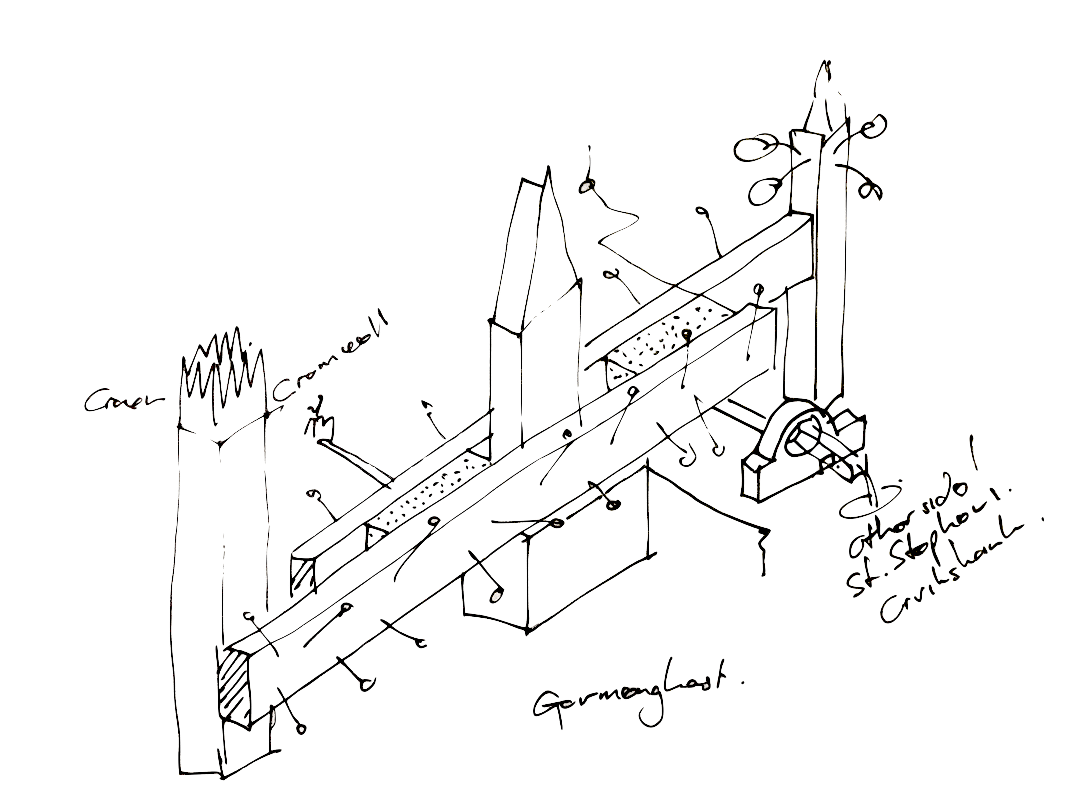

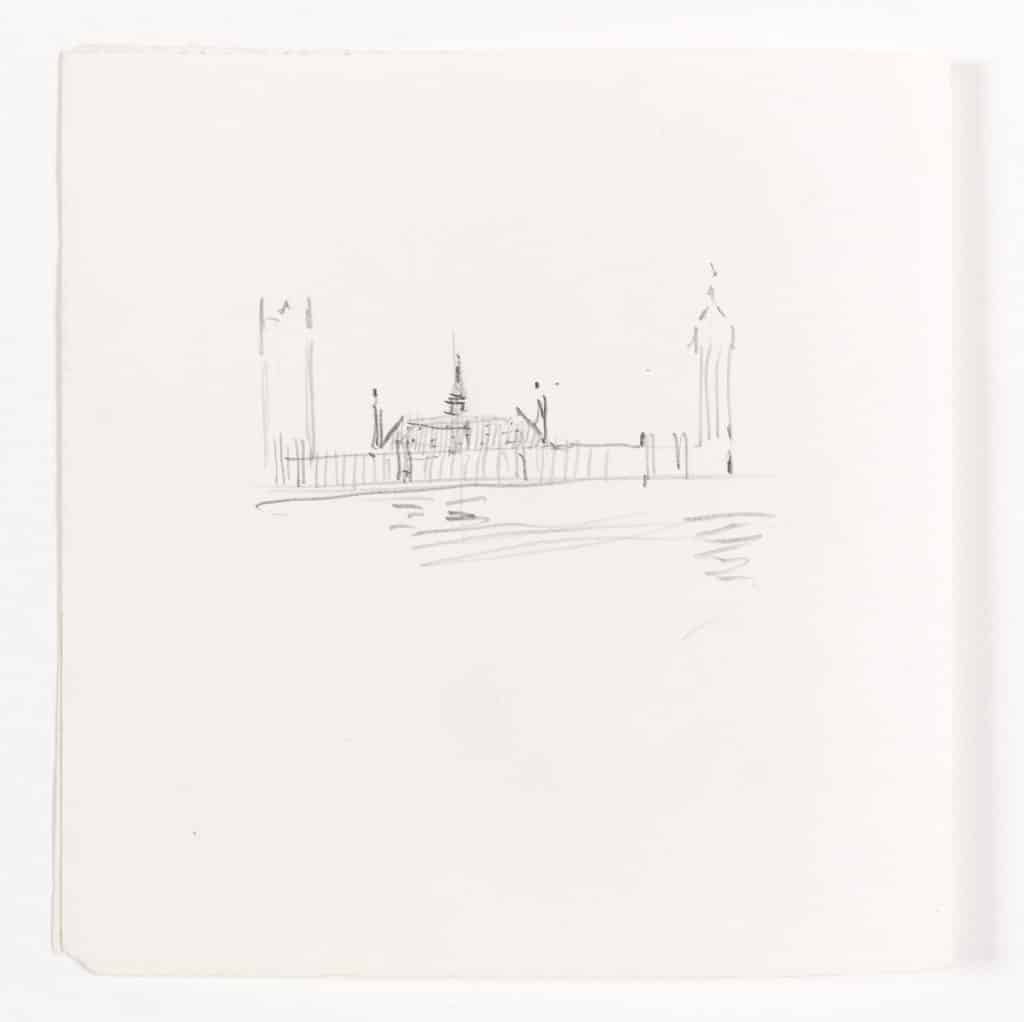

The drawing is a pencil sketch made at a meeting of the Royal Fine Arts Commission in 1969 by Sir Basil Spence. It appears to depict a substantial steep roof mounted on top of the Houses of Parliament to provide additional accommodation for MPs. The roof sits symmetrically over the long river elevation and the existing spire of the octagonal crossing is centred behind it. Regular dots on the sketch of the roof presumably indicate apertures for light and air into the offices. The manner of the sketch is wan and tentative. The rooftop addition appears very large, yet somehow ingratiating and deferential. It suggests an exercise in contextual shoehorning. The drawing should be compared with sketches and proposals made by Spence for the extension to the New Zealand Parliament Building in Wellington at around the same time. By contrast, his work there displayed a hearty indifference to the existing historic context.

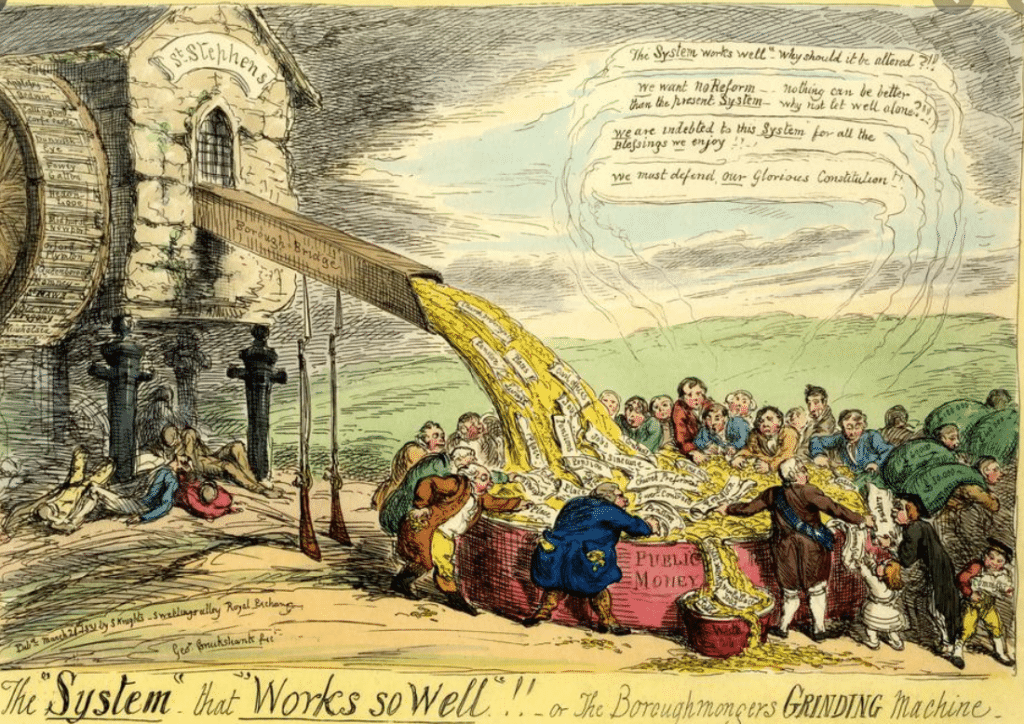

Designed and built between 1835 and 1860, the Houses of Parliament were already a monumental fudge. Charles Barry, the classical architect, paid Augustus Pugin to tart up his competition entry to fulfil a requirement for the building to be in the gothic style. In a time of famines and revolution it was deemed prudent to mollify the country with a reassuring image of tradition and continuity. For Pugin, whose book Contrasts railed against the abstraction and deracination of the industrial age and offered pure gothic as its antithesis, this commission must have felt like an inner betrayal. During design development and construction, MPs mercilessly bullied the architectural team to comply with whims and revisions. It was a brutally pragmatic process where Barry ground out the wishes of the ministers while Pugin sprinkled architectural fairy dust onto this hybrid creature. The combination of realpolitik and delicate fantasy seems peculiarly British.

Gothic revivals are an English business. They embody a yearning for a prelapsarian idyll, a childhood of the national community. English builders were already reviving the gothic manner before it had fully expired and they have been doing it ever since. It is the architecture of innocence and it achieves the primary purpose of all public building: it establishes a fictional temporal depth serving to bind citizens together.

The British Houses of Parliament have been in the world news in recent years. Everyone watched with a degree of schadenfreude as ministers tore each other apart in a gruesome public spectacle. They witnessed the fêted dignity of the British parliament crumble in front of their eyes. The prim, patrician mask was ripped away. We refute the basis of this representation. In contrast, we argue that the visceral bunfight of recent years demonstrates the essence and strength of British politics. Modern principles of communal, democratic representation were hammered out here in a long sequence of similarly chaotic and unedifying spectacles. Laws, as Bismarck would have it, are like sausages, better not to see them being made. When Churchill was offered an enlarged parliament with circular seating after war damage, he declined it, arguing that the House should always feel full, always on the edge of a new drama.

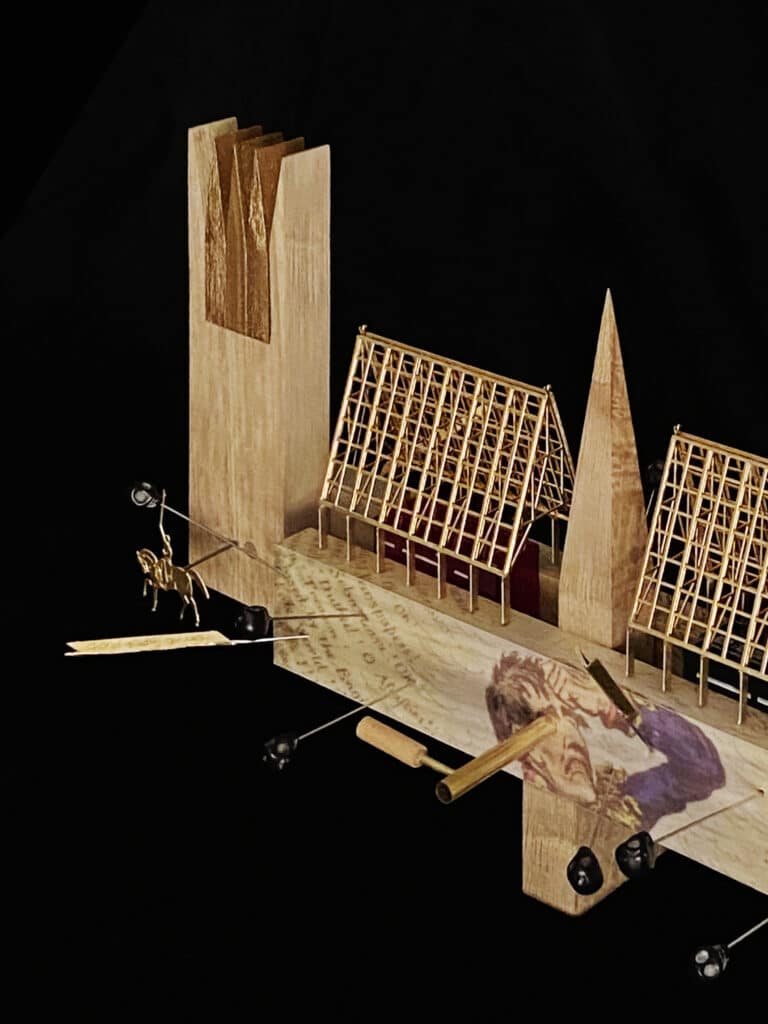

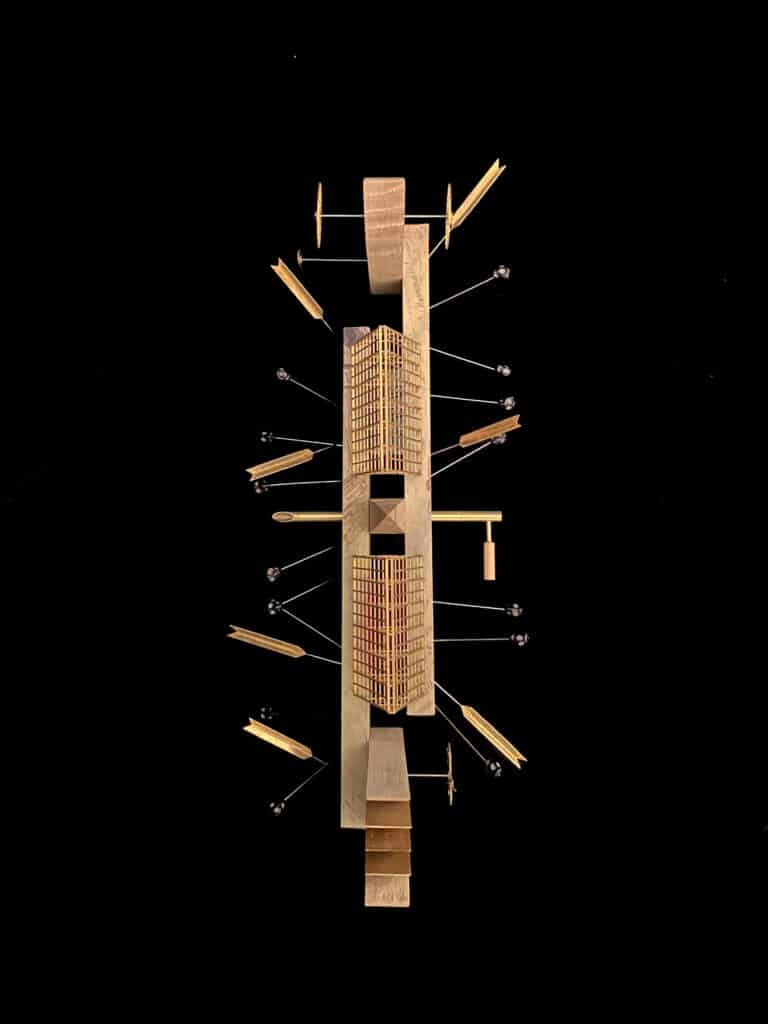

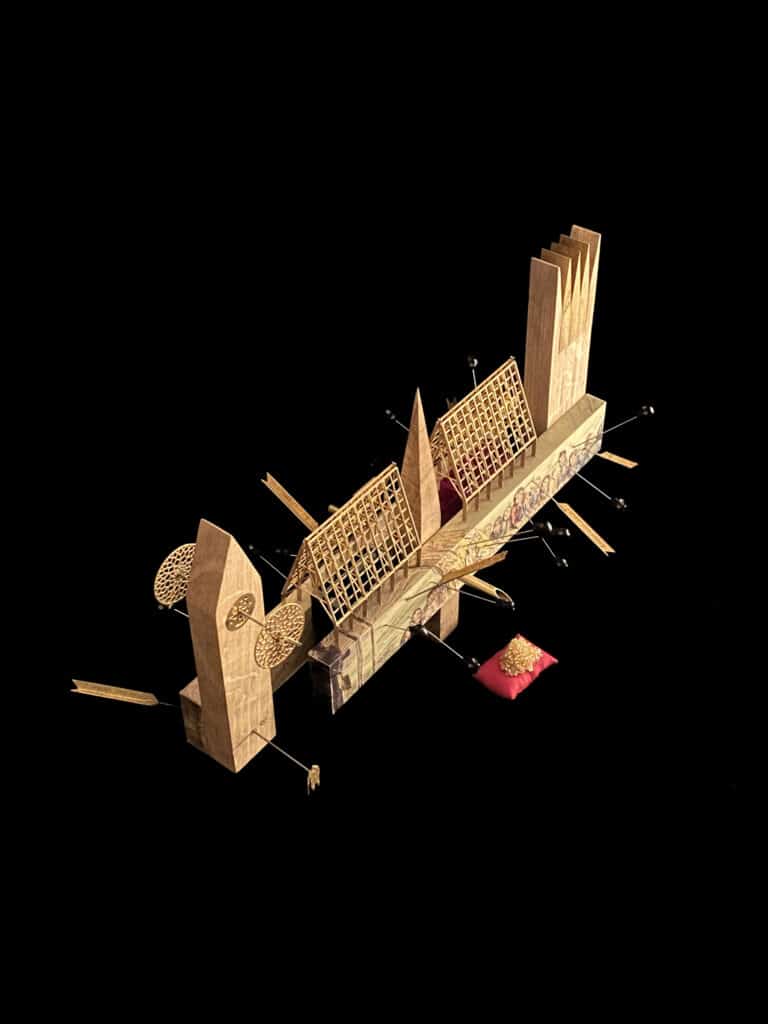

Just as the premature death of the British parliament was being discussed in opinion pieces, the government announced plans to refurbish the Houses of Parliament. This never-new, never-old building was already crumbling away. Our model sees the long refurbishment as public autopsy, or excavation. Like Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp, the peeling back could become an edifying spectacle and a public process. It could be witnessed and contested. We propose a public space on the roof covered in lightweight, interwoven wicker in homage to the putative origins of gothic. When the restoration is finally finished, the wicker cage can be taken down and put on a bonfire along with televised press briefings from the prime minister. Send him back to the House.