Ernest Gimson: Against Hotch-Potch

– Annette Carruthers, Mary Greensted and Barley Roscoe

When Ernest Gimson applied to join the Art Workers’ Guild in 1891 he described himself as a ‘decorator’, and it is clear that interior decoration and furnishing remained vital to him throughout his life as part of his vocation as an architect. His were not the fully coordinated decorative schemes of the aesthetic movement fashionable in his youth, nor of the art nouveau in vogue when his own work came to maturity. Although he did not join in the chorus of public disapproval raised by many of his contemporaries in the AWG he clearly shared their views on the dangers to British design of ‘the New Art’, which was widely feared as a dangerous contagion from the Continent. [1]

In a letter of 1907, advising on the architectural training of his nephew, Gimson wrote of ‘the Baillie Scott & Edgar Wood school of “L art nouveau [sic]”’, suggesting that it ‘of course has qualities but their principles are so opposite to my own that I naturally should not think their influences the best that Humphrey could come under’. [2] His disapproval was primarily based on his view that art nouveau architects had too little interest in the craft of building, but was also connected with attitudes to how much control of the interior should be handed over to the designer. In his own projects he did not expect to coordinate comprehensive decorative schemes, but he suggested wall colours to his clients and prepared designs for suites of furniture to suit particular places, as well as producing items that customers could buy individually from exhibitions or his showrooms.

Because he built relatively little Gimson had few opportunities to design complete schemes and his own cottage at Sapperton is probably the best guide to his ideal of decoration – in the country at least. Whitewashed walls and wide oak floorboards provided a setting for seat cushions and curtains in Morris & Co fabrics, a bold unpatterned hearthrug and predominantly contemporary furniture, including one of William Lethaby’s Kenton & Co armchairs, the wedding-gift Dolmetsch piano and examples of Gimson’s own design. A few pieces of antique wood and metalwork were included and he wrote in a letter to Robert Lorimer that ‘though my furnishings are mainly of new work, one or two old things with pleasant associations have crept in’. [3] The fashion for antique and reproduction furniture was very strong at this time and grew to the extent that Lethaby felt the need in the postwar context in 1920 to warn that:

‘the buying of old furniture, the pawnshop ideal of furnishing, has been overdone; it has encouraged dealing and discouraged making. A fine piece of old furniture is, of course, a delightful possession if you have it, or if it “comes to you”, but the right thing now must certainly be the encouragement of living makers; further, you will thus escape the danger of buying sham antiques.’ [4]

His plea on behalf of living makers was no doubt prompted by his long association with Gimson and knowledge of how vulnerable such businesses were to competition from the burgeoning antiques trade.

Some of Gimson’s large-scale projects were for historic buildings where sensitivity to the site was essential and occasional misunderstandings arose from different ideas about what was required. Gimson and William Weir developed a harmonious working relationship and the bridges, doors, benches and display cases made at Daneway in 1913–14 for Tattershall Castle met with complete approval from Lord Curzon, who understood the position of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings on the advantages of installing frankly modern work in historic settings. Tattershall was anyway being rescued from dereliction and consolidated as a monument rather than rooms with a particular function. The new woodwork provided security and an appropriate background for the important carved fireplaces and other architectural features.

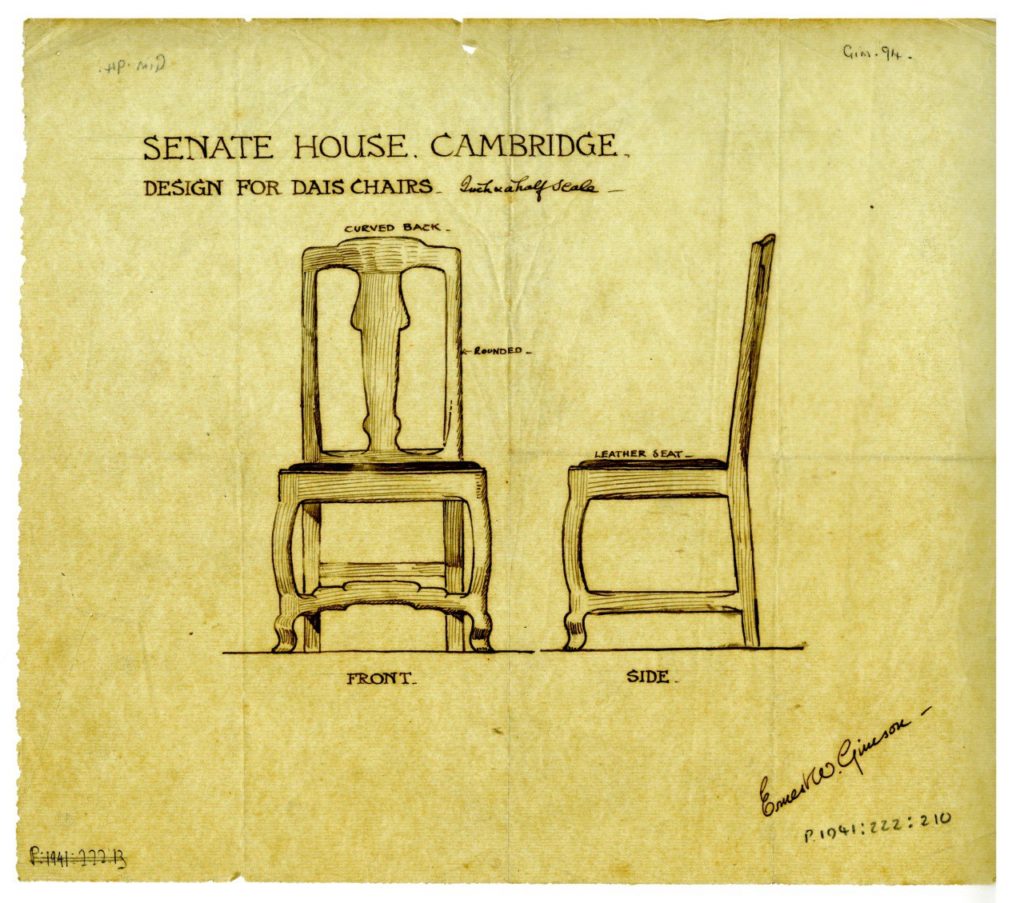

A less happy project was begun for the Senate House and Magdalene College Library in Cambridge in 1916, initiated by Arthur Benson, the diarist, essayist and poet who had recently become Master of Magdalene and embarked on a substantial programme of improvements at the college. Montague James – medieval scholar, author of spine-chilling ghost stories, and Vice-Chancellor of the University – was also involved. This was a difficult time for the workshop, but Gimson sent a sample chair for the Senate House in April 1916 and three for the library in June. Wartime restrictions delayed deliveries as well as affecting staffing. Because time was short he agreed reluctantly that his sample could be copied if necessary by the local cabinetmaking firm of Perry Leach, which had supplied him with plans of the dais in the magnificent James Gibbs classical interior of about 1730 at the Senate House. [5] In July, Gimson sent a detailed ‘scheme that I think would give the most dignified arrangement & the one most suitable architecturally’, and in August he prepared two new designs, but despite his plea that the Senate might ‘recognise the difficulties of these troublous times’, agreement could not be reached. [6]

Benson complained to William Rothenstein that Gimson would not give him what he wanted, ‘only what he thought it right of me to want’, [7] while Gimson explained to Sydney Cockerell that Benson and James had rejected numerous proposals because ‘they don’t follow in detail the style of “the period”, a curious reason for intelligent men & doubly so when both of them are members of the SPAB that exists to oppose that point of view’. [8] He considered he was being asked to make ‘sham antiques’ and wrote:

‘If they want period chairs the best thing would be to buy old ones – at any rate they should understand that it is impossible for anyone to design them – a copy might be made of some old specimen or a hotch-potch of many and called a design – & we both know the folly of it: The only sensible course is to get a good piece of modern work that isn’t unsympathetic to the expression of the building … Benson & James only assume that my designs are unsuitable to the building because they fail to find in them any of those early 18th Century tricks of design that they are looking for.’ [9]

His designs were not reproductions of eighteenth-century style but their curved legs echoed the shaped supports of the benches and cabriole table-legs in the room. One had a solid central back splat of a type found in chairs of the correct period. They appear rather curious by comparison with his usual chairs but would probably have worked better in the setting than the straight-legged, mid-century, Chippendale-style set bequeathed to the university in 1920, which rescued Benson and James from a knotty and expensive problem. [10]

Extracted, with permission, from Ernest Gimson, Arts & Crafts Designer and Architect by Annette Carruthers, Mary Greensted and Barley Roscoe, published by Yale University Press © 2019. Available from YaleBooks.

Notes

- For an account of early twentieth-century British attitudes to art nouveau, see Theiding 2006.

- The Wilson, Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum, 2006.5.120, EWG-SAG, 17 March 1907.

- Edinburgh University Library, 1963/52, file 7, EWG-RSL, 17 February 1919.

- Lethaby 1922, p 43.

- Magdalene College Library, Cambridge, ACB C/ACB/4/iv, EWG-ACB, 27 April 1916. Walter Perry Leach had premises in King’s Parade, Cambridge. For a good account of this building and photographs of the interior see T Friedman, James Gibbs, New Haven & London: Yale University Press 1984, pp 226–32.

- Magdalene College Library, Cambridge, ACB C/ACB/4/iv, EWG-ACB, 17 July 1916. Five related buildings survive: CAGM 1941.222: 206-10; since two of these are for chairs and his letter of 17 July mentions ‘seats’ it would seem that this early version is missing or unidentified.

- Rothenstein 1932, p 275.

- Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, DE 1963/15, EWG-SCC, 16 August 1916 (transcript).

- Ibid.

- In The Reporter, 23 November 1920, the vice-chancellor gave details of the bequest, which requested they be placed in the Senate House.

– Roz Barr, Biba Dow, Elizabeth Hatz, Emma Letizia Jones, Stephanie Macdonald and Helen Thomas