Artists at Work

I recently had the pleasure of jointly selecting a group of drawings from the Katrin Bellinger collection for the exhibition Artists at Work at the Courtauld Gallery, London (3 May to 15 July 2018). The title is generically applied to her focused collection of paintings, drawings, prints and photographs concerned with artists’ academies, studios and workshops, self-portraits and images of practitioners drawing or painting in ruins, gardens or landscapes. As sub-genres within the long-established but still popular genre of celebrating artistic learning and practice, each of these areas evokes complex associations for both artist and viewer. Artists’ self-portraiture, for example, deals with aspects of reflection and reflexivity: the mirror in which the artist captures a likeness while in the act of drawing or painting reflects back professional activity as well as recording an unique personality at a particular moment in time. Representing other artists at work – that is painting another person painting, or drawing another in the act of drawing or taking a photograph – is similarly a reflexive and circular activity. The external spectator of these self-conscious views is both present and excluded while the intensity of the recorded artist at work echoes the preoccupations of the authorial presence as participant in an exchange about the professional value of vision and creativity.

The self-reflexivity of recording oneself looking, making and commenting on art is very different from the vacuous act of simply recording oneself looking at something on a device. Looking is the activity of the twenty-first century that is increasingly processed through a lens: of a still or moving camera, a computer screen or smartphone. But in the ubiquitous ‘selfie’, when the lens records the instigator filling the frame while not looking at the Grand Canyon, the Mona Lisa or St Paul’s Cathedral from which she or he has turned away, the much vaunted scopic truth has been turned into a veritable negation of the gaze. That potent and widely disseminated image of the campaigning Hillary Rodham Clinton in Orlando USA in September 2016 facing a long line of young people with raised arms who have turned their backs on her, lingers in my memory as a visual absurdity with uneasy consequences. By enticing the politician into their greedy frames alongside their own dominant physiognomies, each clone in the audience obliterated her actual presence… in more ways than one, as it turned out.

So it is the interrelated activities of witness, representation and creative invention which are significant in artists’ self-portraits or records of other artists at work. In my catalogue introduction to the exhibition I briefly related this subject to the long Western tradition of the Evangelist St Luke drawing and painting the Virgin and Child. By associating artistic practice with divinity – early Byzantine images of St Luke painting the Virgin achieved mythical status during the Middle Ages – visual art was positioned at the very centre of the Christian mysteries in medieval and early Renaissance times. I tied this theme to related drawings in the Bellinger collection where the topos was re-interpreted in post-enlightenment Europe. For example, my reading of a drawing by the academician and art critic Charles-Nicholas Cochin the Younger (1715–1790) of Saint Luke Painting the Virgin is that the signs of the numinous (clouds of putti and concentration of highlights) have been shifted from the original subject of the holy mother and child as haloed luminaries to the activities of a now secular artist. The figures of a woman and child on the left of the drawing appear to be artist’s models and all the attention of a busy bevy of floating putti acting as present-day emojis are focused around the central canvas held up for the bearded artist at his easel with palette, brushes and mahlstick. Drawn in Cochin’s deliberately anti-rococo manner, the activity takes place in an outdoor space, with a colonnaded façade appearing out of the clouds on the right and a receding pavement for the participants on which is displayed a bold cartouche of drawing and painting implements. Although this celebration of painting demonstrates how art could replace doctrinal religion as the ineffable source of the sublime in the eighteenth century, there was unfortunately no space to develop the argument by including this work in the limited display.

However pleasurably intimate, the small drawings gallery at the Courtauld – like all public exhibition spaces – calls for works that ‘hold the wall’. Drawings in sketchbooks or portfolios and scraps of paper for studio use may be tiny and incidental, but their intimate scale or simplicity of means melt into insignificance when they are directly handled and closely viewed in a spectatorial surrogacy of the original creative process. Fixed on the wall however, a framed or even a simply mounted work assumes a different level of importance, so exhibitions always pose particular problems about juxtapositions, thematics and narrative relationships. In these circumstances, it is not only the powerful and attention-holding drawings that are deemed best for display, but also the ‘important’ works by significant artists. We wanted to show the gems of the Bellinger collection for a diverse audience, but I also hoped to illuminate the many aspects of those representations of practice across a wide historical and geographical spectrum that I had addressed in my book The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice [1]. I insisted on including a number of interesting works by unknown or amateur artists as well as a few representations of women artists, but some delightful little drawings were, regretfully, relegated to a brief mention in the catalogue. All of which brings me to a diversion about graphic humour.

My life experience has taught me that any attempt to write light-heartedly about historical art, or even to point out the perceived humour in an artwork is generally edited out of a text. Humour acts as a red rag to the supervisory spirit of editors, exhibition organisers and academics, and putative amusement calls out prissy and punitive interventionism as a matter of course. (Humour seems to me to be yellow in colour – I would never presume to employ blue language in print! – so the red pencil response, even when only a temporary glitch in an editorial overview, is extremely curious.) Art historians generally assume that artists, unless they are fully paid-up members of the caricatural confederacy (shelved under such a label in a Dewey or Library of Congress catalogue system and conducive to Boolean search etiquette), are never funny or relaxed and that even their patently silly sketches deserve the most solemn explanations. The collapsing of active and passive forms of linguistics seems to be at fault, [2] because to laugh at the ridiculous alongside the artist is not to downgrade the work or ridicule the artist. So the inclusion of ironic works in an exhibition is consistently high risk in that they inevitably call for opposition, and witty labels are total anathema: Joe Public, whom everyone cites and no one has met, just hates them!

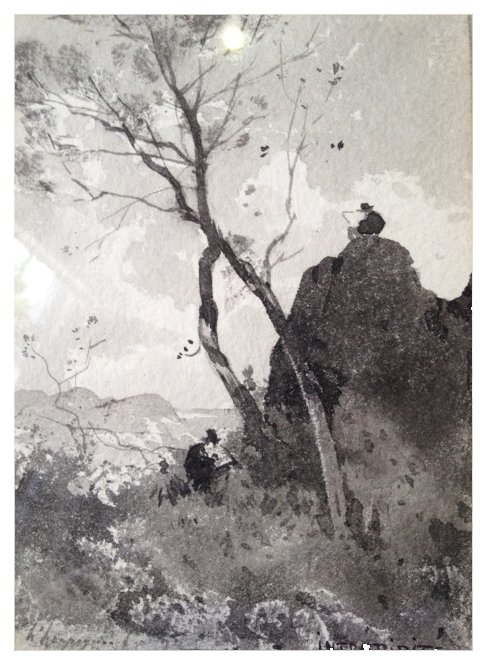

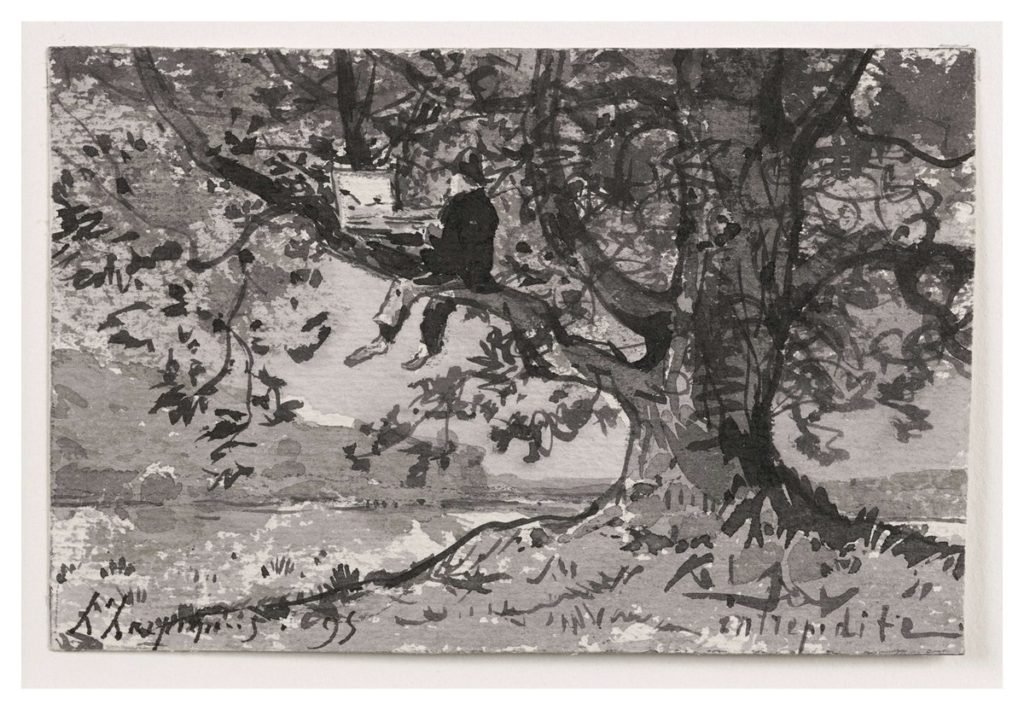

Nevertheless all drawings collections contain serious graphics as well as absurd sketches, which should be happily brought out of the closet like those pornographic naughties of an earlier age that have long been solemnly revealed. So it gave me pleasure to draw attention in the catalogue to two small but delicious ink wash drawings by the French landscape painter Henri-Joseph Harpignies (1819–1916) from the Bellinger collection that gently mock the conditions of drawing en plein air. Harpignies, associated with the Barbizon group of French landscapists that included Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny and his much admired older colleague Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, was accustomed to working companionably with other artists in Fontainebleau. He first visited Rome in the 1850s and returned to Italy, whereas Corot undertook regular Italian pilgrimages together with other artists, drawing archaeological sites and landscape in company with colleagues who were sometimes recorded at work in his sketchbooks. Corot’s use of subtle grey tints and lightness of painting touch surfaces again in Harpignies’ free and delicately gestural late monochrome ink sketches around 1900, in which he sometimes includes brief and playful indications of artists at work or trudging through the landscape with canvases and easels strapped to their backs. In Two draughtsmen in a landscape, he contrasts two deeply absorbed behatted artists, sketched with total economy of means. The lower figure with an enormous drawing board on his lap is visually hemmed in by the rocky hillock on which his fellow landscapist is precariously perched and boldly silhouetted against bright clouds. The question ‘how did he get up there?’ also hangs in the air in the companion drawing A draughtsman sketching on a branch of a tree, with the amused comment ‘intrépidité’ inscribed on the ground below the spreading oak. Somehow this valiant fellow has managed to hoist a canvas and box of paints into the tree. He nonchalantly straddles a huge branch in order to capture the shining river and distant shore in his search for the ‘truth’ of landscape drawn on the spot – even if partly obscured by intruding branches and awkward foliage.

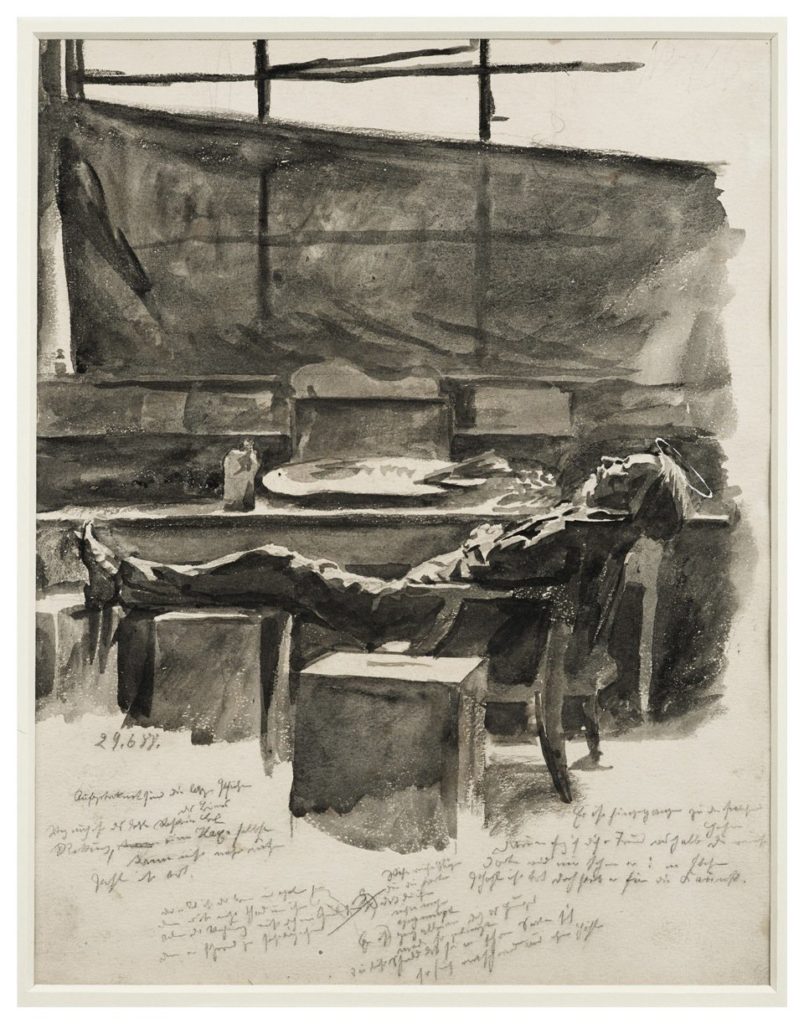

An ink wash sketch with pencilled notes below by the German symbolist artist Otto Greiner (1869–1916) requires no commentary, except to draw attention to the sophisticated rendering by which light from the huge studio window picks up the oversize palette on the table, the profile and crushed clothing of the snoozing artist and the top planes of the studio plinths supporting this pleasurable studio inactivity. These ‘highlights’ are created by leaving the brightness of the paper support to contrast with ink-washed areas, although the precise halo around the artist’s head appears to have been added later in white paint. The wit of this sketch and those of Harpiginies depends as much on drawing skill as the absurdity of the subject.

Working artists have always been – and will continue to be – jobbing hacks as well as great names; amateurs as well as professionals; women as well as men; witty commentators as well as pompous practitioners. ‘Artists at work’ can be a theme of great profundity – but also an enjoyable occasion for a little levity.

Notes

- Deanna Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice, London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- I wouldn’t dare employ the noxious term ‘political correctness’.

– Niall Hobhouse