Behind the Lines 4

Isabella Puddefoot settled herself on the sofa, picked up her embroidery, and after enquiring about his day at the bank, remarked to her husband Samuel: ‘I do declare I am quite spent; running up and down stairs all day is very trying to my constitution. It is eight flights from dealing with cook in the basement to reaching the children’s rooms upstairs. Doctor Golding says I should be preserving my strength, especially with my next confinement due in November.’

There was a pause while Samuel wondered vaguely where this was leading, so he made a noise he trusted sounded sympathetic.

‘Have you noticed, Samuel dear, that the people who have taken the lease on No. 9 next door do not seem at all genteel. I hear he is a grocer and tea dealer on Camberwell Green.’

Samuel grunted that he had not seen them, and turned his attention back to The Times.

‘I paid a visit to Charlotte Bowers this afternoon and she showed me such an exceptionally interesting thing that John is investing in.’

The last two words finally caught Samuel’s attention. He turned to her, eyebrow raised.

‘Fetch that portfolio sitting on my escritoire, I’ll show you.’

Samuel disliked the strain of imperiousness in his wife, but loved her white, sloping shoulders and delicately small hands.

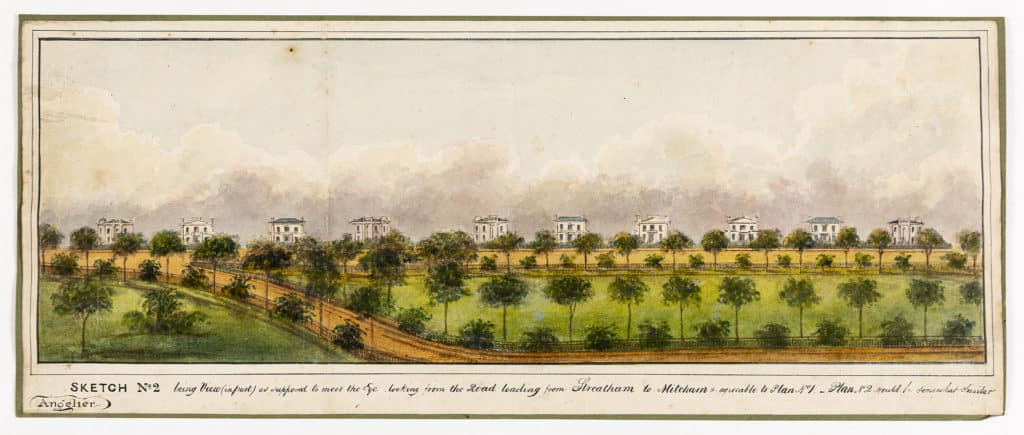

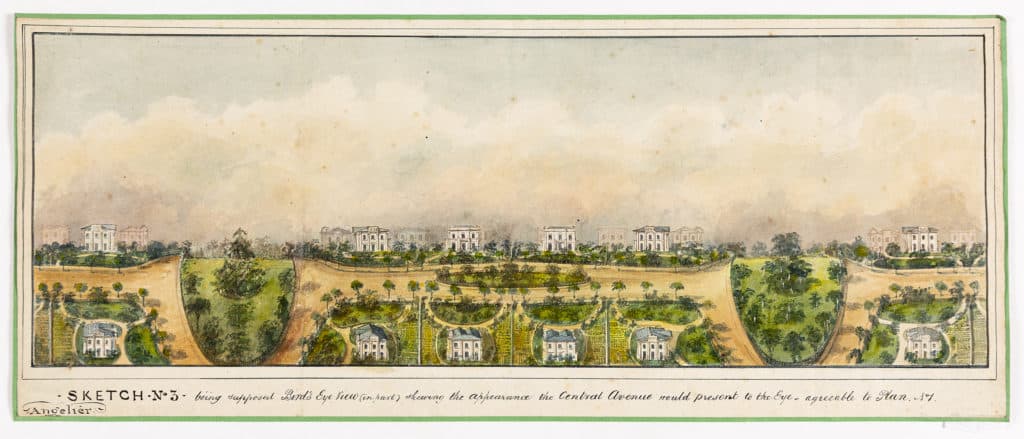

‘Look, Samuel, my love, here are three watercolours of delightful houses that are to be built beyond Streatham. Doesn’t that look excessively pleasant? It is to be called Streatham Manor Park. What a distinguished address! Imagine, it will be like those beautiful villas we saw in Prince Regent’s Park. Charlotte says it is exactly where families like ours should be living, and she, of course, knows because John Bowers has connections in the building trade. She told me that Decimus Burton, the architect of the Regent’s Park villas – whom John, by the way, has met – is planning something similar in Tunbridge Wells, to be called Calverley Park. It will be the most fashionable place; so I am sure Streatham Manor Park will be too.’

Samuel questioned whether the purlieus of Streatham and Mitcham could ever be fashionable – and wouldn’t it take an unconscionable time for him to reach the bank each morning? That it would also be considerably further from the comfort of his club was an objection that he kept to himself.

‘But, beloved Samuel, I have already enquired: the fast coach stops at the Pied Bull on the High Road and will get you quickly to the White Horse in Fetter Lane. Besides, think of the pure air. We would be able to smell the lavender fields of Mitcham – whereas here I know I can smell the Bermondsey tanneries when the wind is in the wrong direction. And the children, think of the children, how delightful for Freddie, Sophia, George and little Esmond to have a garden to play in.’

Isabelle jabbed at the drawing with her elegant little forefinger.

‘I think we should live here, where it says Central Avenue, and look, there is a lake; Freddie could fish, and maybe there would be boating, and I am sure that the neighbours, delightfully not within earshot, would be the most genteel families. Charlotte says that there is an excellent Academy for Boys nearby, and the Misses Pargetter’s school for Young Ladies is renowned for its drawing and dancing masters.’

Samuel peered closely at the pictures and wondered who exactly ‘Angelier’ was. He supposed some poor artist trying to earn a shilling or so by making Bowers’s investment look like a good proposition. Or perhaps he was an underpaid drawing master. He searched for another objection to his wife’s unpalatable suggestion and came up with the tendency of stucco to peel, its glaring paleness and his attachment to good London brick.

‘Yes, Samuel, dear one, but a villa must look like stone, and it is so very superior to a terrace. I so like the idea of a detached house surrounded by garden. We could plant a shrubbery. Some, Charlotte tells me, are in pairs, which are more economic, if less desirable.’

At this point the question of finance loomed into Samuel’s head. He demanded to know whether Isabella had even considered the extra cost. Such a house would clearly need at least two housemaids, as well as the cook and kitchen maid, the nursemaid, a gardener and a gardener’s boy. His daily travel would cost more; new furnishings would be needed and that was without even considering the leasehold price.

‘Oh Samuel, sweetheart, but we have plenty of money, my father settled £1,000 a year on me. Heavens, his business manufacturing steel pen nibs in Birmingham is thriving. There is the bank, and the investments I often overhear you boasting to your friends about.’

Samuel Puddefoot went a shade paler, his eyes shifted towards the window that looked out onto their street and fixed on the sooty rim of the glazing bars. He wasn’t exactly sure how he would admit to Isabella that his investment in that foreign mining company had failed so catastrophically; he would certainly have to delay paying her millinery bill till well into next year. A move to the suburbs, however leafy, was completely out of the question. Perhaps he should have taken Bowers’s tip about the Leasehold Estate Investment Company seriously.