Thomas Henry Wyatt’s Brook House

There is no building that tells the social and aesthetic story of Park Lane better than Brook House.

From its beginnings as a scrappy country lane (‘Tyburn Lane’) in the eighteenth century, Park Lane rose to become the millionaires’ row of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and went on in the 1920s and 30s to become a street of huge apartment buildings, hotels and showrooms. Its current character is global rich with a Middle Eastern flavour. Brook House, in its various incarnations, has followed this trajectory.

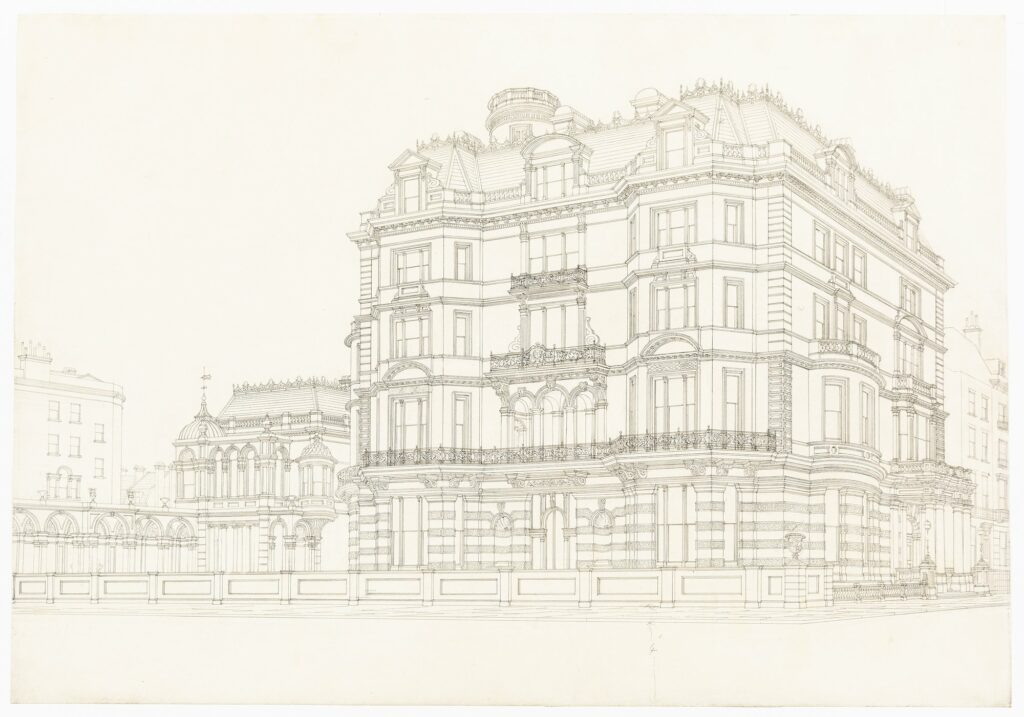

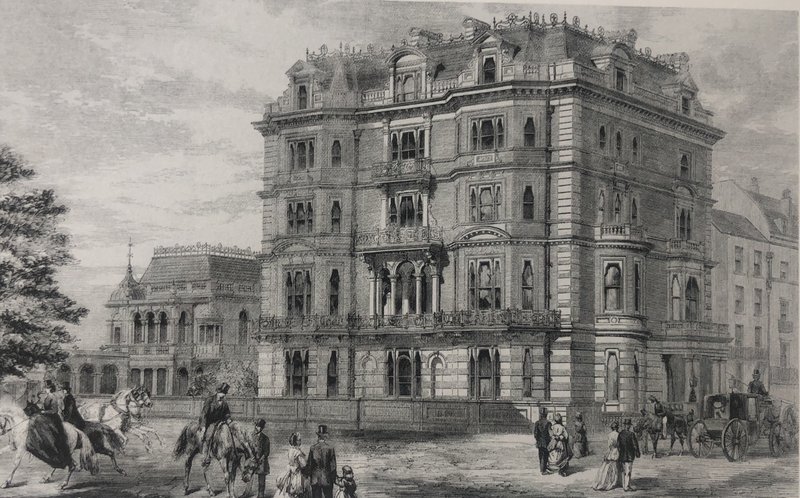

Thomas Henry Wyatt’s drawing of around 1866 marks the moment when the dream of Scottish businessman Dudley Coutts Marjoribanks (from 1880 Lord Tweedmouth) started to come true. After assembling several plots of land with smaller Georgian townhouses over ten years, Marjoribanks hired Wyatt, one of the most successful architects of the time, to build him a palace in what was becoming the very fashionable nouveau riche French style – particularly prevalent in the various financiers’ palaces around Hamilton Place and ‘Rothschild Row,’ the Western End of Piccadilly, the most notable extant versions of which are at 4-5 Hamilton Place.

The scale of Wyatt’s drawing suggests that it is a presentation drawing prepared for his client. In its monochrome precision, the drawing is deceptively sober – the building that was built was a riot of red brick and Portland stone – but shows off well the remarkable variety of flashy decorative elements: bow and bay windows, loggias, niches, round and triangular pediments, metal and stone balustrades, the odd turret even, and tall and elaborately crested roofs. It reads almost like a catalogue of possibilities presented to a patron who has replied ‘I will take the lot,’ a sort of architectural Mr Creosote.

The wafer thin mint of this visual feast is the tower, the tip of which can just be seen rising from behind the left hand side of the enormous roof. Given the already great height of the building for its period, the proposed tower must have been very substantial, and it is perhaps for that reason it appears to have been downplayed on this drawing, which no doubt would have been shown to the Grosvenor Estate for approval. In the end, however, complaints from less high rise (and less highfalutin) neighbours appear to have caused the construction of the tower to be abandoned, leaving this drawing as the only record of Marjoribanks’ Folly.

A separate pavilion (shown on the left hand side of the drawing) housed the billiards’ room and servants’ quarters and was linked to Park Lane and the house by an elegant colonnade.

Inside the grandeur continued with a mahogany staircase lined with a range of colourful marbles and the dining room fitted with the carved panels from a room in the recently demolished Drapers’ Hall. The first floor comprised an enfilade of gilded French style drawing rooms hung with Bouchers and Fragonards. Truly a dream come true, as one visitor noted:

There is no need for dwellers in Brook House to dream that they dwell in marble halls. They do dwell in them. They realise what the poet merely imagined.

The building received a mixed review from The Building News (2 October 1868) which described it as ‘remarkable, rather than […] handsome,’ regretted the use of polished granite and marbles and, interestingly, described the tower (indicating that the reviewer was in fact writing about the drawing in the Drawing Matter collection).

But More is More and when the house was acquired by Edward VII’s banker, Sir Ernest Cassel, in 1904 (from the 2nd Lord Tweedmouth who had fallen on hard times but not before having redone the first floor in Adam style for his wonderful collection of English furniture and Wedgwood now in the Lady Lever Museum in Port Sunlight) it was time for La Grande Bouffe. Cassel added buildings (having acquired a neighbouring plot) and quantities of marble, including 800 tonnes of white marble from the quarries of Seravezza in Italy (which Michelangelo had used for his work in the church of San Lorenzo, Florence) and blue marble from Ontario, Canada. The house was fitted with six kitchens and to the garden was added a dining room for 100 people hung with four magnificent Van Dycks.

When Cassel died in 1921, the house passed via his sister to his grandson-in-law and granddaughter Lord and Lady Louis Mountbatten. This once nouveau riche pile had become a Royal palace.

Lord Mountbatten (aka ‘Dickie’) was a keen sailor and his love of all things nautical extended to his bedroom:

Dickie’s bedroom had also been redone to resemble an officer’s cabin, complete with regulation bunk, brass rail, folding washstand, the simulated noise of the throb of a ship’s engine, and a porthole trompe-l’oeil, which, at the flick of a switch, presented a diorama of Valletta harbour by either day or moonlight. Against a painted background was a collection of cut-out ships at 50 feet to an inch that, when darkness fell, twinkled real Morse signals to each other. [1]

Wyatt’s building was demolished in 1931 to make way for a luxurious apartment building designed by Wimperis, Simpson and Guthrie (with advice from Lutyens). The building was in the monumental neo Georgian style so popular at the time and which can still be seen in The Grosvenor House Hotel (which had replaced Grosvenor House, another Park Lane palace, a couple of years before). The Mountbattens took a forty-room penthouse on the top two floors (each of the other substantial floors accommodated just one flat, including one for Mr Harry Selfridge) and boasted what was meant to be the fastest lift outside America. The Mountbattens’ apartment was decorated in a cool stripped classical style. Its most notable feature was the Rex Whistler murals and ceiling painting in Lady Mountbatten’s boudoir. And Dickie’s passion for films was indulged with a private cinema.

The final chapter in the story of Brook House begins in 1993 with the demolition and replacement in 1998 of the 1930s block by its new incumbent, a mixed use building of sixteen apartments and an Aston Martin showroom by Michael Squire & Partners, in many ways the TH Wyatt of our times.

In reviving the garish colour scheme of its grandfather (bright red and white) as well as its enthusiasm for multiple bay windows, the new incumbent brought a fresh dose of nouvelles richesses to Park Lane. Now, twenty-two years later, the new building is slowly patinating and dating, getting ready no doubt for its next makeover or perhaps a Royal occupant.

Follow the author’s ongoing perambulations around Mayfair: @mayfairbuildings.

Notes

- Andrew Lownie, The Mountbattens: Their Lives and Loves (London: Blink Publishing, 2019).