Casa Ugalde Sketch

– Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Dòriga

As José Antonio Coderch told it, Mr. Ugalde climbed on the hill, sat in the shadow of a carob tree and looked around him. He then hired Coderch and his partner Manuel Valls with the unique proposal of building a house in the outskirts of Barcelona that could preserve the feeling of that moment, and the views he had enjoyed.

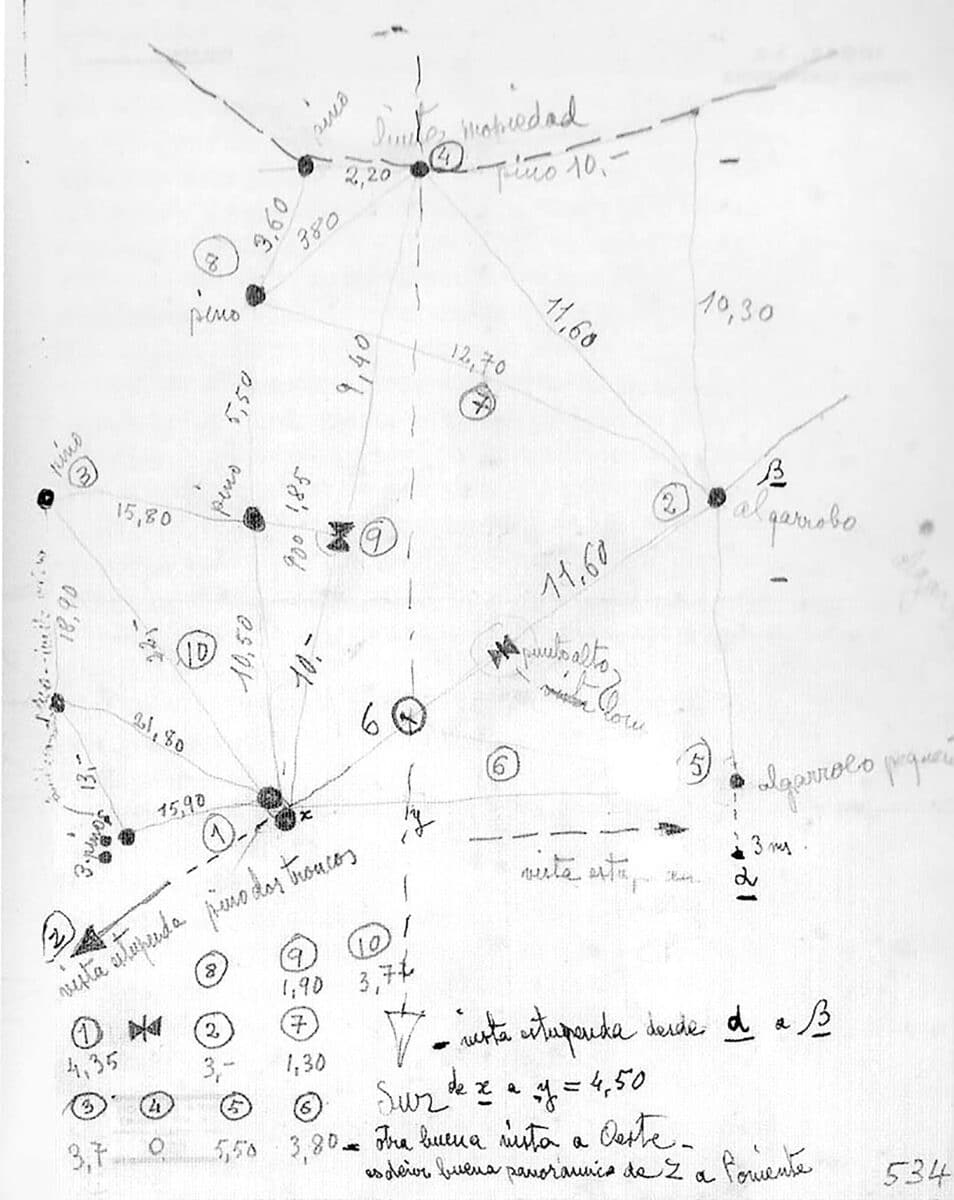

On visiting the site for the first time, Coderch observed the surroundings and took note of everything around him in the form of a sketch. It showed the precise location and species of every tree within the perimeter; including whether there was a group of more than one or if a pine tree had two trunks. It pointed out the direction of the best views.

There were no architectural intentions projected into the drawing, simply data written down on paper. With every distance, height, and angle measured, the resulting image resembled a treasure map. This drawing became an instruction manual of sorts, and the basis of the project.

As a result, the project was organised radially, instead of following an orthogonal system. The placing of walls followed the direction of the desired viewpoints, and was therefore freed from more conventional set square angles (30º,-45º,-60º,-90º). The straight fragments of the façade diverged from the curved lines of the garden retaining wall, and interior and exterior were intertwined in a continuous flow.

The most important formal decision of the project was to observe the landscape and to build from it. The house emerged from the ground, rather than being superimposed on it.

Casa Ugalde is a masterpiece, and yet Coderch was never fully satisfied with it. While he talked proudly of the process and early decisions of the project, he felt the ending result lacked order. It was not serious enough[1]. He sometimes said he would like to have the opportunity to start it all over again.

This might be the reason why the final plans of the house were not drawn until decades after it was completed. And it might also be why this sketch, probably done without much thought to its posterity, has in fact been preserved and repeatedly published.

The floor plans of the project are certainly not ‘pretty’ by any standards. They are not easily readable. And yet the feeling while moving around the house is one of pleasure and wellbeing, of a series of interwoven spaces, perfectly proportioned, where every small detail makes sense.

It’s a house where intuition leads over rationality, where an idea is successfully taken to its ultimate consequences, yet in a way that is difficult to rationalise through conventional graphic elements such as the plan. This might have been the source of Coderch’s consternation. With a military background, and as the son of an engineer, complete autonomy over his own project might have felt like a step too far. It was, however, prescient of ideas to come, and new methods of practice.

Finished in 1952, the house preceded the Situationists and their conception of psychogeography – which studied ‘the specific effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behaviour of individuals’[2] and also by over a decade, Sol Lewitt’s description of Conceptual Art – as art that materialises from a set of rules, rather than from the artist’s formal will.

In an architectural context, this perceptual approach to the site, which recalled the most common sense of vernacular architecture, would later be used by architects such as Álvaro Siza and Alberto Ponis. In the late 1950’s, Siza would visit the rocky coast of Matosinhos every day, studying it, drawing it, over and over again; searching for an architecture that made sense in that place. In the 1970’s, Alberto Ponis interrogated the landscape of Sardinia, looking for the best views, but also the best spot to attach his projects to the ground. On some of his houses, he would go as far as drawing them on site, at a 1:1 scale, with boards and wires, rather than using plans made in an office. The process behind these projects is similar to the one used in Casa Ugalde, and yet the resulting architecture is inevitably different. Each has a character of its own, connected to their author and the place from which they emerge. Many more examples could be found in this regard, but these three seem particularly connected for their relative proximity and similar climatology, and for their attention to the sea.

Even in the stormiest of days, the sea presents a radical, flat line in its horizon. Siza has said that, to him, the view of the Atlantic presents the prospect of an entire world. Maybe it is the certainty of this orderly presence and of what lies beyond, in contrast with the rough proximity of the land where we stand, which has been so attractive to humans throughout history.

This initial sketch for Casa Ugalde, in spite of its apparent triviality, would become a generative tool for the entirety of the project. It represents the balance between intuition and reason: an attempt to codify the impulsive desire to build a house that could formalise the feeling of an afternoon spent under the shadow of a tree, overlooking the sea.

Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Doriga share the architecture studio Bonell+Dòriga, founded in Barcelona in 2014.

Notes

1. “Now then, what influence have the years had on my work? Well, they have indeed had some influence: I should have worked harder to avoid some gratuitous disarray. Once you start, you often go too far. Just a little more order and seriousness.” Coderch on talking about Casa Ugalde in a conversation with Enric Soria, 1979.

2. Guy Debord, Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, 1955.