Casino Royale: Stynen’s unrealised sculpture garden

The city council of the seaside town Oostende organised a competition for its new casino-kursaal in 1945, and a design by Antwerp architect Léon Stynen was chosen as the winner the following year. Stynen was a prominent name by that time, having previously designed casinos for Knokke, Chaudfontaine, and Blankenberge.

He is considered one of Belgium’s most influential architects, with a career spanning from the early 1920s till the late 1970s, leaving behind a varied body of work. During this time, he was active as an architect, urbanist, designer and lecturer. After receiving his education in the beaux-arts traditions at the Antwerp Academy, he won a competition to design a war monument in the coastal town of Knokke, at the age of twenty-three. In keeping with his traditional background, the following years were dedicated to designing houses and apartments in the Art Deco style.

In 1925, while visiting the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris alongside his friend René Guiette, he discovered the work of Perret, Mallet-Stevens and Le Corbusier. This encouraged Stynen to immerse himself in the ideas and idioms of the avant-garde. A transitional period towards modernism can be seen in his Verstrepen Residence (1927) and the Knokke Casino (1928). For the latter, he revised his original monumental design with a more modern approach, favouring transparency, pure lines and spatiality – underscored by the presence of symmetry from his roots in the beaux-arts.

From the 1930s, Stynen was in high demand for private buildings as well as cultural institutions, such as the Ostend casino-kursaal. The modernist casino’s semi-circular glass wall offers views of the promenade and the North Sea, and creates a sense of openness and interaction between exterior and interior. The limestone is a perfect canvas for the sky’s reflection, its porous patterns decorating the building’s façade. Stynen tried to achieve a harmony between landscape and building, engaging the environment with the architecture.

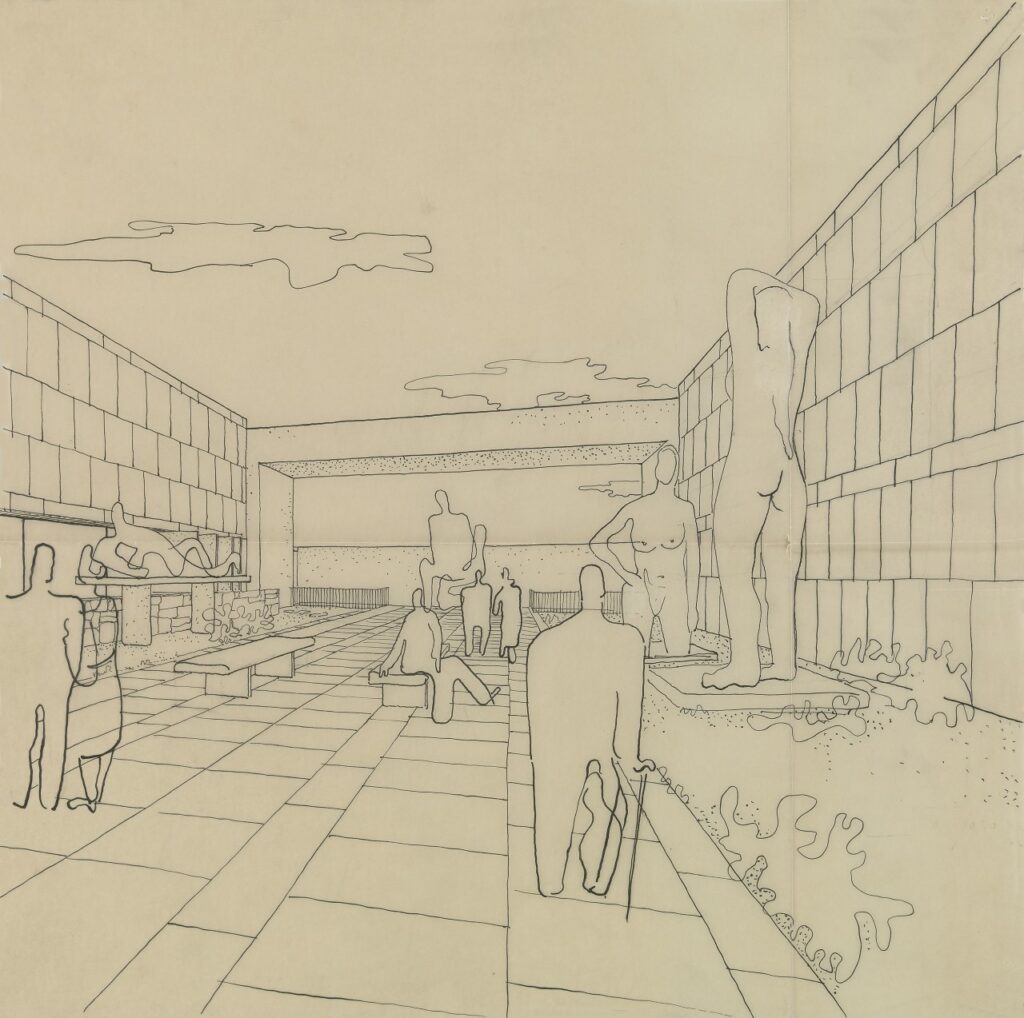

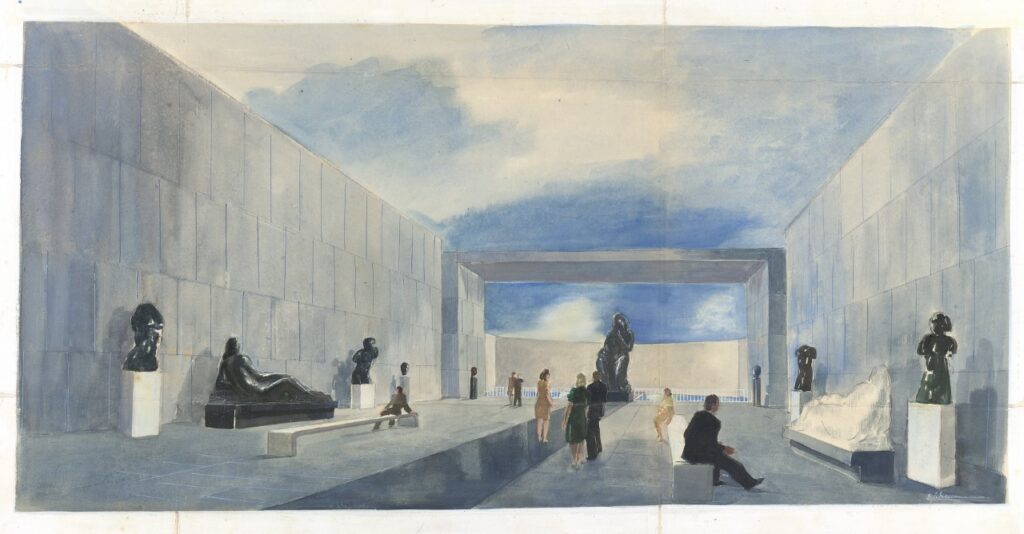

In his draft for the Ostend casino, Stynen – who was the son of a sculptor – proposed a rooftop sculpture garden. It was designed to enhance coincidental social interactions; one of his hallmarks was to create spaces in which circulation becomes an experience rather than an activity resulting from happenstance. Circulation spaces become staying spaces, their design germinates interactions that lend themselves to lingering. This effect is particularly clear in the first sketch, where the fluid outlines of the visitors mimic those of the sculptures. The layout of the unmaterialised garden steers the gaze towards a monumental sculpture piece at the end and draws the eye beyond, towards the horizon.

His sketches relay a sense of surrealism and dualism. The feeling of containment against the backdrop of an endless sky. An interesting dialectic results from the curious pairing of the chaotic antics a casino offers, and a space provided for contemplation. Stynen invites the visitor into a different realm, a different universe. His unrealised rooftop garden is a representation of that, leading the visitor to transition from the hubbub of the kursaal ,to the peaceful contemplation area of outdoor sculptures.