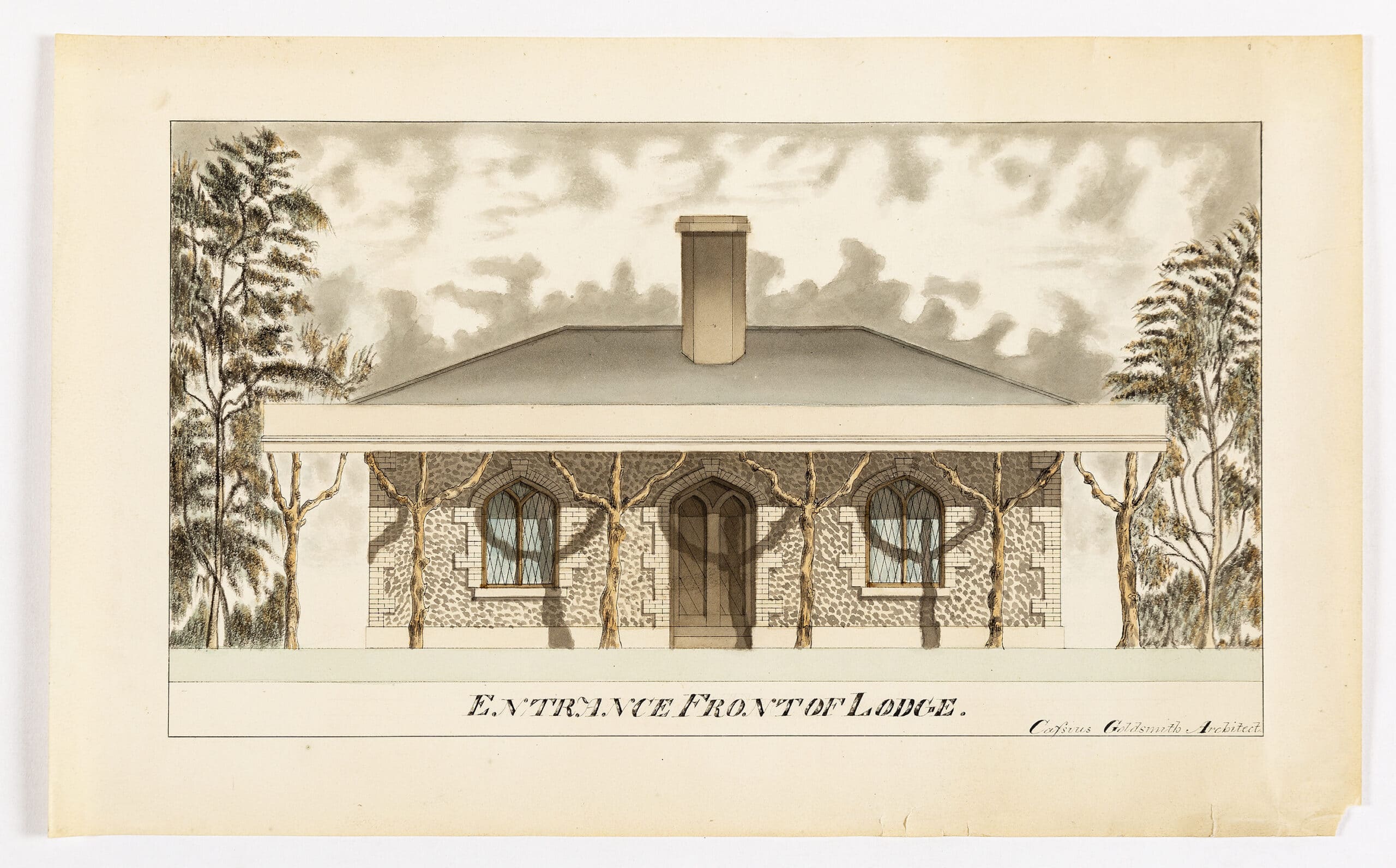

Cassius Goldsmith’s Grey Weather Gate House

I find myself lost in the woods, then reorientated, guided by the centralised chimney. Standing dead centre in front of the gate lodge, my gaze is lifted to the space between chimney and sky, between foreground or background. A cloud of white smoke disguises itself as an English cloud, passing west to east.

The brushstrokes guide my thoughts to many days like this one, a day too grey for making plans, consequentially revolving around a walk. The parks and forests of London provide me with an instant escape, only to find myself like this: face mirroring facade, waiting for some answers or clues. Then I think of all the curacao blue skies I have come across during my architecture studies, renders calibrated to ‘perfect day’ mode, with a glimmering building convincing us it’s utopia.

Cassius Goldsmith contrarily situates us as much in the present as in the past. Sunshine is not here to stay but to be frozen in Kodak. The Front Elevation of The Design for a Gate Lodge provides a more powerful guarantee. Between the trees, heavy hats held by sticks, there is a shelter for all those other mundane and overcast days of the year.

Past the context and slate roof, a silver plate reflects the sky, the shadows of the tree posts come to life. Prancing and holding hands, they conjure the spirit of Matisse. Far from the shamrock green and primary blue in Dance, the shadow figures around the lodge display movement while holding up the roof, joyous yet responsible.

I am immediately reminded of another youthful figure through a deep stare into the tree post to the right of the door. The Yaz, an endonym for the Berber people, is centred on their flag. He represents the motto ‘Free Man, Free Woman, Free People’. The Tifinagh character (ⵣ) is the pictorial representation of the first man on the planet, who stuck his feet on the ground, raised his arms, open to the universe, an equilibrium between earth and sky, an understanding of our humble size. But unlike caryatids, it is hard to believe the simple sticks around the lodge could support the roof.

Between the last tree posts on the veranda and the woods, I see hope. A shy blue sky hiding beneath the roofline and reflected in the windows.

The unbiased way of looking at artworks in a gallery is to first approach and take in the artwork, then contextualise and compare to the plate beside it. Seldom do I succeed. When I walk into an exhibition I usually engage in a habitual background check. But with this drawing, I succeeded, and only after losing myself in the Lord’s estate did I meet its habitants, the woodman, John Platt and his family. [1]

Perhaps it is the nature of the cottage or the picturesque scenery of a foggy forest, but imagining the Platt family has now evolved into a fairytale in my mind. Discovering the brief has made me an unintentional advocate of their life in their new home. I found myself torn between the possibility of larger comfort only provided to the Lordship, authorised further funds for separate sleeping arrangements for the girls and boys of the house, and the modest ‘humility’ of a cottage the Lordship rooted for. Humility, yes, rustic character, yes, but then John Wood’s words are evoked: ‘no architect can form a convenient plan unless he ideally places himself in the situation of the person for whom he designs’; how can the architect aspire to design rustic humility in another’s life?

Goldsmith’s preoccupations are like those of an involved psychologist, crossing that fine line between patients and their personal lives. When designing residential, how can we avoid crossing this imaginary line? Hours spent in the meticulous design of a closet for North London Project #4 at work invited my overstepping; in emails, unsent, asking about their laundry schedule and preferred hand to handle temperature when debating between wooden knobs or brass ironmongery. As a designer, I was taught to exercise input based on ergonomic understanding and aesthetic balance. My struggle is in the trend of the fake bespoke, items tailor-made for clients only known through correspondence or Pinterest boards. Perhaps it’s because the same nosiness is what brought me to architecture, marvelling at the interiors of friends’ houses and the set decoration on television, only to daydream about other people’s every day.

In the neighbourhood my mom grew up there is a row of very small pitched houses. Today, they are hidden behind a row of araucaria trees in a large golf course. These were my first understanding of a cottage, except they are made of corrugated metal and now have climbers over their exterior. Every time we revisited the neighbourhood growing up I would reencounter these houses, getting rustier and greener, and imagine the sweet life within. Recently I discovered that the row of houses, still standing, were the houses built by and for the builders who constructed the whole neighbourhood. Some lifted them onto large trucks and took them to other lands to build a home from. Some were left behind, abandoned then rediscovered. Today, someone lives there; the last time I passed by, I saw a rag hanging from the window.

Notes

- John Platt and his family are the fictional occupants of Goldsmith’s lodge in Philippa Lewis’s imagined account of the building’s commission.

Marie-Henriette has relocated to Oslo where she works as a pastry chef.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.

– Aris Kafantaris