DMJ – A Storyboard for the Fun Palace

Each community, with its own pride, wit and resourcefulness, could make a toy, a microcosm, a small city, a university-of-the-streets, a street theatre, a science playground, an adventure playground for the young kids – a place for time-wasting, gossip, new-arguing, learning, promenading, dancing, eating and drinking, handling tools, paint, machinery…

Hold on, who is going to do this, what with?

In every square mile there’s still the same balance of human values, the equation of joy and pain and all the other opposites. It only needs one bright spark to start the war on apathy. The composite mind is in, an agreed objective, understanding, the search, conflict – an explosion called discovery. If we tear off over-used labels ‘success’, ‘end-product’, and enjoy the problems for themselves, citizen thinkers-clowns-artists can do it themselves.

No fabric?

No more buildings. Light, air, space, water, pleasant shelters, expendable, variable and get the scale right…

ROLL UP – (This is the commercial)

The latest sci-fi-do-it-yourself time-wasting playground

A short-life toy to last, till the next age laughs at this old stuff… [1]

While there were many attempts to put the Fun Palace into words, this – perhaps more than any other – shows us how the project was rooted in a worldly critique of the impact of modern life upon artistic production. It is held in the British Library’s Joan Littlewood Archive, within a folder of documents dated October 1964, when Theatre Workshop’s Oh! What a Lovely War was playing in New York. It comes as no surprise, then, that the extended typed text brims with various references to the city – ‘the Mies building’, Central Park, Lincoln Center Theater, Jane Jacobs, the Marx Brothers and also to the life in the city of Brendan Behan – the recently deceased Irish author championed by Littlewood, whose play The Hostage had premiered at the Theatre Royal in 1958. The occasion of the text quoted is unclear, but its rhetorical character suggests that it might relate to an invitation Joan Littlewood received to present the Fun Palace on television upon her return to London some time in November that year. Its reference to ‘the commercial’ may point to the film project that she had developed to publicise the idea, anticipating its imminent broadcast.[2]

Cedric Price produced the Fun Palace storyboard to visually convey the project’s architectural components and their operation as the final sequence of this film (Fig.1).[3] Referred to as the ‘model sequence’ in some of the film scripts held in the Cedric Price archive at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, this closing sketch was intended to follow a sequence comprising documentary footage showing how Londoners spent their free time. It was filmed around the city’s East End – the milieu of Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop – in the summer of 1963, and subsequently titled Pleasure Film: Assembly.[4] The storyboard was probably an early study for the film and closely followed Littlewood’s Pleasure Film script. She envisaged the transition between London’s street-life and the Fun Palace as a transformation of the abstract mudflats in the London docks (seen from a helicopter) into the surface upon which the Fun Palace would be drawn: ‘69. Helicopter shot over London and river to last frame of mudflat/ 70. Dissolve mud to blackness/ 71. Draw in white on black quick moving outline of the complex.’[5] Thus, the ‘white on black’ of Price’s storyboard renders the progressive appearance of the project’s structural framework after the opening sequence ‘Mill Wall Mud flat (Glengall Wharf) Helicopter shot’ and ‘site blackout’. Abstract forms in the last vignette of the storyboard reference the ‘square shapes’ described in Littlewood’s script, intended to imply the range of activities on offer in the Fun Palace.

The storyboard is developed on a diazotype print, with marks then applied using ink, crayon, pen and graphite. This composite surface, measuring approximately 38 x 70 cm, conforms to the regular formatted sheets of the Fun Palace drawings. No title or date is indicated, only the scale ‘1/1250’. The drawing number ‘51.56’, the project title ‘Fun Palace Project’ and the details of Price’s office – ‘Cedric Price, M.A. Cantab ARIBA AA dipl. 88 George St. London, W.1 WEL 2387’– are stamped on it. Two graphic components organise the base drawing: first, a grid made up of four columns and three rows, which provides a series of twelve cells; and secondly, a small diagram of the project’s typical cross-section to scale, which is printed into nine of these.

Price’s hand annotates the print with graphic and textual commentary, respectively black and red. Quick lines animate and give vitality to the gridded surface. The light-hearted mood of the Fun Palace production condenses in effervescent pictograms that have been added. Echoing the stop-motion technique of filmic cartoons, a fixed frontal camera frames the cross-section shots – items 3–5, 8, 10 – in order to sequentially present the project’s capacious structural framework, followed by its spontaneous occupation with ‘objects’ – ‘boxes, platforms, eggs, crystals, etc.’– and operational environmental performance – ‘crane moving, roof, screens, sheets, boxes, exclusion of adverse weather’. Interrupting these repetitive frames, immersive scenes introduce some of the project’s varied environments and convey the dynamism experienced as one becomes surrounded by multi-level movement. And so, we read annotations such as ‘General impression of high-level movement – superimposed animated platforms and walkways’ (item 7), and ‘Close-up of element of 8. Mass movement – random and directional of people – recognition of human scale’ (item 9). Moreover, three such scenes are squeezed into the space typically allocated to notes and the key to reading the main drawing, while four of the cells with printed sections remain empty. With sketches loosely fitted into the master drawing, the layout of the story envisaged by Price has a shifting and provisional quality that resonates with the open-ended agenda of the whole project and its uncertain realisation.

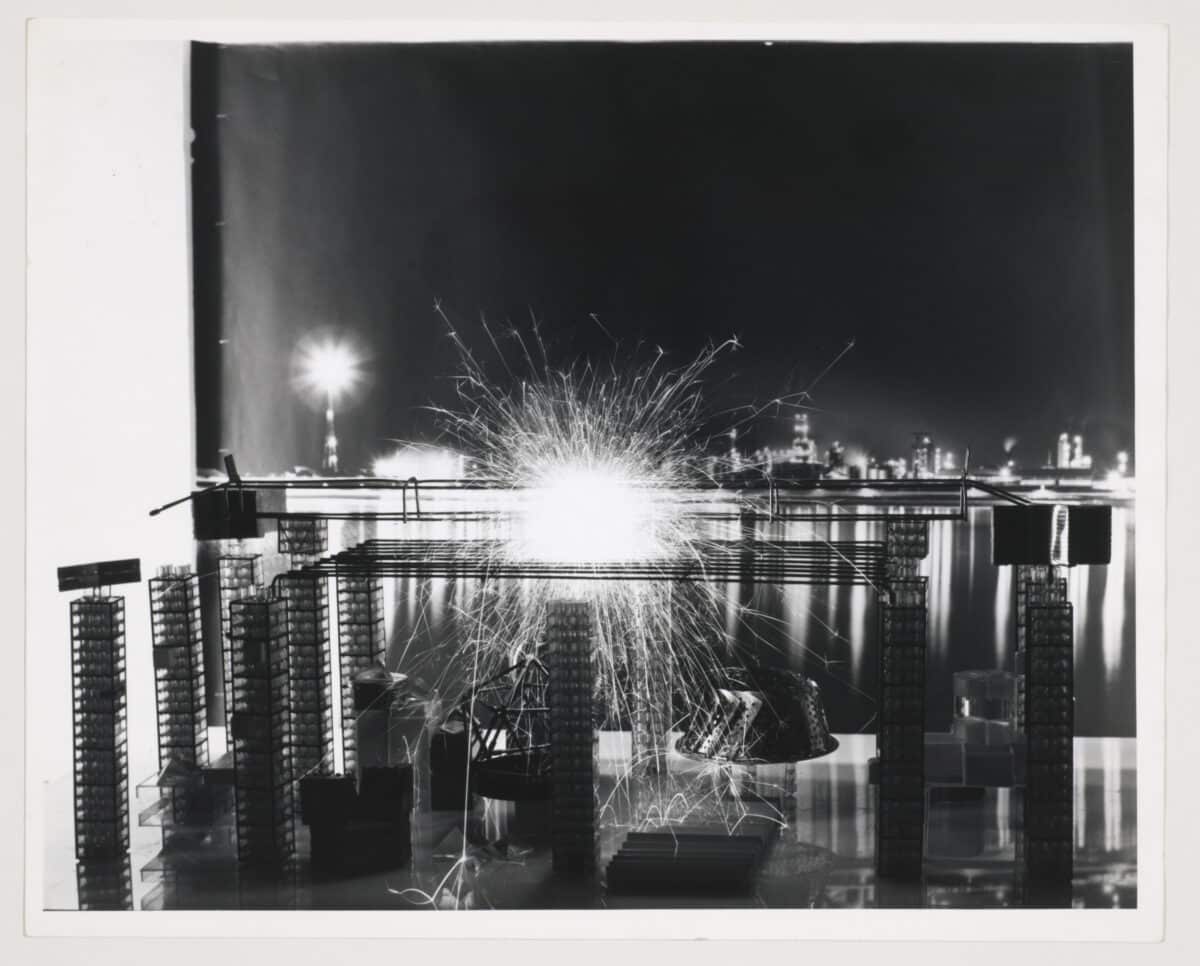

An unusual treatment for a frame in a storyboard, located in the middle cell of the right-hand column, draws our attention. A black cloudlike rubbing is annotated ‘Site black out – complete’, this – following the helicopter shot of London’s mudflats – anticipating the ecstatic encounter with the novel Fun Palace. Explosions burst recursively as the project is summoned into life in Price’s storyboard – item 4 reads: ‘framework blurs – explosions, isolated movements emphasised’, item 6: ‘move into particular box – say cinema, showing routes in and out – then “explode”’, and item 10: ‘The lot: movement – superimposed shapes, explosions, weather – in and ex site – changing to …’. Destruction was a condition of invention in Littlewood’s world-view. Early on, it was built into the idea for the film’s closing comic sketch. On 2 January 1963, she wrote to Price describing how a model of the project, a model that was also a toy, would simultaneously introduce the architectural features of the project and be destroyed by clowns: ‘Re: Pleasure Film / Suggest at end of film, after long shot of Glengall Site, pan in to model. Your voice explaining in your way. Your fingers seen poking at it / Cut to angle shot of Vic Spinetti, Barbara Ferris and maybe a child poking model and smashing or overturning part of it, maybe flooding or setting fire to it.’[6] A photograph of a toy-model lit with sparklers, hand-held fireworks, survives in Price’s archive (Fig.2). It was intended to be the last still of the film, according to a review of the footage by Price and the engineer Frank Newby (a.k.a. the self-titled,‘Moët et Chandon’) on 30 September 1964: ‘to indicate scale – final still of F.P. model with sparklers could be viewed closing in slowly – down a tower (say) to – in correct scale– the closing scale of clowns (superimposed) say “get your F.P. now”.’[7]

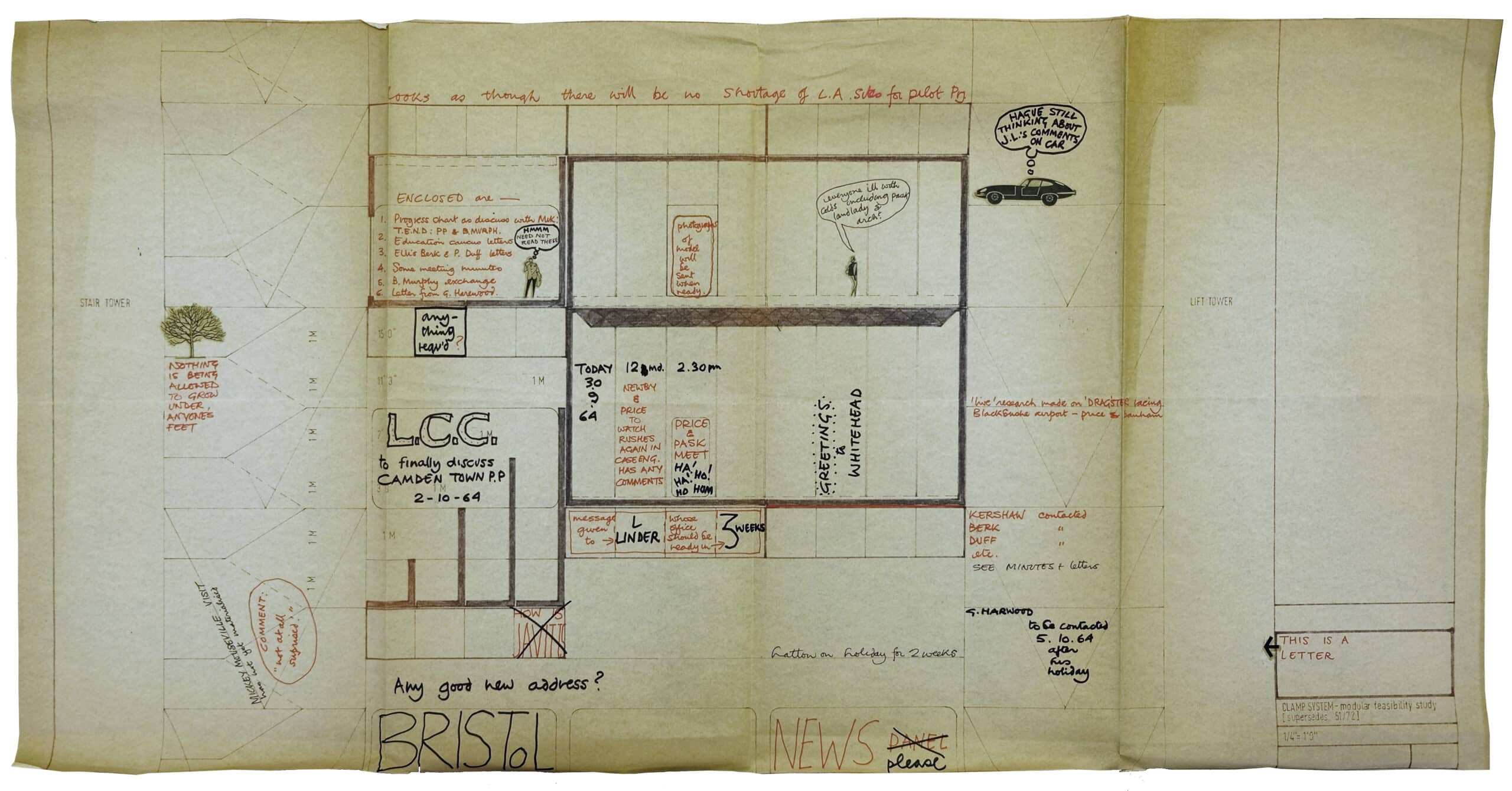

The meeting was recorded in a humorous collage that Price sent to Littlewood (who was possibly in the U.S. at the time) that day, with updates on several aspects of the production of the Fun Palace (Fig.3). Alongside notes such as ‘Hatton on holiday for 2 weeks’ and ‘photographs of model will be sent when ready’, a list of material enclosed with the communication included ‘a progress chart’ related to the production of the pilot project in Camden, and a range of letters exchanged with various collaborators. ‘This is a Letter’ exclaims the title box on the formatted drawing sheet, while a thought bubble emanating from a figure beside the list of enclosures reads: ‘HMMM need not read these’. To the left, a caption under a small tree collaged on to one of the landings of a ‘stair tower’ declares ‘nothing is being allowed to grow under anyone’s feet’. Like the storyboard, the ‘letter’ appropriates one of the Fun Palace project’s drawings, the ‘Clamp System – modular feasibility study’, no.51.78. Cheaply made copies of drawings with an articulated background, Fun Palace diazotypes became surfaces of exchange that supported a mood of critical yet playful commentary.

Was the Pleasure Film ever completed? Today, a constellation of documents of diverse provenance and scattered across various archives – scripts, minutes, letters, footage, photographs, drawings – allows us to trace something of how it was collectively imagined. With Price and Newby in the role of ‘clown-consultants’,[8] the film project acted as a productive contact zone where ideas, practices and expertise were fluidly and humorously exchanged. The storyboard for the end of the film suggests a joyful movement that transforms blitz into bliss (a ‘black-out’, of course, precedes the Fun Palace’s appearance) and embodies the essence of the project, as Littlewood repeatedly imagined it – delight as the spark that converts conflict into discovery.[9]

Notes

- Typed document, folder MS 89164/6/7, Joan Littlewood Archive, The British Library.

- Letter from Maurice Hatton, Mithras Films, to Joan Littlewood, 13 August 1964. Folder DR 1995:0188:525:002:003, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.

- The Fun Palace storyboard is part of the Howard Gilman Collection of Visionary Drawings, bequeathed to MoMA in New York in 2002. Selected by Price to convey the ‘general approach’ of the project, it was purchased in 1980 along with 14 other drawings following the commission of the Generator project for the Gilman Paper Company’s White Oak Plantation, Florida.

- Pleasure Film: Assembly, DR1995: 0188:525: 003:003, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.

- Ibid.

- Letter from Joan Littlewood to Cedric Price, 2 January 1963. DR1995:0188:525:002:001:010, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.

- Minute of meeting, Cedric Price and Frank Newby, 30 September 1964. DR1995:0188:525:002:003:018, Cedric Price fonds, CCA.

- Handwritten memo dated 11.12.66. Folder MS89164/6/49, Joan Littlewood Archive, The British Library.

- Having lived through the war, Littlewood conceived of the Fun Palace as a project to address violence in various guises – for instance, transforming East London bombsites into playgrounds through the Stratford Fair programme in the 1960s and 1970s. But she also tackled the effects of colonialism through comic plays and films she developed in Tunisia and India at the time, both included within the records of the Fun Palace in the Joan Littlewood Archive at The British Library.

Dr Ana Bonet Miró is a Senior Lecturer in Architectural Design at the University of Edinburgh, and an architect. She is co-curator of the touring exhibition ‘Delightful Fun’: a Cedric Price Thinkbelt for our times (2024-25) and author of Architecture, Media, Archives: The Fun Palace of Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price as a Cultural Project (2024).

*

The article is included in the third issue of DMJournal, Storytelling.