Drawing from a Deep Well

LEWERENTZ'S ST PETER'S, KLIPPAN

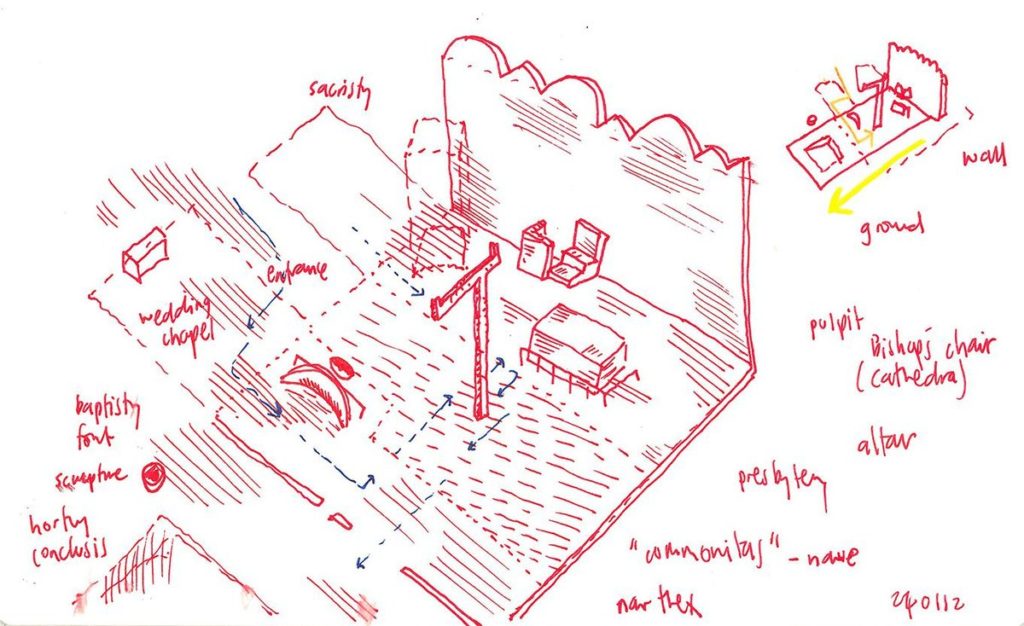

I make several different types of drawings in my life as an architect and as a teacher: those made at the speed of thought in B4 sketchbooks, on my lap or at the dining table or on trains or buses; tracing drawings made on bits torn from rolls of detail paper, usually made in meetings with colleagues; or drawings made to try to explain ideas to other people, usually on single sheets of paper, A4, A3 or A1, laid out on the office meeting table. I enjoy the first for the feeling of being fully alive, completely absorbed in something that requires intense concentration, yet aware of the lightness and freedom of what appear to be spontaneous moments of thought. The other sorts of drawings require slower movements: looking, changing one’s mind, adjusting.

The majority of the drawings here were made over a period of about a week, in late January 2012, for a PhD supervision with Professor Peter Carl. My investigations into the relationships between architecture, sculpture and site had hit a wall, but something Peter said in a seminar unblocked my subconscious and imagination, and these drawings flowed out of me like water breaching a dam. The dam in question was perhaps the predominant way of looking at and thinking about St Peter’s Klippan. Sigurd Lewerentz’s great masterpiece is often – if not almost exclusively – described simply as a church reduced to a brick wall. This dominating view of architecture reduces it too to a ‘religion of bricks’, as Iñaki Ábalos once memorably remarked.

A week or so before my Damascene moment, Peter had nonchalantly observed that unlike most modern churches, the majority of Victorian churches – of whatever style or denomination, regardless of the architect’s talent, and despite various twentieth-century re-orderings – continue to work well. We then began to make a (very short) list of modern churches that ‘work’ for parochial use. St Peter’s Klippan, despite its striking appearance and seemingly empty interior – despite also various architects’ eulogies to emotional brick work and subjective form; and unlike Le Corbusier’s St Marie du Haut pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamp, or Rothko’s little college chapel at St Thomas’ University in Houston – St Peter’s is quite an ordinary parish church, and it works very well for the people of Klippan. How? Why?

I began to draw what I remembered of the church and what I knew about the ideas of its inception, using the tools that I had to hand on my desk in my architectural practice. We were preparing the tender information for a very large commercial and residential project in London at the time, and I drew in between meetings and telephone calls.

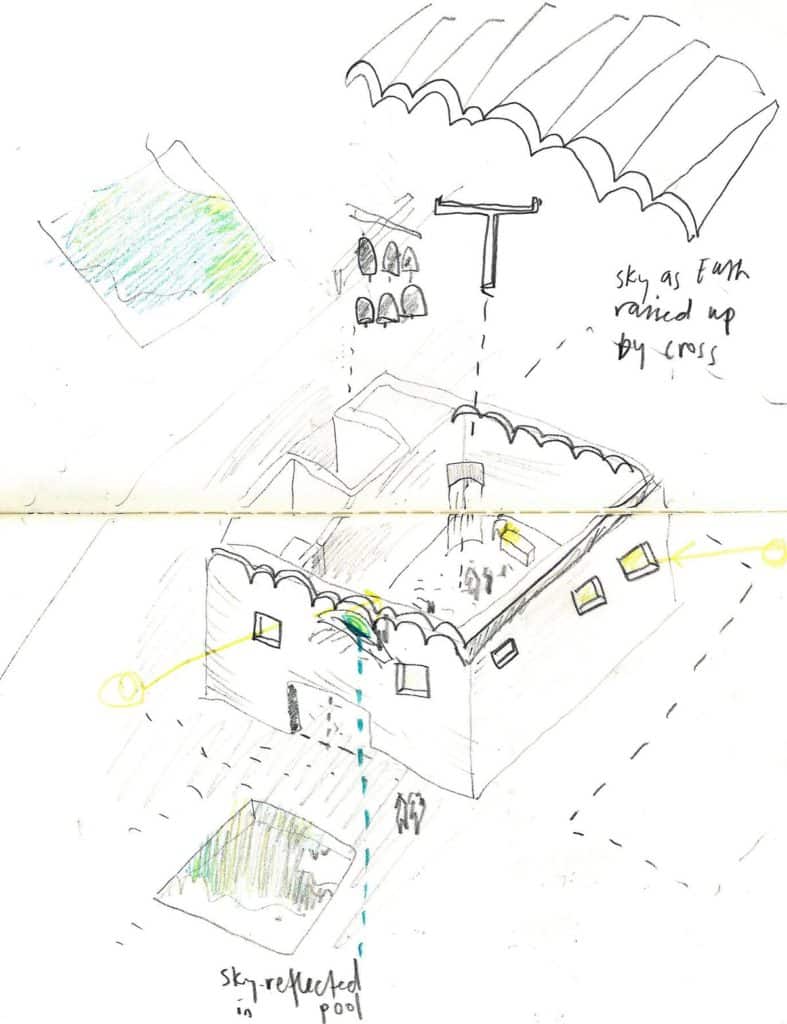

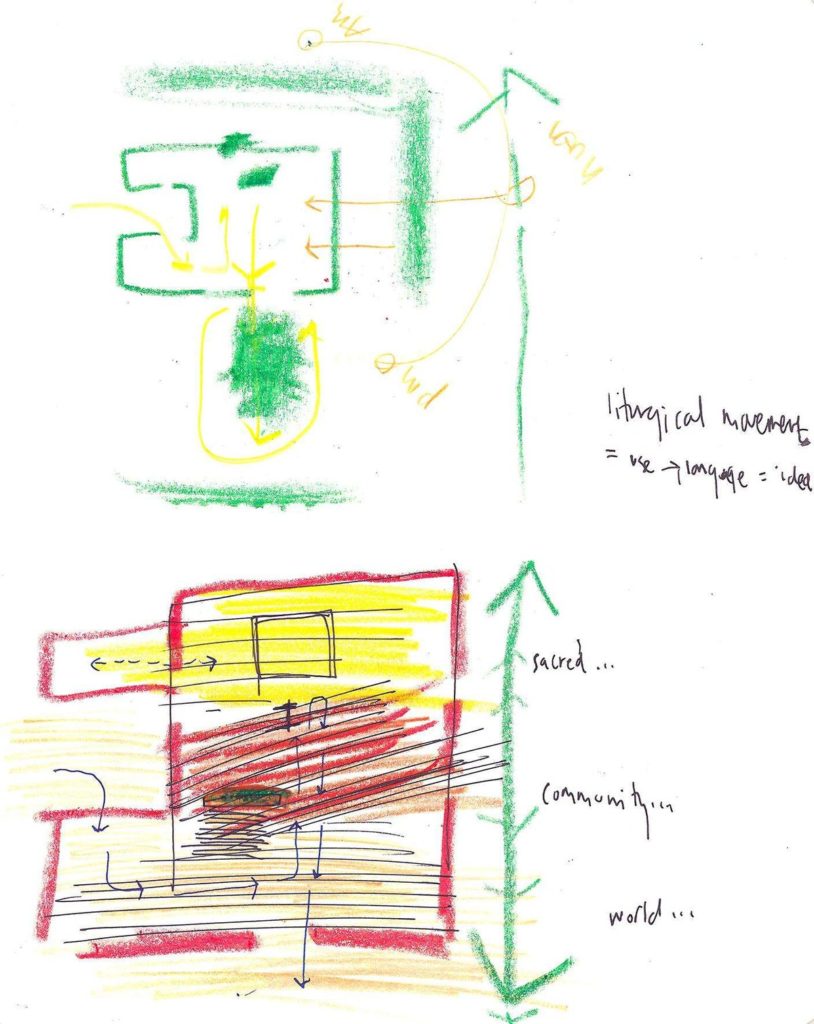

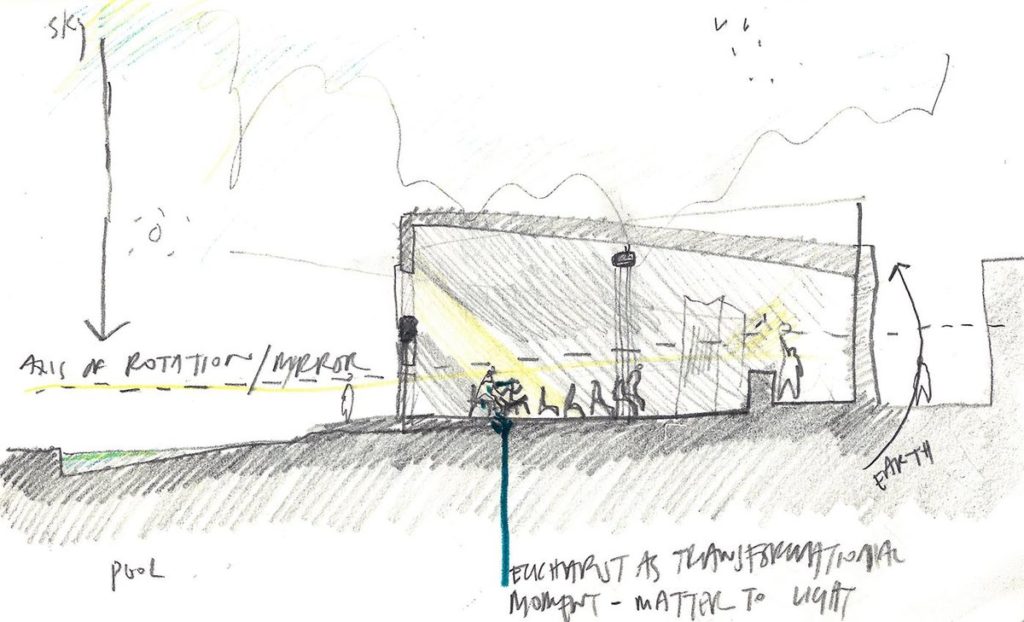

Lewerentz was very lucky to have had an extremely intelligent and sensitive and witty client for St Peter’s, a priest called Lars Ritterstedt. Ritterstedt was in fact not the local priest (who would have been happy with a shed) but the expert client for architectural and artistic matters for the Diocese of Lund, representing the Archbishop. When he retired, Ritterstedt wrote a PhD at The University of Uppsala, entitled Adversus Populum, about his role in the creation of a number of churches with Peter Celsing and Sigurd Lewerentz. With his guidance, and the help of a translation by Nina Lundvall, I began to understand the symbolism of the church. It is, like all Christian temples, a series of spatial settings for the commemorative reenactment of events in the life of Jesus: his baptism by St John the Baptist in the River Jordan and the events of Holy Week that are remembered in the liturgy of the Eucharist (The Last Supper, Good Friday, Easter Sunday, etc). There are no paintings at St Peter’s, so these events are recalled instead as spatial images: they only become visible over time, through direct experience and on reflection, developing in the mind through contemplation. The only way I could try to understand these and to explain them to myself was by drawing them.

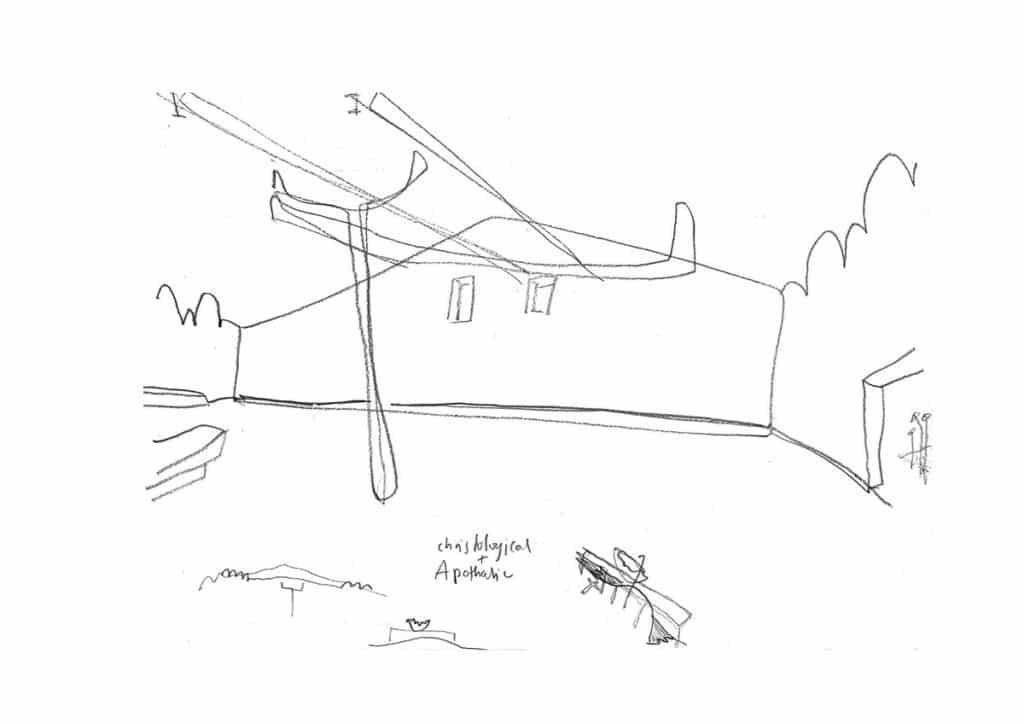

I realised that the fetishisation of the beautiful, mainly black and white photographs of the empty building – no matter how beguiling they were in aesthetic terms – was a misdirection, depriving us of insight into the great imaginative achievements – the wit and intelligence – of the design team. However, the photographs do reveal that rather than being empty, the architecture of the church is complimented by ornamental equipment and artworks. The former is mostly designed by the architect – the processing cross, the brick bishop’s chair, the bracketry that supports the conch shell at the font, the street lights, the metal numbers that tell you which hymns to sing – whilst the latter are the work of artist and poet collaborators – the poem cast in bronze dedicating the bells, the hanging tapestry, the stone sculpture beside the pond, etc. My problem was to try to understand what all of this immense creative effort and energy meant. I’d been led to believe that the church was aniconic, and taught that Luther had proscribed imagery: how to explain then all of this previously overlooked stuff? My drawings are partly the notes of an architectural detective, and partly attempts to understand how certain philosophical concepts might work in relation to the themes at play in the iconography at St Peter’s – for example, the links between the visible and the invisible in Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception, since it was clear from my research that modern sculptors including Donald Judd, Robert Irwin, Richard Serra and Robert Smithson, revered this book.

It occurred to me that the minor cult of the Lewerentz’s construction drawings (as interesting as they are) is also misleading, creating the impression that Lewerentz was a materialist. Working drawings and details don’t really describe what is happening in a church, of course – they can’t, they’re not drawn to communicate meaning or use. I became increasingly convinced that to examine a plan as simply a combination of lines (the Wittkower-Rowe-Eisenman trajectory) was similar to studying musical notation without listening to the actual music. So my alternative method of studying buildings via a new way of drawing them (as the spatial settings for rituals ornamented with anthropological use and artworks) needed a complimentary mode of phenomenological involvement: participation.

I decided, heeding Wittgenstein’s advice, to ‘look for the meaning in use’, and so the rest of the drawings – the rougher pencil drawings and the ones which are mostly words – were made a month or so later in a hotel room in Lund after I’d attended Mässa at St Peter’s on a snowy Sunday in February. I could try to tell you now what the building means, but I think the drawings do this much better.

In terms of technique, most of these drawings are similar to the sort of marks I make when I’m designing; marks made not for effect, but as records of thoughts of which I am both originator and original audience. I realise in retrospect that they are also similar to the types of drawings that I make in design tutorials, trying to understand and to explain to myself and the student sat beside me what it is we are seeing together in their work. In this sense I think these drawings are almost exactly like design drawings, because in each instance one is interpreting and creating at the same time: remarking on what you’ve thought previously; redrawing ideas again and again until they come into conceptual focus, and they become clear, as images. This process isn’t entirely mental however, it’s impossible without the bodily rhythms of drawing, just as thinking is famously helped by walking.

My drawings of St Peter’s still surprise me. They’re evidence of a hand and mind taking an imaginative walk together, and affirm my faith in Carlo Scarpa’s assertion: ‘I draw so that I can see.’

It’s no accident that in English we use the same word to say we ‘draw’ a picture, ‘draw’ water from a well, or ‘draw’ curtains open or closed. Drawing is a source of refreshment and enlightenment, and a deep wellspring of hope, I think.

Patrick’s book, Civic Ground: Rhythmic Spatiality and the Communicative Movement between Architecture, Sculpture and Site, is available from Artifice Books on Architecture.