Ernö Goldfinger: Westminster Bank

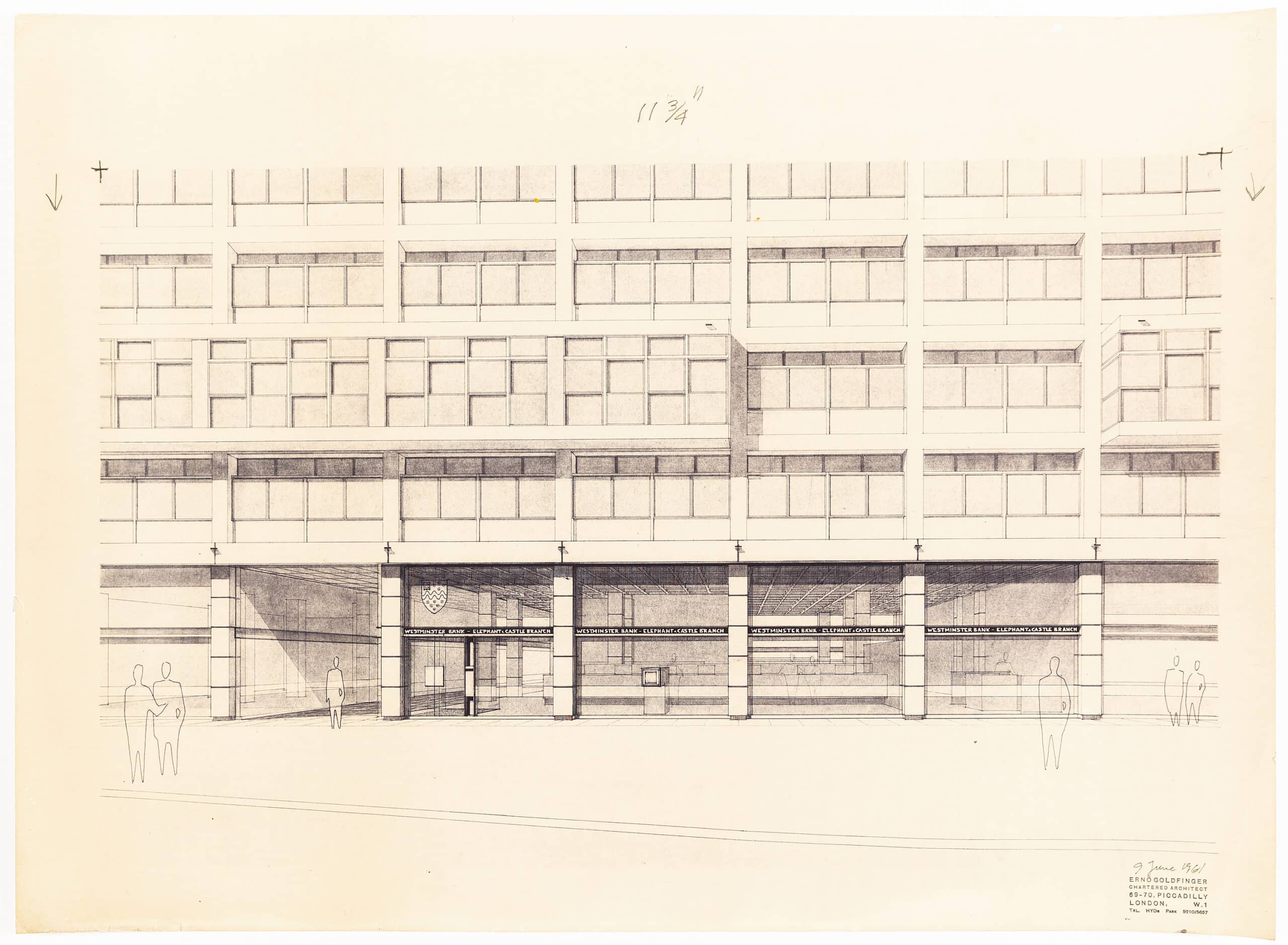

Looking at Ernö Goldfinger’s drawing for Westminster Bank at Alexander Fleming House in London, the first thing that stands out is its grid-like form. The frame of the building and its windows form a grid, and a grid within a grid, respectively. A peek inside the carefully drawn ground-floor windows shows a gridded ceiling. The drawing fundamentally reveals itself to be the work of a highly rational mind.

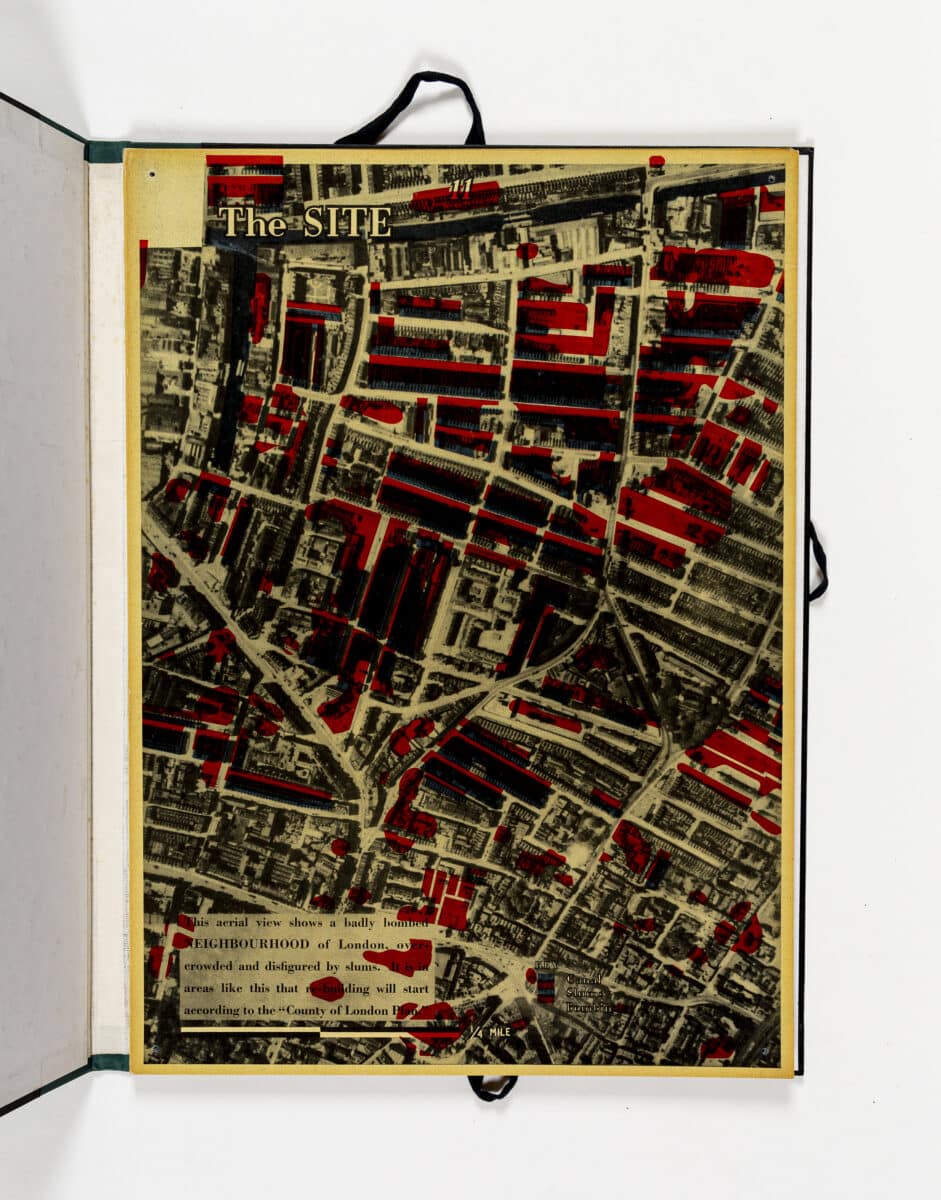

Alexander Fleming House, now Metro Central Heights, was constructed in the early 1960s by Goldfinger and his office for Arnold Lee of Imry Properties Ltd. Named after Alexander Fleming, the Scottish physician who first discovered penicillin in the 1920s, the building’s original name reflects its first primary tenant: the Ministry of Health. It is located on Newington Causeway, which forms the northeast side of the Elephant and Castle junction. This south-London site had been badly damaged during the Second World War, and, as such, became one of the London County Council’s foremost comprehensive redevelopment areas.

The London County Council’s brief for the redevelopment of this part of south London called for a combination of business, retail and entertainment constructed ‘on a scale worthy of its important situation’, thus recognising Elephant and Castle as a key node linking central London to the south.[1] The LCC wanted Elephant and Castle redeveloped so that it would become an example of ideal civic design, asking for buildings of similar height accompanied by ‘an imposing tall building’ in the north to act as a focal point, and for the space created by the two roundabouts to be integrated into the design.[2] A series of competitions sought to find teams of developers and architects to build this ambitious project on a series of five sites, making it clear that the winner would be the best and not necessarily the most profitable design. In July 1959, Goldfinger and Imry Properties’ scheme was selected from a pool of nine applicants to construct a commercial and office development adjoining the existing Trocadero cinema (later demolished and rebuilt by Goldfinger as an extension to the site).[3]

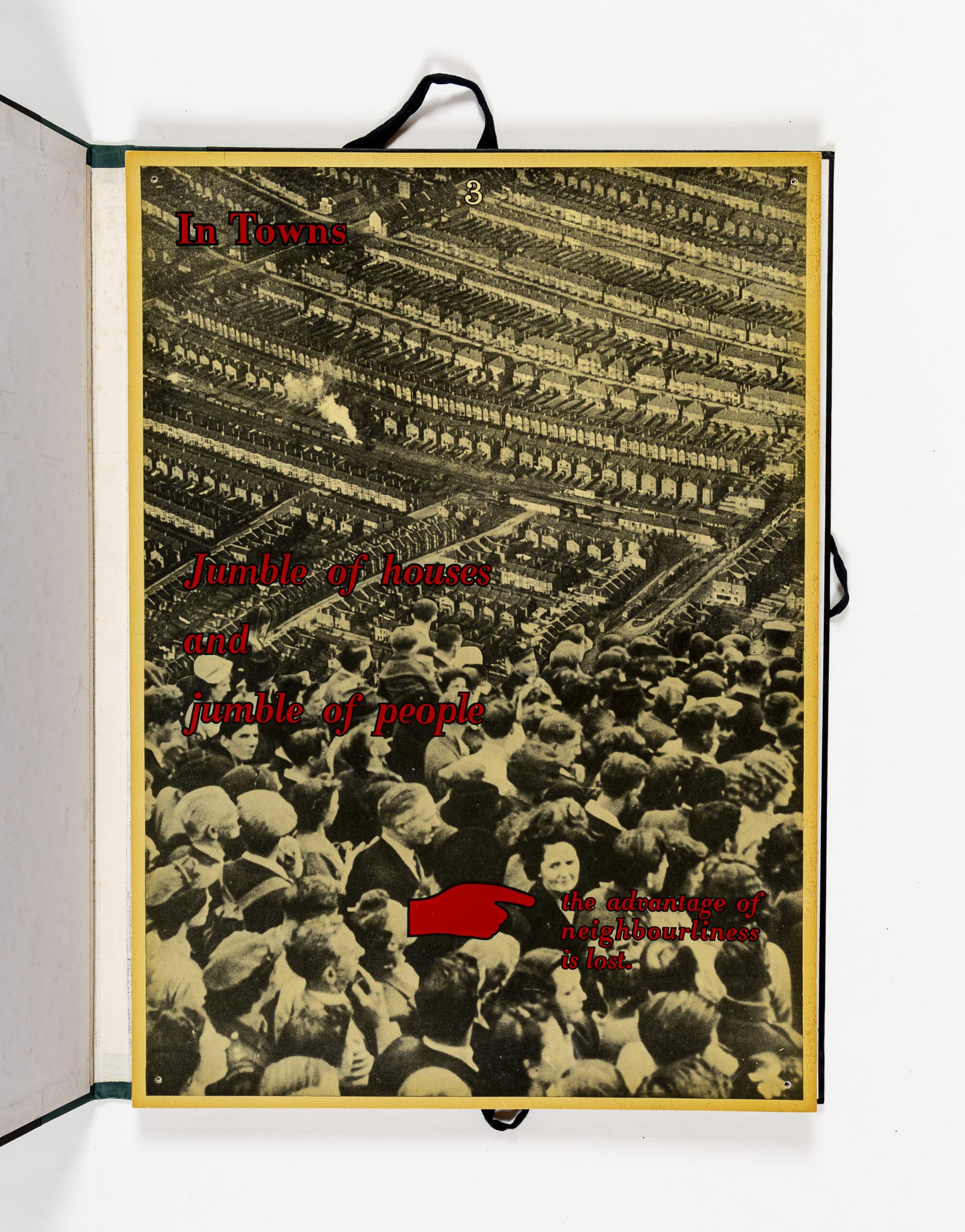

Goldfinger had developed expertise in large-scale urban projects through the exhibitions that he and his wife, Ursula Blackwell, had produced for the Army Bureau of Current Affairs, including The County of London Plan (1944), Traffic (1944) and Planning Your Neighbourhood (1945), all of which explored the topic of rebuilding London after the Second World War for non-professional audiences. He also had worked with Edward Julian Carter on a highly illustrated book that looked at John Henry Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie’s 1943 County of London Plan (1945). While these projects had been aimed at non-professional audiences, Goldfinger published his own views on urban planning for fellow architects in a series of articles published by The Architectural Review between November 1941 and January 1942. These articles examined the development of modern cities and explored the function of urban spaces. Together, these projects illustrate that Goldfinger always understood architecture as part of a wider context of urban planning, which he brought to fruition in his design for Alexander Fleming House.

Key to Goldfinger’s design, and explored in his articles for The Architectural Review, was the effect of architecture, which in this project meant avoiding ‘the monotony of a continuous unbroken façade’.[4] Part of his solution to this problem was to create three separate blocks—two of eight, and one of eighteen storeys. These were later joined by two additional blocks and a cinema, located on the site of the former Trocadero. The blocks were sited around open garden spaces that office workers could use for recreation, with the tallest block forming a focal point. Block ‘A’, shown in this drawing, was to front onto Newington Causeway with a street-facing façade of approximately 216 feet long, and comprising a basement, ground floor and upper floors. The ground floor was designed as commercial space for use as shops, a pub, and branches of Westminster Bank, shown here, and Midland Bank.

As evidenced by their situation on Newington Causeway, the three original blocks forming Alexander Fleming House were almost certainly meant to be viewed at speed, as from an automobile or bus. Like other modernist architects, perhaps most notably Le Corbusier, Goldfinger himself had a fascination with automobiles and driving. An important aspect of the design of his own home, for example, had been the two garages which are a prominent part of the façade’s design. In his article ‘Urbanism and the Spatial Order’, Goldfinger explained the significance of the point of view of the user, including the fact that increasing speed of transportation had impacted the ‘spatial order’ of cities.[5] It follows, then, that the way Goldfinger conceived of the project, with the tallest block of the three acting as an urban focal point, was at least in part motivated by this understanding of urban space.

Goldfinger’s other solution to relieving monotony was through his treatment of the façade itself. In his design some of the building’s window bays projected while others were recessed. This is clearly expressed in the drawing, which shows the bays two floors above the entrance to Westminster Bank projecting to form bay windows and the floors above and below it receding to form colonnades. Goldfinger had previously used this type of façade in his design for 45-46 Albemarle Street, London, built in 1955. Here Goldfinger created two six-storey office buildings using a unified design that included projecting bays on the second and fourth floors. A similar solution also appeared in Goldfinger’s proposal for an office building at 69-70 Piccadilly, London, with projections and recessions of the bays appearing on the third floor. Together, the designs for Alexander Fleming House, 45-46 Albemarle Street and 69-70 Piccadilly presented ways of expressing a concrete frame with a clear sense of rhythm and variation.

The visible expression of the structure of each block on the façades of Alexander Fleming House spoke to Goldfinger’s conviction that ‘it must always be possible to see, and feel, how a building is supported’.[6] He rejected glass curtain walls which were by the 1960s popular in modernist office architecture, such as Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York (1958). Goldfinger’s belief that a façade should reveal a building’s structural members came from his mentor, French architect Auguste Perret (1874–1954), himself a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete. Perret viewed concrete as a new kind of stone and believed that it should be treated according to principles of French structural rationalism wherein a building’s structure could always be read on its façade. Accordingly, Goldfinger’s façades for Alexander Fleming House clearly expressed the building’s support system, with structural members treated in bush-hammered concrete on the upper floors and polished granite on the ground floor.[7] This frank expression of the structural frame appeared in buildings throughout Goldfinger’s career, including his best-known works, Balfron Tower (1967) and Trellick Tower (1972).

The notion of impermanence was central to the design of modernist office buildings, which were often designed as open floors that could be partitioned into smaller, purposed spaces as needs changed. Goldfinger’s approach to the design of Alexander Fleming House supported this goal. He generally favoured planning buildings on a grid of 2’9” (84 cm) and its multiples, a measurement that was based on the proportions of the average male human body. This idea had first appeared as a planning principle in Goldfinger’s exhibition Planning Your Homes (1946) on a panel titled ‘to the measure of man’. It was this planning principle that Goldfinger used for Alexander Fleming House, whose columns he spaced at intervals of 16’6” (5.04 m).[8] He suggested that two window widths formed the smallest room, while an entire floor could be one large room. Goldfinger designed each of the three blocks to be used flexibly, meaning that each block could be used either independently or linked together by bridges. This spoke to Goldfinger’s understanding that the use of a building was often temporary and indicated that he was building longevity into the project.[9] That Goldfinger factored flexibility and longevity into the design proved prudent. Now called Metro Central Heights, each of the blocks has been transformed into residential space, with the office floors divided into flats ranging in size from studio to three bedrooms.

Notes

- London County Council, ‘A General Description of the Proposals for the Redevelopment of Elephant and Castle’ (undated), 7. Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr\5\1A, RIBA Archives.

- London County Council, ‘A General Description of the Proposals for the Redevelopment of Elephant and Castle’ (undated), 13. Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr\5\1A, RIBA Archives.

- Elain Harwood and Alan Powers, Ernö Goldfinger (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2024), 87.

- Memorandum for the Proposed Development of Site Two, 2. Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr\5\1B, RIBA Archives.

- Ernö Goldfinger, ‘Urbanism and the Spatial Order’, The Architectural Review (December 1941), 166.

- Quoted in Robert Elwall, Ernö Goldfinger, RIBA Drawings Monographs No. 3 (London: Academy Editions, 1996), 17.

- ‘Offices: Elephant and Castle, London, Ernö Goldfinger’, The Architectural Review (January 1960), 43.

- Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr\60\9, RIBA Archives.

- Memorandum for the proposed development of Site Two, 3 and 6. Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr\5\1B, RIBA Archives.

This drawing by Ernö Goldfinger from the Drawing Matter Collection is currently exhibited in Soane and Modernism: Make it New at Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Dr Erin McKellar is Assistant Curator (Exhibitions) at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. Here she leads the online exhibitions programme and curates shows in the gallery on modern and contemporary architecture. Her exhibitions reveal how Soane’s ideas are reflected in 20th- and 21st-century design. Her independent research centres on the design cultures of the 1930s and 1940s. She is the curator of Soane and Modernism: Make it New.