Alberto Ponis, The London Years

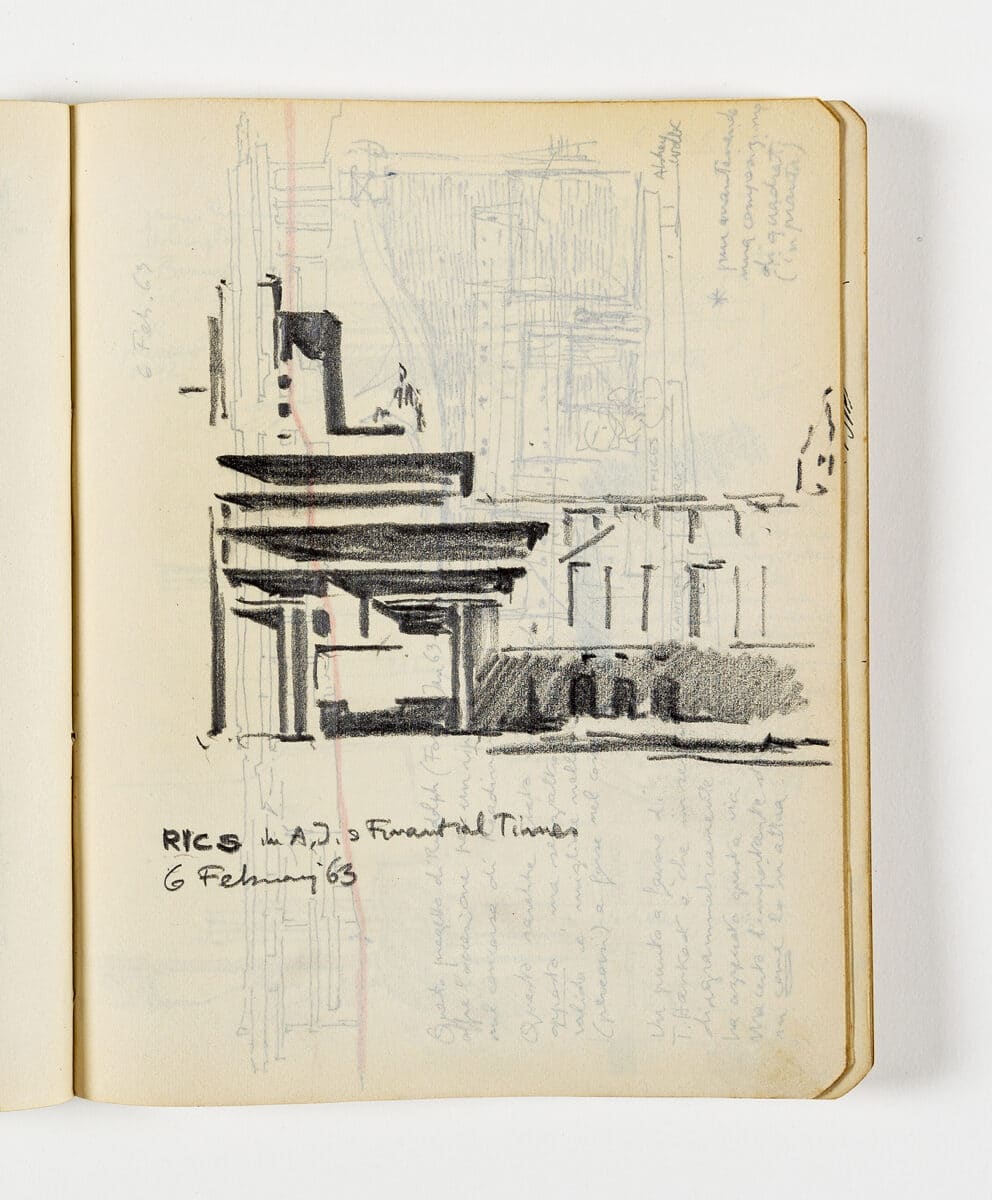

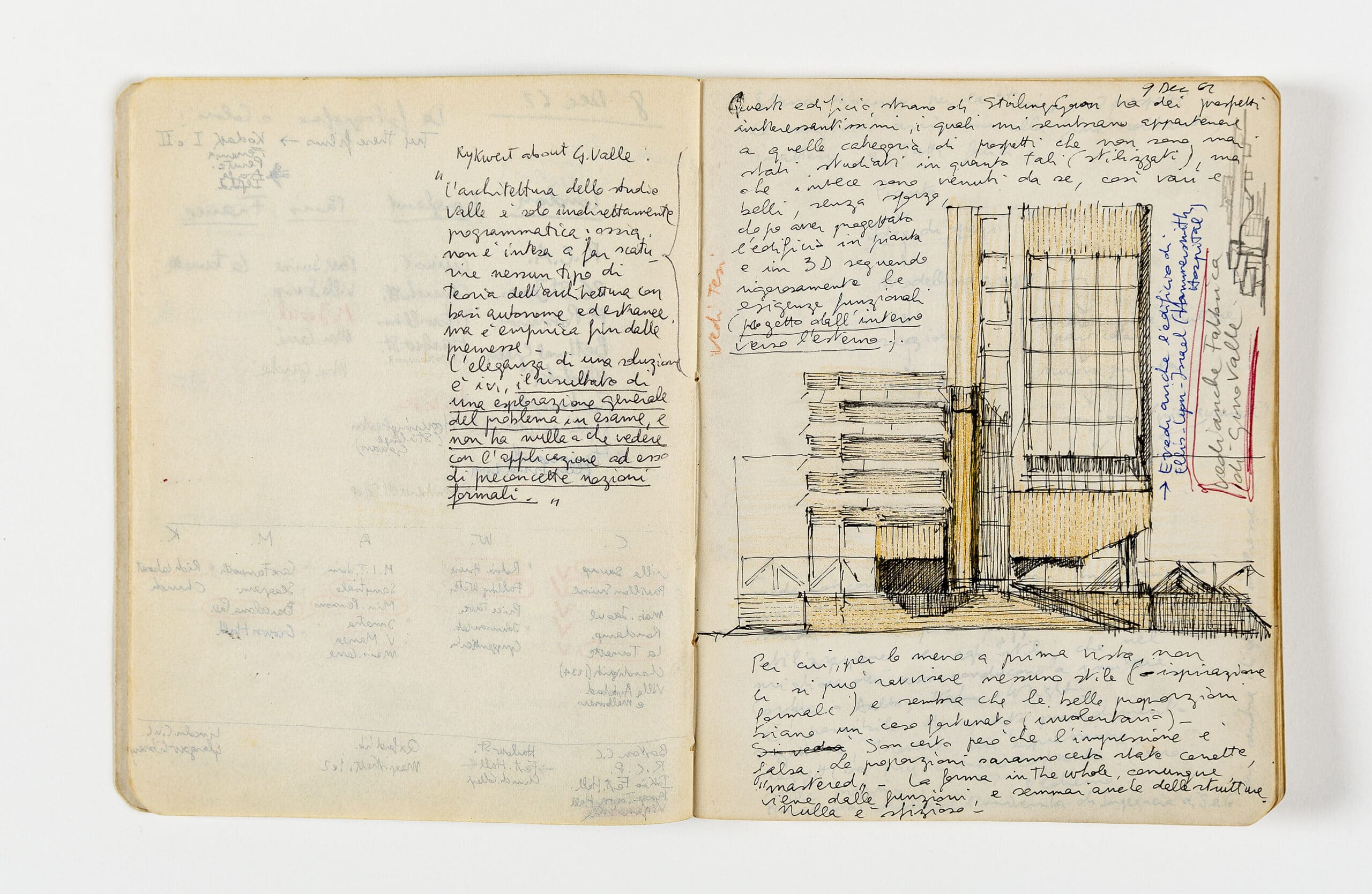

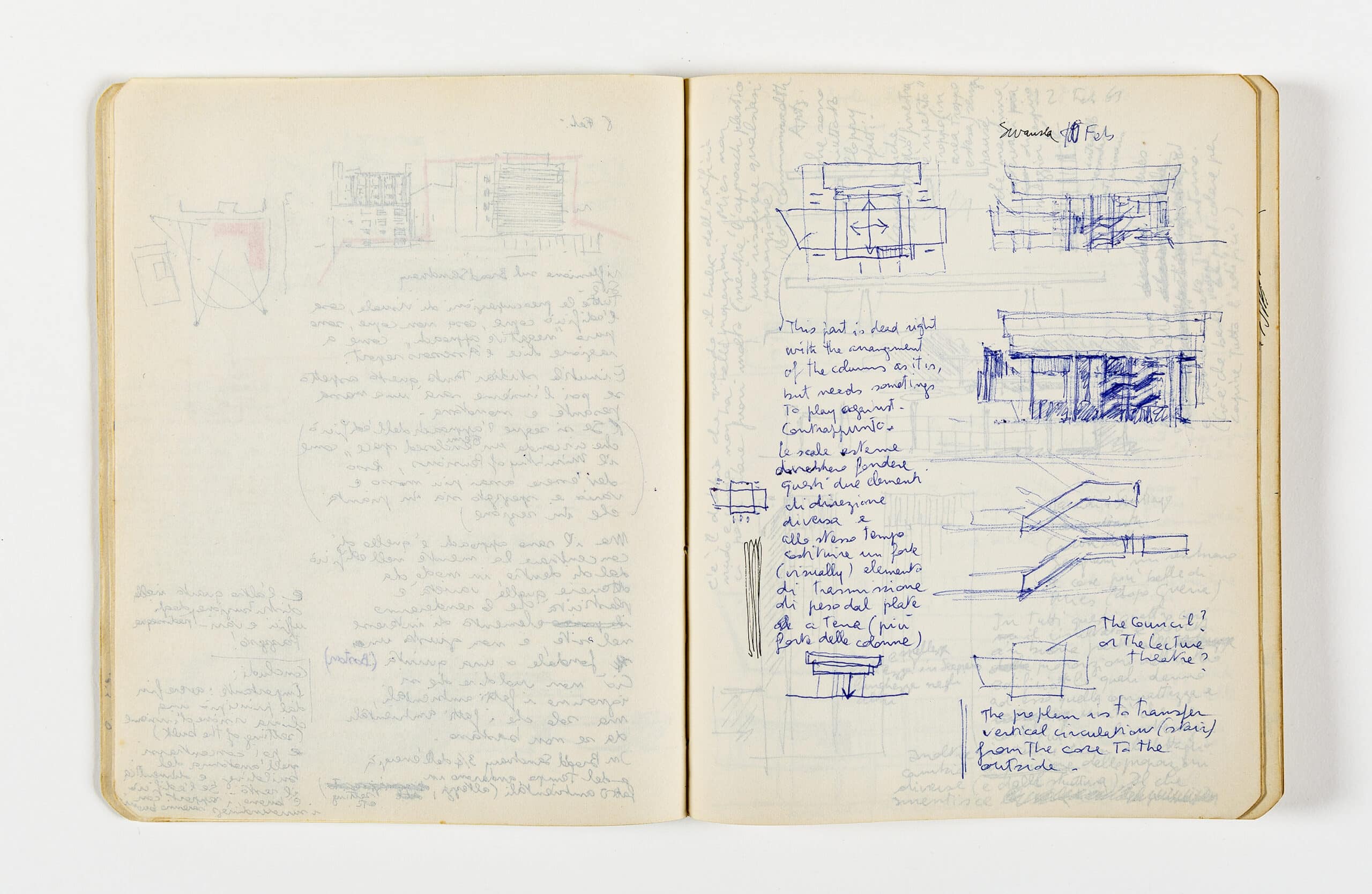

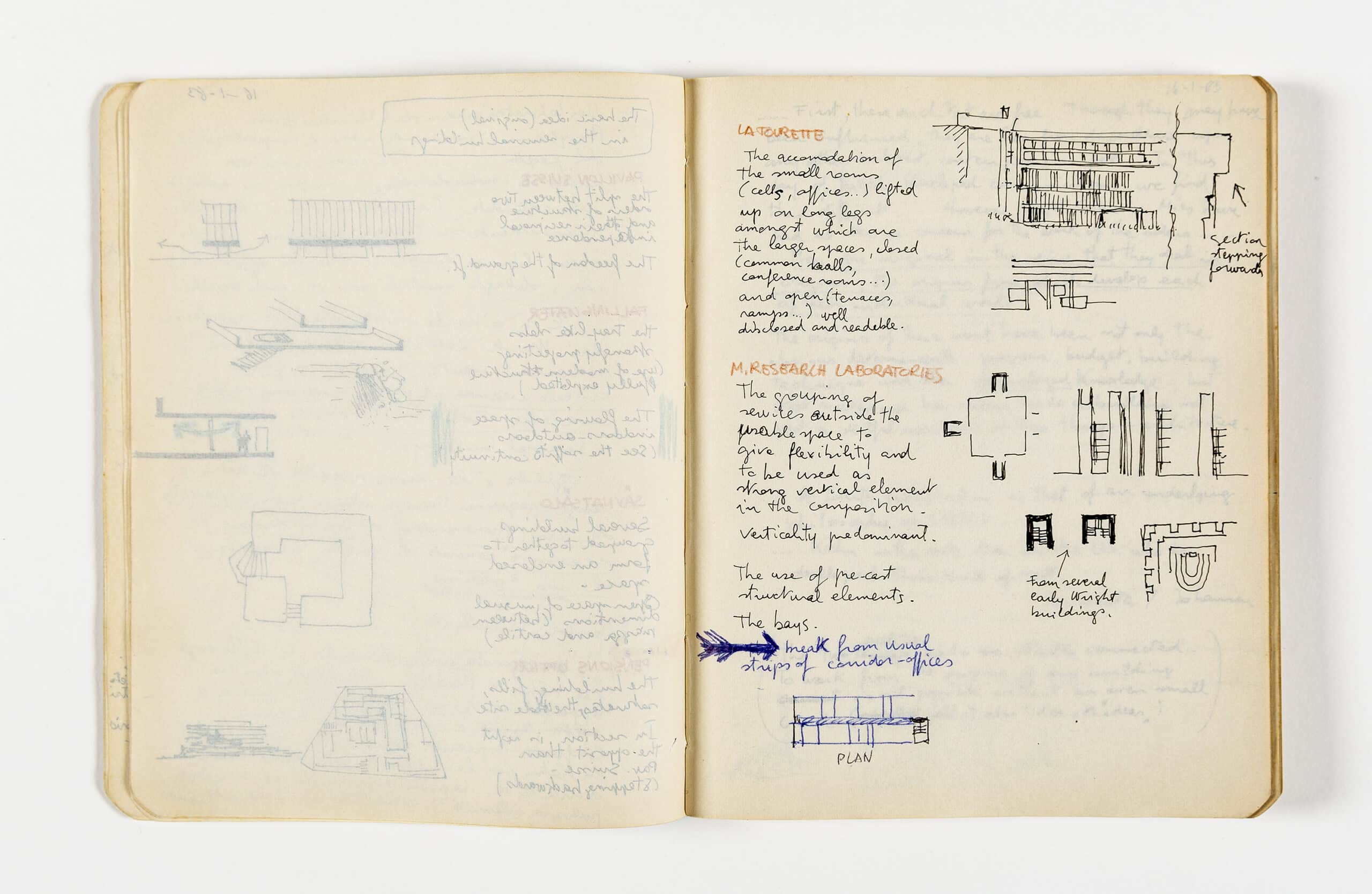

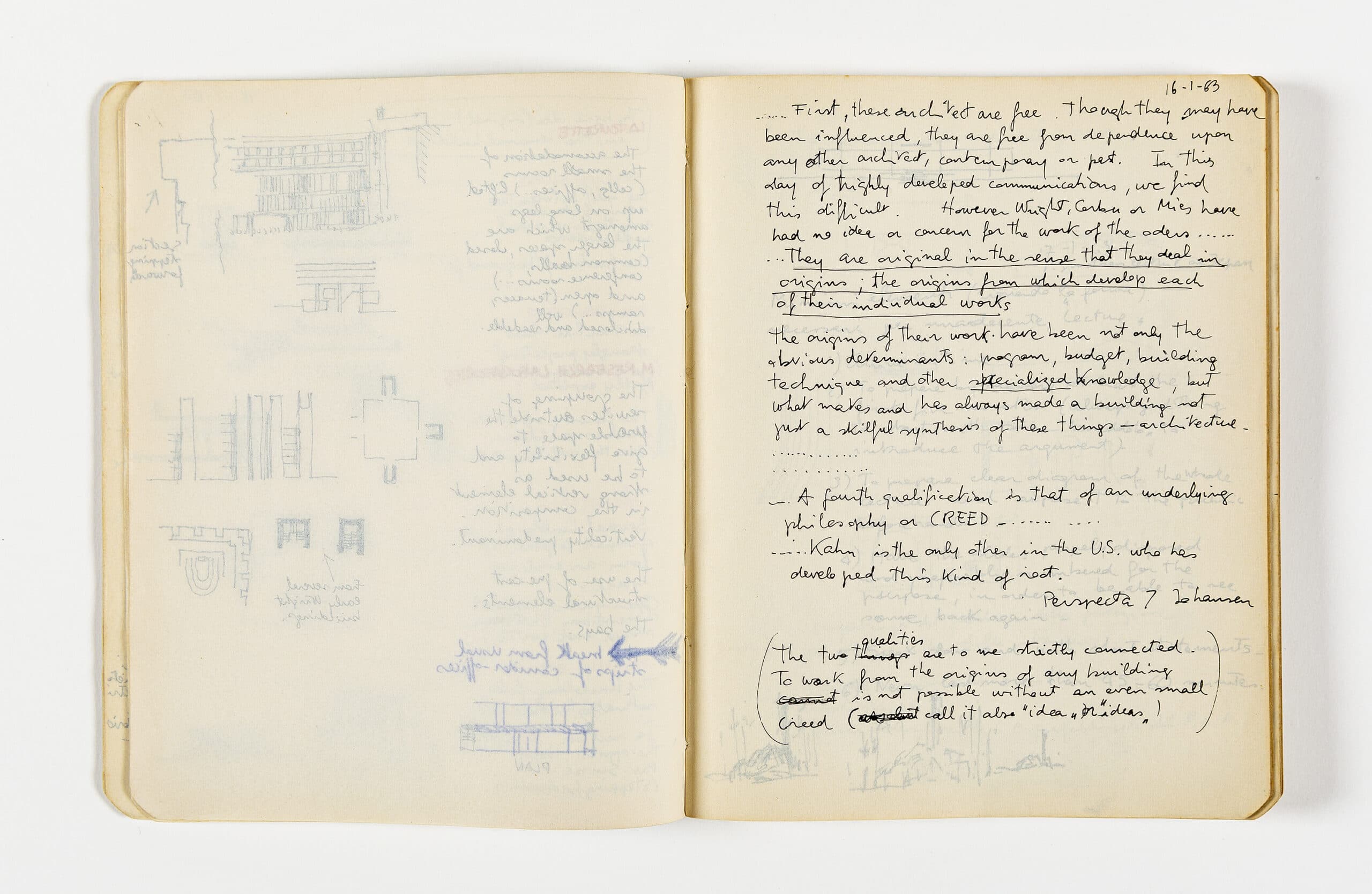

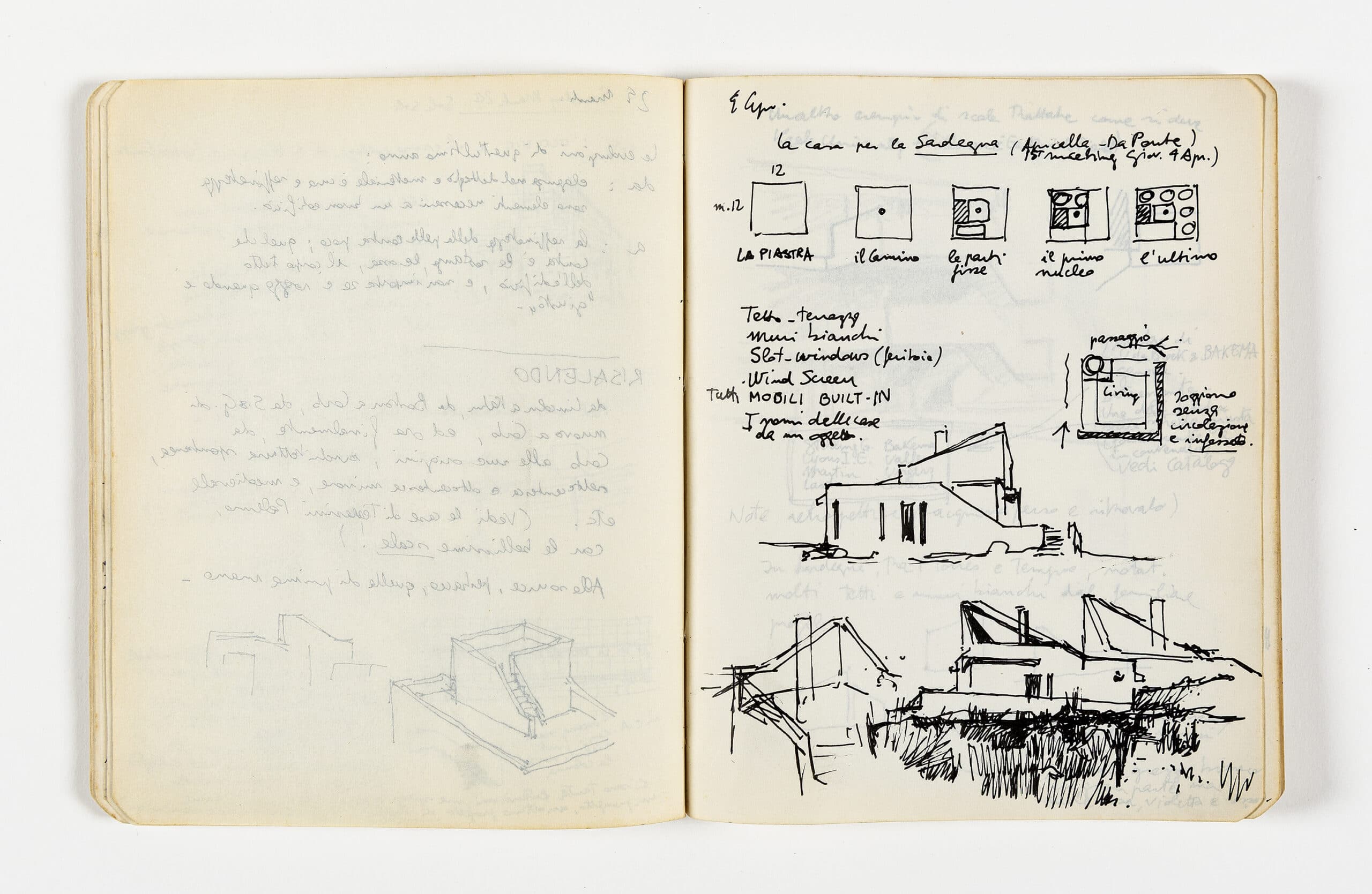

I am leafing through a neat hundred-page sketchbook with notes, the text enlivened with pencil, charcoal, and pen sketches with varied annotations, including asterisks and underlining in colour crayon, brought into order with careful lists and occasional full pages on practical matters such as delivering a lecture or taking architectural photographs. The script is comfortable and legible, initially in Italian and then, increasingly, in English, with a smattering of French, but it is Alberto Ponis’s fluent draughtsmanship that catches the eye, page after page. The sketchbook covers the early 1960s, particularly the years 1962 and 1963—the years Ponis spent in London working in Denys Lasdun’s office[Fig.01]. Sometimes we see him drawing buildings as he stands in front of them, at others reconstructing them from memory; most frequently, he has used the fine paper in the sketchbook to trace photographs from contemporary publications.[Fig.02] The opening pages offer few surprises: Ponis, a young European architect, is engaging two gears; one offers a predictable overview of the high uplands of the profession inhabited by Louis Kahn, Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, while the other is more personal, an investigative, even analytic, perspective. Yet, as I am turning the pages new aspects of Ponis’s experimental work, his drawing technique, theoretical deliberations, and travel sketches inform each other and open up new ways of seeing and analysing his sketchbook.

The sketchbook details Ponis’s time in London, where he moved after his education in Italy. Born in Genoa in 1933, Alberto Ponis was an engineer’s son, described as a profoundly intuitive man, who had designed and patented a novel weaving loom on the strength of which he set up MITA (Manifattura Italiana Tappeti Artistici) in Genova Nervi, just outside Genoa, in 1926. The firm dealing in traditional knotted rugs, carpets and tapestries was still in business when Alberto embarked on his architectural career in London. Before, however, because there was no architectural school in Genoa, he moved to Florence for his studies. At the time, the mid 1950s, the school was headed by Ludovico Quaroni, whose own complex and thoughtful contribution to the important housing programme led by the National Insurance Institute (INA Casa) had recently been completed near Rome, Casa Tiburtina.[01] Rejecting rationalism and mainstream modernism according to CIAM (which had held its final meeting in 1959), a more accommodating urban structuralism was the topic of the moment for Quaroni’s students.

In his fifth year, Ponis was one of twelve students from the school chosen to visit London. He found the city a stark, yet inspiring, contrast to the Italian cities with which he was familiar. He was gripped by the ‘very different reality’ of the capital, while visually the sharp definitions and sombre palette were in acute contrast to familiar Mediterranean tones and forms. He writes:

‘When I visited London for the first time on a trip for architectural students I had won, I was transfixed. In contrast to the warm pastel colours of the Mediterranean, here I became aware of a very different reality, one which was sharply defined and for me entirely new. As soon as I had graduated, I was in no doubt as to what to do, and with my best drawings under my arm I went back to live and work there.’[2]

Determined to return, he did so on his graduation, with a varied, well-connected, list of contacts, including Hugh Casson, Jim Cadbury-Brown, and an introduction from Ernesto Rogers to his nephew. He was in his late twenties.

Alberto arrived in November 1960, a month he remembered for being one of the rainiest ever. Richard Rogers, talking volubly in Italian, was encouraging but suggested he learn English first. However, on the strength of the drawings and perhaps the influence of those contacts, he was offered a job in the London County Council architects department. As he told Jonathan Sergison, the prospect of working alongside 600 architects did not appeal to him, nor did a better paid situation in the Middlesex County Council office tempt him either.

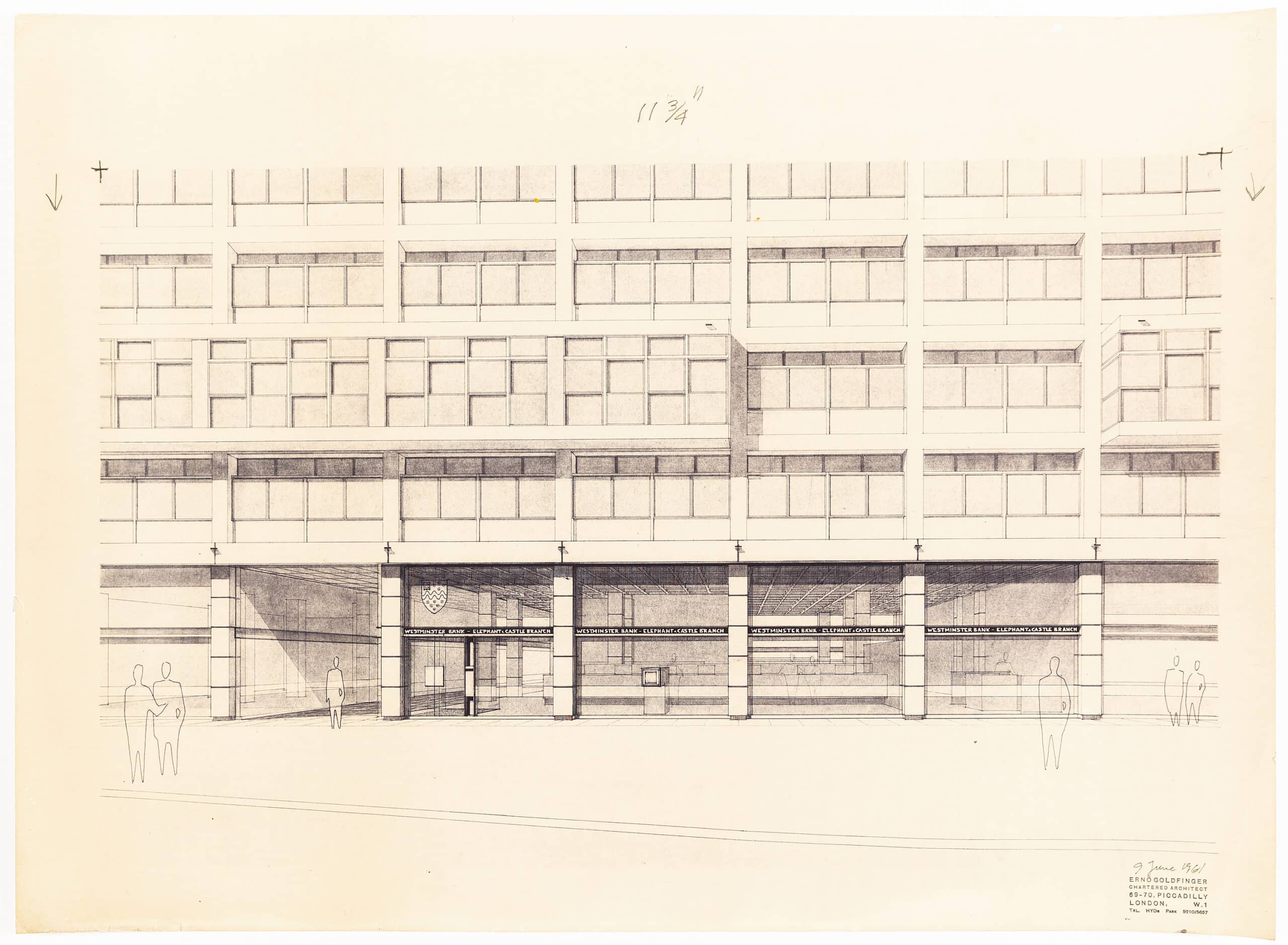

The search for a smaller practice led to Ernő Goldfinger. Although ‘a simply impossible person’, once they had begun to converse in French he became ‘quite docile even reasonable.’[3] The Goldfinger office was a linguistic (and temperamental) hurricane, but Ponis’s French brought a breath of Paris to the room and helped to soften the irascible Hungarian’s mood. There, Ponis remembers that he ‘became familiar with feet and inches, which for me were entirely new units of measurement. I learned how to use and to appreciate the modular grid, which was to serve me well in all my most complex projects in the future.’[4]

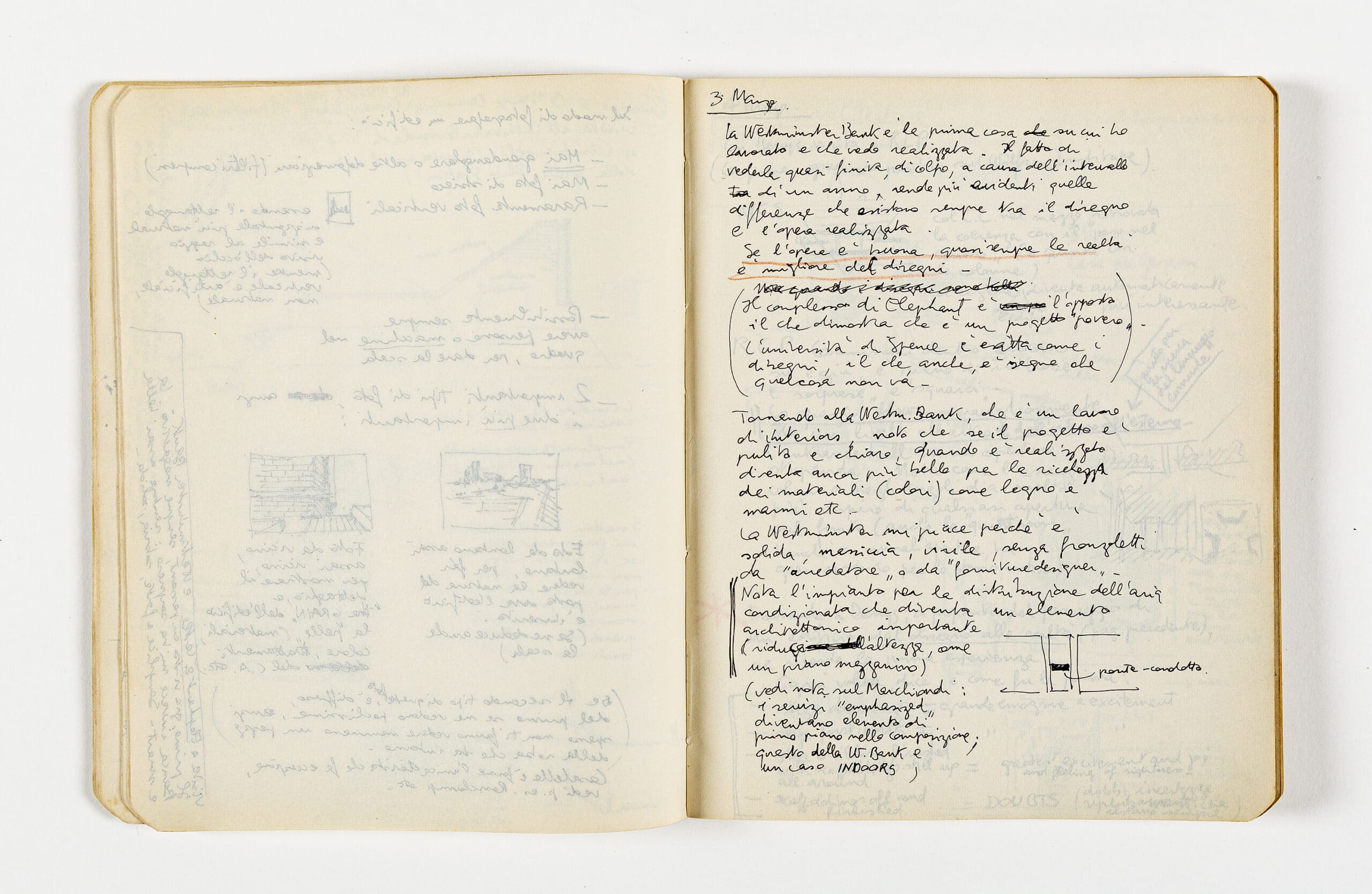

The Goldfinger office was in Dover Street, and there Ponis drew plans and perspectives for offices and shops, including the Air France building on Piccadilly. He adopted Imperial measurements and mastered Goldfinger’s obligatory modular grid. The Elephant redevelopment was the major commission in the office in 1961. However, he got considerable satisfaction seeing his own contribution, the Westminster Bank branch, completed. It was the first of his own jobs he had seen through, though his input was confined to the interiors. He noted, in Italian ‘if the work is of good quality the reality will be better than the designs might suggest’. He continued ‘The Westminster satisfied me because it was solid, virile, without superfluous decoration’[Fig.03]. He was also sympathetic to the honest expression of elements such as air conditioning, as internal features, and the importance of light and clean spaces to better show off the tones of wood or marble. Set against the disappointing Elephant complex (‘progetto povero’) he viewed his own contribution with a measure of pride.

The transformative moment came in early 1962, when Ponis joined Denys Lasdun’s practice. Having been inspired by a glimpse of the (widely publicised) St James apartments by Green Park, he decided to apply to Lasdun’s office. At his interview, in late 1961, he learned that the practice was about to move, but he was invited to join in January. The new Queen Anne Street offices, in his memory at least, were sunnier in mood and considerably more collaborative in practice than those in Dover Street. So when Ponis joined, he quickly made life friends with the core group in the Lasdun office. He now became intensely aware of the currents in new British architecture, notably the work of Stirling and Gowan [Fig.04]. While he was immersed in the proposed Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) he recalls that Charlotte Baden-Powell was working on a Liverpool swimming pool (the University sports centre), Michael Brawne on a tower in Cambridge (the unbuilt Science Laboratories on the New Museums site) and Ted Cullinan was occupied on the University of East Anglia (UEA) campus in Norwich. Their happy hours of friendly disagreement hinged on knotty topics such as detail, Brawne arguing they were essential, Cullinan ‘secondary to the bones’[5]. Alberto remembers his time in the office and the influence on his work:

‘The energy which this experience gave me went far beyond my daily working hours; the evenings and the weekends were also opportunities for entering competitions such as those for the Ministry of Works and the Museum of Ulster; I won two second prizes, which had they been first prizes would probably have altered the rest of this story.’[6]

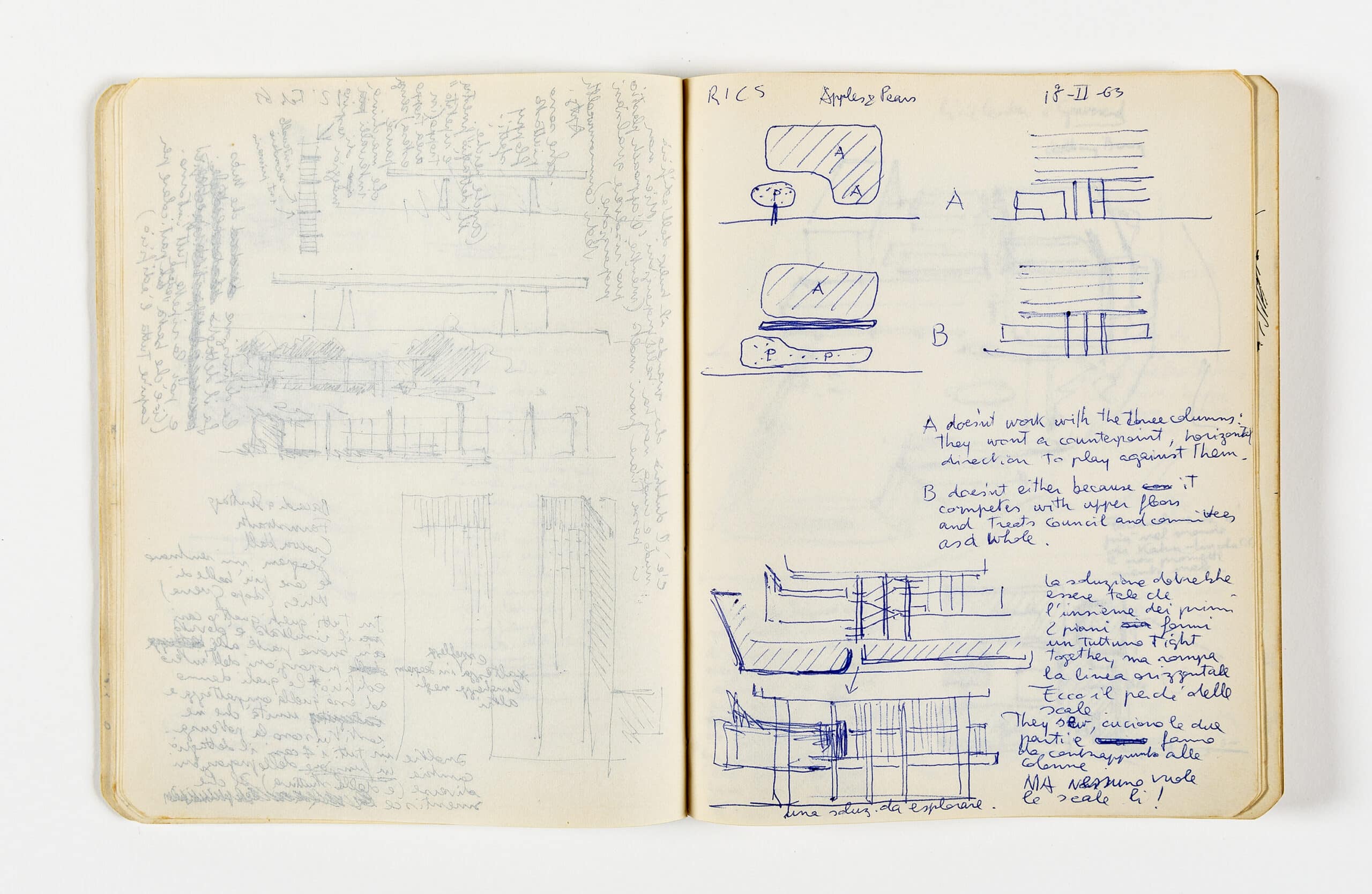

Since Ponis was not registered as an architect in the UK he could not do working drawings and, as he put it wryly, ‘this limitation became a privilege’. With a role bounded by the production of sketches, drawings and models, the tools for the putative design, his workload generated ‘very intense engagement’ as he told Jonathan Sergison.[7] At times his heroes came to life as when he heard Louis Kahn talk at the RIBA 14 March 1962. Increasingly he was able to be far more closely involved in the gestation of a project and this came to a head with the RICS scheme of 1962-63. The notes in the sketchbook, all dating from mid-February 1963 demonstrate the thinking, covering two variants of the disposition of the entry to the new building on site which Ponis heads ‘Apples & Pears’.[Fig.05] Neither works in his opinion. He then sketches alternatives, returning to Italian for his ideas relating to the disposition of columns and horizontal elements which would provide a suitable counterpoint, the ‘contrappunto’ they were seeking. He had inserted stairs but was not winning the argument (‘nessuno vuole le scale li’!) At this stage, Lasdun seems to be handing this elevation to Ponis for his ideas on the resolution. It must have been both terrifying and heady and the drawings demonstrate the effort he was making to master a transition between internal and external circulation, but always with the dominant columns.[Fig.06]

Readying himself for what turned out to be weeks of intensive immersion in the RICS headquarters scheme, Ponis returned home for Christmas and used the opportunity to take a speedy study tour en route. He returned to Nervi via Paris and Lyons, starting with a circuit of key Corbusier buildings, ranging from the Villa Savoye to La Tourette, where he muses on the grey and ‘chiaro-chiaro’ of the cement. Back in northern Italy, he visited Magistretti’s house in the pinewoods, and golf club, and Vittoriano Vigano’s house for an artist on Lake Garda. But the elegance of Italian modernism in the landscape was challenged by his admiration for the worldly Instituto Marchiondi, Milan, with fenestration punched through and recessed into a tough concrete fabric, all on a grand scale. He had not yet visited the widely admired building but drew it when he was immersed in the office and the RICS, late in February. He was, for now at least, eager for expressive urbanity in architecture on the Brutalist model.

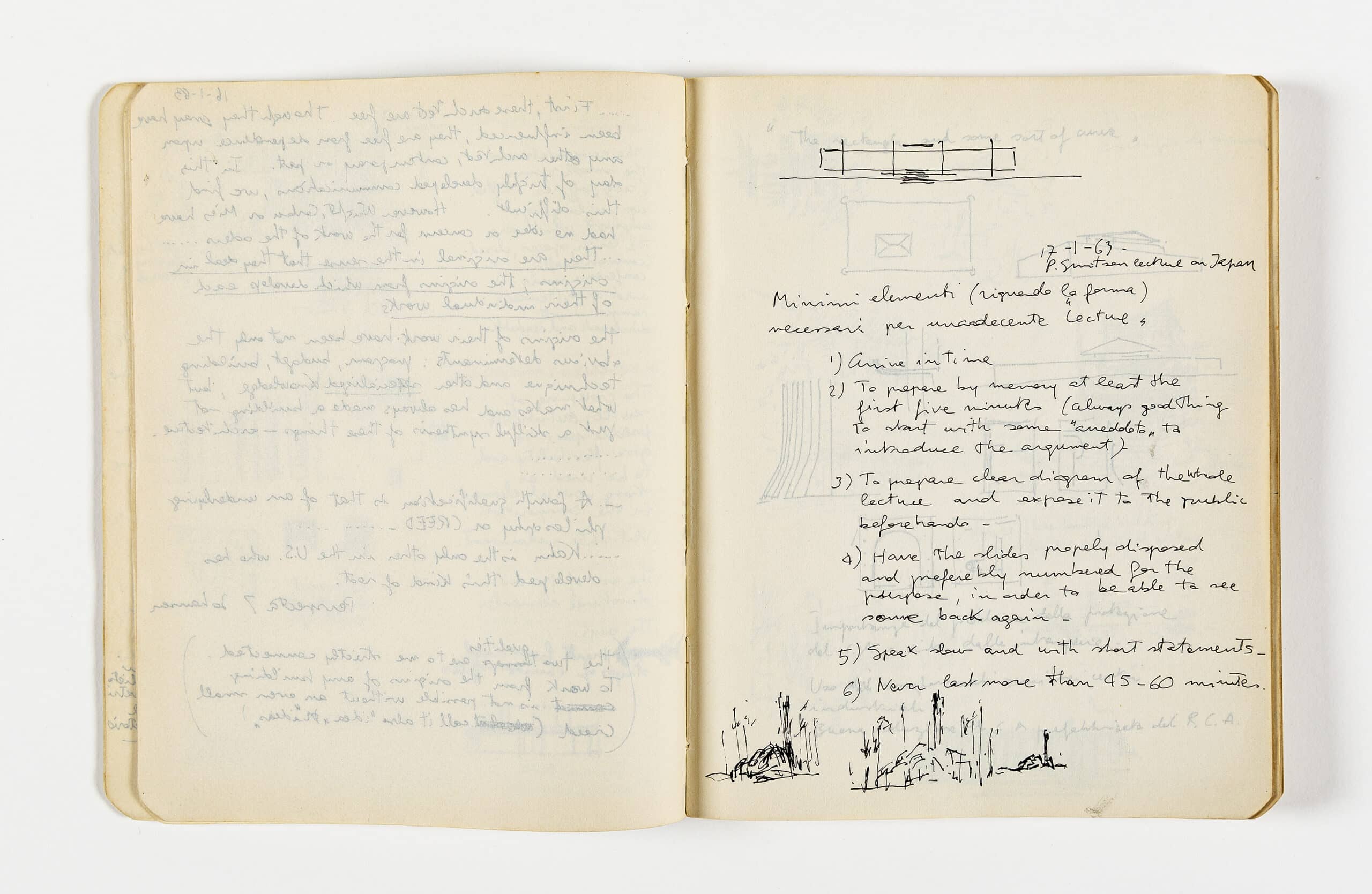

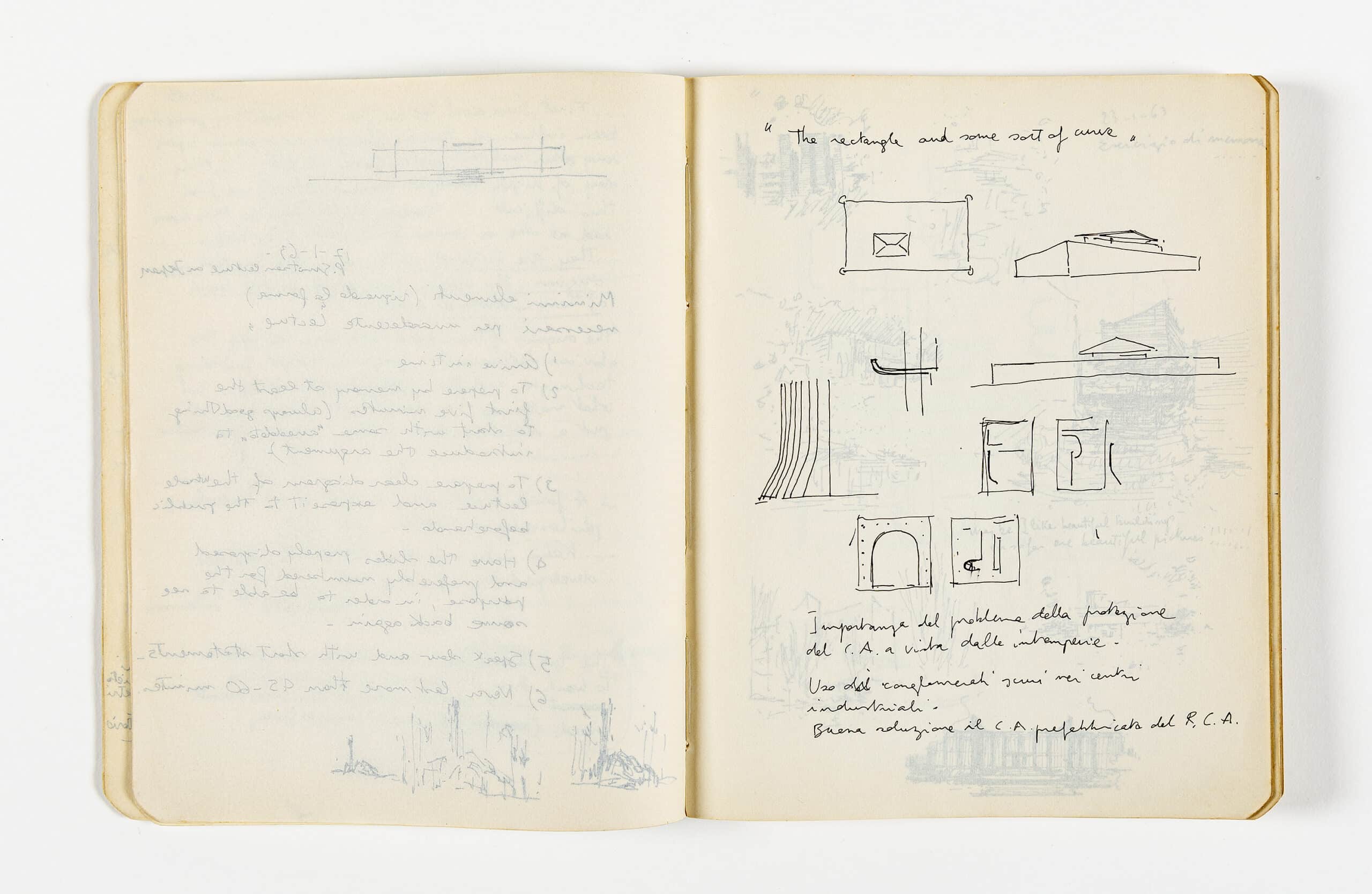

To stimulate his ideas on the topic he attended a lecture on Japan by Peter Smithson, perhaps tipped off by the practice secretary, who had become his wife in early 1963. It was ‘Form Above All’ (the first part subtitled ‘The Rectangular Plane and a Certain Sort of Curve’, the second ‘Object Making and Place Making’)[8] given as the Michael Ventris Memorial Award Lecture at the Architectural Association. Ponis used the opportunity to make notes on how to present a lecture, along with some sketches and annotations,[Fig.07,08] rather than to transcribe Smithson’s dense rumination on Japanese architecture. The man in whose memory the intense lecture was given was the late young architect Michael Ventris, who had also, spectacularly, deciphered the cuneiform script.

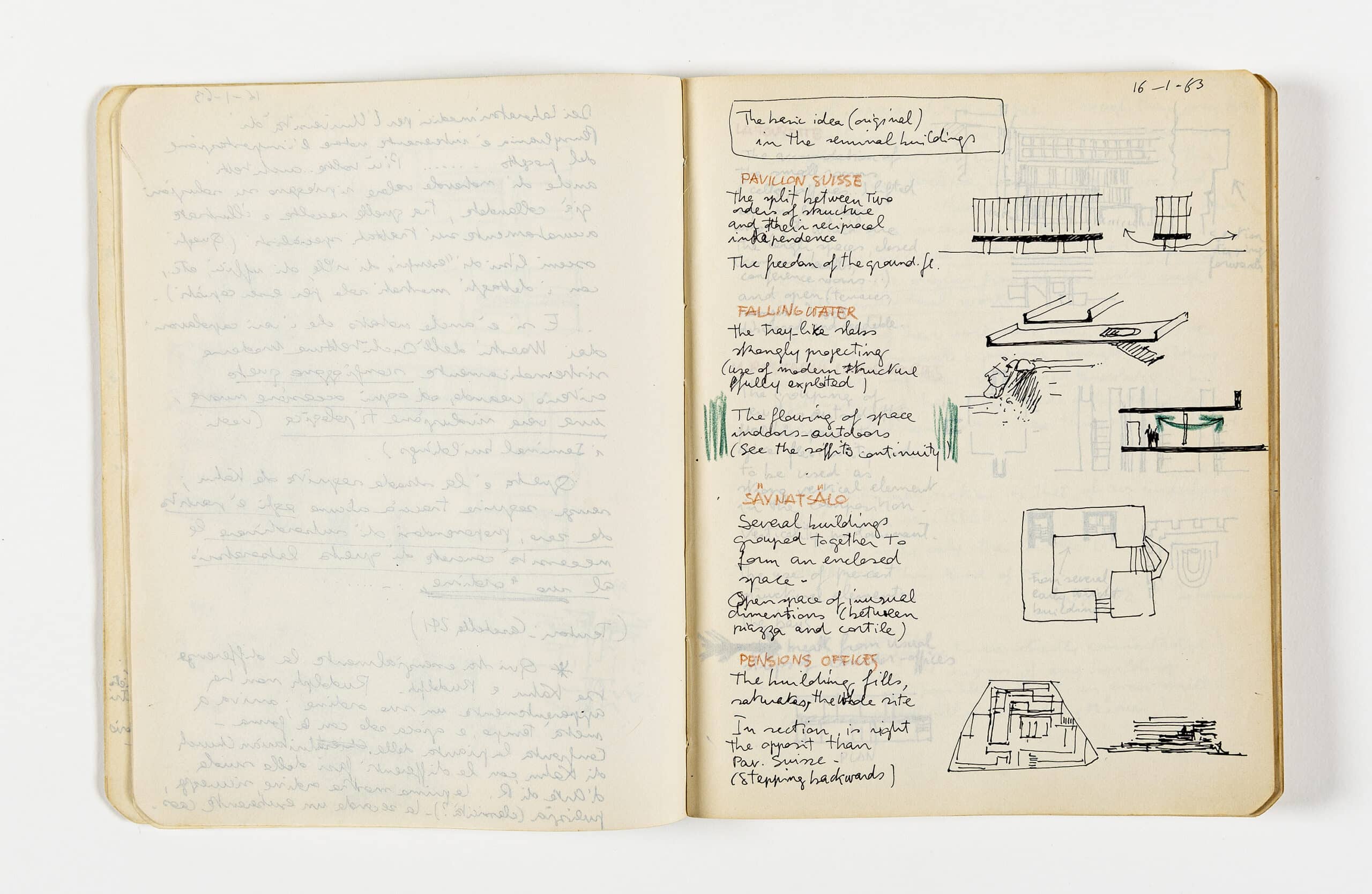

As he pondered the literature, quoting from John Johansen in Perspecta 7, presumably as a relief from office routine, he noted a series of generic forms, exemplified by key buildings from his architectural heroes.[Fig.09,10] The Pavilion Suisse was his chosen example of space flowing below buildings while Falling Water exploited modern structure with ‘tray-like slabs strongly projecting’. From Aalto (Saynatsalo) he took the grouping of disparate buildings which mark out an enclosed core of ‘unusual dimensions’ in contrast to the same architect’s Pensions Offices where the building entirely fills the site. Then he considered multiples, at La Tourette, where cells or offices form the background to larger spaces, interiors, or external terracing, ‘well disclosed and readable’ as he put it. Finally, he remarks on the flexibility achieved by the use of external services, the emphasis on verticality and the use of precast structural elements in Kahn’s Research Laboratories. In summary, he writes, excitedly, ‘…these architects are free. Though they may have been influenced, they are free from dependence on any other architect, contemporary or past.’ They deal in origins and so ‘they are original’. The result is architecture and ‘an underlying philosophy or CREED’. Further, ‘to work from the origins of any building is not possible without an even small creed (call it also ‘idea or ideas’!).[Fig.11]

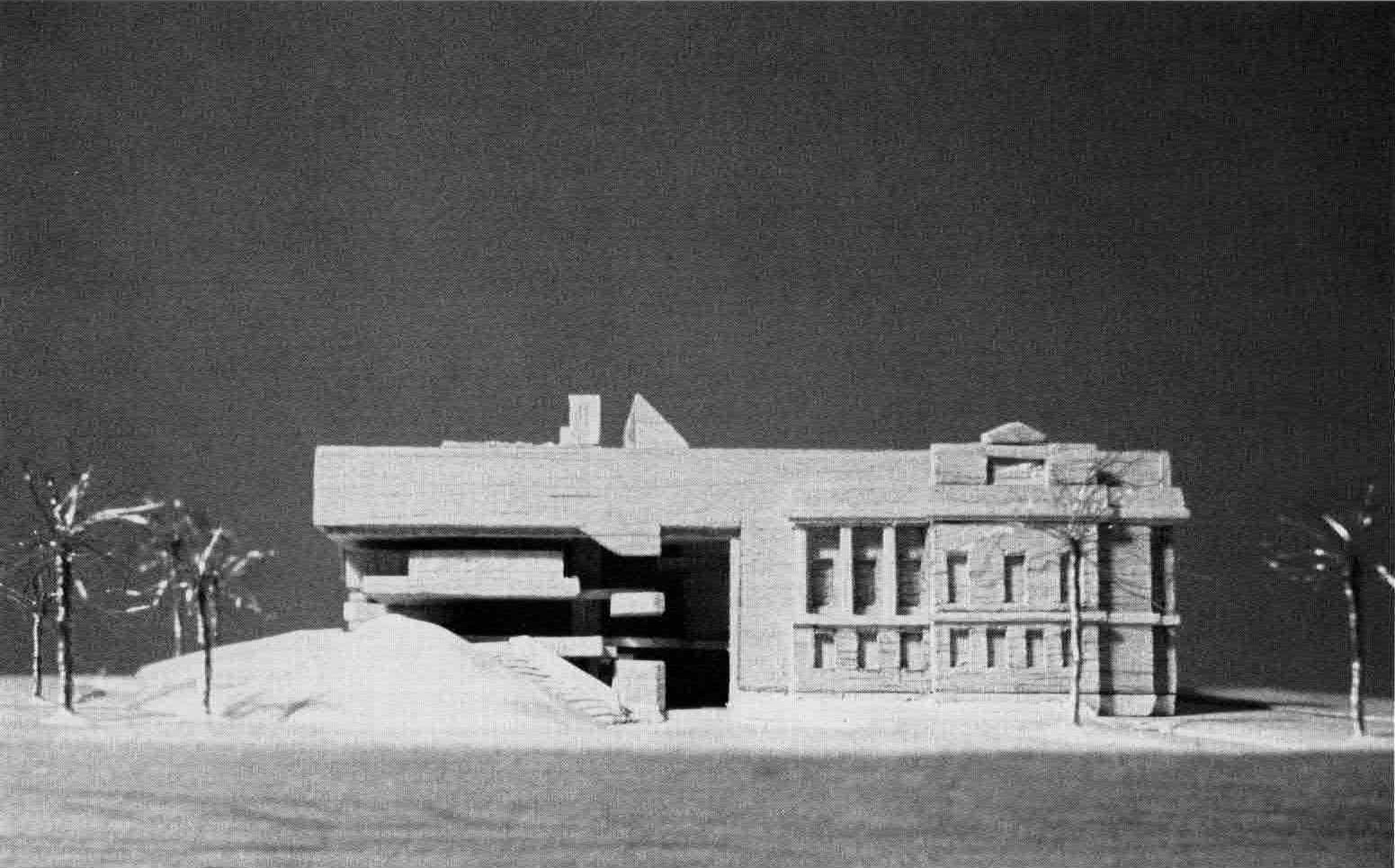

When Alberto Ponis and Charlotte Baden-Powell entered the competition for the Museum of Ulster in 1962, submitting a remarkably handsome model, and took second place, the design shared several features with both the proposed RICS and the just completed Royal College of Physicians such as the heavily modelled and recessed, even punched out, elements, the marked strata of levels within the building and an appropriate attention, while maintaining independence, to neighbouring buildings of markedly different age and character.

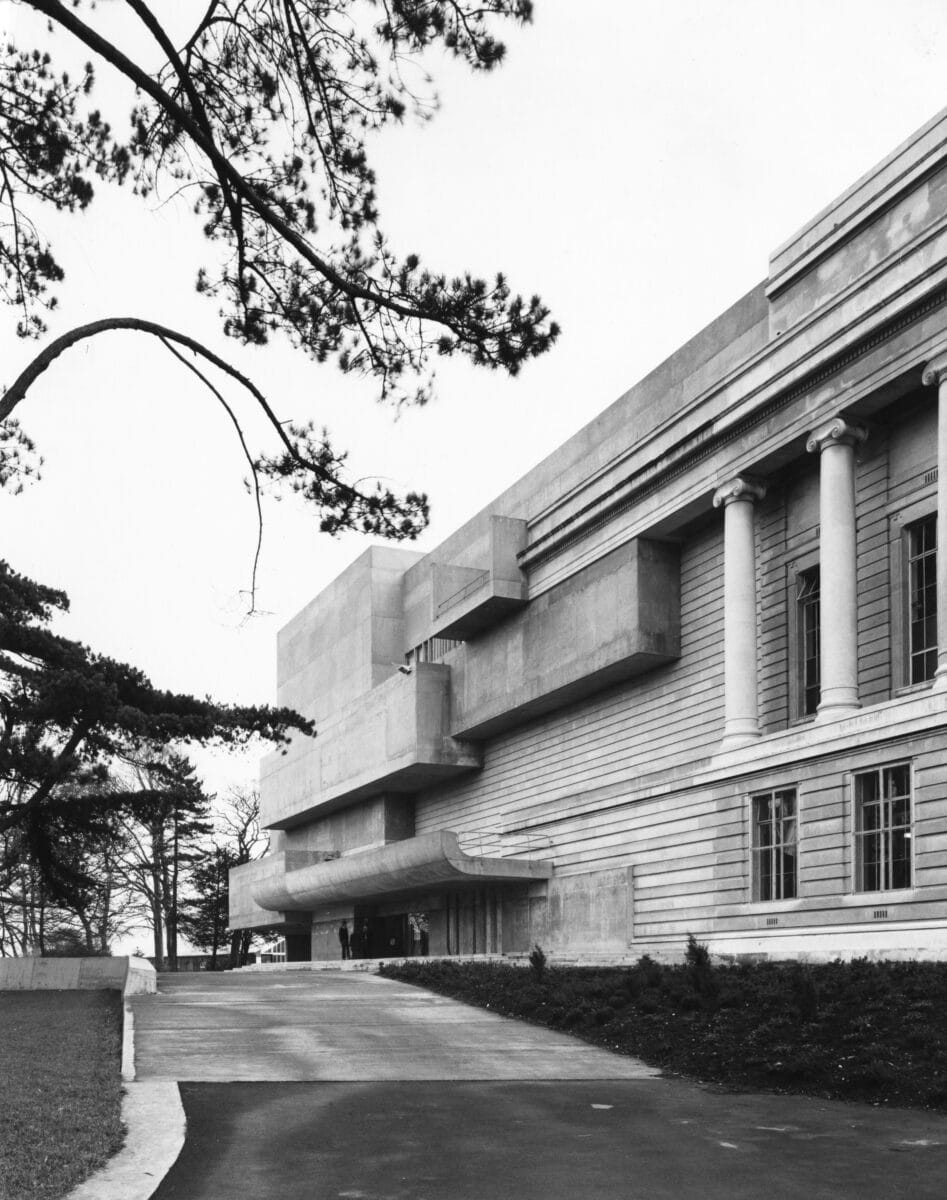

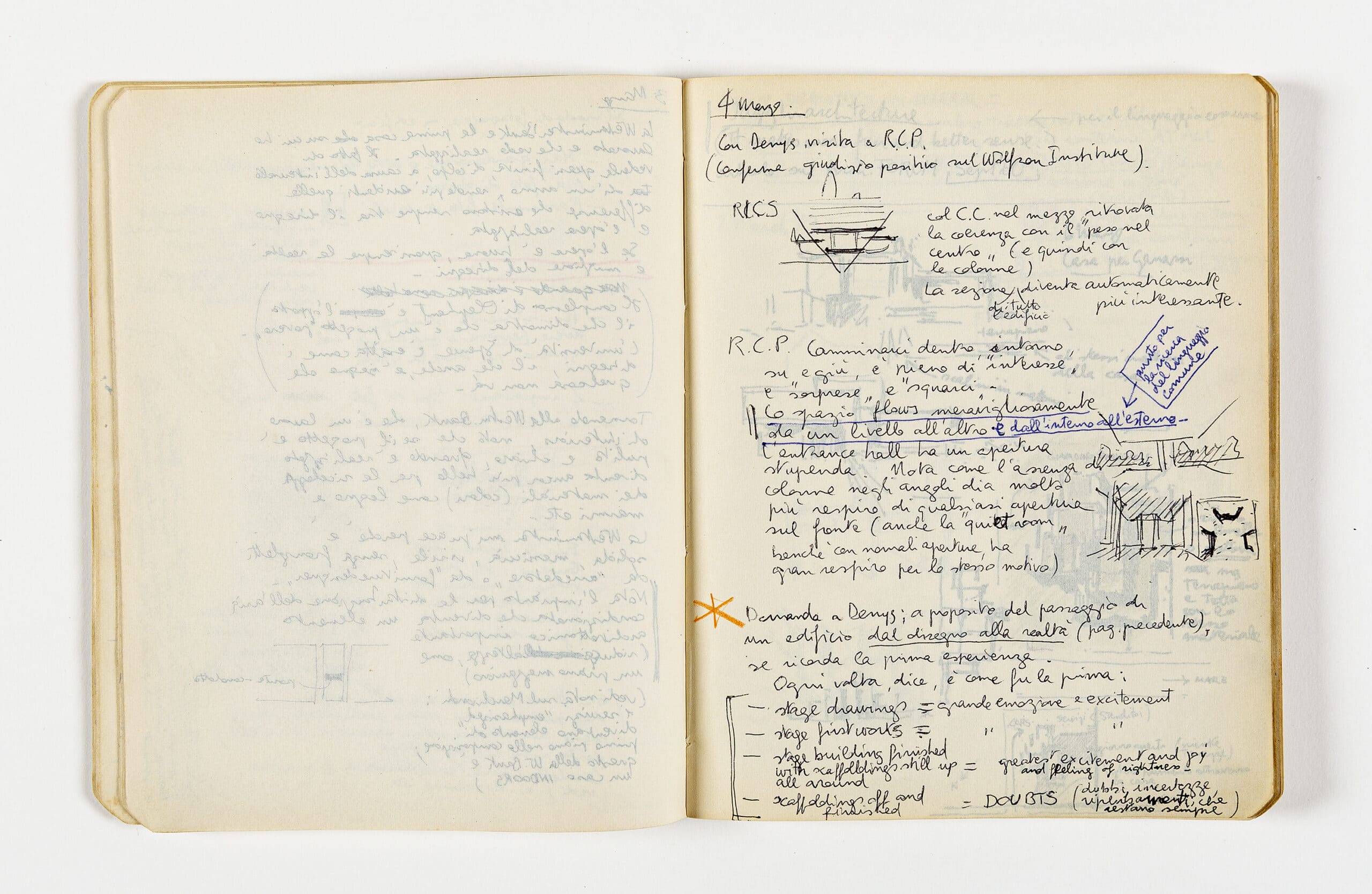

On one memorable day, March 4, 1963 Ponis visited the Royal College of Physicians with Lasdun, a mark of their growing familiarity. They discussed it and their admiration for the Wolfson Institute in Hammersmith, a job by Lyons Israel Ellis. Ponis had been struck by the ‘chiara e economica’ distribution of space—concentrating on levels and stairs. They discussed the passage of a building from design to reality … ending with ‘DOUBTS’.[Fig.12]

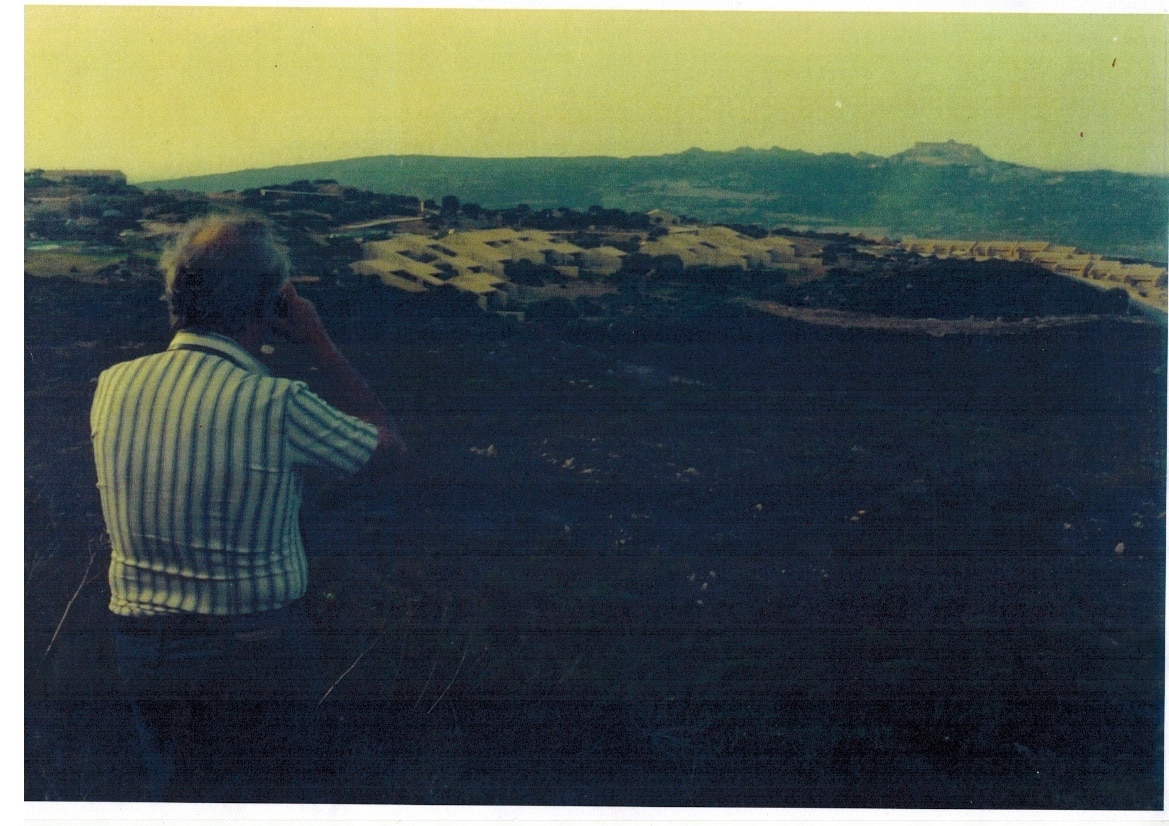

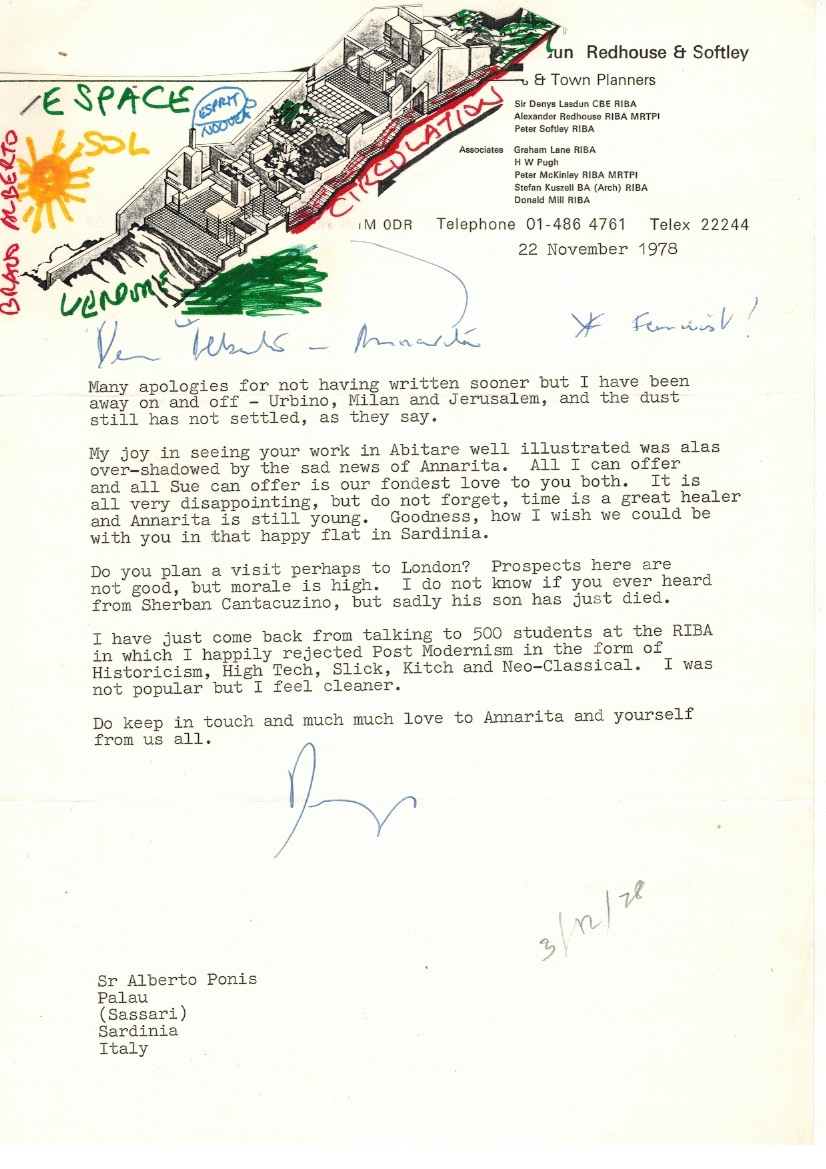

In 1963, Ponis recalled the exultant mood in Lasdun’s office when the news of the National Theatre commission came through, (at this stage to be combined with an opera house) and located on a site alongside the Festival Hall. This euphoric atmosphere, a welcome relief from the many difficulties around the RICS project, encouraged Ponis to tell Lasdun that he had been offered a commission in Sardinia.[Fig.13] Generously, Lasdun gave him a fortnight off to pursue it. His debt to Lasdun’s unquestioning release that spring led to a lasting friendship between the two men and their families. With his attention turned to Italy, where his London-based Italian restaurateur friend Enzo Apicella offered him an opportunity to design a house amongst the punishing, but beautiful, rocky landforms of north Sardinia, Ponis travelled between Italy and London for the next two years. In the coming two decades he moved away from mainstream modernism and became ‘rooted in location’, that of the rock-bound coast and Sardinian uplands.

But despite the move to Italy, Ponis remained closely connected to his former office and continuing relationship with Lasdun. Writing in early January 1977, Lasdun happily looks ahead to a meeting between them after many years; they will ‘talk into the early hours about life, architecture and the future.’ There was to be another fruitful period after that, a last act, perhaps a decision taken in one of those late-night conversations in Sardinia. They collaborated on the competition entry for the Teatro San Felice in Genoa in 1980-81, the opera house which had been substantially destroyed by allied bombing. Lasdun and Ponis’s entry retained the strong portal but then softened into a layered, stratified form with a great courtyard at the heart. It came second, after Carlo Scarpa’s death, to Aldo Rossi’s entry. In August 1983 Lasdun wrote to Ponis, ‘I wish you would destroy all those awful colour drawings of the opera house.’ Perhaps he feared that coloured drawings gave him a postmodern taint? The final decision, people said, was strongly political which can hardly have been a surprise.

To download a PDF of the correspondence between Ponis and Lasdun from 1977 to 1983 click here.

Notes

- Vittorio Gregotti, New Dictionary in Italian Architecture (New York: George Braziller, 1968), 44.

- Sebastiano Brandolini, The Inhabited Pathway: The Built Work by Alberto Ponis in Sardinia (London: Park Books, 2021), 18.

- Jonathan Sergison, ‘Alberto Ponis in conversation with Jonathan Sergison’, AA Files 73 (2016), 104.

- Ibid. Ponis gives a less positive steer, ‘I wasn’t so enthusiastic about the modular grid that he used on every single one of [his] projects.’.

- Jonathan Sergison, ‘Alberto Ponis in conversation with Jonathan Sergison’, AA Files 73 (2016), 105.

- Sebastiano Brandolini, The Inhabited Pathway: The Built Work by Alberto Ponis in Sardinia (London: Park Books, 2021), 18.

- Jonathan Sergison, ‘Alberto Ponis in conversation with Jonathan Sergison‘, AA Files 73 (2016), 105.

- Neil Jackson, Japan and the West (London: Lund Humphries, 2019), 369-70.

Gillian Darley is an architectural historian and past president of the C20 Society—‘To introduce myself, my working life has always been focused on inspiring people, intriguing buildings and beguiling landscapes.’ To read more click here.