Notes on Louis-Hippolyte Lebas’ Travel Sketchbooks (Video)

The sketchbook is your loyal private companion, your eyewitness and accomplice on voyeuristic escapes and inquisitive journeys. It is a brain in your hand, mirroring even subconscious registrations, only discovered afterwards, as you flick through the pages, absent-mindedly. You remember—much has already entered you, through the hand.

I cry when I think of all the sketchbooks that probably have been thrown away as minor scribbles, lesser works or embarrassing trash. In architecture, I would argue that most of the decisive work takes place in sketching—the rest in working out the making, through working drawings. Presentation drawings for clients often bore me stiff, except when done with the sensitivity of a Michail Papadopoulos for Sigurd Lewerentz.

The sketchbook has been the touchstone and registration tool for architects and artists for centuries—how brilliant then of art historian Ragnar Josephson in 1934 to invent a Museum of Sketches, first called The Archive Museum, with the aim of shedding light on the artistic processes. It is steadily growing.

Drawing Matter has been clever in collecting a number of these gems—of Tony Fretton, Álvaro Siza, Louis-Hippolyte Lebas—to name a few of high significance. They are like Oxo-cubes for creative broths, filled with tests, thoughts and observations. And for Lebas, for instance, he is obviously amassing a whole larder of architectural goodies, in tiny, focused fragments.

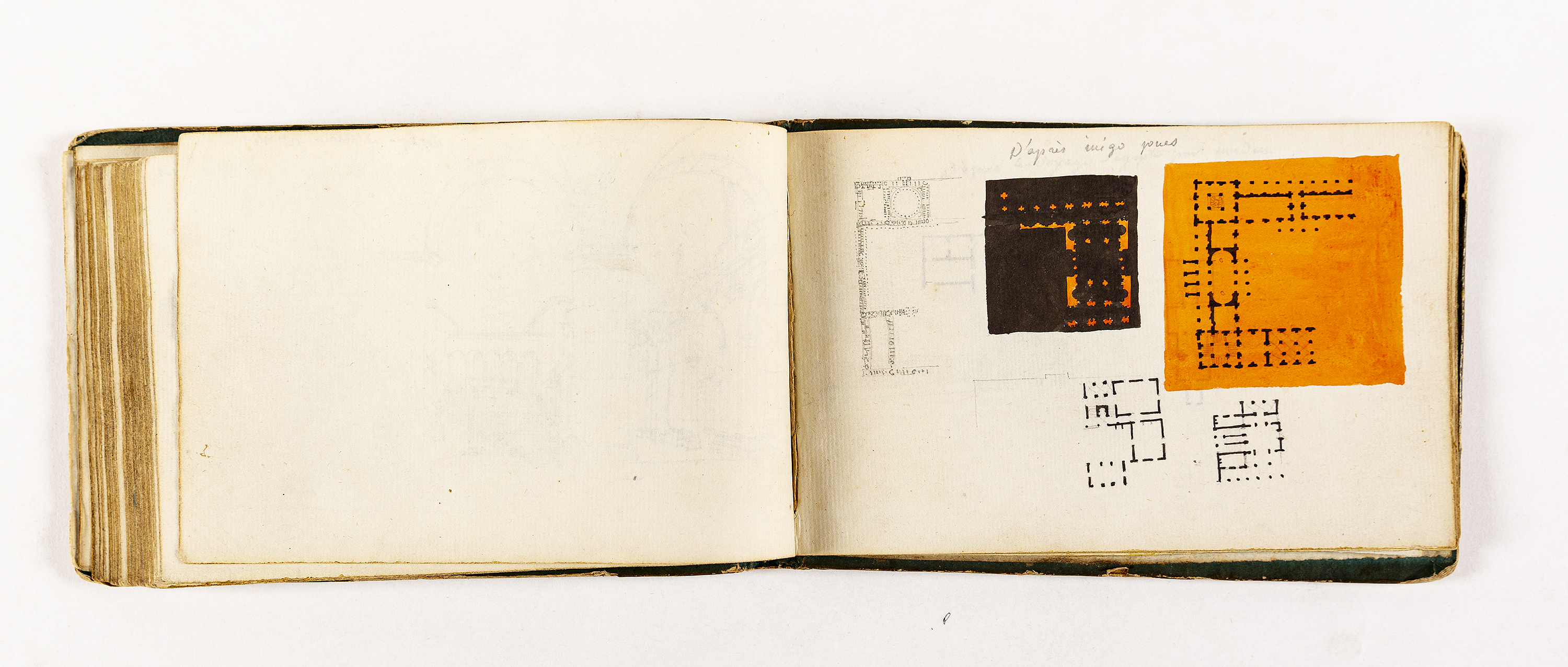

This video is a short glimpse into two of Louis-Hippolyte Lebas’ sketchbooks, from 1804, when he was just 22 and travelling in Europe. But, as you will see, he also travels in books and in other architects’ drawings. ‘After Inigo Jones’, ‘after Serlio’… He is observing, registering, amassing and drawing architectural parts, devices and fragments.

There are seldom entire plans; he only notes what he needs to explore the relation between a series of rooms, how parts come together, the negotiation of elements or the feeling of mass and void. At times, these sketches are very elaborate—like the ones of Villa d’Este. But other times he just throws down a few lines to catch the main elements, their proportions and inner order. It is often clear what he is doing and seeing, yet somehow kaleidoscopic in its collection of characters.

Many sketches seem remarkably contemporary, bold and direct—and you feel privileged coming so close to his registration of the things and places around him. It is an unequalled experience. He takes in the world, and just like in the sketchbooks of Peter Celsing some 160 years later, Lebas draws people, flowers, details, animals, plans, cornices or how shadows shape the forms in our gaze.

There is something about the sketch, I guess it has to do with its private nature, but also its lack of pretence. It is like the backside, unrehearsed, ad hoc, informal, private. The sketch was never meant to be shown—sometimes not even meant to be seen with your own eyes—rather a note you registered to be able to see better, outside of it. Brain scribbles, thought depictions, reflection lines, cognition layouts, delineations, doodles or portrayals; they are primarily designated for your own memory.

The sketches by the young Lebas are often combinations of buildings caught as a small, composed fragment, rather than whole monuments, as if the relation of architectural characters and the resulting room configurations was the focus of his observation. These found ensembles of fragments appear as fresh propositions as much as registrations, opening a timeless architectural probe, surprisingly intriguing and inviting.

1804 seems just a few days away. That is the hopeful mystery of architecture and the wonder of archives.

So, keep your sketchbooks.

And for the time being, let them retain their quiet concealment.

This video, filmed in the space of the archive, is part of an ongoing series at Drawing Matter, where we ask scholars and practitioners to look closely at and comment on particular drawings, sketchbooks, and artefacts in the collection.

*

Elizabeth Bonde Hatz is an architect, professor and art curator based in Stockholm. She exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018 and was part of the 2023 Irish pavilion. Her writings include texts on Peter Märkli, Hugh Strange, Paulo Providencia, Grafton Architects, Robin Walker and Vilhelm Hammershøi. In 2021, Hatz was awarded the Architecture Prize at the Royal Scottish Academy.

* After watching the video and reading this post, architect Robert Barnes contacted us to note that the building sketched by Inigo Jones is the Palace of Westminster Project.

– Nicholas Olsberg