Gathered Moments: Asplund’s Villa Snellman

Virginia Woolf’s use of short stories to form larger works, and her bracketing of inner discourse with physical objects and phenomena, suggest a similar episodic approach to architectural composition. Discrete moments are assembled to form a whole which is often held within an overarching temporal structure. This structure does not determine the identity of each part but gathers each in proximity. The moment might last for the duration that a building stands or could be as fleeting as the place created by a pool of light from a lamp as it is turned on and off.

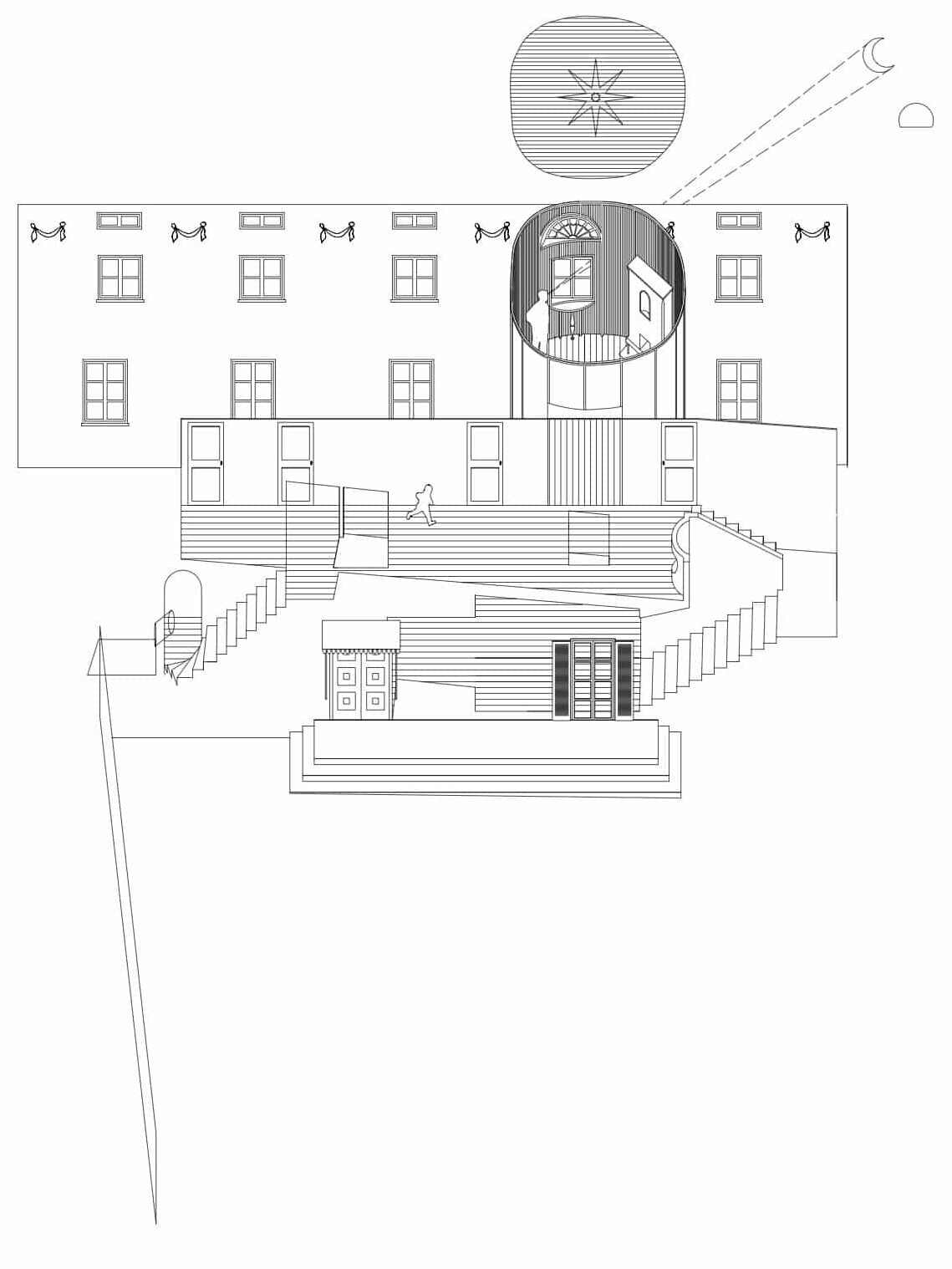

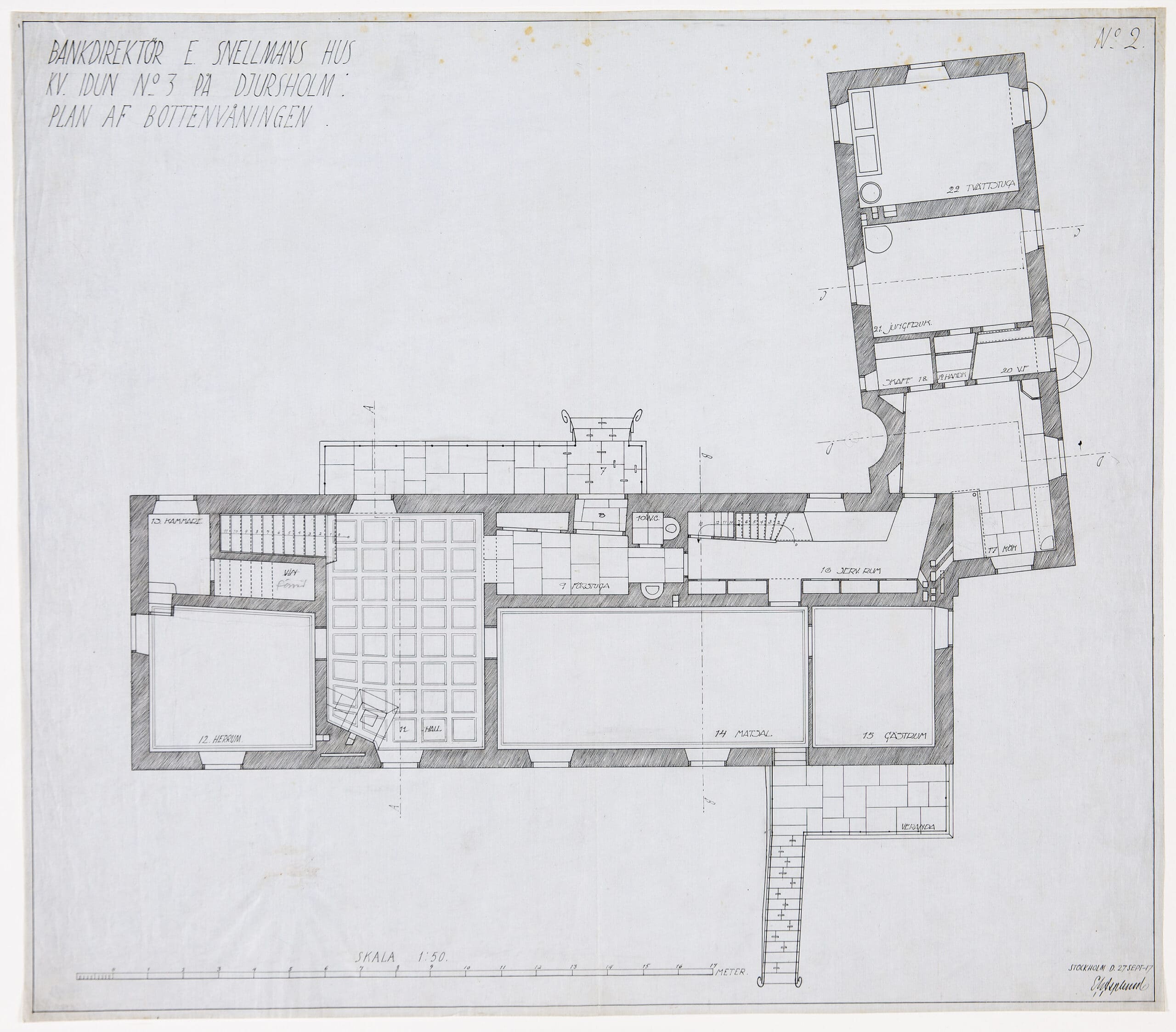

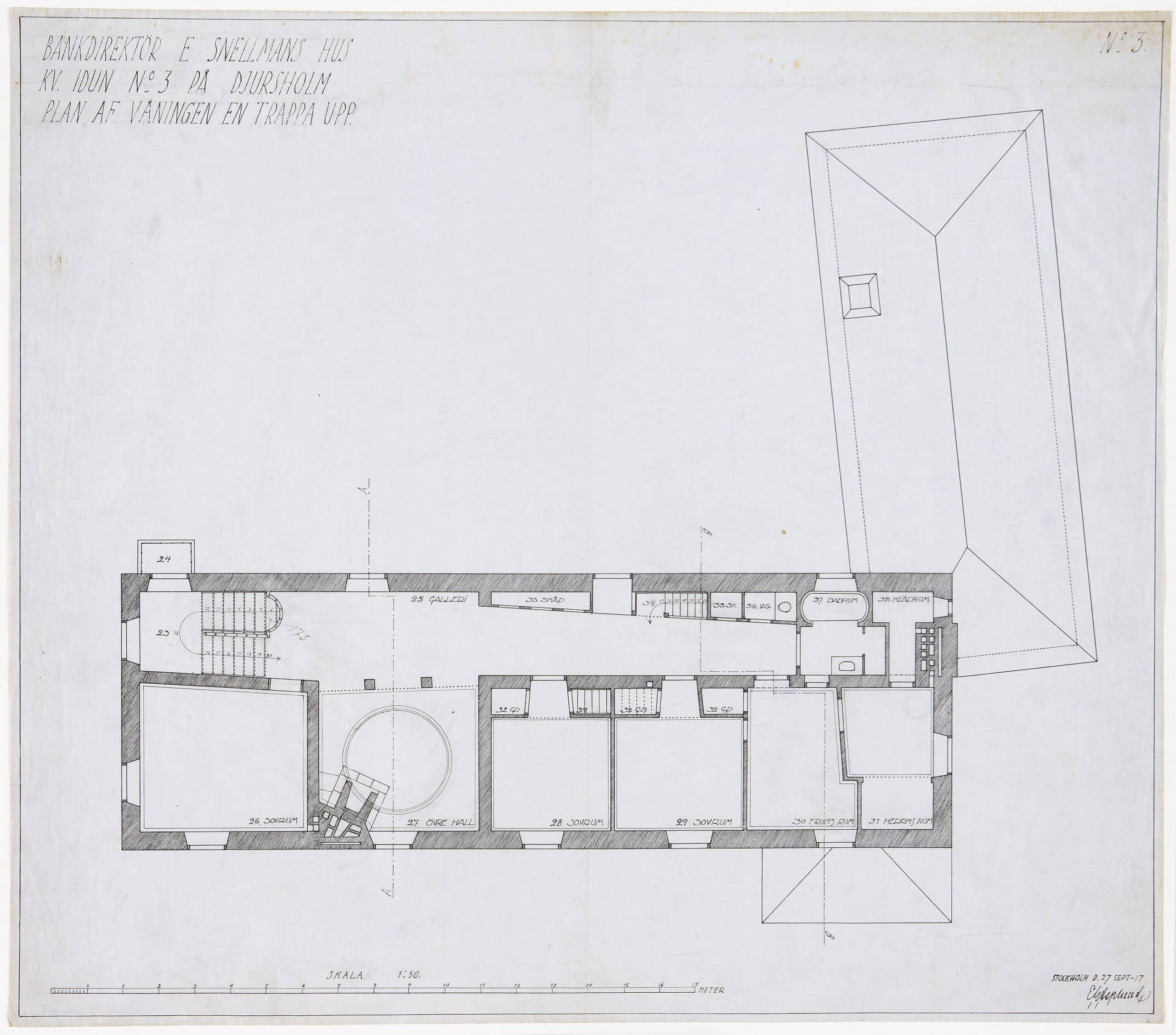

More contemporary with Woolf than the present, the Villa Snellman was built in 1917–18 in Djursholm, Stockholm. Designed by Erik Gunnar Asplund, it embodies an episodic approach to composition. The simple two storey high rectangular volume of the house ‘holds together’ an assemblage of unexpected individual episodes and incidents where one part does not necessarily relate directly to another. The diverse spaces of the house read as a collection of short stories contained in a single volume, much like Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, which would be published four years later.

A restrained, modest entrance facade conceals a complex, unpredictable interior. The entrance facade is flanked by a lower service wing and includes two doorways joined by a stepped plinth. Moving through a doorway in this facade visitors enter a tapered hallway, surprisingly non-parallel to the facade they have just passed through. Culminating in a staircase with a half landing, which itself tapers in another direction, the space continues upstairs where the varying thickness of the tapered facade wall, created by cupboards and a secondary staircase, can be read in the depth of a landing window. Amongst a series of closed doors along the landing wall is another opening which leads to another surprise—an ‘upper hall’ formed from a curved space lined with timber. Here, juxtaposed with a stove and awkwardly offset in the facing wall is a window, which when viewed from the garden, does not line up with the other windows as you might expect. Both this window and another half circle one above—the only one in the house—face south-west to receive the sunset and fading light as the family gather for evening prayers.

This single trajectory—which will also be punctuated by a coterie of other objects and conditions, like the curved table ledge below the window, the warmth of the stove and comfort of a chair—is limited to one point of view. When other trajectories are considered, and the rest of the household become involved, a string of individual moments and points of view gather and entangle as the family dwell from day to day in the world created by the home. A multiplicity of intertwined narratives is written by each resident-author—all bracketed by the episodes of the house. Each of these individual, interior incidents are contained by the modest exterior and rectangular form that hold them together.

Excerpted from Andrew Carr, ‘Cathedrals on the light of a butterfly’s wings: the momentary architecture of Virginia Woolf’, Arq: Architectural Research Quarterly, 27(1) (2023). doi:10.1017/S1359135523000088. Read the full article here.