Gavin Stamp: Interwar, British Architecture 1919-1939

When the architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner was asked to draw up an inventory of interwar buildings that deserved to be placed on the Statutory List, the so-called ‘Pevsner 50’ that resulted was almost entirely composed of the whitest of white modernist buildings. Similarly, John Summerson argued that the only thing worth writing about the period was the rise of the Modern Movement. Such approaches provided a harmfully skewered portrait of an age where modernist architecture only ever counted for a tiny proportion of actual building. The Thirties Society was founded in 1979 to counter such procrustean tendencies.

Gavin Stamp’s Interwar, British Architecture 1919-1939 is the culmination of a lifetime’s fervent advocacy and deep knowledge of the architecture of this period. Although he published a moving account of Lutyens’s Thiepval, a special issue of Architectural Design on ‘Britain in the Thirties’, and a hilariously barbed celebration of neo-Tudor, his foremost output was in heritage campaigns, not least as John Betjeman’s successor as Private Eye’s Piloti and as chairman of the Twentieth Century Society (successor of the Thirties Society). Stamp died in 2017, and his manuscript has been seamlessly edited by his widow, Rosemary Hill. Stamp’s distinctive and impassioned voice rings out from beyond the grave. It is a marvellous book; encyclopaedic, full of acidic judgements, and a great celebration of architecture in all its diversity.

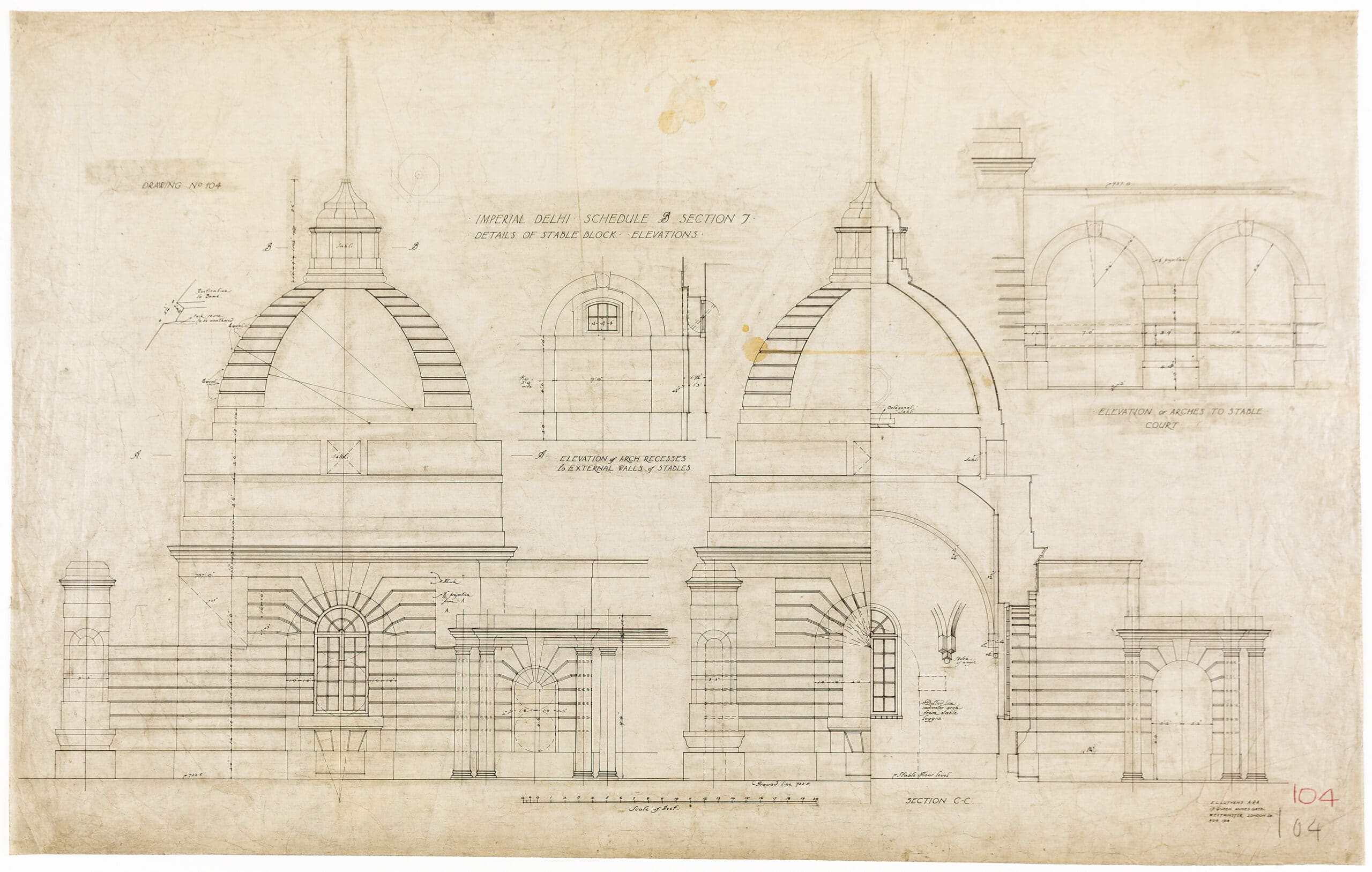

Interwar has had a long gestation and it retains imprints of the polemics of the 1980s. The book is structured around nine chapters covering a full spectrum of styles, which capture the multiplicity of influences on British architecture during this period, with architects frequently mixing a smorgasbord of ingredients from both abroad and the past. It is a surprisingly international history of British architecture from a period often denigrated as inward-looking and provincial, detailing the influence of international trends from Swedish Grace to the American skyscraper. It also follows British architecture abroad, often through imperial networks.

In Stamp’s schema Modernism is implicitly downgraded to one style amongst many—with the flat-roofed house of equal significance to the oft-sneered at Neo-Tudor semi, the Egyptian factory, or the Georgian post office. Although Stamp’s youthful hatred of Modernism was somewhat tempered with age, he deflates any Modernist posturing through a reliance on the satirical gibes of critics such as Evelyn Waugh or Osbert Lancaster. This is all enjoyable invective from a master of the form. Nevertheless, as the chapter on Modernism is titled ‘The Shape of Things to Come’ and concludes the book, one is awkwardly left with the unanswered question of why something so apparently flimsy and eccentric managed to sweep all this diversity away so totally after the Second World War. Elizabeth Darling’s Re-forming Britain: Narratives of Modernity before Reconstruction (2006) provides a better account of why Modernism made such an impact, without returning to Pevsnerian teleology.

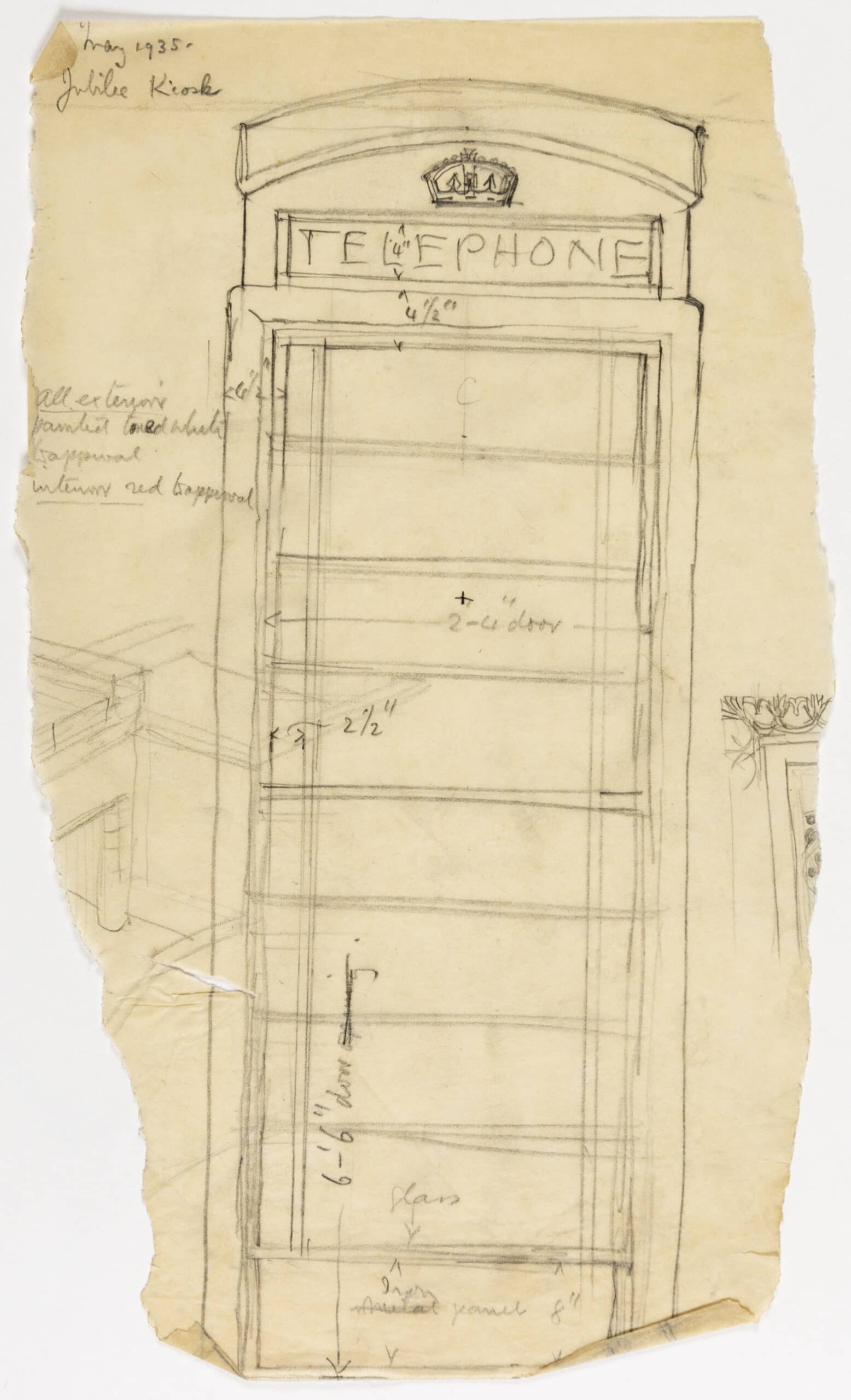

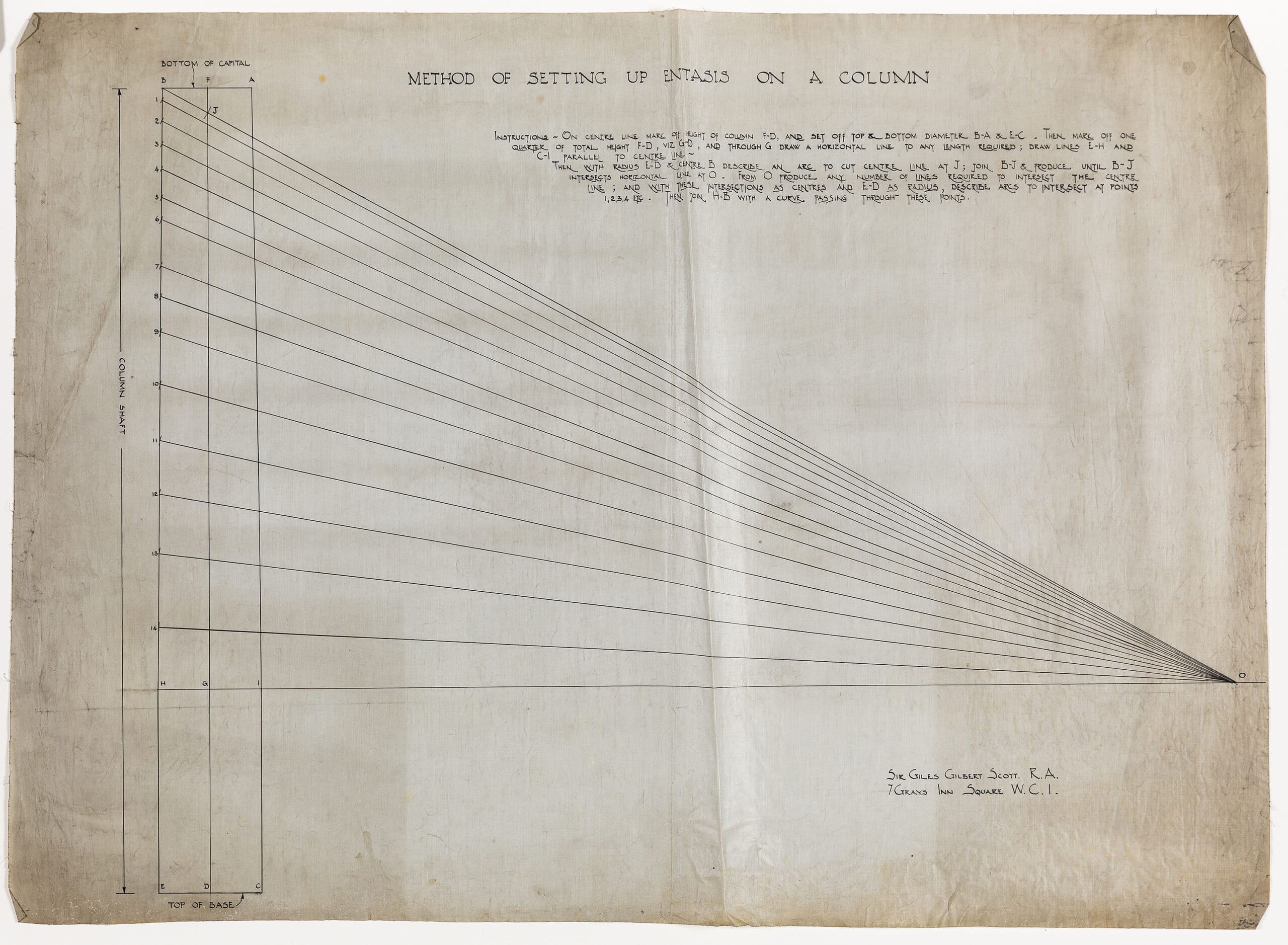

Stamp’s writing is much better when electrified by enthusiasm. Suspicious of purism, Stamp celebrates versatility, and a few heroes emerge. Pre-eminent is Edwin Lutyens, whose extraordinary range and depth as an architect are evidenced by the fact that he reappears at many moments throughout the book. Oliver Hill, Robert Atkinson, H.S. Goodhart Rendel, and Giles Gilbert Scott take their place in Stamp’s pantheon of eclectics. Stamp also elevates from neglect such architects as A.G. Shoosmith, architect of a primal brick church in New Delhi, or Ernest Trobridge, designer of wonderfully bonkers suburban fantasias.

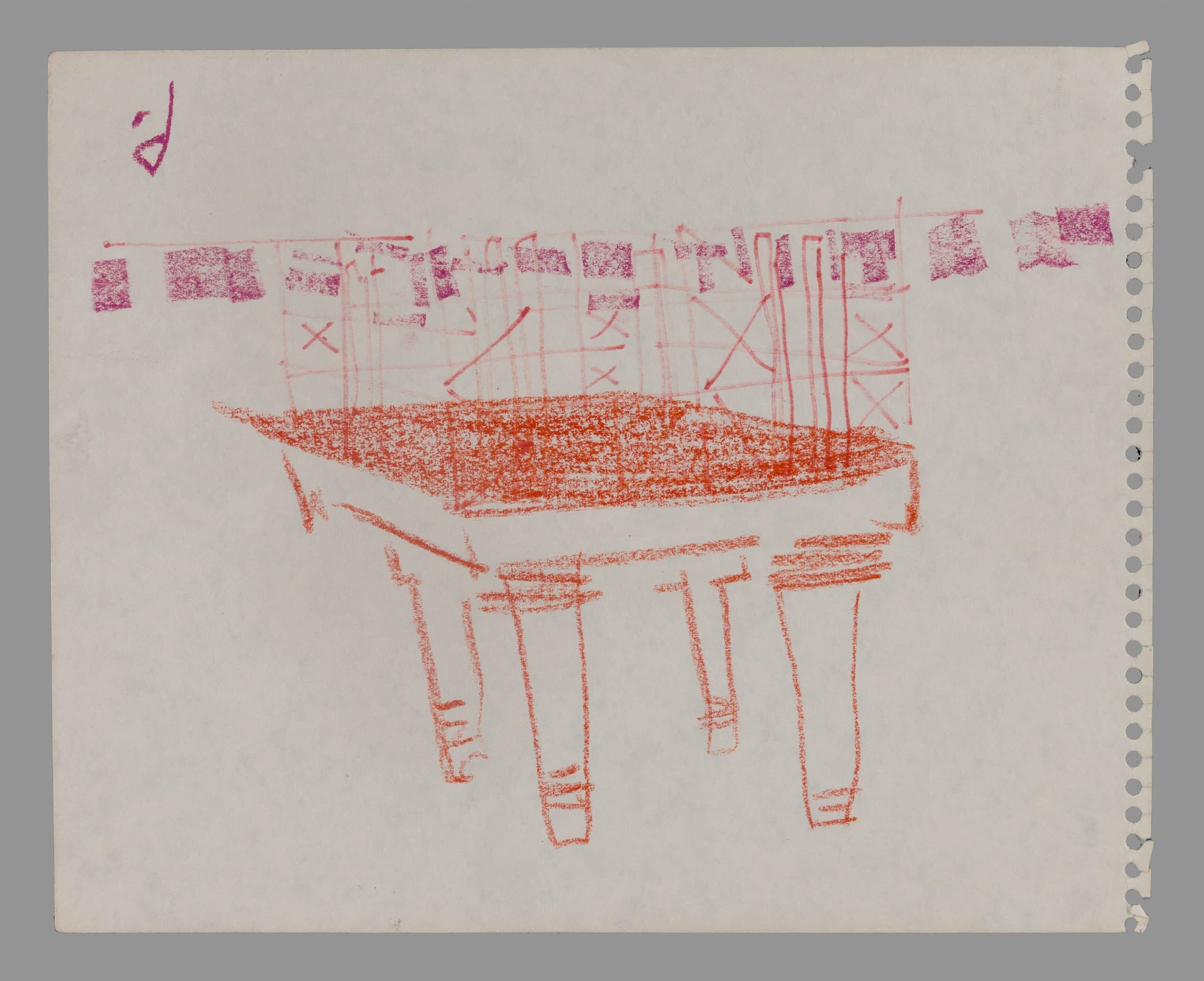

This is though primarily a book about buildings rather than people. The discipline of architectural history has recently tended to be much more comfortable discussing the discourse around buildings, so it is refreshing to read a book so obviously based on direct analytical contact with architecture itself. It includes incisive and illuminating pen portraits of buildings at every scale, from the pub to the power station. One of Stamp’s longest-running conservation battles, for Giles Gilbert Scott’s Battersea Power Station (described by Summerson as ‘Gavin Stamp’s billiard table’), has finally come to fruition with its reuse; but one can guess that Stamp might have had equivocal feelings about the glitzy shopping mall it now contains.

Dr Otto Saumarez Smith teaches architectural history at the University of Warwick. He chairs the Twentieth Century Society casework committee.

Find Gavin Stamp, Interwar British Architecture 1919-1939 (2024) here.

Explore a small selection of drawings from the Drawing Matter Collection, all for interwar civic and domestic projects (including a group of competition entries for ‘Ideal’, and low-cost housing, together with fuller descriptions of the drawings illustrated above).

– Ellis Woodman