Glasgow School of Art: The Measure of Things

The following text was first published in The Library: Glasgow School of Art (2014), edited by Mark Baines, John Barr and Christopher Platt. The text describes Paul Clarke’s process of surveying Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s library at the Glasgow School of Art, which he undertook in 1993. When the library was destroyed by fire in 2014, Clarke’s survey became an unreproducible record of a building lost. His essay, however, is not merely an elegy; it provides a forensic account of Mackintosh’s building and architectural practice, gleaned from closely looking, pencil in hand.

– Drawing Matter Eds.

Voids agape in stonework, where once fine metal grids held shimmering pockets of sky; dark wooden floors misted grey with a moon dust of fallen plaster; once elegant columns scorched into an elephant skin of charcoal and standing like sentinels outwith gravity, shadows of Callinish. At the centre of this landscape of wreckage, the burnt remains of the library are piled high, like a bonfire that has fallen from the sky. Archaeologists pick through the remnants of the library with forensic diligence: collecting, mapping and measuring each piece of burnt fallout into precise, catalogued and boxed collections. Broken books lie scattered and entangled in the briars of twisted steel straps and burnt shards; they are the only recognisable fragments to signal that this scorched shell was once a library. A library and space deeply embedded in the consciousness of a school, of a city, and of architecture itself. A space you stood in, motionless, and mesmerised, by the delicate light and shadows; a world within a world. The library, an unexpected architectural discovery each time you entered. The building itself a rock set in a high place; there to allow us to navigate how we saw the world; a measure against which all other buildings would be measured.

We had taken it for granted. The library, the centring heart of Mackintosh’s masterpiece, mysteriously beautiful and timeless, or so it seemed. But it was lost to us even earlier, before the fire. Its slow abandonment creeping up unnoticed over many years. The role of the library displaced to a more expansive, more efficient space: the banal underbelly of the Bourdon slab. From the height of the west tower in Mackintosh’s building, to an indifferent undercroft on the street, the library had fallen. New forms of encounter with knowledge, with the digital, had brought change. The constantly shifting interface of our information age, stripping spaces of their occupation: from social space to social media, we are free to wander in our digital daze. The dialogue with the book; of sitting at a window in a quiet library; an abandoned pursuit. The doors were generally locked, opening only to the steady rhythm of another building tour come to pay homage to an architectural relic; or for the quiet footsteps of a lone researcher or librarian. The space that had once been at the heart of a great 19th century vision of what art education would bring to society, to industry, to creativity, to knowledge, had lost its place: adrift in the digital age.

In the original 1896 brief, the library had hardly warranted a description. [1] There amidst the long list of rooms conceived to follow a system of drawing and observation required by a Government School of Design, and which was based on the South Kensington System, [2] the library was simply described as:

‘One school library and reading room with a floor space of from 1000 to 1200 sq.ft.’ [3]

Beyond the physical size of the space to be provided, no other request was made in relation to the library. Studio spaces, however, followed a very detailed programme of sequence, storage and light requirements. The paradox: the shortest description in the brief produced the most inventive architectural space in Mackintosh’s imagination. Looking out from within the west tower, across an ever-expanding industrial city, it floated like a vessel within the protective shell of a stone lookout. High above the city horizon, a hidden delicate wooden ship, holding onto its books like the treasured volumes of the exiled Prospero. [4]

Visiting the Art School for the first time after the fire, I walked around in the semi-darkness of a part ruin, disorientated by the destruction. The west tower was embalmed in a temporary protective shroud of scaffolding and canvas. The Glasgow weather was trying hard to billow this veil into life. On the top floor of the west side where the fire had taken hold, the whole attic extension, the hen-run and roofs were gone. The winter light filtered through the protective canvas in a soft glow: a healing halo, holding back the rain. Witnessing room after room of scorched black surfaces, it felt like an earlier Glasgow; of a black soot covered city, populated by buildings that you could run your fingers across like a blackboard. This blackness, now only a memory, but it seemed to me as if the city had been turned inside out, and the industrial dark city that the Art School had witnessed, and been part of, had somehow now seeped back in through the shadows of the fire.

I had been reading a book by Paolo Belardi, Why Architects still draw. [5] It was written as a series of imagined lectures to his architecture students: a plea for the continuing importance and value of hand drawing. His central theme was that the hand drawn sketch was the acorn and essence of the architectural idea. In the midst of our digitally driven world, where the computer drawing and image dominates, he was writing about the space of drawing, and why in particular the hand drawn survey provided a knowledge that went beyond any scientific measure, beyond just physical dimensions. His thoughts shaped a question that had been running through my mind in relation to my own experience of the Art School library: of measuring it many years before; and now witnessing its destruction in the fire. It could be summarised in one of Belardi’s lecture titles. It will be the subtext of this essay:

DOES A FOREST GIVE UP ITS SECRETS IF YOU MEASURE THE HEIGHT OF THE TREES? [6]

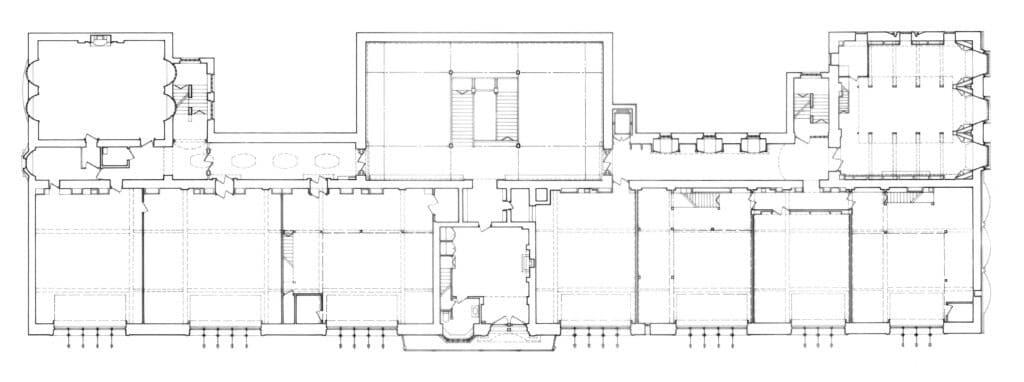

In 1993, while I was teaching at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, I was commissioned with the Historian Dr James Macaulay, and the photographer Mark Fiennes, to produce a book on Mackintosh’s School of Art. It was part of Phaidon’s Architecture in Detail series. [7] The idea was simple: to combine an essay, photographs, and drawings on a modern masterpiece. It had been a successful formula. There was little direction in terms of the drawings. The editor had sent me some photocopies of drawings from an earlier publication in the series, on Aalto’s Villa Mairea with an attached note saying ‘just do them like that’. But how could you approach Mackintosh’s masterpiece in that way? What drawings could do this remarkable building justice and provide new insights? It seemed an intimidating task: to measure and describe a building that you had known and admired from your very first interests in architecture. But what form of drawings would be useful: axonometrics, exploded isometric details, worm’s-eye views, perspective projections?

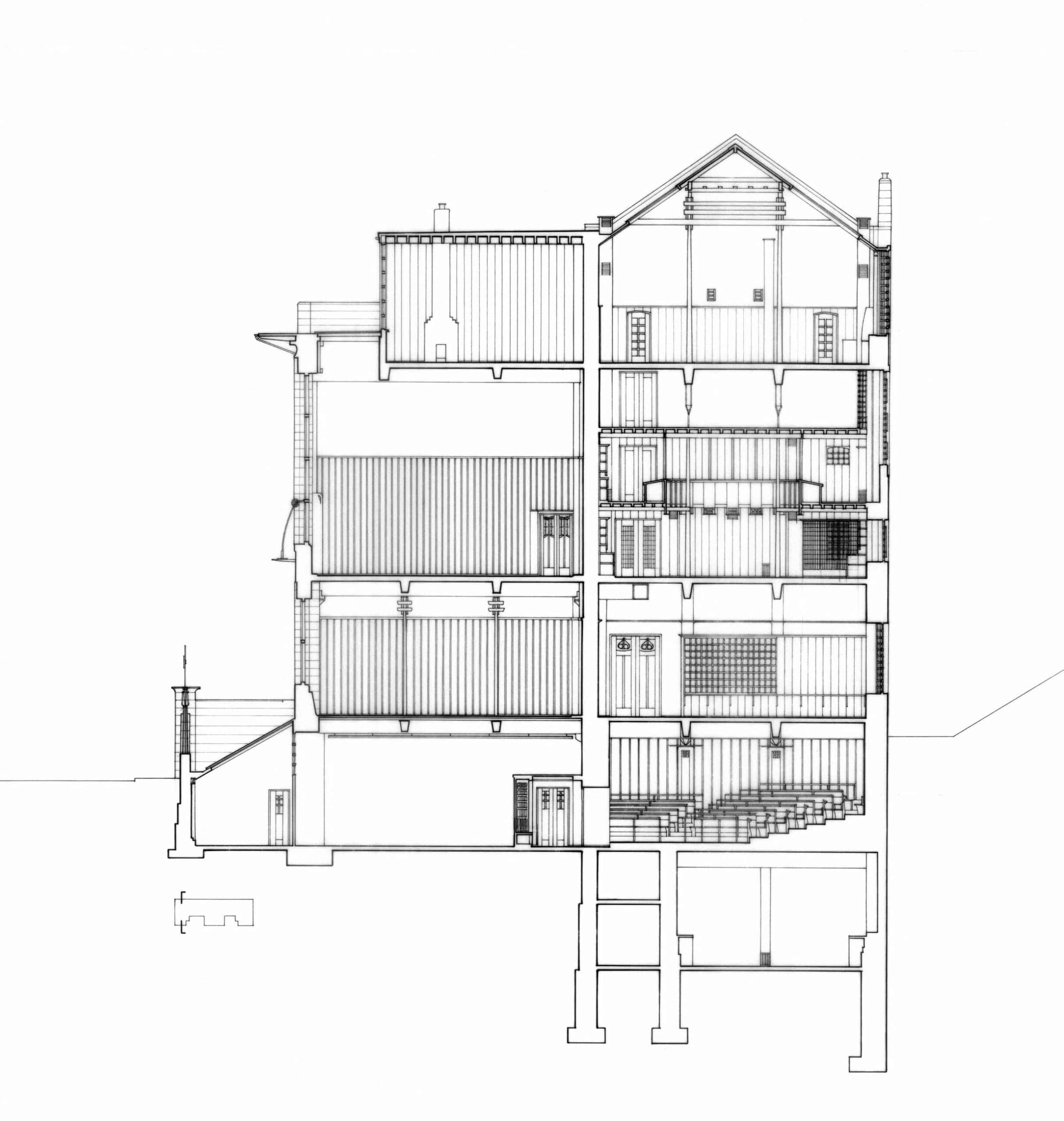

Mackintosh’s creative genius lay in his extraordinary compositional abilities. His approach to whatever he was designing was framed and developed through the use of traditional architectural tools: the plan, the section and the elevation. In looking at the drawings of his buildings, interiors and furniture, the clarity lay in the use of this simple two-dimensional orthographic framework. While his presentational perspectives of buildings are intense in their density and delicacy of line, it is in the traditional orthographic two-dimensional drawing that Mackintosh’s architectural genius is evident: constructive, compositional and symbolic thought. Mackintosh makes his drawing process, which is embedded and absorbed in the traditions of his architectural education and apprenticeship, distinctively his own. In turn he sets the context for his unique approach to detail, and how it is integrated into an overall sense of compositional space. This ‘laying out’ of an idea, through the constructive logic of orthographic projection, sets out the form, measure, material and colour of what is being designed, in a language of drawing that is specifically directed to the making of things, and for exploring the context for the interrelationship between artefacts, furniture, interiors and buildings.

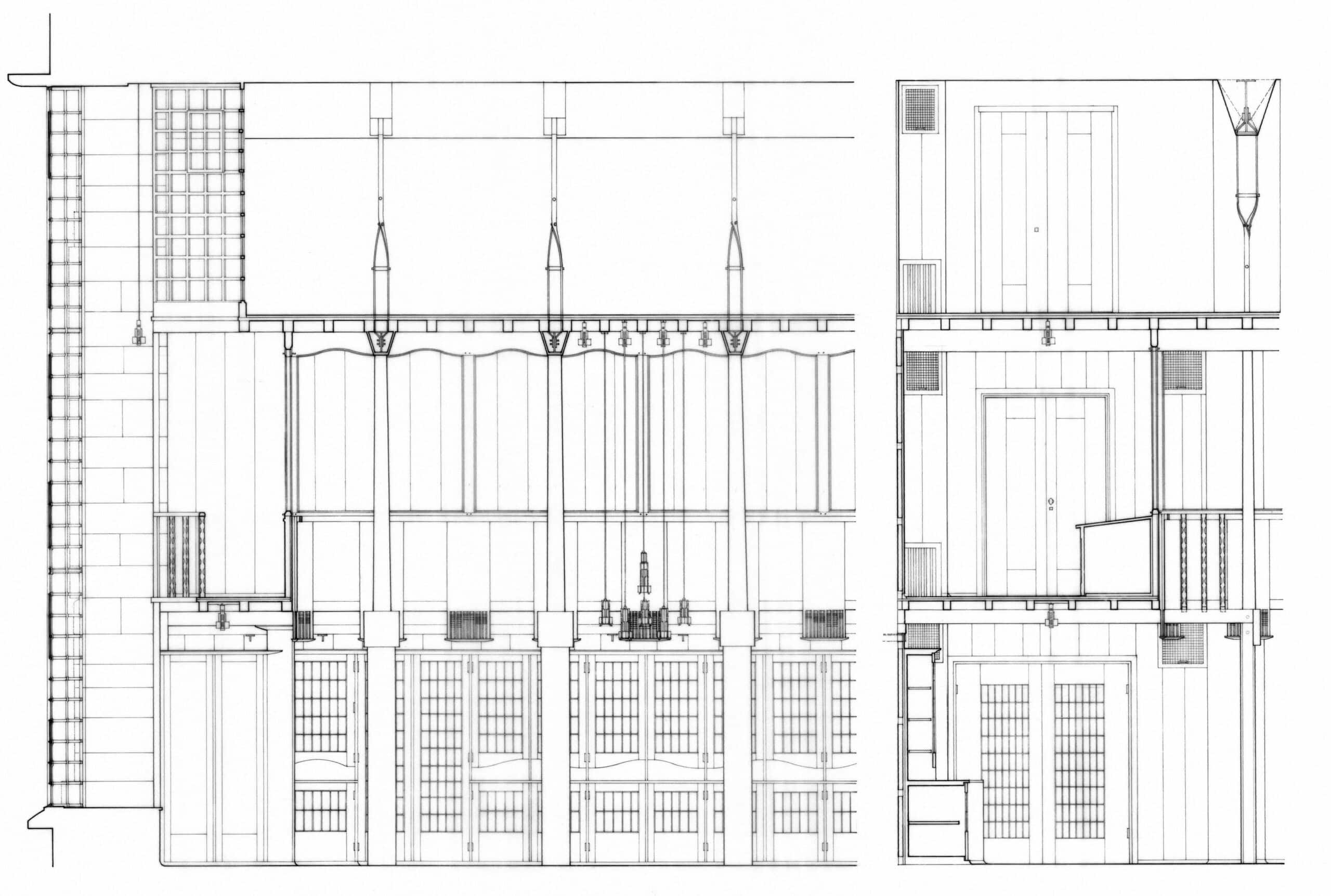

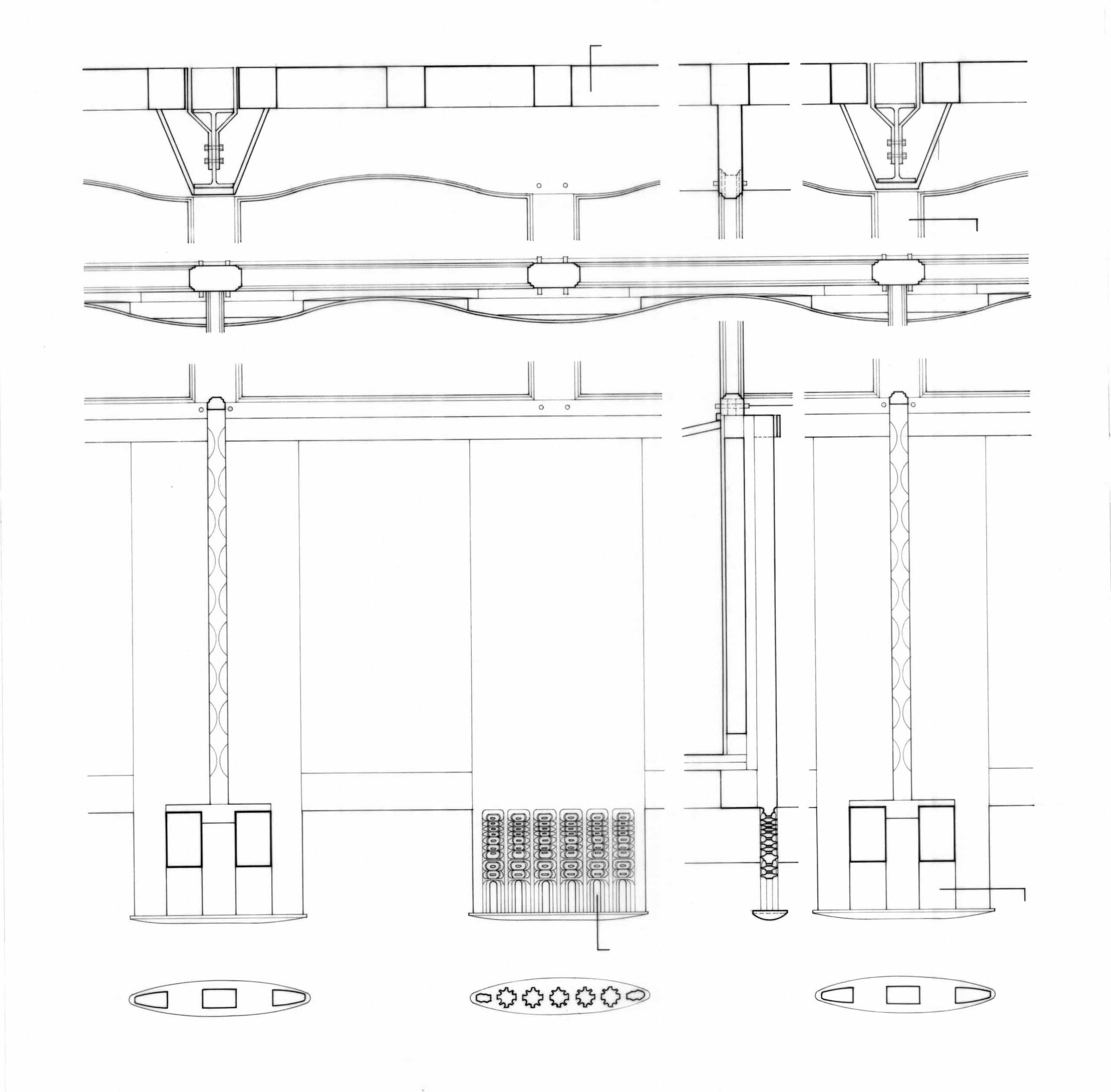

There are very few detail drawings of the School of Art by Mackintosh, other than those of light fittings and furniture. One larger detail section is signed by him, if not drawn by him, but even that is incorrect in relation to the completed details. [8] While overall the constructive fabric in the drawing is materially correct, all the key details that we associate with Mackintosh are shown as standard and undistinguished construction details of the time. This may be due to it being a Dean of Guild submission, for building approval. However, it may, more importantly, reveal Mackintosh’s process for transforming the ‘standard’ details of the day. But how were such unique detail ideas instructed? Were the drawings handed directly to the craftsmen and then destroyed or discarded once the works were complete? Was this a standard approach in building at the time, or a strategy to allow the compositional detail to be developed and emerge relatively ‘unseen’ amidst the intensity of the daily site construction work? In contrast to our contemporary obsession with vast arrays of drawings, contracts, schedules, multilayered BIM three-dimensional models, and specifications – where everything is fixed and prescribed in advance – the clarity of the general layout drawings and sections produced by Mackintosh set out a framework for the inventiveness of his detail to flourish. This allowed, within the direct organisational logic of the Victorian plan, a series of territories within the building to emerge for the detail explorations and ideas to take shape. But this approach required time, experience and the knowledge of what was possible with the materials, and the abilities of the craftsmen available. For Mackintosh this took shape in ordinary things: staircases, doors, clocks, railings, cloakrooms, and roof trusses. Or in a simple library space, defined only by a set floor area. Seemingly mundane or ordinary parts of the building were thereby given shape by the combination of the restlessly inventive mind of the architect, in tune with that of the hand and craft of the makers and fabricators. If the pencil line gave form to Mackintosh’s thought, so the hand of the craftsman left its trace on the material. Few would see or know what detail would emerge until it was complete. The craftsman, ready to work on a seemingly straightforward detail, would be handed a drawing, to work directly from. This was a strategy for which the building committee took some time to recognise, and to which they eventually reacted (unfortunately). [9]

Mackintosh knew of Ruskin’s belief – as described in The Stones of Venice – that a building could be considered a ‘document’, composed of the individual ‘signatures’ of the craftsmen, set in the materials. [10] If these ‘signatures’ were to take shape in the ordinary elements of the building, then Mackintosh would be the one firmly holding the pencil to ‘write them’. Mackintosh did not subscribe to the approach of many of his contemporaries, who would often leave much of the detail resolution to the craftsmen, to conceive or to deploy from a standard repertoire of Victorian ornament and classical profiles. Instead, Mackintosh continually invented new forms and compositions in each of the materials and elements he worked with, no matter how seemingly mundane their function. Mackintosh repeatedly turned to the world of the things ‘seen’ and ‘collected’ in his sketchbooks to inform his composition. From the careful observational drawings of seasonal flowers, to the shape and mechanism of a door latch on a vernacular barn, this inventory of memory would forge the context in which the material ‘signatures’ of his buildings and furniture would evolve. Contrasts, shifts and discontinuities were embraced and apparent as part of this process of looking and making, and in shaping the Glasgow School of Art as a Ruskinian ‘document’. In itself this ‘document’ can be read to measure the changing ideas and compositional skills of the architect, gained over an extended period of time during the two phases of the building, and as a witness to his changing approach to such materials as: stone, brick, timber, glass, cast iron and steel – the well understood palate of materials used in the labour intensive Victorian building industry.

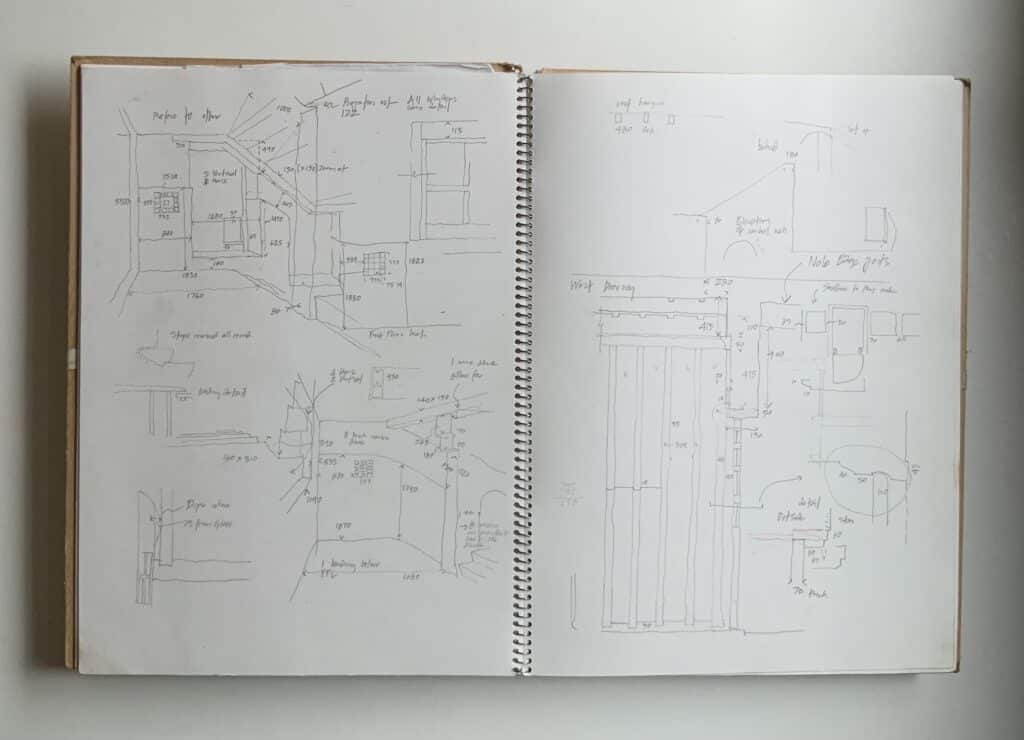

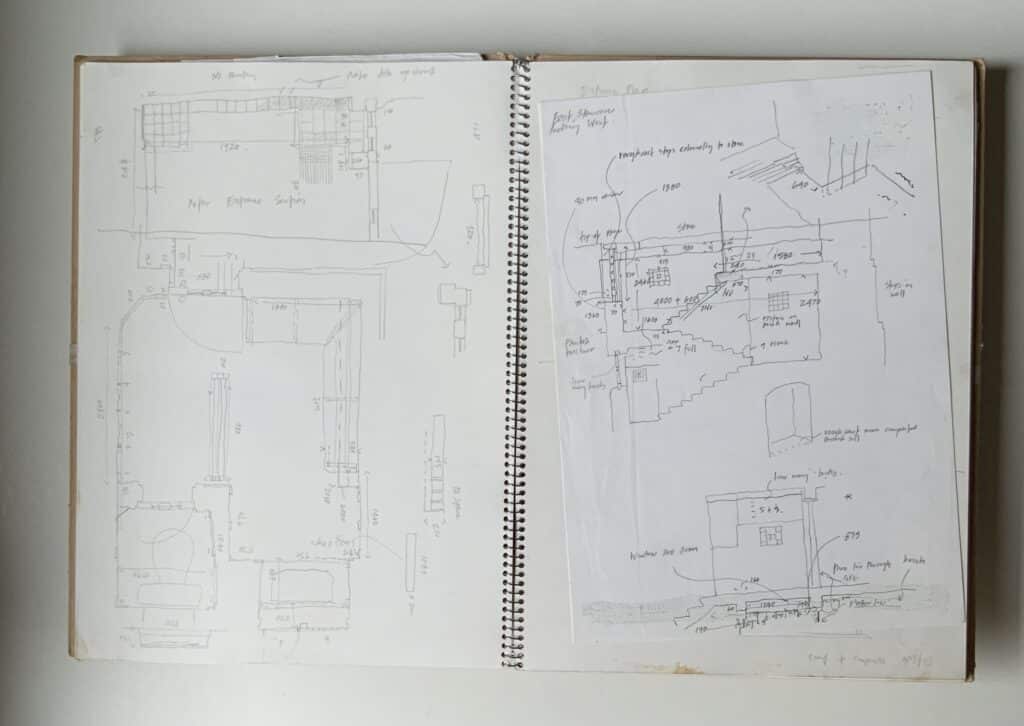

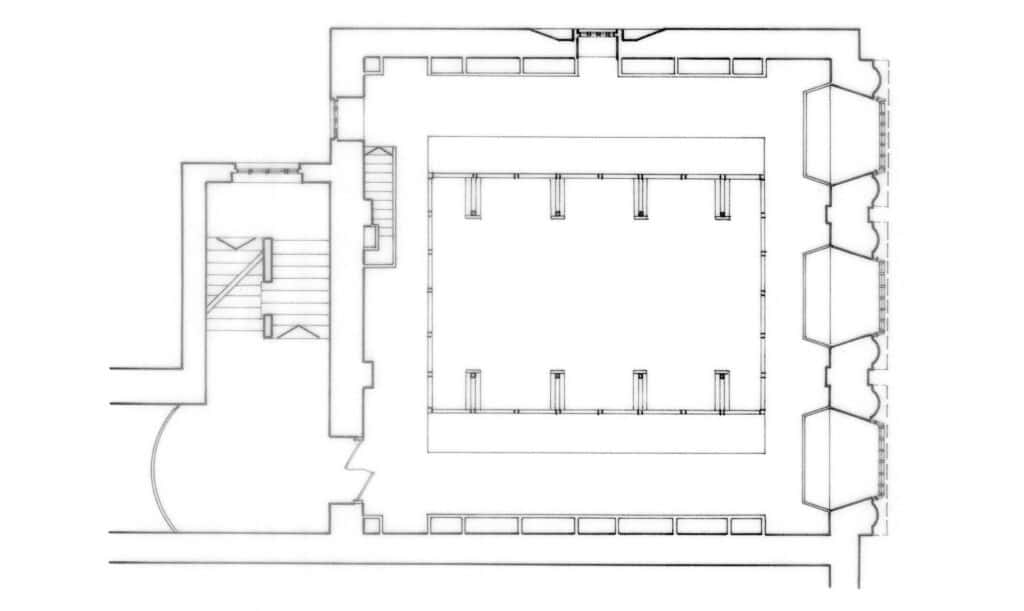

To explore the significance of the detail in the building then, the ‘signatures’ needed to be viewed in the wider context of the architectural sequences, elements and spaces. In order to do that, I decided to focus on specific ‘landscapes’, within the building. These ‘Landscapes’ are the overall architectural events, forms, proportions, and spaces that when considered together, produced something unique, and which were in scale terms, between that of the overall building section, and the smaller individual details. A simple cartography of these ‘landscapes’ would be how I would approach the drawings. Two staircases added in the final phase, like outcrops to be scaled; several remarkable doors and doorways, such as the west doorway with its sequences of convex and concave movements in the stonework; the hanging system of the upper studio walls; were all key to this cartography. But it was the library that revealed the most challenging ‘landscape’ in the beauty and rhythm of its detail, construction and space.

I decided to adopt the simplicity of the two dimensional orthographic drawing process, through which these ‘landscapes’ had been conceived. If music comes alive in the experience of how it is performed in time, in the interpretation of the written score, then so too does architecture in the experience of its constructed material space, in time. You must return to the notational framework, or score, to find the origins of the compositional idea. Like that of the building overall, the library is conceived from within the logic of its own structure, not just in the physical fabric of the structure, but more importantly within the notational structure of how it was drawn: a composition within a composition; of layers within layers. It would have to be set out, as it was thought out; measured as it was measured; but now in reverse; to start with the music in order to find the score.

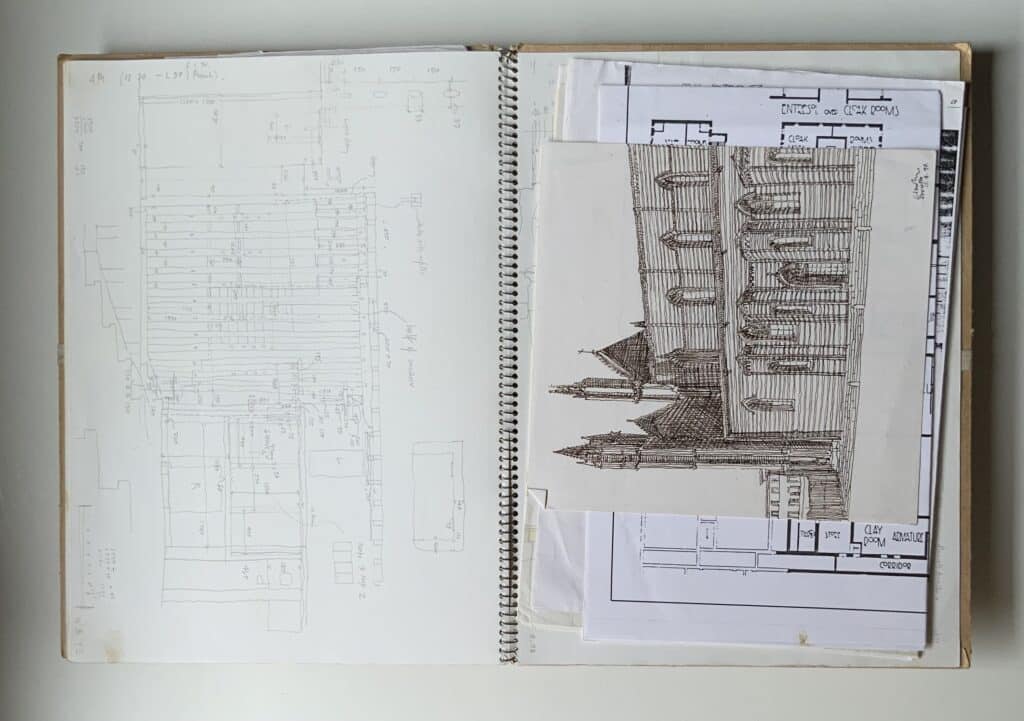

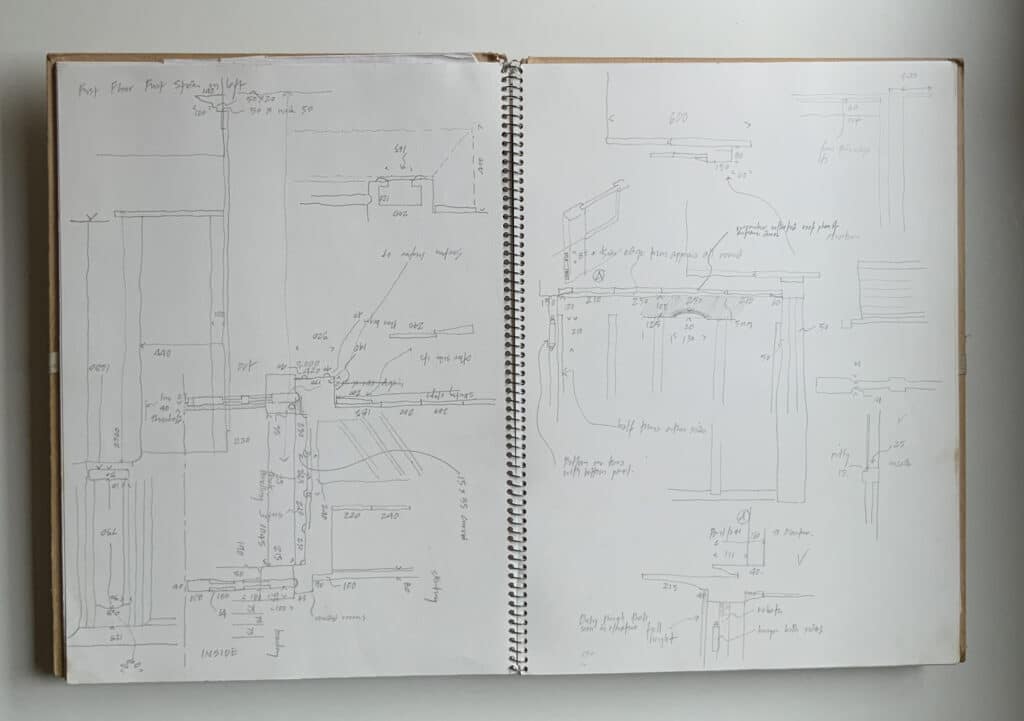

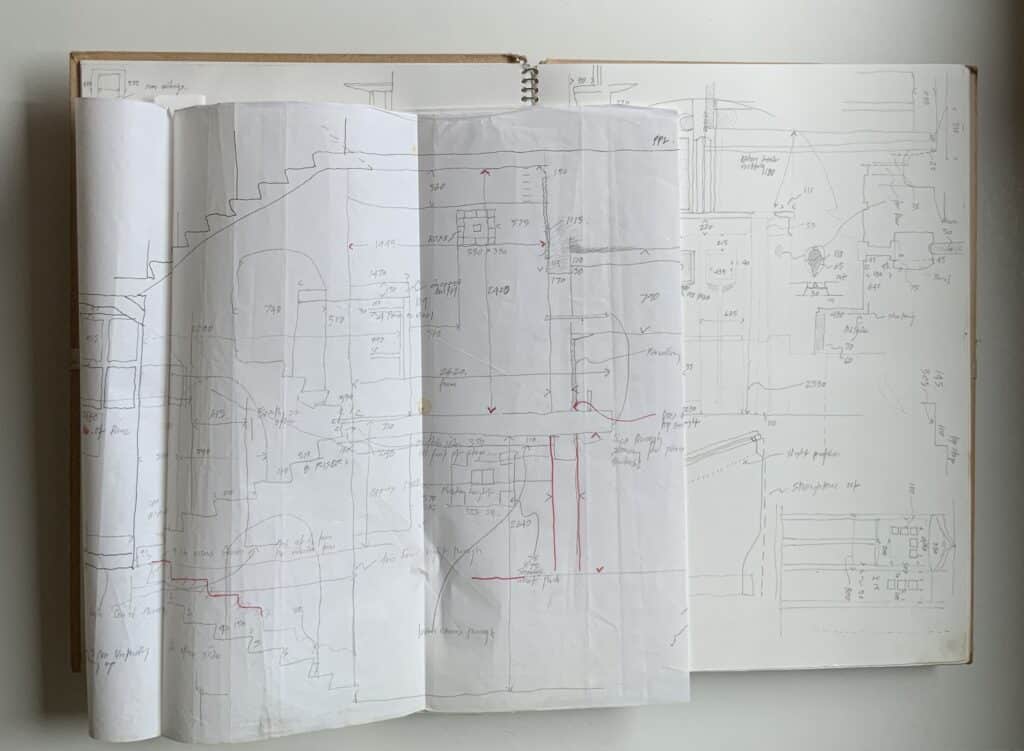

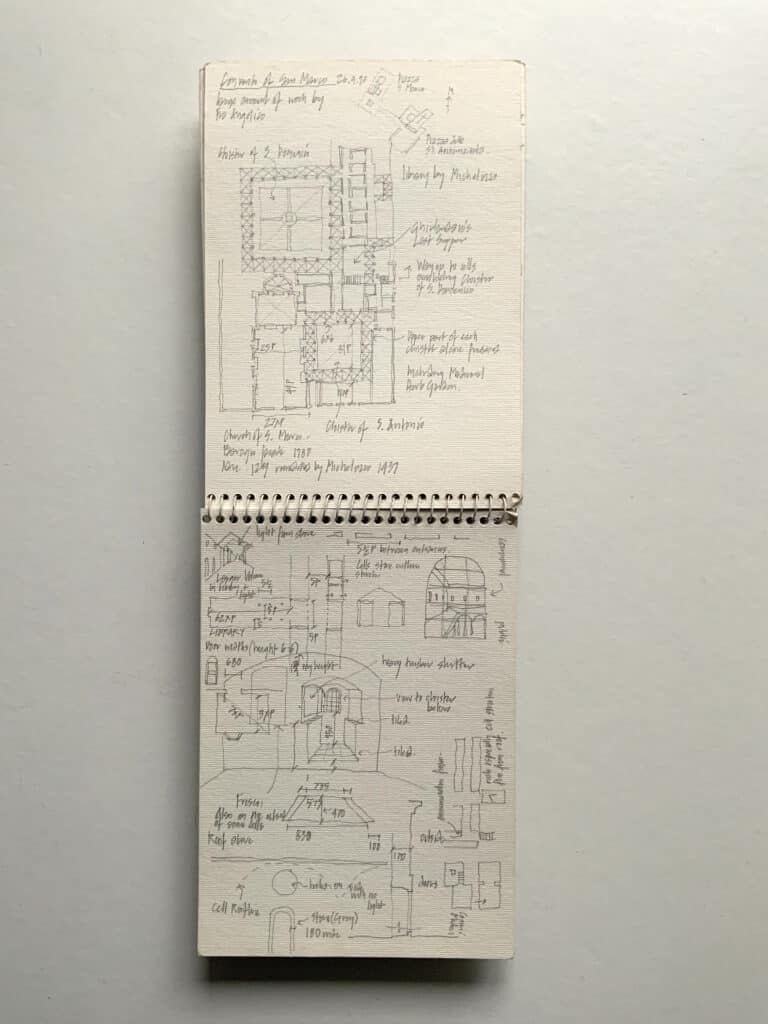

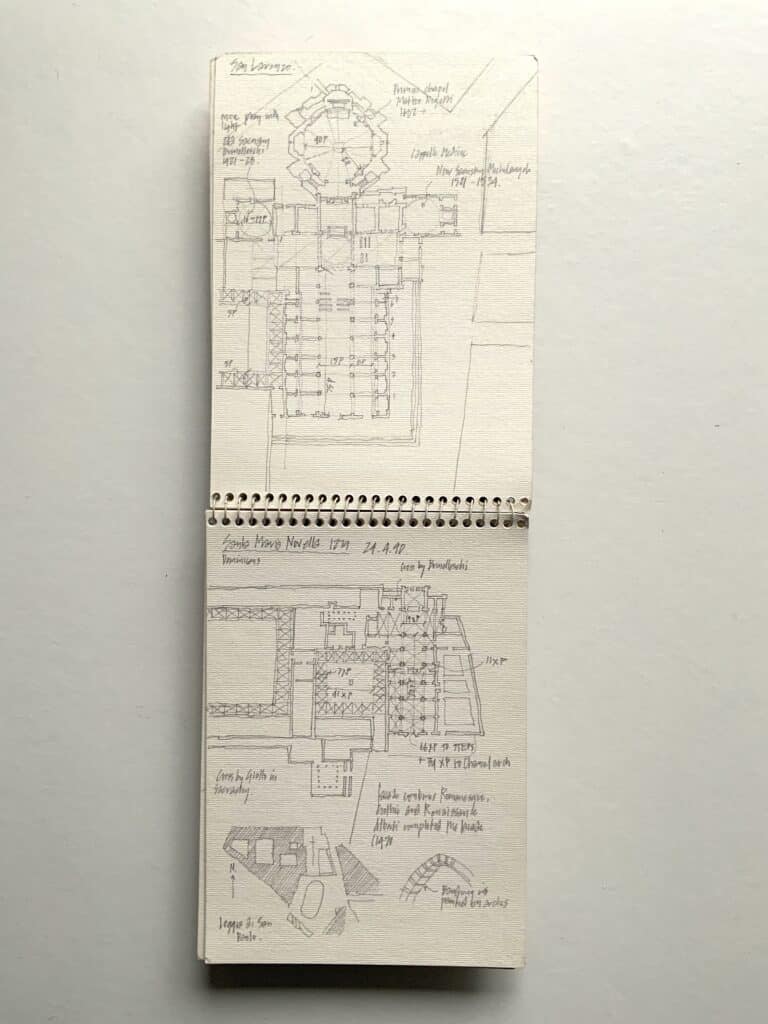

I decided against taking photographs. Everything I would discover would be through drawing and measuring, placed in one notebook (bought from the art school shop). I began a daily dialogue with the building: drawing, measuring, re-measuring, and re-drawing, made possible by working in close proximity. Every spare moment between teaching, early mornings, lunchtimes, days off, was spent in the building. Without a camera there was an opportunity to really look; and through drawing to see; and then maybe to understand. This was a tradition as old as architecture itself; of the importance of ‘slowness’: of looking, of drawing, of measuring, of looking again, of thinking, of drawing and again. The experience was an intimate one: from the eye to the hand, from the hand to the drawing, from the material to a measure; tracing out overlooked lines, finding the different contours of materials, imagining hidden joints, all the time using the hand to guide, to measure, to draw and to touch.

The survey notebook, like that of the anthropologist’s fieldbook, becomes the holder and collector: awaiting translation. As I measured the library, it slowly revealed its dimensions, its details; things I had not seen before. At times I was surprised by the bluntness of the detail; watching the idea and the material playing out; discovering combinations of forms; tensions and material shifts; moments of potential conflict in the artifice; geometry and craft resolved in the register of its own logic, and invention.

As Belardi’s book suggests, nothing could, or would, decode the library through measure. A drawing could only ever act as an evocation towards the original creative idea, which fully comes alive in the phenomenological experience of the constructed space. If some composers feel that the power of music is set by the unique nature of the interpretation of it from the score, then accordingly architectural space is experienced as a series of individual ‘readings’ of an original architectural idea.

The idea of the library had been germinating in Mackintosh’s mind for a long time. Between the two construction phases of the building, it had gone from an indifferent and predictable layout – as described in the early competition drawings – to one of the most distinctive spaces in 20th Century architecture. In the first phase of the building the library was temporarily set up to one side of the museum space, as a set of cabinets against the wall. This remained the location until the completion of the second phase, when the library moved to the west tower. Between these two phases of the building Mackintosh’s world had changed. What he had seen and experienced through travel; the changes in his private and professional relationships; what he had learned and developed through building; what he had drawn and imagined in his sketchbooks and foretold in the vibrant watercolour washes of his symbolic drawings; would all come to influence his work and his approach to the second phase of the building.

If the anatomist’s knife has historically probed the layers and dimensions of the human body, in order to gain knowledge, then there is something of a dilemma in this opening up, and separating the world into, the seen and unseen. The skin of forms, of material constructions, of the rhythms and movement of space, can all be shorn of life in the scientific inquiry for knowledge, and measure. If music grows from silence to form, the architect’s measured survey works by taking things apart through number, line and drawing: to uncover and dissect the phenomenological pact, of how we experience space and materials. If in his famous book of anatomical drawings Vesalius sets free his half dissected cadavers to wander across strange Beckett like landscapes, and to stand upright at the very tables they would normally be lying on, cut open, then he does so to defy our perceptions. [11] Knowledge is not absolute, nor is it to be restricted from playing out in our imagination. It does not follow that any scientific inquiry will provide the answers; as to how and why we are moved by what we see, and feel. Our constant need to know, to catalogue, to categorise, and to measure, is but only a worthy absurdity, in holding back an ever repeating Sisyphus condition: our endless search for knowledge and meaning. We look out over a complex world that is ever changing, incomplete, fragmentary, discontinuous, and wonder at it. To know it, you must continually re-make it. Mackintosh’s art centred on this re-making of the world: of transforming the ordinary things that surround us into sublime windows to look back into the world, to enrich our experience of it, and to see the possibilities of Art in re-making it.

When I completed the survey of the library; after I had spent days measuring it, walking it, studying the details, as I had other parts of the building; had I come any closer to knowing it? Did I have a different insight beyond the first day I had walked into the library and felt its hypnotic beauty? Did my ‘laboratory’ notebook of measurements, notes and drawings offer any code-breaking information into Mackintosh’s genius? I had discovered many things: about the building; about the library; about myself; about the people who worked and studied in the building; about discovering books in the library; about how to find keys to open long closed cupboards; about looking out over the city through the small grids of the windows; and about the shifting, changing light of a day, across the dark wood of the library.

When all the drawings were complete, and the book was published, the notebook was closed. It was closed for over twenty years. On the day I heard about the fire, and that the library was totally destroyed, I opened it again for the first time. Measure for measure it came back; like a score in my head; but knowing now, that it all, only existed in silence.

We know that Mackintosh conceived the library to be in oak, and in order to make savings, as the financial control and the completion of the building began to be taken away from him, it was changed to the cheaper material of pine. [12] But did the dark stain of the completed library mask the dream of another material? Is this thought of oak echoed in its detail? Did the abandonment of a material, so loved in all of Mackintosh’s furniture and interiors, cast a shadow over his ideas for the library, or did it transform it?

If oak had been approved, what then? We can never know. Mackintosh could transform materials and make them feel as if they had come alive with his invention, while at other times the material is deliberately insignificant to the power of the idea. Oak could easily become hidden, under layers of white paint. But was the mystical force of the oak hidden in the rising and falling of the coloured chamfered notches in the library balustrades; leaves calling from each season, with their carefully selected colours and rhythms? Was the oak’s transformative power set in the richly carved pendants, seeded with stacks of time; each one unique like a tree? Can it be found in the undulating rhythms of the concave and convex panelling and pendants; or in the rippling band that traced the push and pull of the panels, throwing the plan into movement, and a sense of oscillating time? Is there a sense that there was more; of something stopped in time?

Thomas Howarth captured the mood of the library beautifully in his description of it as:

‘…the silent, brooding pinewoods of the Trossachs.’ [13]

But the pine and the oak stand in the same forest. When an aspiration to make something in a specific material is lost, is this memory held in time?

With the fire there is time again; time to remember what has been lost; time to imagine what could be. When the forest that we so loved has gone, the only thing possible is to plant it again; to wait; to watch it grow; to discover the qualities of the new trees; and to know that their secrets will not be given up in measuring them.

‘When the oak is felled, the whole forest echoes with its fall, but a hundred acorns are sown in the silence of an unnoticed breeze.’ [14]

Notes

- The brief for The Glasgow School of Art: Conditions of the Competition of Architects for the proposed School of Art. First published in Appendix A in: William Buchanan, Mackintosh’s Masterwork: The Glasgow School of Art (Glasgow: Richard Drew Publishing, 1989), 205–212. It is now available online in the catalogue of Mackintosh Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning. The www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk brief is dated as June 1896.

- The South Kensington system was based on The National Course of Instruction which required some 23 stages of drawing to be followed. The brief for the Glasgow School of Art was based on this system of instruction.

- The library is item 9D in the schedule of accommodation in the 1896 brief.

- In Shakespeare’s The Tempest Prospero (the rightful Duke of Milan) is put to sea with his daughter Miranda. Exiled on an island he turns to the few possession he has brought: his books, in order to rebuild the world he has been exiled from. This is played out to great effect by Peter Greenaway in his cinematic exploration of the Shakespeare play: Prospero’s Books (1991).

- Paolo Belardi, Why Architects Still Draw: Two Lectures on Architectural Drawing, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2014)

- This subheading appears in the second of the lectures: ‘No Day Without a Line: A Lecture on Informed Drawing’ (Belardi, 95–109).

- James Macauley, Architecture in Detail: The Glasgow School of Art,(London: Phaidon, 1993). This book has gone through a series of reprints in different formats. Many buildings were covered in this original series including two on Mackintosh with drawings by the author.

- This drawing can be viewed online as part of the catalogue of Mackintosh Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning. The original source is identified as Glasgow Dean of Guild. This online catalogue provides an excellent resource to Mackintosh’s drawings in relation to not only the Glasgow School of Art, but all of his other buildings and projects.

- It is well documented that during the second phase of the building Mackintosh’s proposals for materials and designs came increasingly under the scrutiny of the building committee. This was specifically in relation to the cost of works that Mackintosh had instructed and which differed from that which was approved by the committee or which appeared on the drawings. The famous painting by Francis Newbury of the building committee to which the painter added Mackintosh at a later stage to the canvas, shows Mackintosh’s estrangement from the committee.

- John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, Volumes I–III (London: Smith, Elder & Co, From 1851–1853)

- Andreas Vesalius, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Volumes I–VII (1543)

- We know from the records of the building committee that this was the case and that Mackintosh was forced to make various savings such as the type of wood to be used in the library in relation to the overall building costs.

- Thomas Howarth, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement (London, Boston and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952. Reprinted 1977). This quote is from page 89 with reference to the Library in the section on the Glasgow School of Art.

- Thomas Carlyle, ‘Historical Essays’ in The Norman and Charlotte Strouse Edition of the Writings of Thomas Carlyle (University of California Press, 2002). This quote is taken from the essay called ‘On History’.