Goldfinger—Planning Your Neighbourhood

At first glance Planning Your Neighbourhood appears as a series of prints in a case, and its use is unclear. This series of twenty prints was created by modernist architect Ernö Goldfinger, artist Ursula Blackwell, illustrator Shiela Hawkins, landscape architect Peter Shepheard and their assistant Martin Cobbett. Rather than solely a series of prints, Planning Your Neighbourhood was a touring exhibition produced in 1945. It reflects Goldfinger’s holistic approach to architecture, working across the scale of the object to the neighbourhood, and drew from his expertise in designing for children. It represents a significant aspect of his architectural output during and immediately following the Second World War.

From 1941 onward planning began to occupy the British imagination, as architects forecasted the nation’s future and promoted their ideas to British citizens by positioning them as a future worth fighting for. This process of planning extended from the dwelling to its place within the region as architects anticipated the post-war world. Because the Blitz had wiped out entire areas of major British cities, many architects saw the war as a chance to enact comprehensive town plans. To get ordinary citizens on their side, they publicised planning concepts in popular periodicals, such as Picture Post and Ideal Home, and created exhibitions.

During this time Goldfinger, too, turned to developing proposals, writing articles and creating exhibitions. From 1943 to 1947, he researched and created a series of nine displays for Britain’s Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA)—an organisation that sought to educate members of the armed services in areas of current events and prepare them for the demands of the post-war world. Set up in 1941 as part of the Army Education Scheme with the goal of boosting morale in the Army, Air Ministry and Admiralty, ABCA contended that informed citizens would make better soldiers. Exhibitions supported ABCA’s mission of educating British service members about aspects of British life and culture. Each display comprised a series of screens that were installed in a sequence in ad-hoc exhibition spaces such as mess halls. Goldfinger’s exhibitions for ABCA included the wartime Cinema (1943), Food (1943), The County of London Plan (1944), Traffic (1944), Health Centres (1944) and Planning Your Kitchen (1945) as well as the post-war Planning Your Neighbourhood (1945), Planning Your Homes (1946) and The National Health Service (1947).

Goldfinger produced many of these displays, including Planning Your Neighbourhood, in collaboration with his wife, artist Ursula Blackwell. Because the Hungarian-born Goldfinger remained a Polish national throughout the war, he ensured that his foreign name appeared alongside an English name whenever possible. Blackwell was herself a trained artist, so she almost certainly had the experience in exhibition making that would enable her to adopt an active role in creating the ABCA exhibits. As with any collaboration, however, it is difficult to determine the extent to which Blackwell contributed to these projects. To create each display, Goldfinger and Blackwell combined photographs, drawings, diagrams and maps with informative text captions. They designed each set of panels to be small in scale so they could be transported easily to remote locations on motorbikes.

Presented as a series of twenty boards that measured about 508 x 356 mm, Planning Your Neighbourhood highlighted people and their behaviours in order to demonstrate that the actions of everyday living should shape new dwellings and their surroundings. Exhibitiongoers met panels that depicted how planned neighbourhoods would integrate housing, schools, shops, employment, recreation and transportation to enable visitors to be active British citizens. In total more than one thousand copies of Planning Your Neighbourhood circulated throughout the country from late 1945 onward.

Planning Your Neighbourhood reflected reconstruction policy that had been outlined in key government-sponsored documents such as the Beveridge Report (1942) and the County of London Plan (1943). In December 1942 economist William Beveridge published his report on Social Insurance and Allied Services, commonly known as the Beveridge Report. This document identified five ‘giant evils’ standing in the way of social security: want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness. ‘Squalor’ meant that many British people lived in small, poorly equipped houses that lacked proximity to fresh air and green space, were often located far from their residents’ workplaces and were difficult to keep clean.[1] Remedying ‘squalor’ meant creating a planned urban fabric that provided green space; easy transportation to employment; and modern, easy-to-clean and well-ventilated dwellings. Charles Latham, leader of the London County Council, referenced the report in his foreword to the County of London Plan (1943), where he outlined the herculean task of reconstructing the capital.[2]

Two of Goldfinger and Blackwell’s 1944 ABCA displays, Traffic and The County of London Plan (an exhibition based on the document of the same name), began building upon these ideas by revealing how town-planning professionals would improve London for its users. The following year, Planning Your Neighbourhood presented a more fully realised and clearly articulated vision that embraced modernist graphic design. Each screen presented one main image that often occupied the entire board. Goldfinger and Blackwell predominantly employed text in the form of brief headings and captions, rather than the dense explanatory texts that they had used in their previous ABCA displays. They instead used modern typefaces, plans, Isotype and colour-coded illustrations to create a clear narrative. This shift in approach may have occurred after Goldfinger saw the travelling exhibition Look at Your Neighborhood, which had been curated by Swiss architect Rudolf Mock for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was shown in London at the Housing Centre in September 1944 before touring the country. While there is no evidence that Goldfinger saw the exhibition’s London showing in person, its screens appeared in Architects’ Journal in 1944 and Goldfinger’s archive contains photographs of each panel.[3]

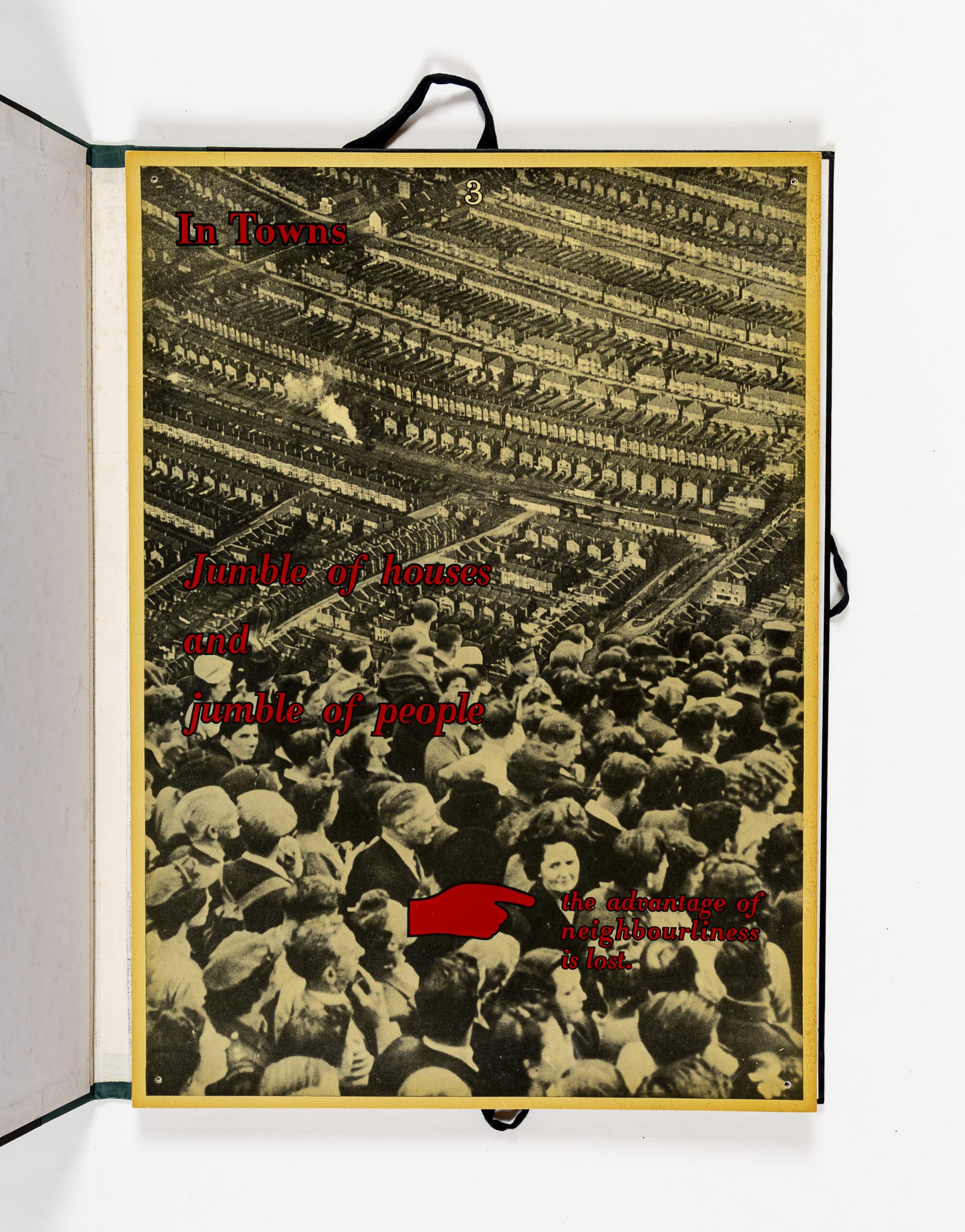

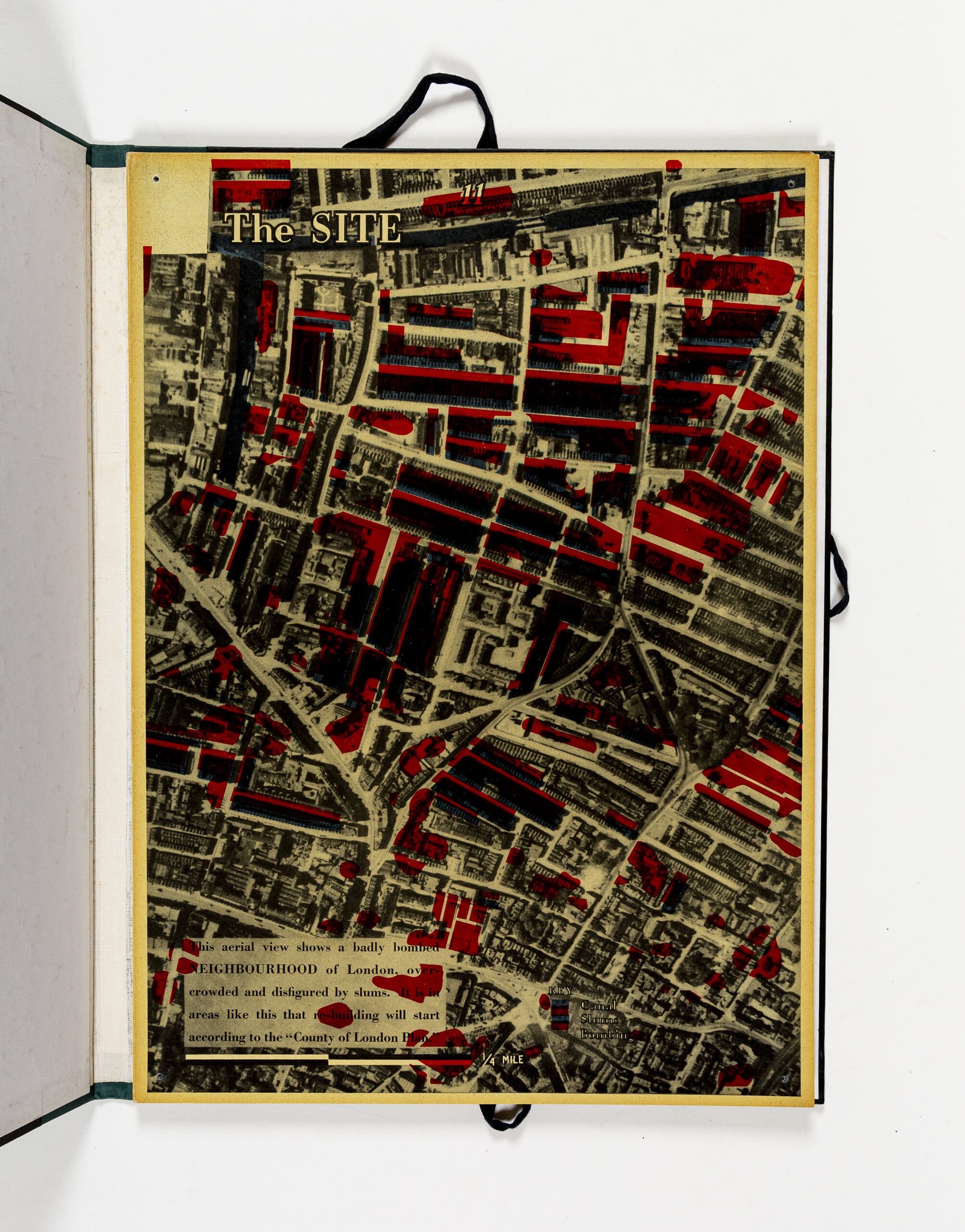

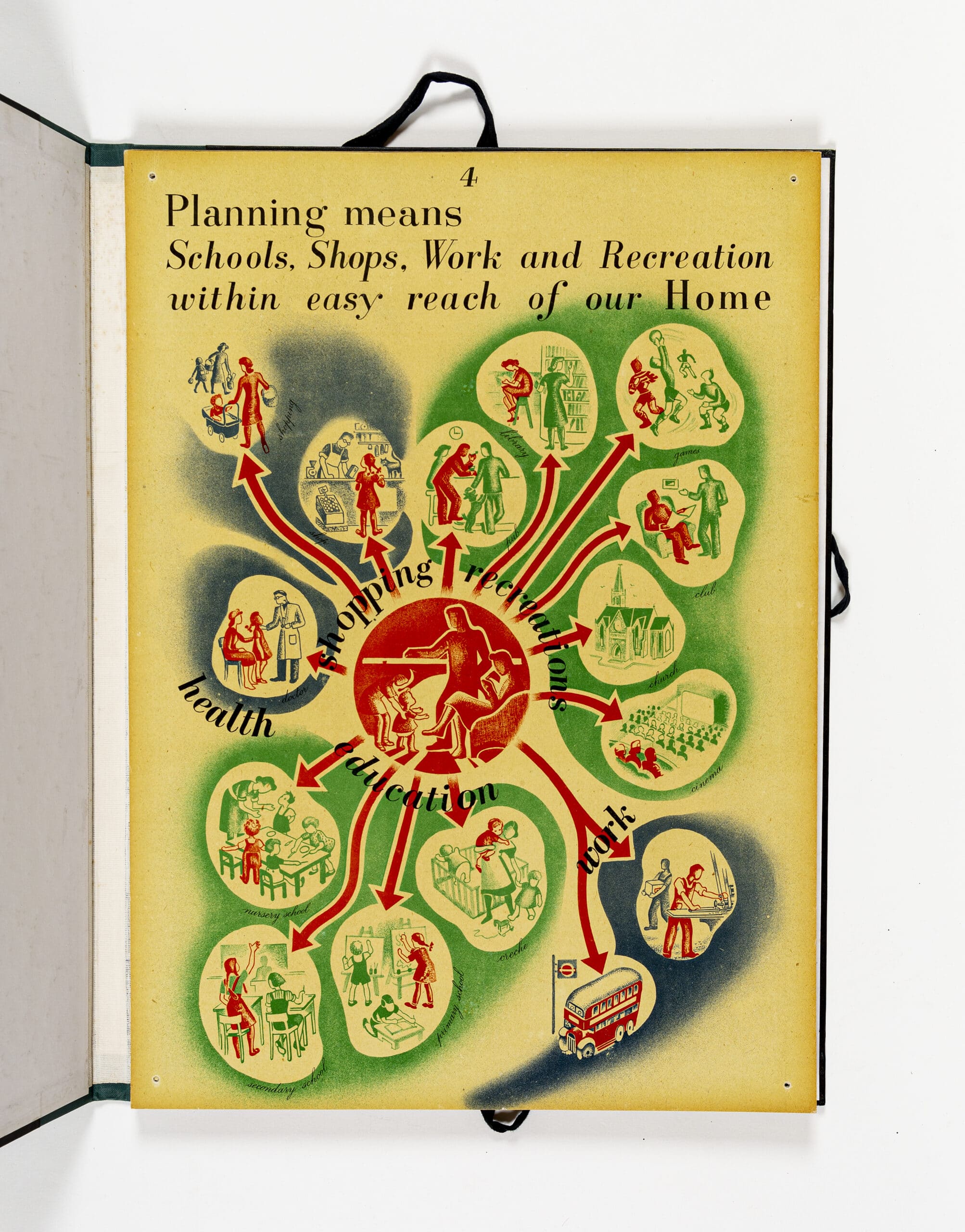

Planning Your Neighbourhood was produced in collaboration with illustrator Shiela Hawkins, landscape architect Peter Shepheard and Martin Cobbett. Notably, Shepheard had worked with town planner Patrick Abercrombie on the Greater London Plan (1944), which aimed to amend and extend the proposals and solutions that were outlined in the earlier County of London Plan. A title panel opened Planning Your Neighbourhood by showcasing three illustrations that depicted members of a family interacting at home, at work and at play.[Panel 1] Boards two and three idealised rural life to suggest that British villages had historically facilitated neighbourliness, while the advantages of community had been lost in large industrial towns. Panels four through eight focussed on the activities of family members—learning, shopping, working and playing—to demonstrate that planning would provide better lives for British people by ensuring that schools, shops, work and recreation would be within easy reach of their homes. These homes formed the focus of panels nine and ten, which insisted that dwellings should come in different forms depending on the size of a family and the needs of a community. The rest of the display—panels eleven through twenty—focussed on the reconstruction of Shoreditch, one of the heavily bombed parts of East London that had appeared in the County of London Plan, to illustrate how planning would benefit one specific community. Because none of this reconstruction was yet underway, Planning Your Neighbourhood did not include photographs but rather showcased vivid illustrations, all of which were based on the activities for which neighbourhood designers must provide.

This new, better Britain hinged on improving family life, and throughout Planning Your Neighbourhood, Goldfinger and Blackwell examined how post-war communities could be designed to support childrearing. Throughout the 1930s, the British birthrate dipped below that of competitor powers such as Germany and Japan.[4] Progressive reformers attempted throughout the interwar years to encourage family life to flourish in a number of ways. This goal continued throughout the war years with renewed fervour as the Beveridge Report expressed concern about Britain’s low birthrate. The report insisted that solving this problem necessitated ‘social expenditure to the care of childhood and to the safeguarding of maternity’.[5] British architects and planners thus began modifying the post-war home to position children at the centre of family life. This process of providing for children also extended to the larger community as open spaces began catering to children’s play and redeveloped urban sites and New Towns emphasised children’s activities and safety.

Goldfinger and Blackwell’s proposals, as presented in Planning Your Neighbourhood, were drawn from the County of London Plan (1943). Here authors John Henry Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie applied a concept known as the neighbourhood-unit principle to envision a planned London. As an ordering scheme, the neighbourhood unit provided urban planners with a framework for designing functional, self-contained and desirable communities. Its development has been attributed to the American sociologist and planner Clarence Perry, who first published the idea in the New York Regional Plan (1929). The neighbourhood-unit principle was a particularly child-centric method of town planning because Perry centred it on a primary school that had been scaled to serve a population of 5,000 or two primary schools that served 10,000. The school’s location also dictated the neighbourhood’s maximum area, as it would be situated so that children would not have to walk more than half a mile in densely populated districts. Forshaw and Abercrombie applied this concept to London, suggesting that London’s communities could be subdivided into neighbourhoods, each of which would centre on a school and would comprise 6,000 to 10,000 people.

Planning Your Neighbourhood explained this town planning concept to non-professional audiences by illustrating how planned neighbourhoods would integrate housing, schools, shops, employment, recreation and transportation to provide better landscapes for family living. Because Goldfinger and Blackwell intended for their display to reach a general audience, and because the family was integral to the notion of a neighbourhood unit, the designers employed a narrative device to make their ideas accessible by envisioning an imaginary family comprising a mother, father and two children to illustrate how modern planning principles would best support post-war childrearing and its associated activities. Five of the exhibition’s twenty panels centred on this family as they engaged in daily activities such as learning, working and playing.

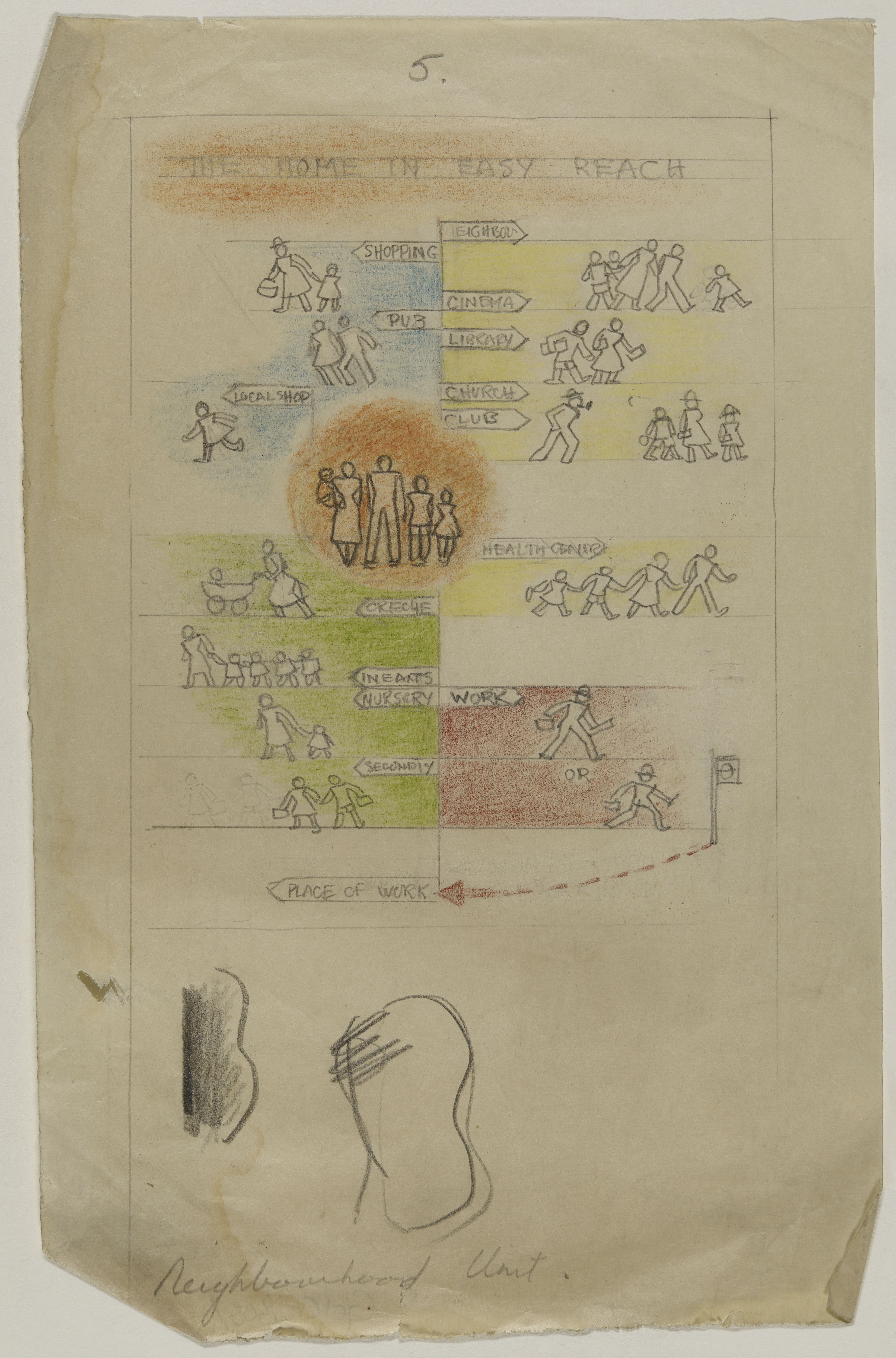

Lively cartoons by children’s illustrator Shiela Hawkins visualised this imagined family, revealing the relationship of children and their families to the larger neighbourhood through colour-coded imagery that helped exhibitiongoers follow the illustrated figures through their daily activities. To emphasise how re-designing urban areas according to the neighourhood-unit principle would impact children, these drawings revealed how young people studied, played and travelled within the city and demonstrated that spaces should be tailored to enable their development. The exhibition’s fourth panel attempted to clarify the definition of ‘planning’ by explaining that it meant ‘schools, shops, work, and recreation within easy reach of our home’.[Panel 4] Here Hawkins’s illustrations depicted the family at the centre of the panel inside a red circle. Arrows radiated from this circle to indicate the travel of various family members to different places to undertake activities. Alongside parents, who engaged in childcare and paid employment, Hawkins depicted children visiting shops, a health centre, schools, playing fields and the cinema. Since each family member appeared in red, both at the centre of the panel and in each of the surrounding activity bubbles, exhibitiongoers could follow the narrative of the display. Although Hawkins produced each illustration, a preliminary sketch from Goldfinger’s archive in a different hand reveals that Goldfinger and Blackwell devised this narrative and its arrangement by showcasing the family at the centre of a composition that saw the figures surrounded by their engagement in various activities around the neighbourhood.[6]

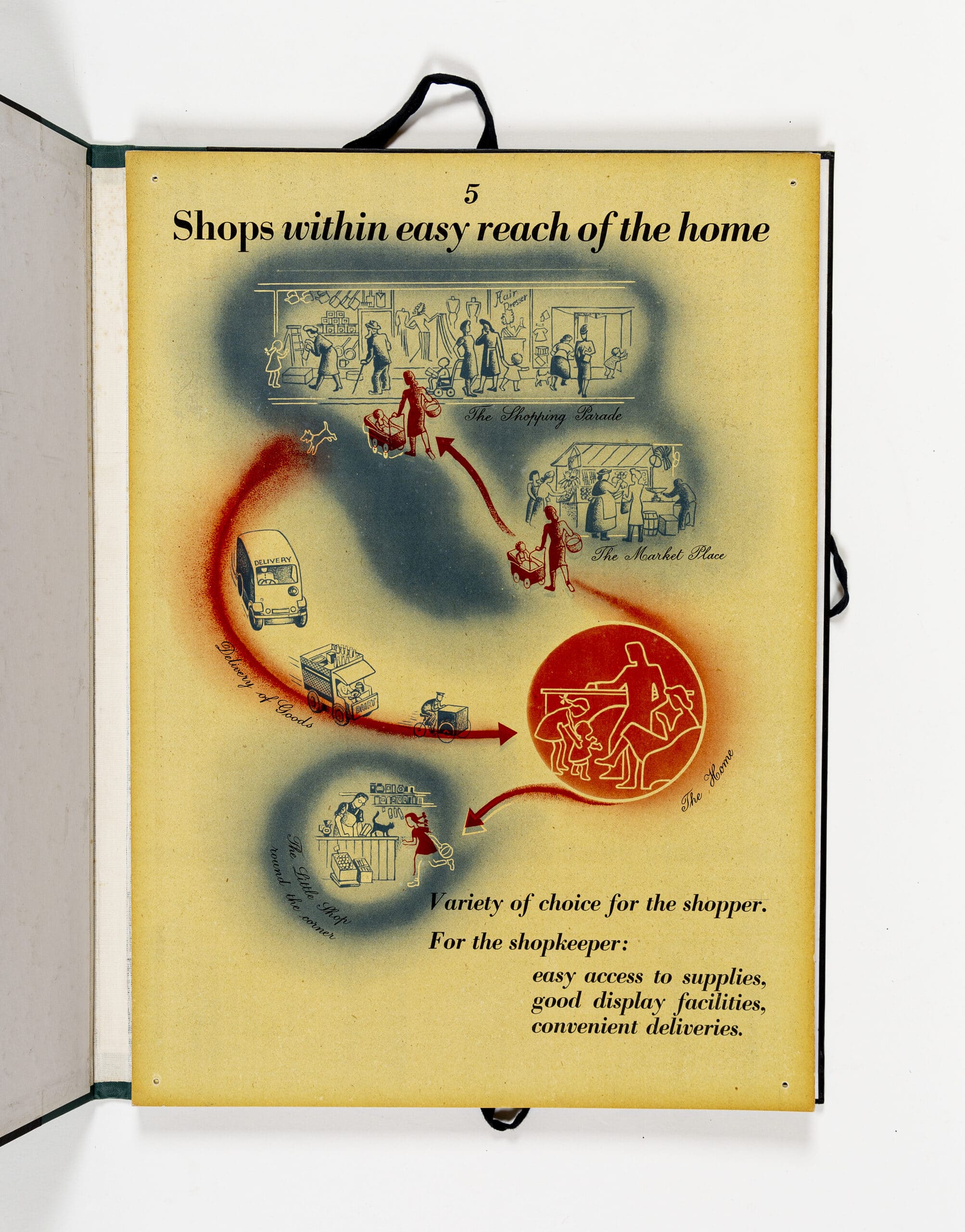

In addition to highlighting Hawkins’s adept rendering of childhood activities, the exhibition panels demonstrate a clear connection to Goldfinger’s earlier work designing toys, retail displays and exhibition stands for toymakers Paul and Marjorie Abbatt. Goldfinger did not see this type of work as separate from his architectural practice, as he viewed himself as someone who engaged broadly in manipulating space. Moreover, he became very interested in shaping environments that children could handle independently after observing his own children’s engagement with the world.[7] Drawing from these projects, Goldfinger and Blackwell foregrounded features that fostered childhood independence as integral components of a functional neighbourhood. For example, panel five depicted the types of shops that people should be able to access easily: a shopping parade, marketplace and corner store. While the mother and younger child travelled together to the more distant shopping parade and market, the ‘little shop around the corner’ was proximate enough to the home as to allow the family’s older child to exercise her independence by shopping on her own.[Panel 5]

Panel six reinforced the idea that the child should explore her neighbourhood by showing the same figure heading to school with a group of friends. In an article titled ‘For the Family A House, A Flat or Something between the Two’, published in the September 1942 issue of Ideal Home, Goldfinger insisted, ‘It is of first-rate importance that in urban agglomerations children (even up to the age of 10) should not be obligated to plunge into the sea of traffic, and it would also be desirable that schools should be in the proximity of the family dwelling’.[8] This panel highlighted traffic safety by insisting that children should not need to cross traffic on their ways to school—a point that would extend to children travelling to corner shops or recreation space.[Panel 6]

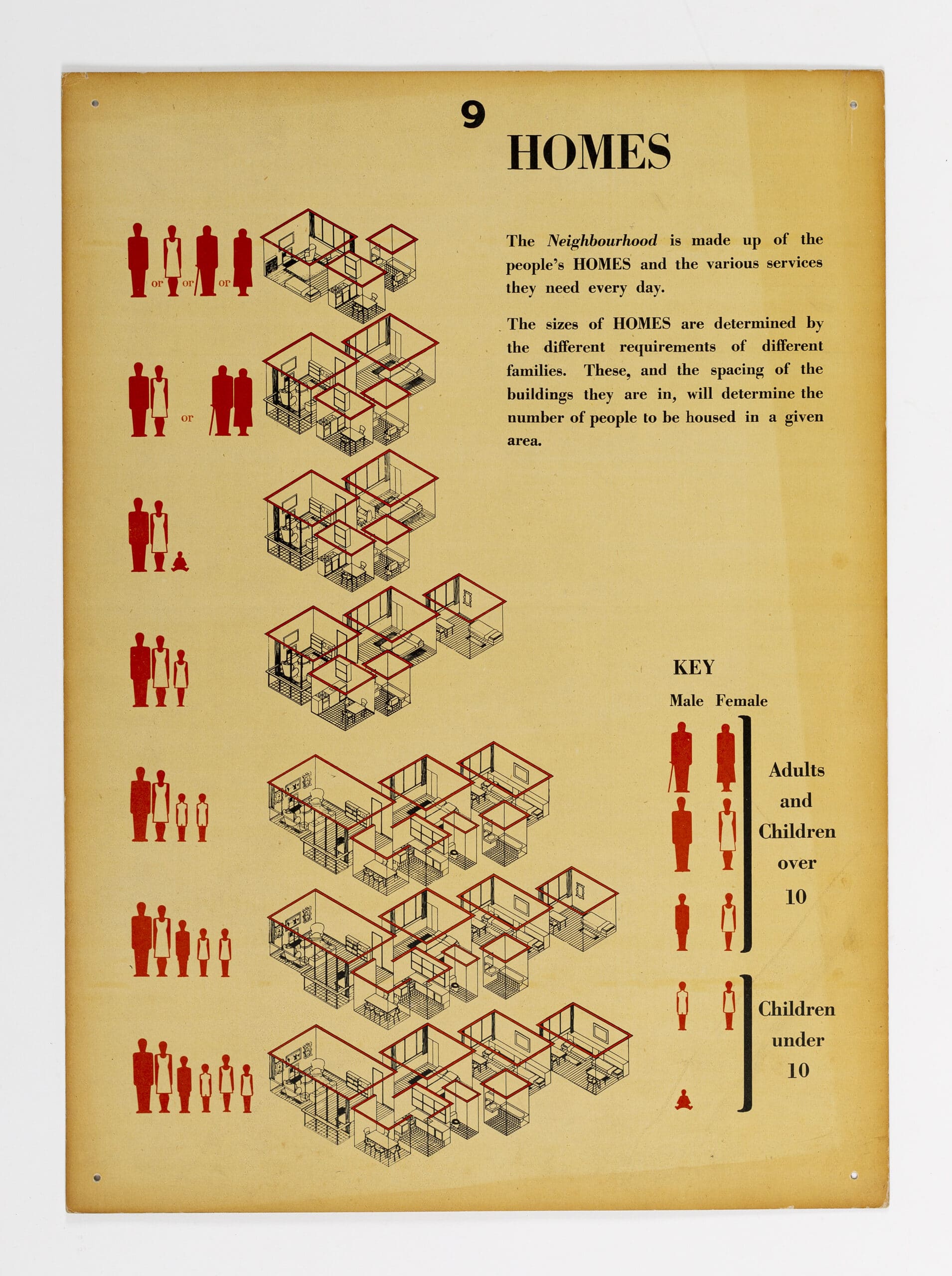

Planning Your Neighbourhood also extended to proposals for homes. Goldfinger advocated multi-storey development for urban areas, in order to provide play space for children while supporting densities that would keep homes close to schools. On panel nine of Planning Your Neighbourhood, Goldfinger and Blackwell showed how the size of a family should determine the size of the dwelling.[Panel 9] Here the two designers illustrated the relationship between family and dwelling by representing men, women and children using Isotype (the International System of Typographic Picture Education), a system for visualising historical, social, biological, and technological connections in pictorial form. Developed in Vienna by Austrian sociologist Otto Neurath in 1925-34, the use of Isotype spread throughout Britain after Neurath settled there. The Ministry of Information and other official bodies used Isotype widely throughout the war to disseminate information. The adoption of Isotype in Britain reflected a wider trend during the 1930s and 1940s to apply modernist principles to all areas of graphic design, ranging from typography to posters, to make information more accessible to a greater number of people—a goal that was reflected in ABCA’s aim of improving adult education. By using conventionalised figures that were characterised by flat planes of colour and accompanied by bold typefaces, Blackwell and Goldfinger ensured that exhibition visitors could digest complex statistical information at a glance. In this respect, the displays adhered to ABCA educational norms because they did not require any specialist knowledge in order to be understood. Moreover, Blackwell and Goldfinger’s use of Isotype demonstrates that the artist and architect were broadly interested in new design ideas.

By translating the content of governmental policy documents from the textual to the visual, and by grounding it in the familiar territory of the family home, Goldfinger and Blackwell aimed to legitimise and widely disseminate the ideas found within so that audiences could understand basic modern planning principles and demand a planned reconstruction. In so doing, they harnessed visual techniques that aimed not to simplify architectural ideas conceptually but rather to make them accessible to audiences by illustrating how families would occupy new neighbourhoods and homes to show British citizens how modern planning could help them live better lives. At the same time, Goldfinger used Planning Your Neighbourhood and other exhibitions to showcase his approach to modernist architectural practice, which he applied consistently throughout his career. By paying attention to the environment Goldfinger consistently applied aesthetic principles across scales and his practices necessarily bridged disciplines as he designed objects, housing and neighbourhoods.

Notes

- Sir William Beveridge’s speech at the opening of Rebuilding Britain, reprinted in ‘The Opening of the ‘Rebuilding Britain’ Exhibition’, Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (March 1943), 99.

- Lord Latham, ‘Foreword’ in J.H. Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie, County of London Plan (London: Macmillan and Co. Limited, 1943), iii-iv.

- Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr/405/1, RIBA Archives.

- Elizabeth Darling, Re-Forming Britain: Narratives of Modernity before Reconstruction (New York: Routledge, 2007), 52.

- William H. Beveridge and the Inter-departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, Social Insurance and Allied Services (H.M.S.O., 1942), 8.

- Preparatory sketch for Planning Your Neighbourhood. Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr/405/1, RIBA Archives.

- Ernö Goldfinger quoted in ‘Arthur Lawson Looking Round in Town To-Day’, Star (8 January 1938). Ernö Goldfinger Papers, GolEr/389, RIBA Archives.

- Ernö Goldfinger, ‘For the Family a House, a Flat or Something between the Two’, Ideal Home (September 1942), 131.

Dr Erin McKellar is Assistant Curator (Exhibitions) at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London. Here she leads the online exhibitions programme and curates shows in the gallery on modern and contemporary architecture. Her exhibitions reveal how Soane’s ideas are reflected in 20th- and 21st-century design. Her independent research centres on the design cultures of the 1930s and 1940s.