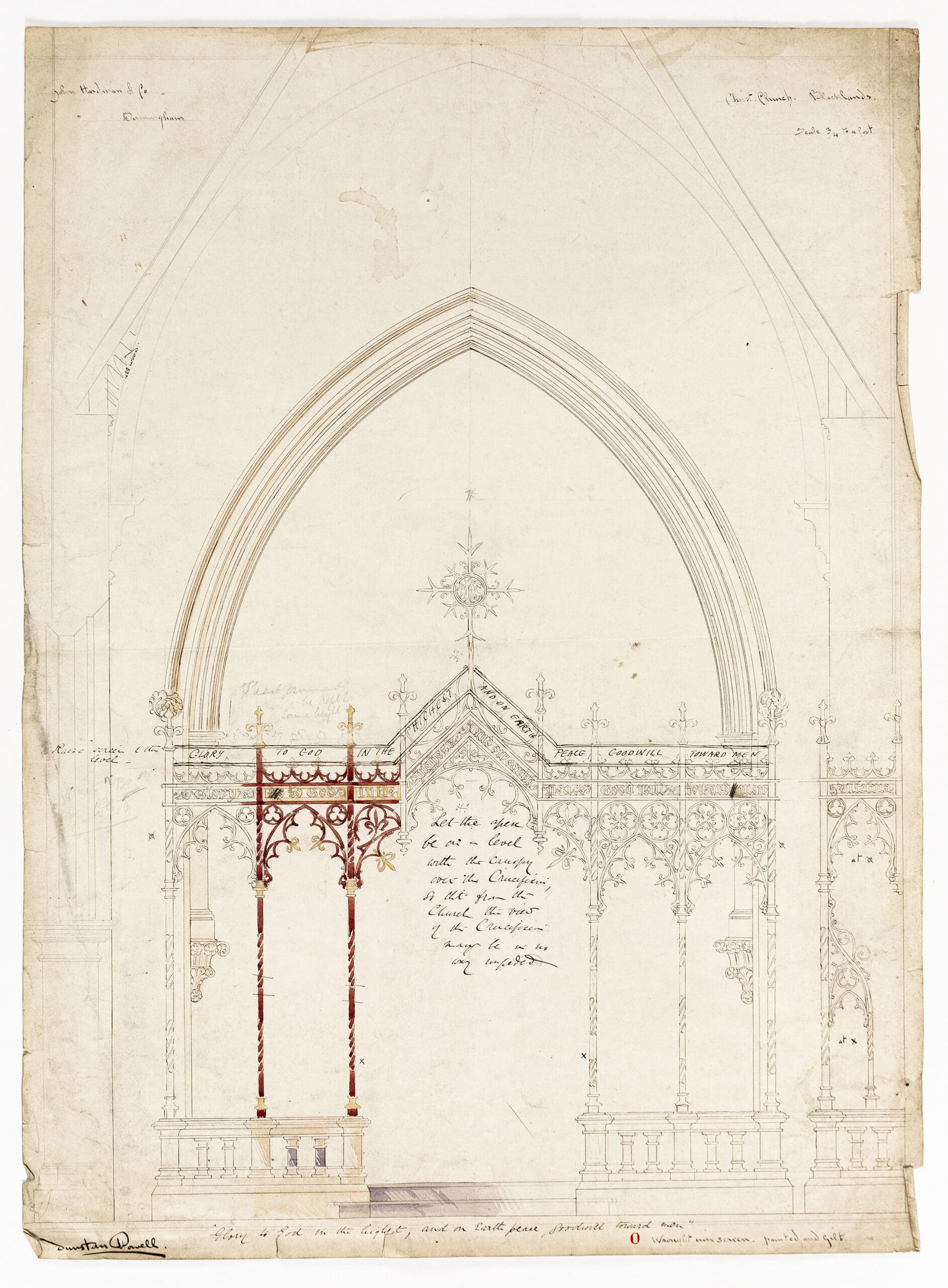

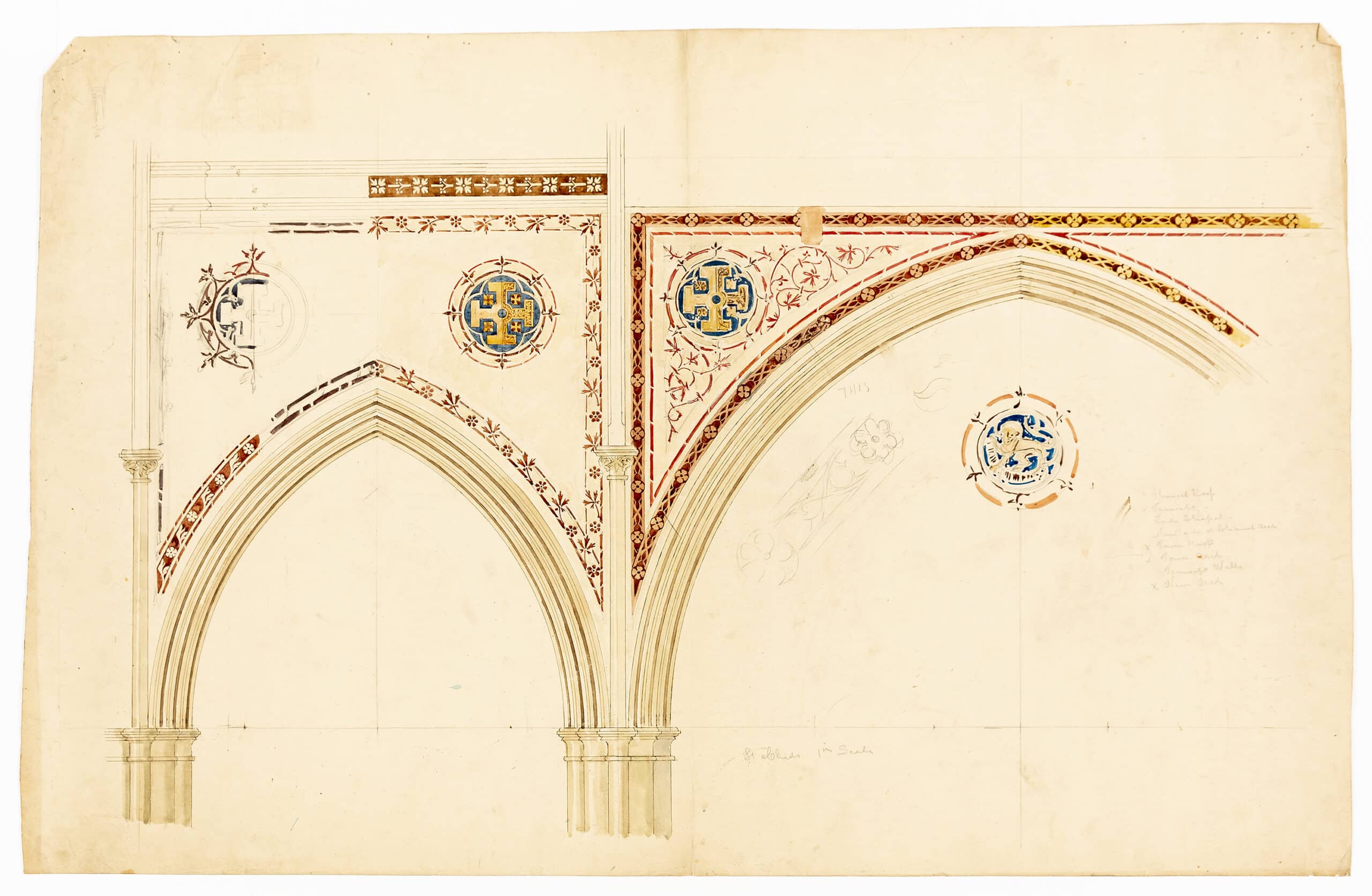

Hardman & Co.

My interest in seeing the Hardman & Co. drawings at Drawing Matter was quite personally motivated as I feel a connection to the company. Partially, because I come from Birmingham where the company was based, and because I visited the studios informally in the 1980s with my parents. I was an art student wanting to specialise in stained glass, and my dad worked in architectural salvage.

We visited when the company was in Lightwood House in Smethwick—a grand late-eighteenth-century house. The company had moved there after their previous studios had been destroyed by fire in the 1970s (Frederick St or Newall Hill, I think?). My dad had bought salvage from the fire and knew some of the glassmakers, who agreed to show us round. He also knew the new owner of Hardman’s who had bought the company sometime after the fire. He was an antiques dealer with no longstanding connection to the company heritage. I don’t think he was well respected, and the impression was that he ran the company down.

I was idiotically shy when we visited and didn’t have the courage to ask questions—I was able to hide behind the rapport my dad had with the glassmakers. I remember some things clearly. The workshops were in large spaces and there was a room of pattern books treated in a casual way, considering the prestige of the projects. They weren’t disrespected so much as handled as everyday working objects. The man showing us round thumped them on top of each other or dragged books roughly from the bottom to the tops of piles. I also have an impression of them being on the floor and stepped around or across to get from one part of the room to another. One thing I did ask was how they managed modern design. His answer was funny: he said they preferred traditional themes because they were easier to design. He said it was harder if they were asked to sum up an abstract theme in glass.

Through my parents, and because of my own practice in glass some years later, I kept in touch with one of the workmen called Frank Whelan. He was retired then and used to like to come to my studio and reminisce. He would tell me stories of churches he’d worked on, and how beautiful the glass was. My dad remembers him working, and his special skill was how fast he climbed to fit or remove glass from the stone tracery.

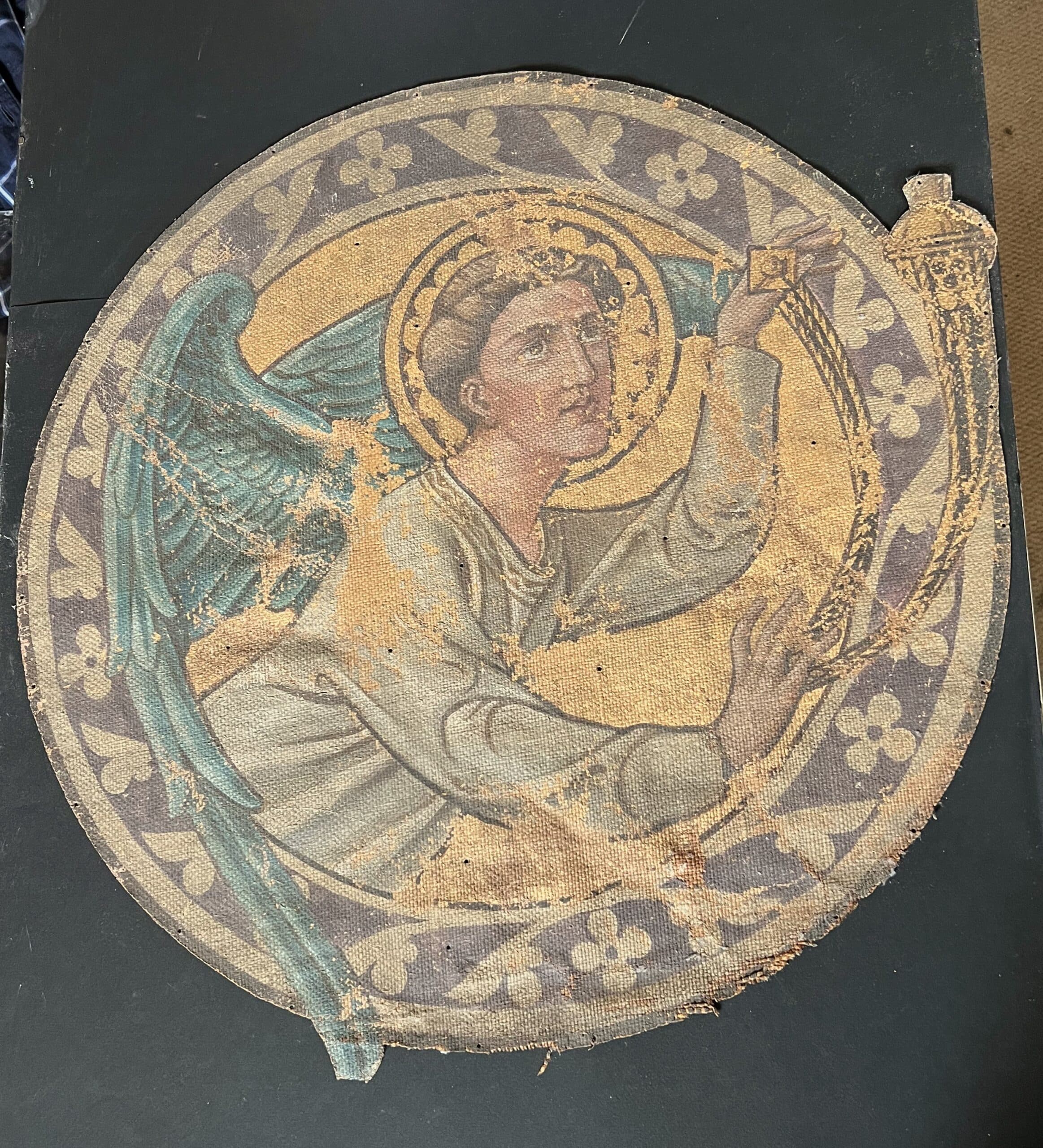

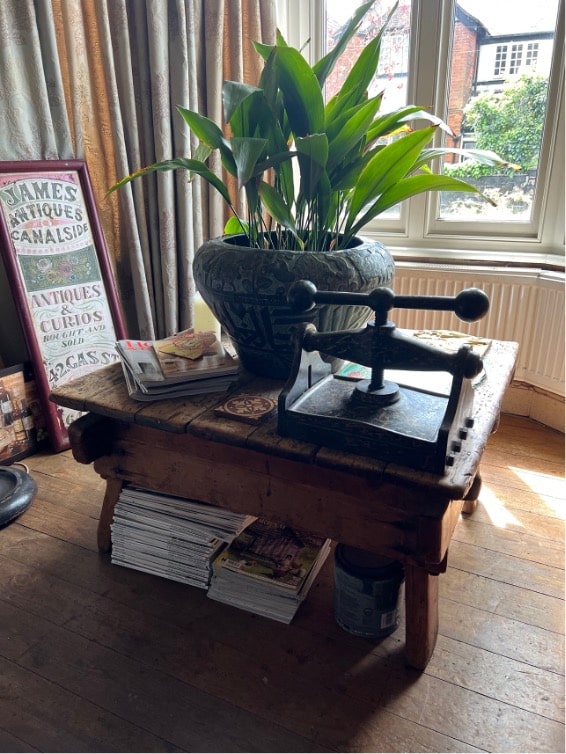

As an aside, I have included some photographs of a couple of things my dad bought from Hardman’s after the studio fire. He was asked in by the demolition men towards the end of the clear up. Everything of high value had been removed. He bought up quite a lot of these canvas cartoons that were in a rough state, and the low workbench which is a sculpture table. All the other cartoons were sold but he kept this one and the table.

I am not sure, but I think the cartoon may be a painting plan used to trace painted glass over. There are nail marks all over it where I wonder if pieces were held in position for painting. I have some doubts if this is correct, because firstly the pattern does not show lead lines, but this may be because they were decided at a different stage of manufacture. Also, the quality of painting is very high, and the background is gold—I can’t see why they would use gold on a working cartoon. There are traces of plaster on the back of the canvas, and as Hardman’s undertook all sorts of ecclesiastical work from metal work to glass it might be another type of decoration all together. However, my understanding has always been that it is a cartoon for glass.

Sarah James visited the Drawing Matter collection with Master of Research (MRes Arts) and Master of Architecture (MArch) students from Arts University Bournemouth in April 2023.

– Rosemary Hill