Het woonpalazzo – The Residential Palazzo

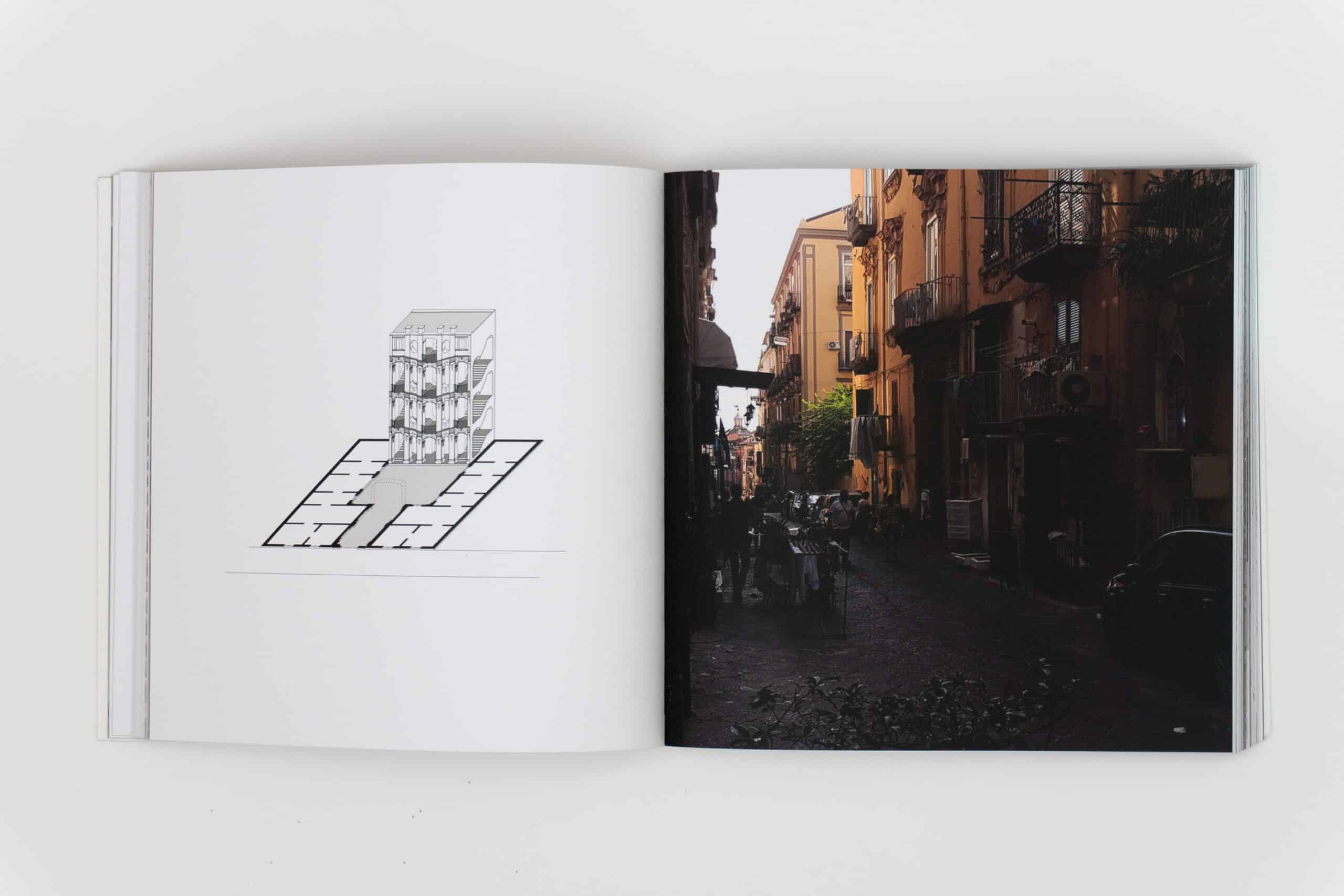

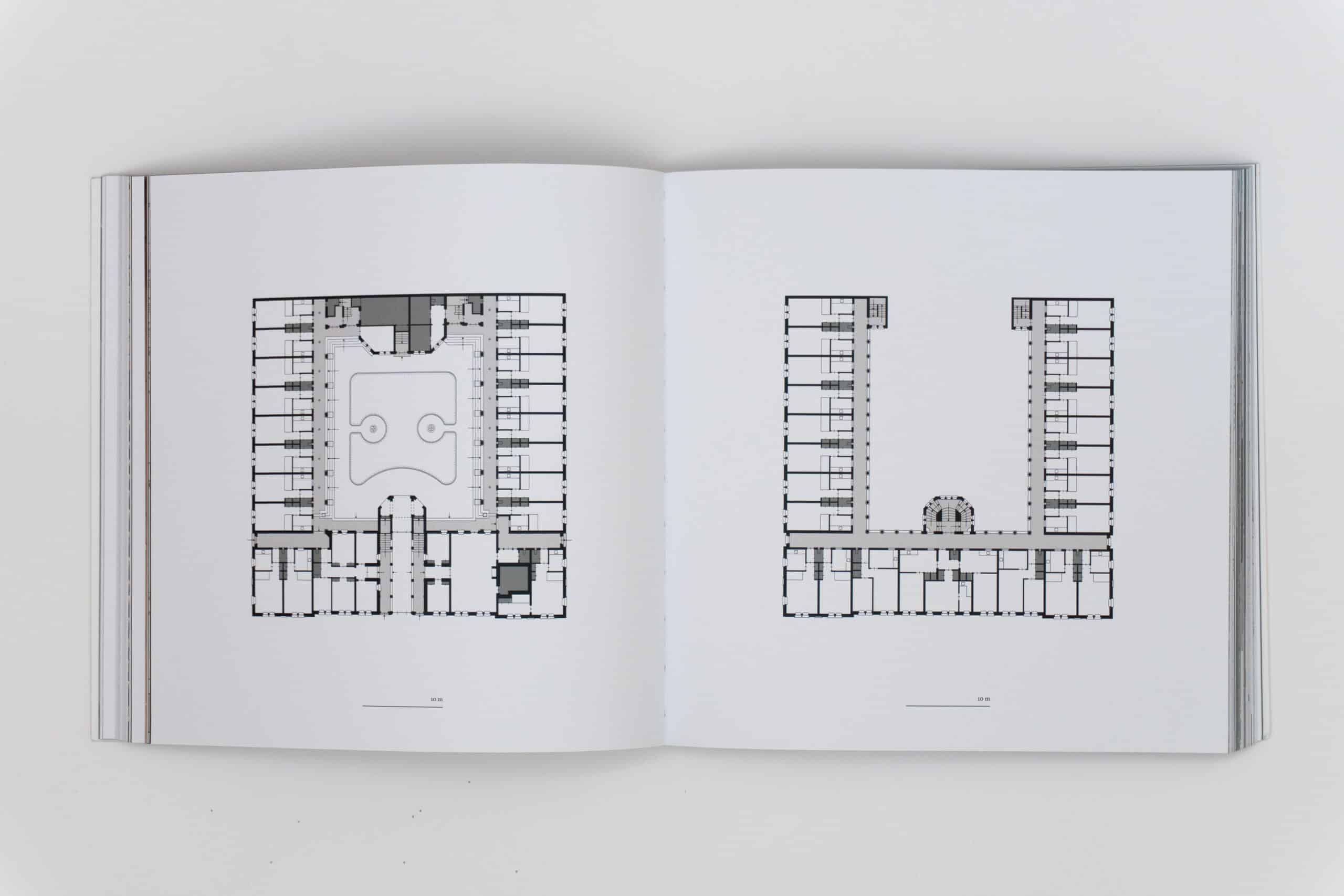

Open any book by a Dutch architect and you are bound to come across H. P. Berlage—the forefather from whom sprang everything, albeit indirectly, from the Amsterdam School to Der Stijl and who is revered for his contribution at all scales from the details of his buildings to his town planning. He is celebrated in the very first sentence of Hans van de Heijden’s The Residential Palazzo for the fruits of his 1880 study trip where he analysed ‘the patrician palaces in Genoa’, not for their sophisticated stylistic manipulation, but as a formal typology with practical lessons for his contemporaries; these remain relevant for architects in the twenty-first century. Renaissance palazzi were inserted into the medieval fabric of Italian cities, bringing a welcome order to their fabric: Sangallo’s 1489 Palazzo Gondi in Florence (extended in 1874) is a prime example. Van der Heijden wants to show how the palazzo form can do the same for the urban inheritance from the twentieth century and has constructed a matrix for his students, illustrating how the typology allows for high densities but creates compact courts. In Amsterdam, he studies Lutherhof, a home for single women by a little-known contemporary of Berlage’s, Dirk van Oort, and, bringing his thesis closer to today, Diener and Diener’s Hofhaus; finally, he illustrates projects, by his office, built and unbuilt, and from 2014 by his students. All of his and his students’ examples ‘resist the trivial’, he explains, while acknowledging the necessary disjunction of façade from structure for environmental reasons; Frampton’s position on tectonic expression can no longer be sustained, but that does not mean that anything goes. Every proposal must be rigorously examined and justified, from its position in the urban context, to the re-interpretation of the type in plan and section, to the construction of a typical bay and the details of its projections and recessions. In describing his students’ work, van der Heijden shows how the self-conscious adoption of the residential palazzo type can inform designs by those with differing architectural enthusiasms and from different backgrounds: it is not a culturally conditioned Eurocentric form, he claims, but widely applicable. The close study of the type acts as an antidote not only to stylistic fashions but also to an exclusive concentration on atmospheres, recalling architects to a self-imposed duty to be fluent in their use of a formal repertoire.

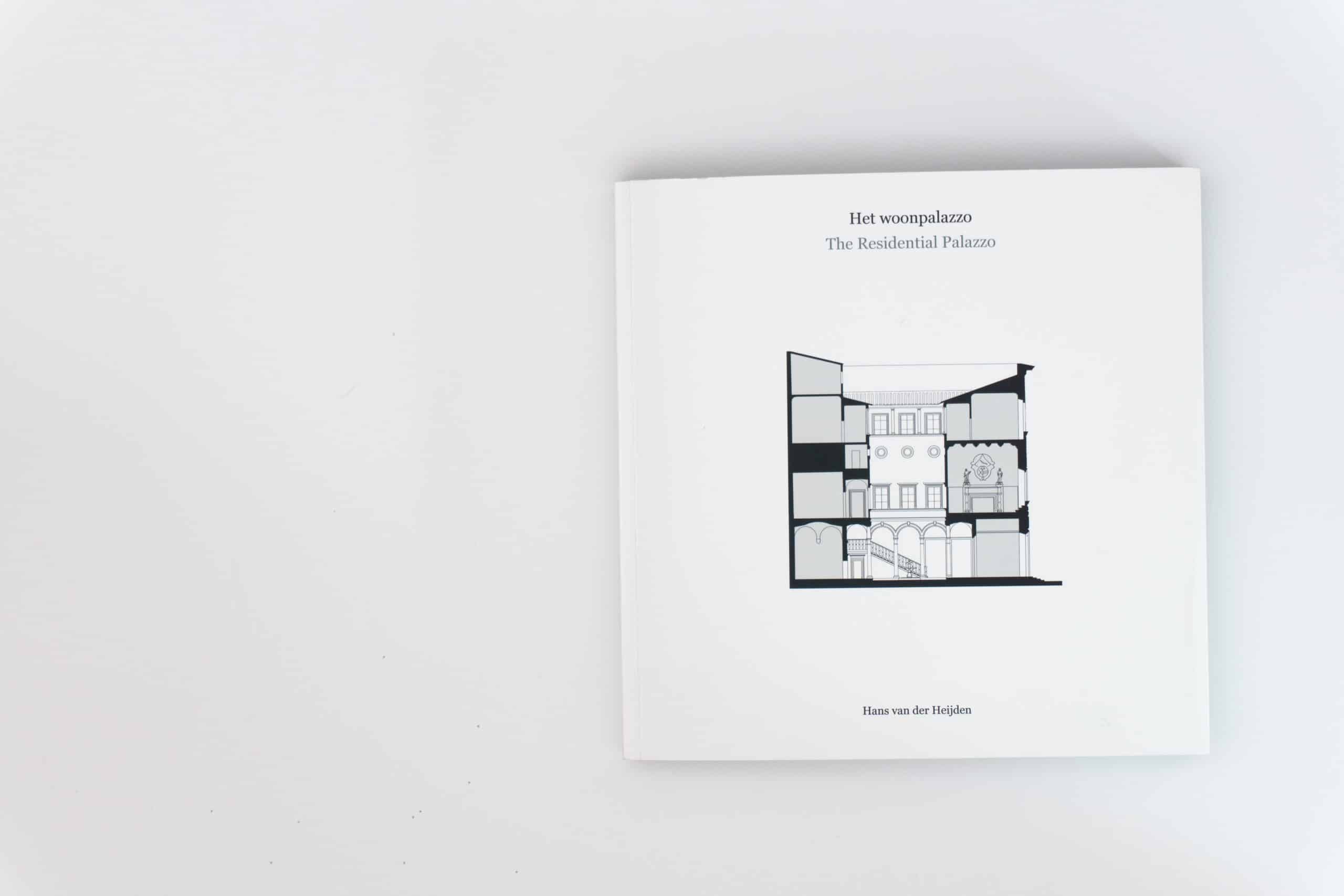

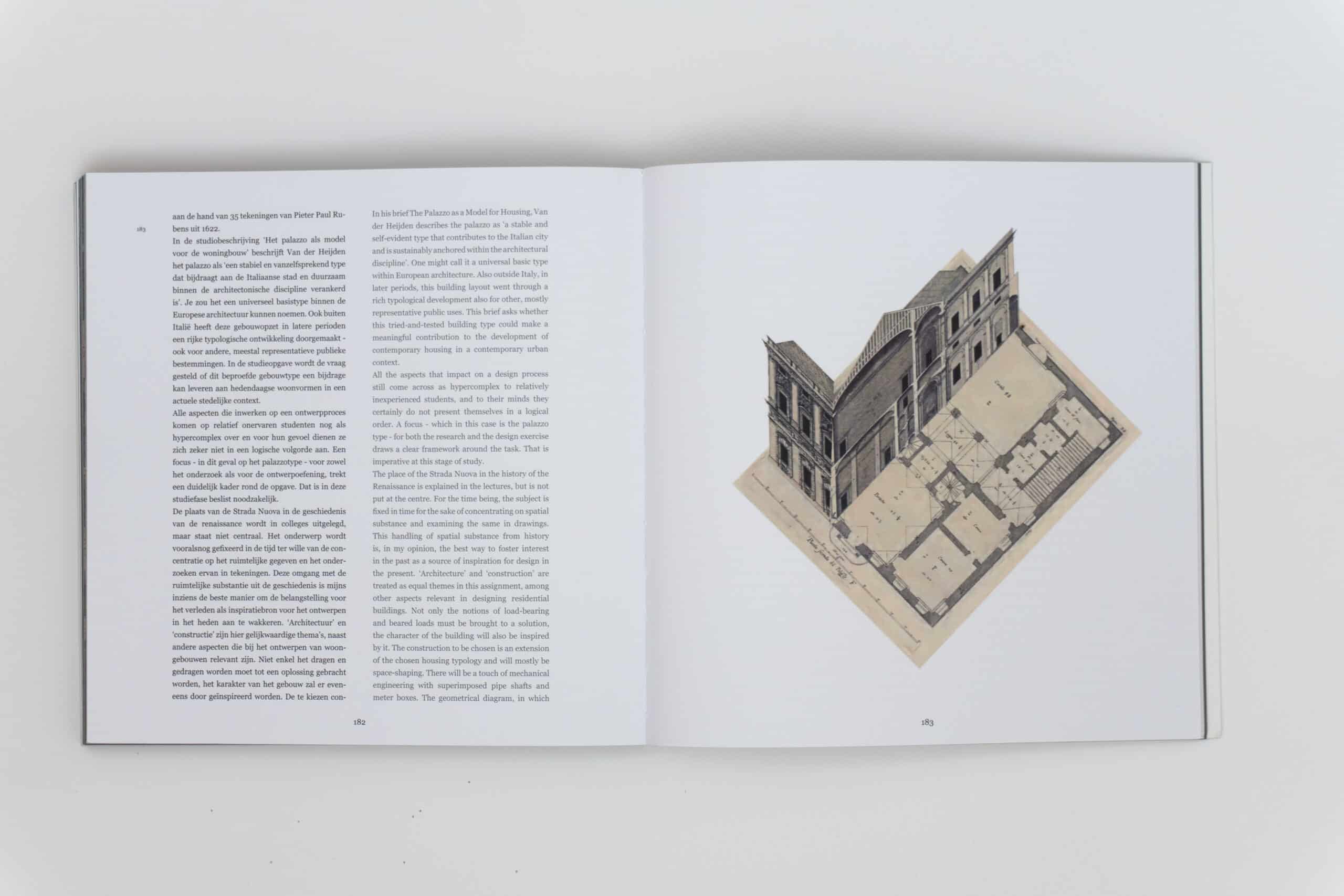

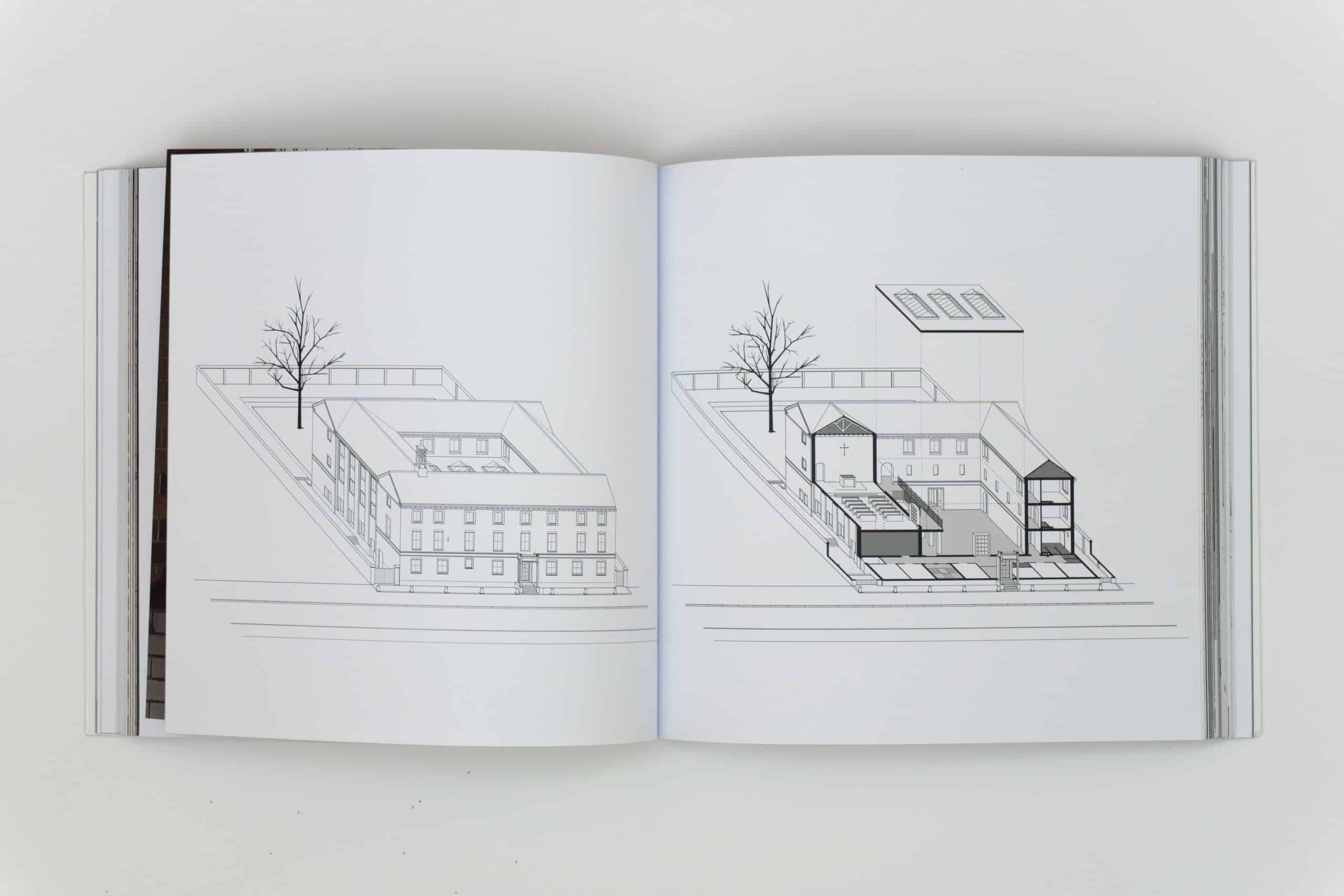

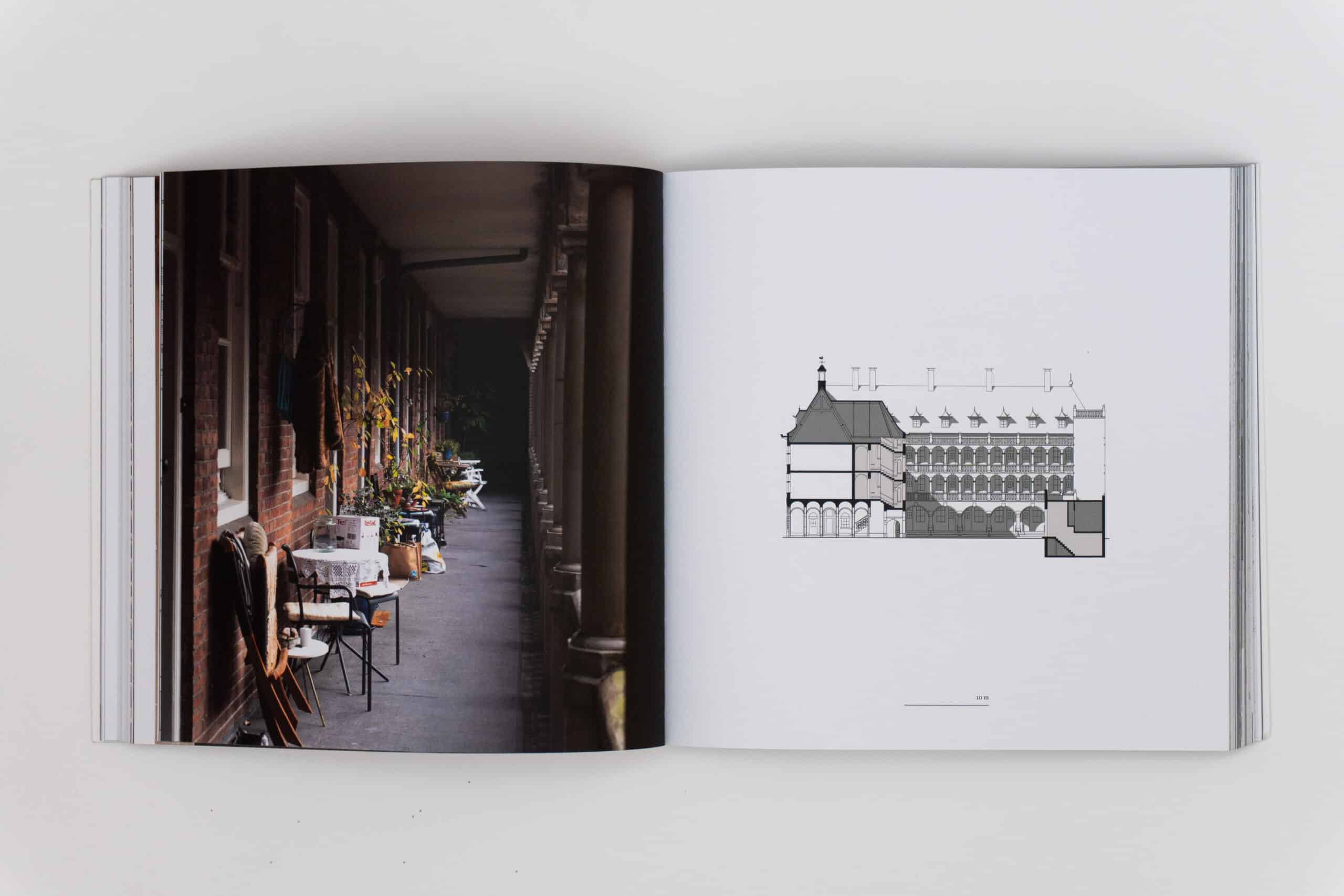

As might be expected, the thesis, which is conveyed in a 36-page essay in Dutch and English, is illustrated by consistently rendered drawings: plans, sections, and analytical axonometrics. The latter are modelled on an idealised set of drawings of Genoese palaces done under the supervision of Peter Paul Rubens from 1622. The presentations are supplemented by photo-realistic computer-generated images and diagrammatic perspectives. An aspect of the palazzo typology that particularly intrigues van der Heijden is the treatment of staircases. They can be embedded in the fabric of buildings that surround a court or, as in Neapolitan examples such as the Palazzo Constantino alla Costiglioli, expressed within the court. The stairs at the Lutherhof are particularly striking, rising in symmetrical flights on either side of a generous ‘androne’ to appear prominently in the courtyard. In the 1956 monastic Fraterhuis, by Jan van der Laan, with a glazed covered court, they are deliberately suppressed within the plain surrounding fabric.

Van der Heijden’s study of lessons that can be abstracted from historical examples to order the thinking of architects and architectural students revives an attitude that was more common in the second half of the twentieth century than it is today. In 1960, Tom Ellis wrote a brief influential article entitled ‘The Discipline of the Route’. Ellis was a partner of Lyons, Israel and Ellis, the practice that nurtured James Stirling and James Gowan, Neave Brown, Eldred Evans and Alan Colquhoun among others. He was also, like van der Heijden, thoughtful and self-reflective. In his article, he described how buildings by Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto were disciplined by the route: first, architects show you the organisation of the building and then they exploit the drama of ramp or staircase. The first examples he refers to are Renaissance palaces. Once you enter,

The number of floors of the palace can be seen at one glance the importance of the varying floors recognised and the destination noted. The staircases are invariably in the corners of the courtyard and are dogleg, so that on arrival at the first floor you are immediately above the point where you started and recognise the courtyard – therefore the position is known… The doubling back of the dogleg staircase is the key to the way in and the way out in that the same thing is seen in both directions.[1]

What is missing, or at least under-emphasised in Van der Heijden’s account, is how the typology can encourage spatial appropriation. Herman Hertzberger (another admirer of Berlage) talked of buildings being ‘adhesive’ and suggested architects could provoke activities, such as conversation between people on stairwells, by the forms they used. A photograph of the gallery at Van Oort’s Lutherhof shows the way substantial masonry and spatial generosity allow such appropriation. The drawings of Van der Heijden’s and his students’ projects are purged of the paraphernalia of inhabitation, and so are photographs of recently constructed buildings. This is not a matter of style or atmosphere: architects and teachers need to show that a return to a rigorous formal discipline, in practice and in the teaching of architectural composition, need not come at the expense of everyday occupation: most people are naturally less interested in the manipulation of a repertoire that the best architecture of all periods can be shown to exhibit, but simply wish to enjoy its fruits.

Notes

- Tom Ellis, ‘The Discipline of the Route’, Architectural Design, November 1960, 481-2.

*

Nicholas Ray is an Emeritus Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge, and a Visiting Professor at the University of Liverpool.

Find out more about Hans van der Heijden’s Het woonpalazzo – The Residential Palazzo (Amsterdam: HvdHA, 2025) here.

– Editors