In the Archive: Riefenstahl, Hitler, Ebhardt, Sironi, Brasini

– Editors

Click on drawings to move and enlarge.

Premiered at this year’s La Biennale di Venezia, was Andres Veiel’s documentary on Leni Riefenstahl, the German film director known for Olympia (1936) and Triumph des Willens (1935). Framed through archival material Veil’s Riefenstahl (2024) demonstrates how her work was inextricably linked to the Nazi regime. The filmmakers had unprecedented access to her estate, with over 700 boxes of her private films, photos, letters, and recordings, which they used to uncover what she publicly denied for years.

With the release of Riefenstahl, we are reminded that archives are not neutral places, they are to be dissected and analysed by researchers. Having this in mind, we looked at our archive’s related materials, which holds a small selection of drawings associated with fascist artists and architects.

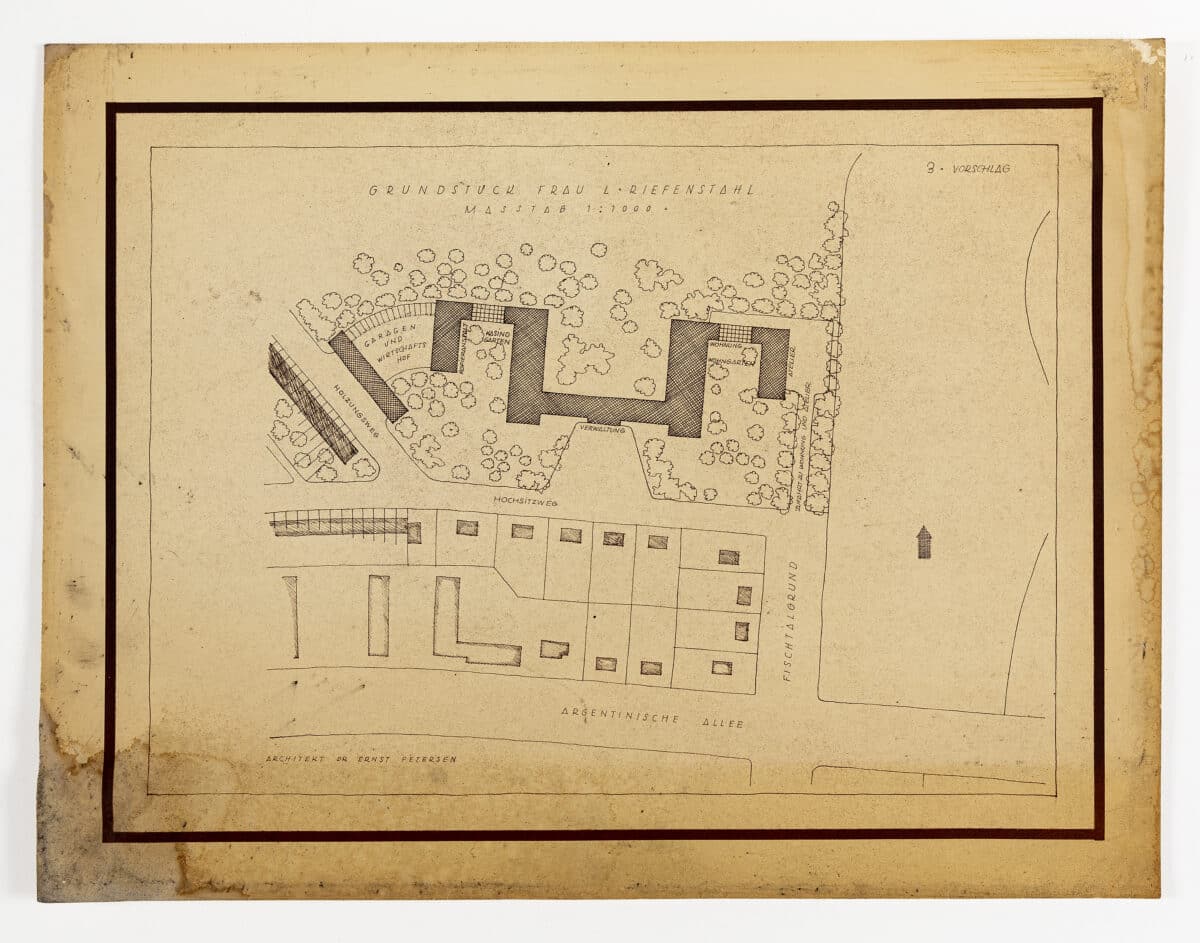

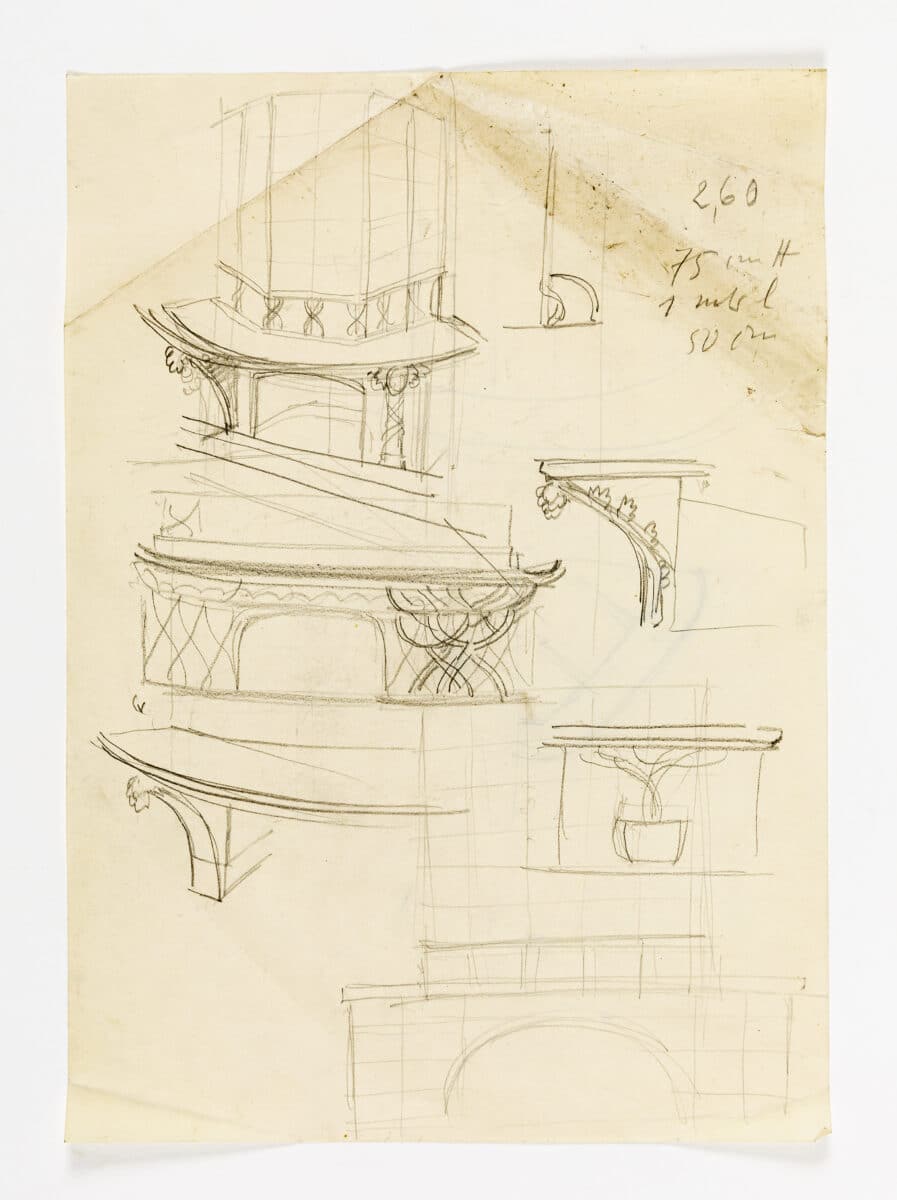

In the collection, are sketches and plans of Riefenstahl’s villa in Dahlem, Berlin designed by actor-come-architect, Ernst Petersen. The palatial and ornate house was visited in June 1937 by Adolf Hitler and his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, in an act of support for Riefenstahl’s film Olympia, made for the 1936 Berlin Games. They were also accompanied by Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer, who shot the meeting. They group is captured looking around the garden, shaking hands, and taking lunch outside.

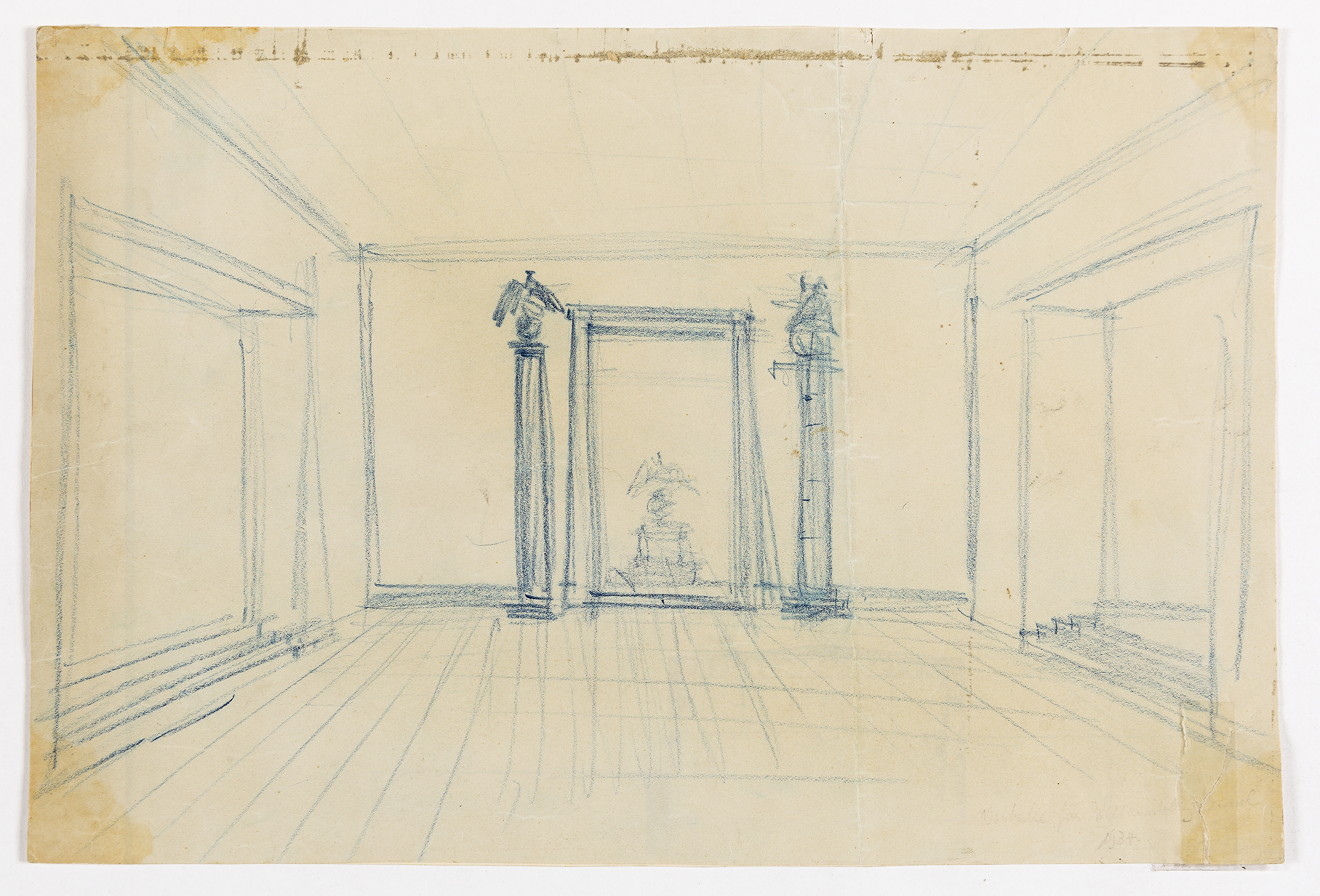

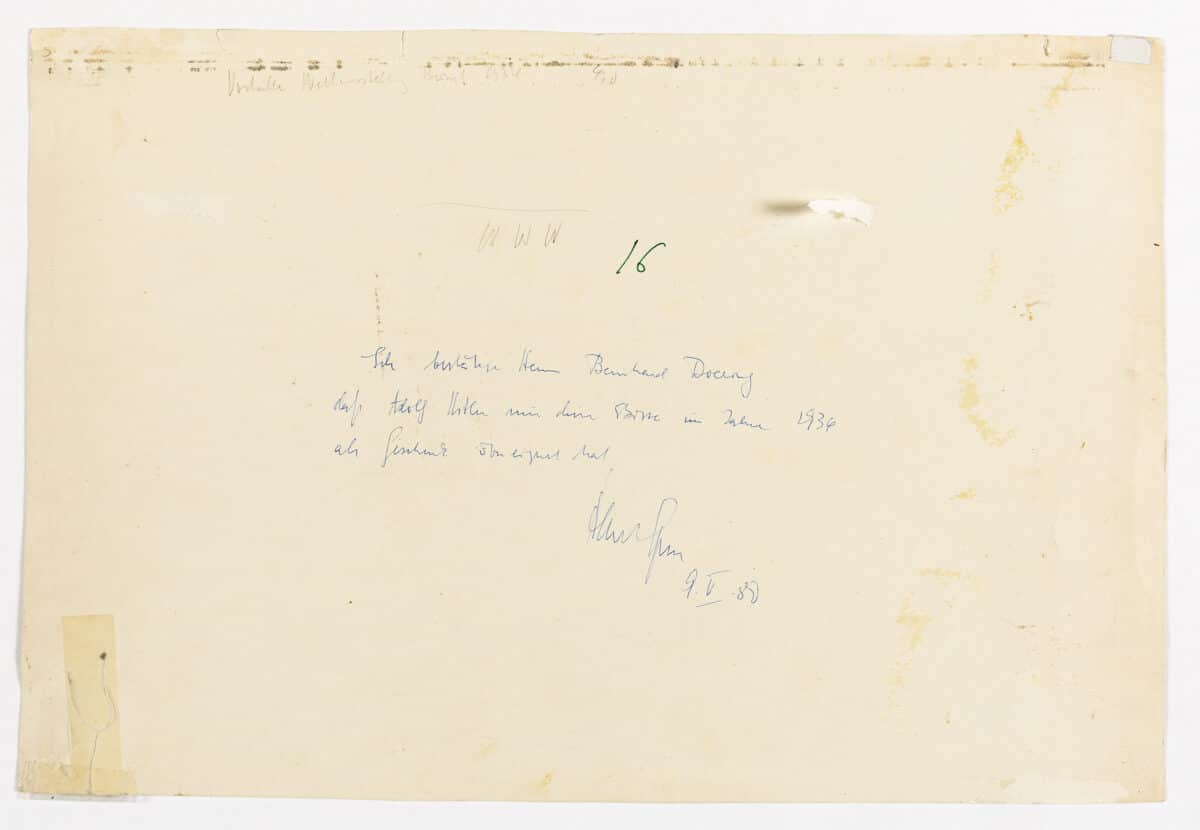

Hitler also features in the collection, with a design concept for the German room at the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair. The National Socialist government invited six architects, including Mies van der Rohe to design the German Pavilion. The brief included some specific instructions, for example, the compulsory inclusion of the swastika—the design needed to represent the new regime, both politically and economically. Hitler works out in a blue crayon, the placement of two classical columns topped with eagles; this motif was used in the final design by Hitler’s favourite architect Albert Speer.

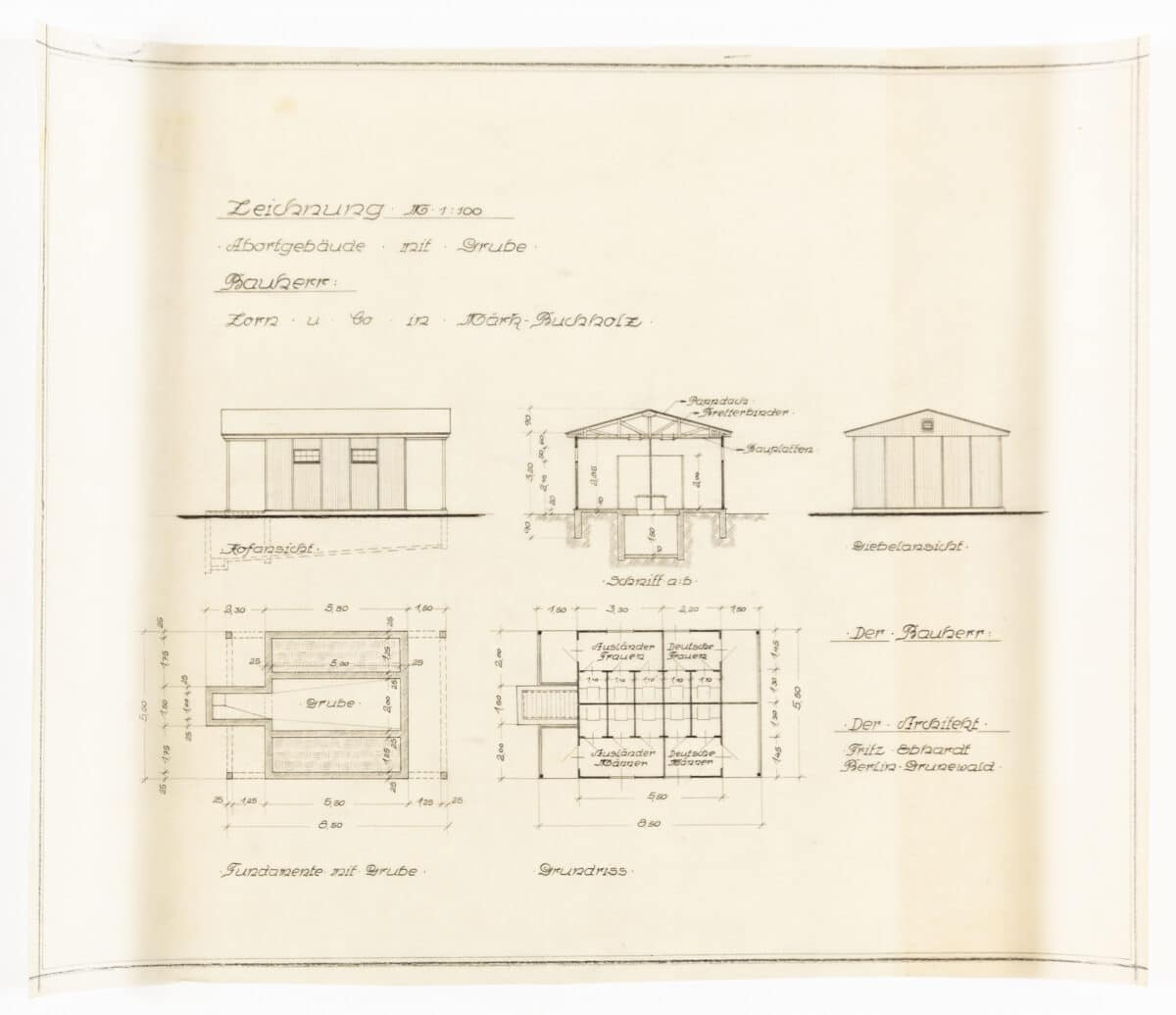

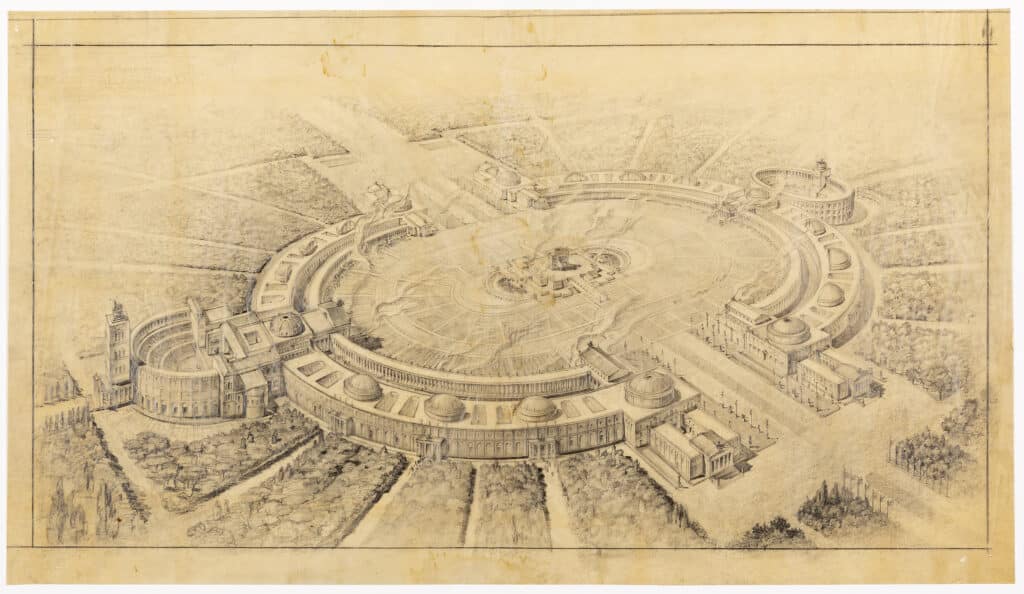

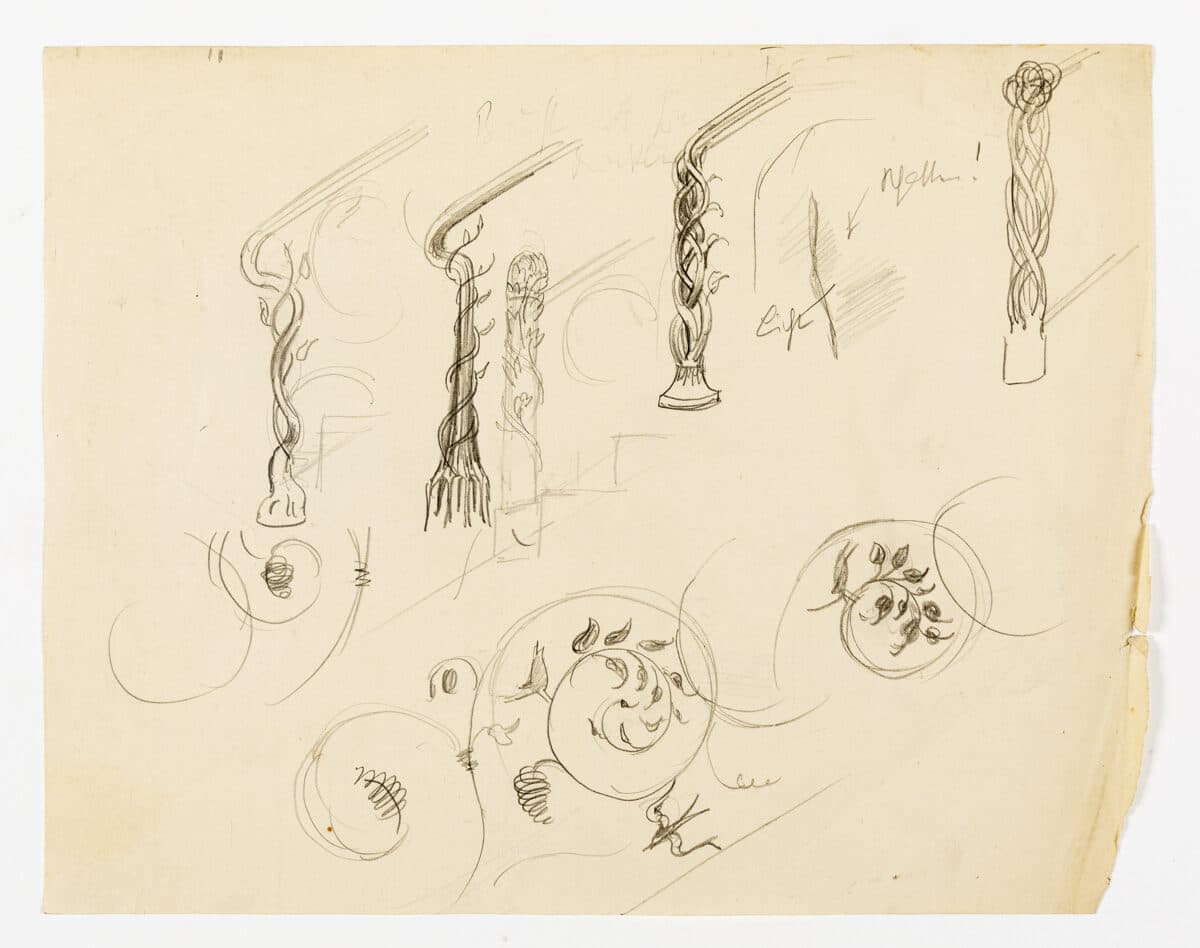

Also shown on the planchest are Fritz Ebhardt’s plans for an armaments factory, Mario Sironi’s drawings for the Fiat Pavilion, and Armando Brasini’s design for a stadium. Nazi architect Fritz Ebhardt specialised in repetitive and extendable designs with stark, industrial forms that could be applied in this case to an armaments factory, but also more devastatingly to concentration camps. Mario Sironi led the aesthetics behind Mussolini’s l’Uomo Nuovo (the New Man), making his monumental fascist image concrete in his architectural and mural commissions for the Fiat Pavilion, exhibited at the 1936 VI Triennale di Milano. Armando Brasini, another favourite of Mussolini, proposes in this aerial perspective, a stadium in the image of Imperial Rome to honour their German allies. In trying to find a style for their politics, Brasini collages together recognisable classical forms, from the Brandenburg Gate to the Colosseum.