Inessential Colors: Architecture on Paper in Early Modern Europe (2021) – Review

From the frescoes of Pompeii to the Great Hall of Siedlecin, from the Book of Kells to the Book of Hours, architecture has been depicted in full colour. Where colour has been largely absent in the history of architectural representation, however, is in the more technical drawings of architects themselves. Here, monochromatic depiction was the norm until the seventeenth century when, under the influence of cartographers, architects began to develop colour ‘conventions’ to indicate section cuts and facade materials, conventions that lasted throughout the reign of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

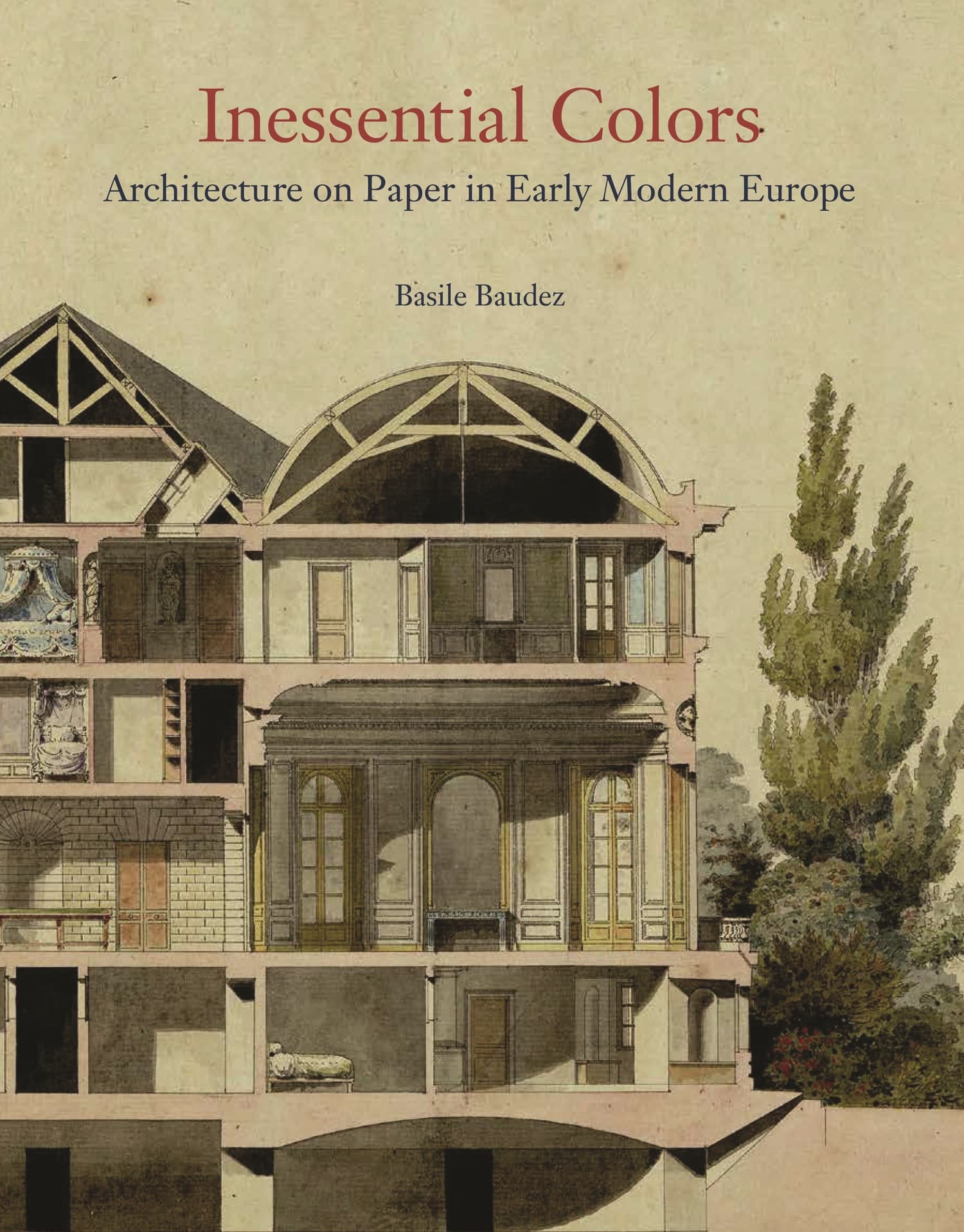

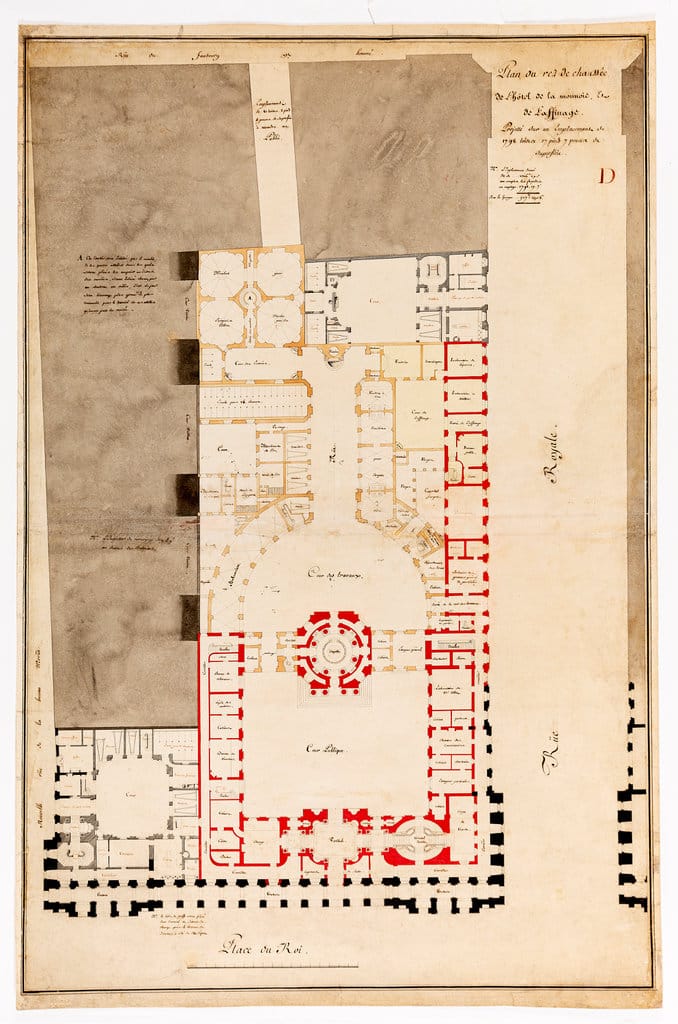

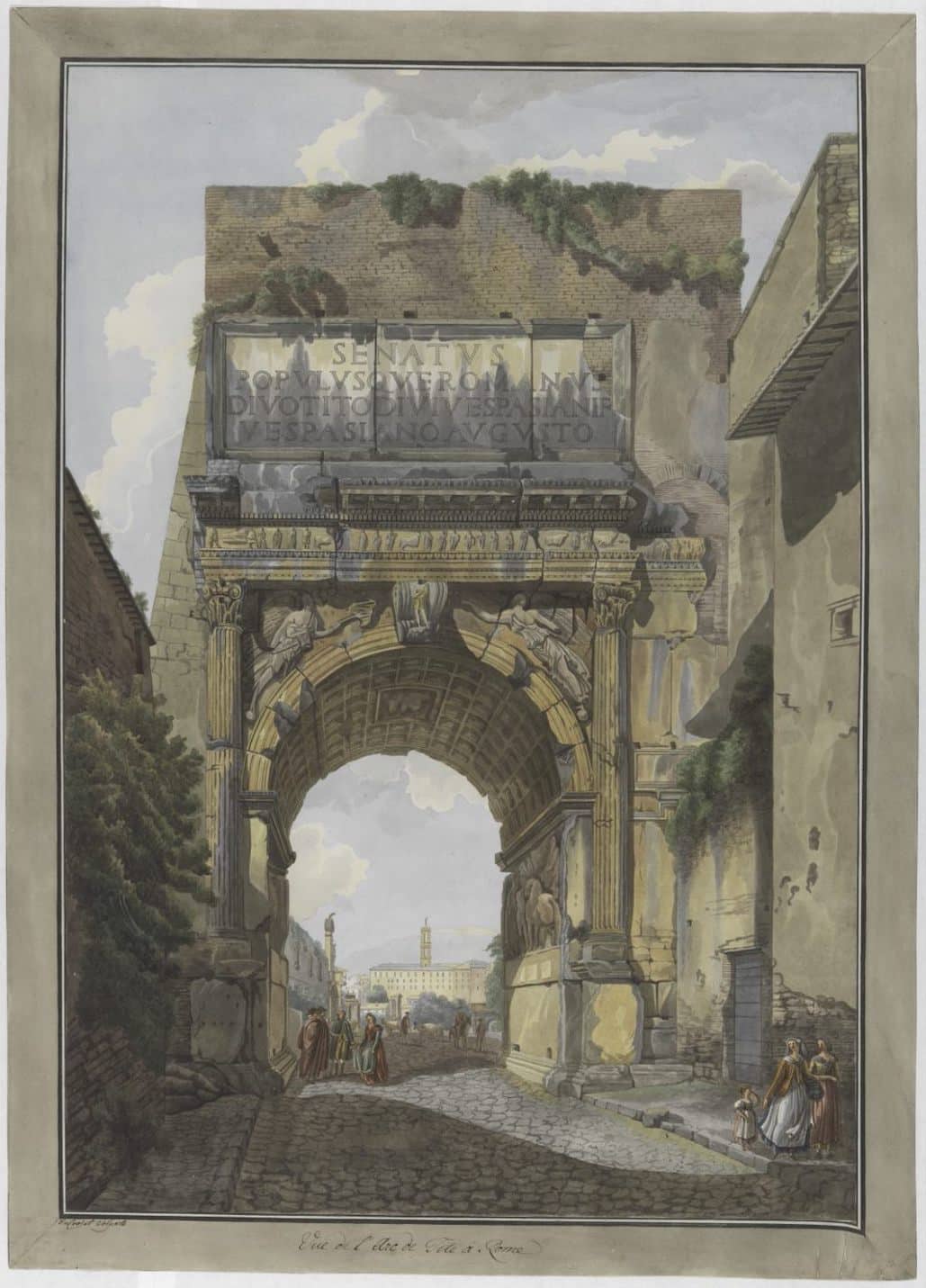

Under the title Inessential Colors, the Princeton art historian Basile Baudez traces the complicated history of colour in architectural drawing in a splendidly illustrated and deeply researched monograph. Taking us from an earlier story of ‘black and white’ through to a period in which real colours were ‘imitated’ in elevation and perspective, the author traces the emergence of colour conventions in the process of Enlightenment professionalization. He then concentrates on the transformation of these conventions to produce colours that were designed to ‘affect’ the emotions in the early period of Romanticism, from ruin pictures to elaborate perspectives, and thence, under the influence of the aesthetics of the Sublime, back to a monochromy that signaled a more sombre understanding of architecture and death in the age of the Revolutionary Terror. The book concludes with a detailed and extremely useful account of the draftsman’s tools, instruments, pigments, and paper, that sustained this extraordinary era of experimentation.

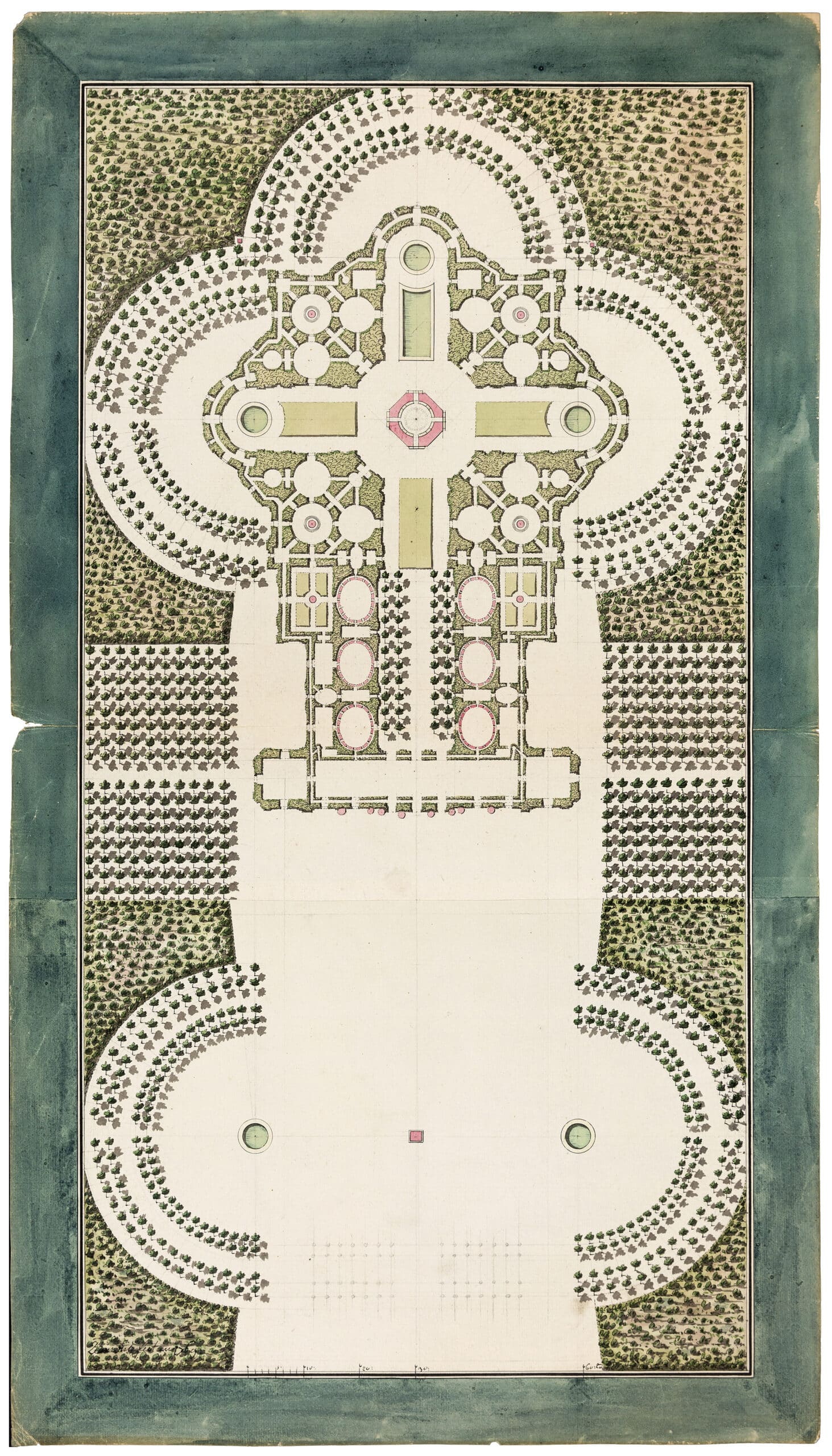

In the space of this brief appreciation, it is not possible to review all the treasures of archival discovery, intellectual and cultural interpretation, and the sheer beauty of the architectural drawings amassed. Perhaps the singular originality of the work consists in its expansion of the historical study of architectural representation, first to the powerful influence of cartography from the Renaissance to the map-making agencies of the Napoleonic regime, and second to the interrelationship between strictly technical drawings – sections, elevations and plans – and more topographical and perspectival representations. In a delightful and lapidary passage, Baudez points to the place of the map of Holland by Berkenrode and Blau as it appears on the wall of three of Vermeer’s paintings. Baudez further includes instances of garden design, topographical mapping, and military defenses in wide-ranging comparisons. Dramatic images of Charles de Wailly’s pulpit design from Saint-Sulpice are juxtaposed with the Revolutionary vision the centre of Lille transformed by François Verly as examples that were to animate the lively renderings of the late-eighteenth-century Grand Prix submissions. In both these instances, the translation of the use of colour from one regime to another became fundamentally important.

In concentrating so intently on this largely overlooked and understudied aspect of architectural history, Baudez has opened up a veritable pandora’s box of questions and future researches that will find in his meticulous account a fundamental reference and stimulus. Thus, while the general temporal and formal classification adopted to structure the monograph works to the benefit of a coherent narrative, the sheer chronological and geographical range of the examples opens up questions of difference according to cultural and intellectual context. These might be profitably mined in future studies, with the roles of diverse professional formations and training, in drawing schools, engraving shops, and architecture and engineering schools; here hinted at in the excellent section profiling Jean-Jacques Lequeu, not an architect, but trained solely as a draftsman in one of the many Ecoles gratuite de dessin that fed the printing, engineering, and architectural offices of the late eighteenth and early nineteen century – a resentful ‘Bartelby’ of drafting before the fact. For many of the architectural renderings of the modern period – as for those today – the question of authorship and even inventive practices has to be understood in the context of a skilled assistant workforce of draftsmen in the rapidly expanding architectural or engineering bureaucracies.

The extraordinary value of Baudez’s research and publication lies precisely in its vast range, the prolixity of its all-colour illustrations and archival references, that allow the reader to examine the evidence and parse the interpretations, and that opens up a historical examination of manual representation in an age when its overcoming by digital techniques has rendered it all but obsolete. The concentration on the idea and application of colour is especially salutary when the supplied colours of Silicon Valley provide unthinkingly dull and repetitive conventions unimagined by the experimenters of the early modern period. This work now takes its rightful place beside the more traditional histories of representation: of perspective from Erwin Panofsky to Hubert Damish, of composition from Colin Rowe to Jacques Lucan, of the axonometric from Auguste Choisy to Yve Alain Bois. A place, rather like the small clues investigated by micro-historians like Carlo Ginzburg, that takes an apparently ‘marginal’ subject and finds it in expansion to be a central motor of perception and media construction.

Basile Baudez, Inessential Colors: Architecture on Paper in Early Modern Europe (2021) is published by Princeton University Press. Copies of the publication can be purchased here.

Anthony Vidler is Professor of Architecture at the Cooper Union.