Keshi Ghat

Seeing is a reaching out, a kind of metaphorical touching that involves one’s whole being and is reciprocal.

Amita Singh

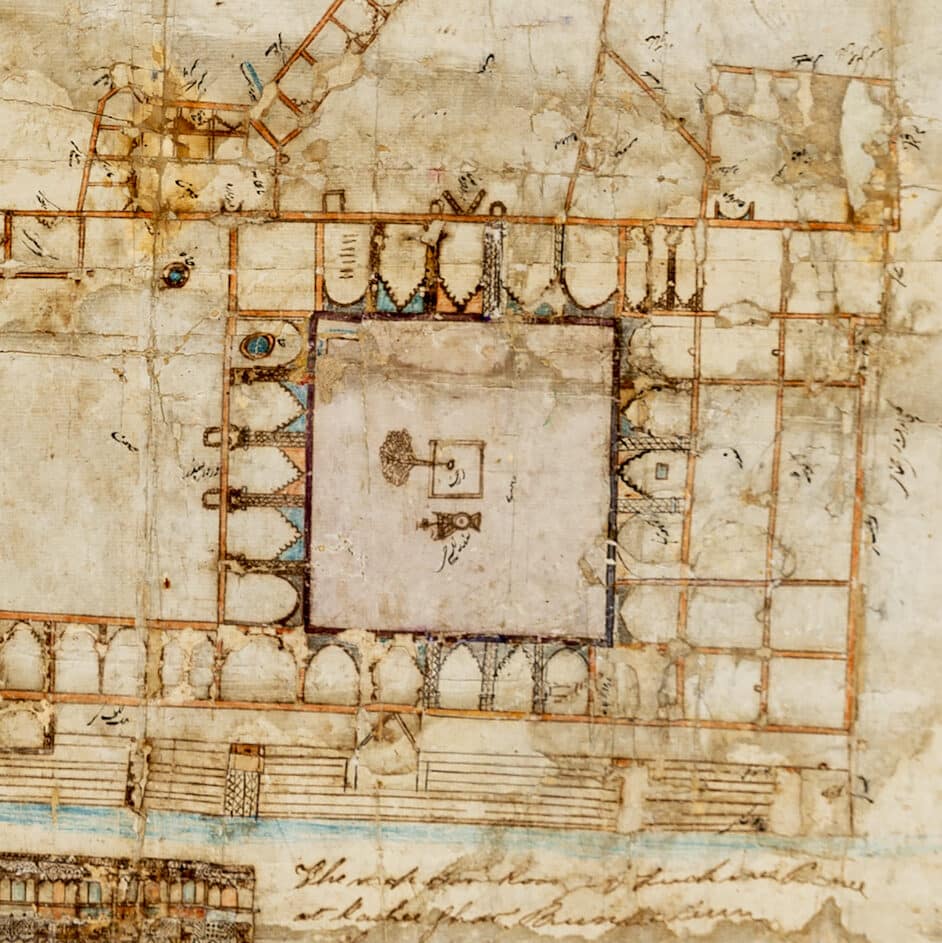

If you hadn’t read the title of the drawing, you would have probably guessed that this would have been a riverfront mosque in India. I did too. The courtyards reminding me of the vast expanse in the centre of a mosque, while the Arabic writing affirms this assumption. Until, I tell you that this is in fact, a public bath on the riverfront of the sacred Hindu city of Vrindavan.

This is Keshi Ghat. Keshi Ghat is the location where the Hindu deity Lord Krishna killed the monster Keshi; who had attacked said deity, many moons ago.

What strikes as peculiar is the way the plan and elevations have been imagined. The drawings are of a public bath central to the Ghat, with an interior courtyard flanked by what are assumed to be bathing rooms. There is a kind of palimpsestic duality about the plan. Traditionally, a plan is a two-dimensional drawing, a slice of a section on a typical XZ plane.

However, this plan represents spatial notions such as the central courtyard, the Ghat (the steps), and the river Yamuna (shaded in blue). But the arches corresponding to the columns all make it seem like a montage of plans and elevations.

Such contortions of the cartesian system are not uncommon in traditional miniatures of the region. Braj miniatures, especially those influenced by the Mughals, often depicted complex perspectives. Showing three-dimensional scenes on a two-dimensional medium, erasing any sense of cartesian space.

You see the trefoil and cinquefoil arches flattened and placed as if they to narrate what the space offers, visually. This is in conjecture to the schematic elevation already provided at the bottom of the paper, but it makes us truly look into the interior space. The elevation halts the viewer and demands them to stop seeking beyond. But the contorted plan invites, nay, lures, the viewer to read, and be read by the architecture it represents.

Amrutha Viswanath is currently studying architecture in Chennai, India.

This text was entered into the 2020 Drawing Matter Writing Prize. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the prize judges.