Mies van der Rohe: Clarity as the Aim

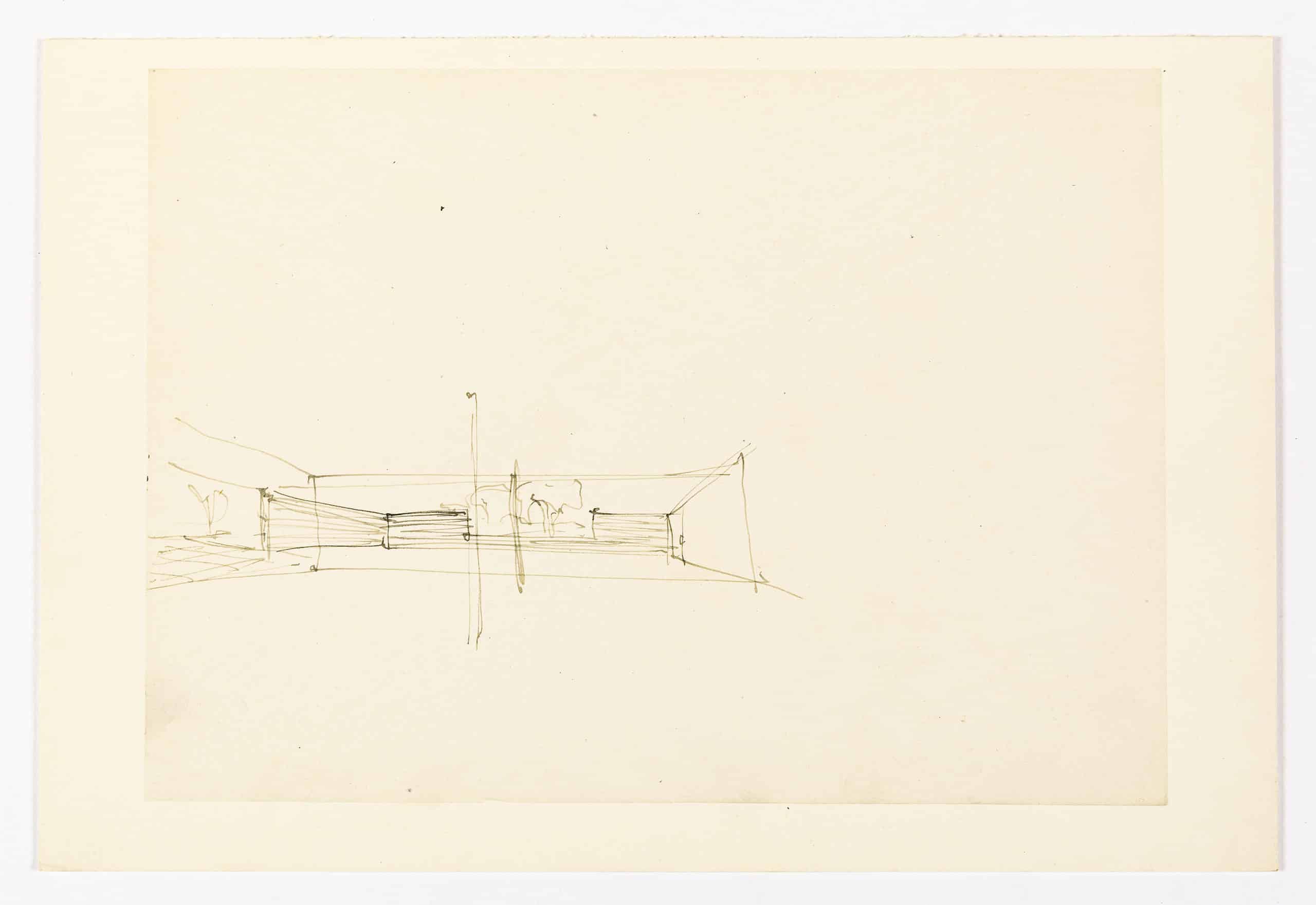

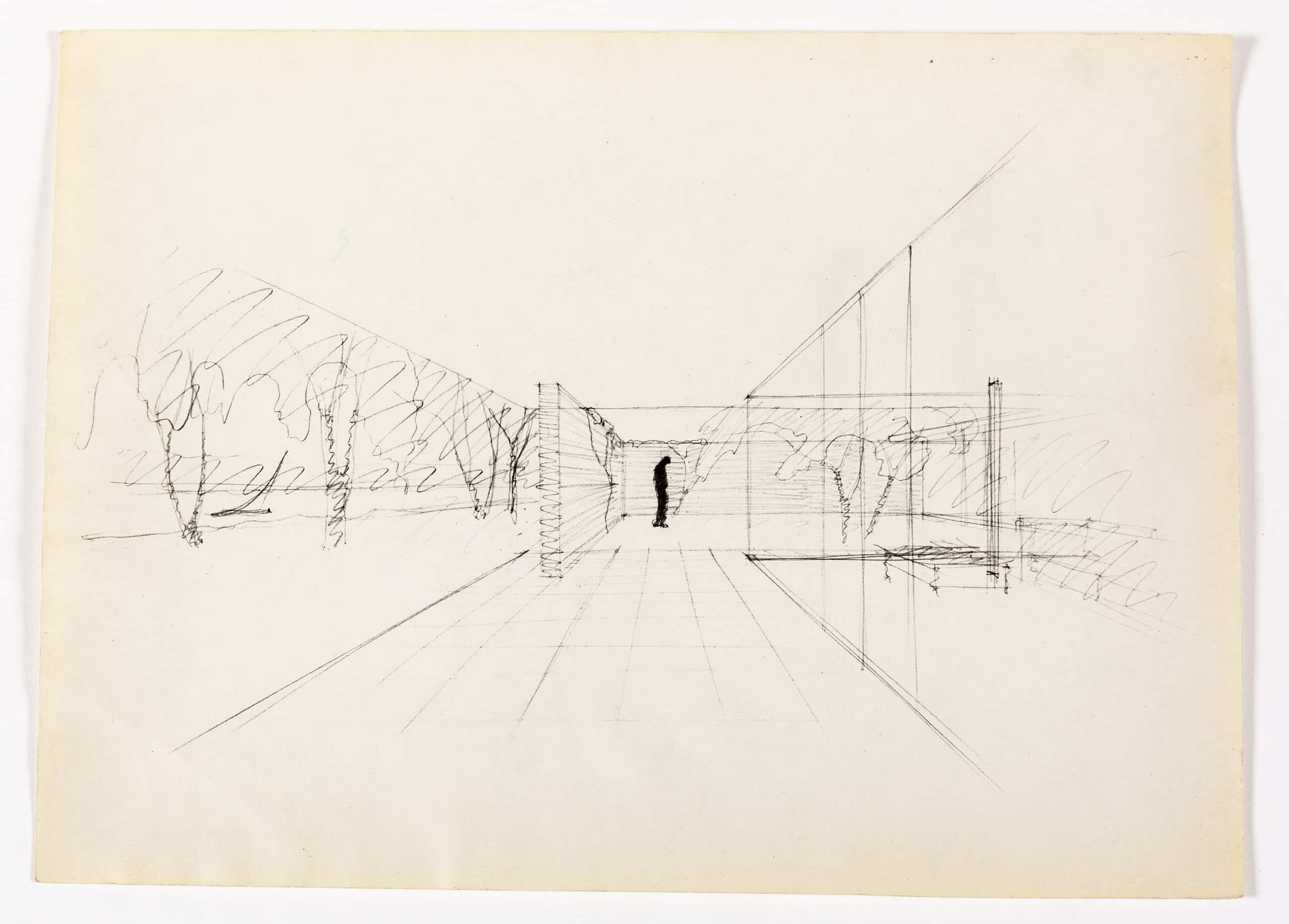

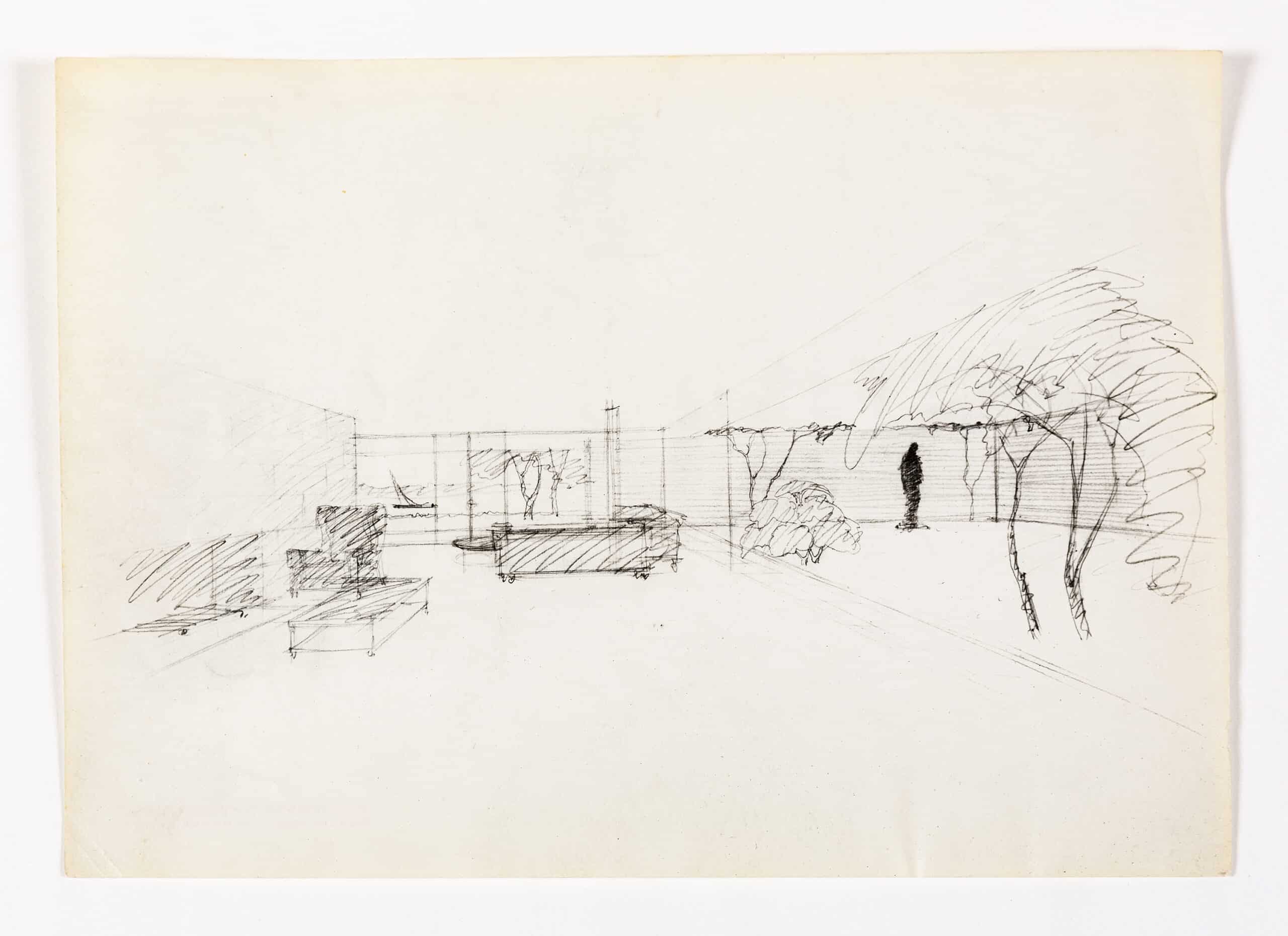

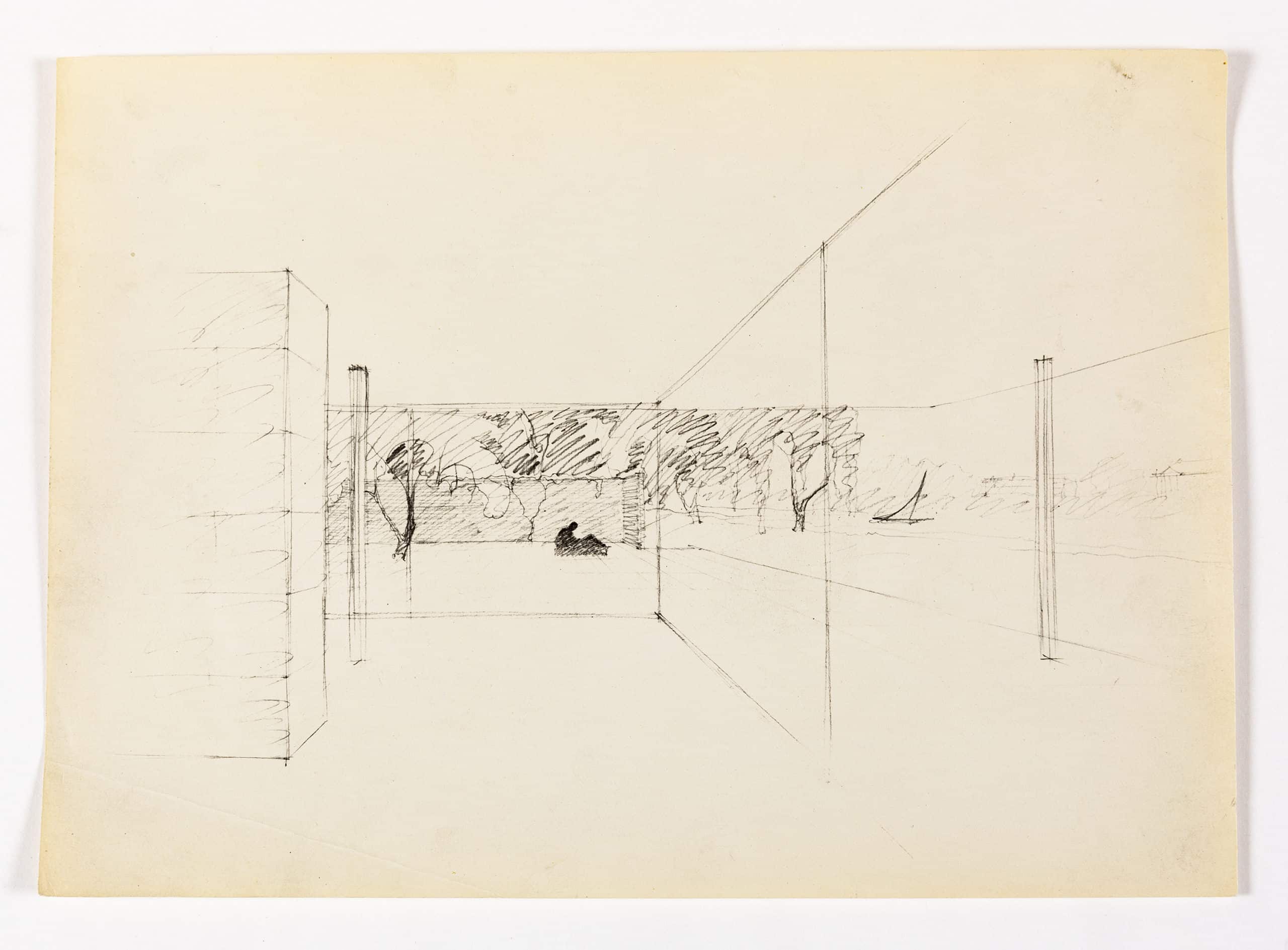

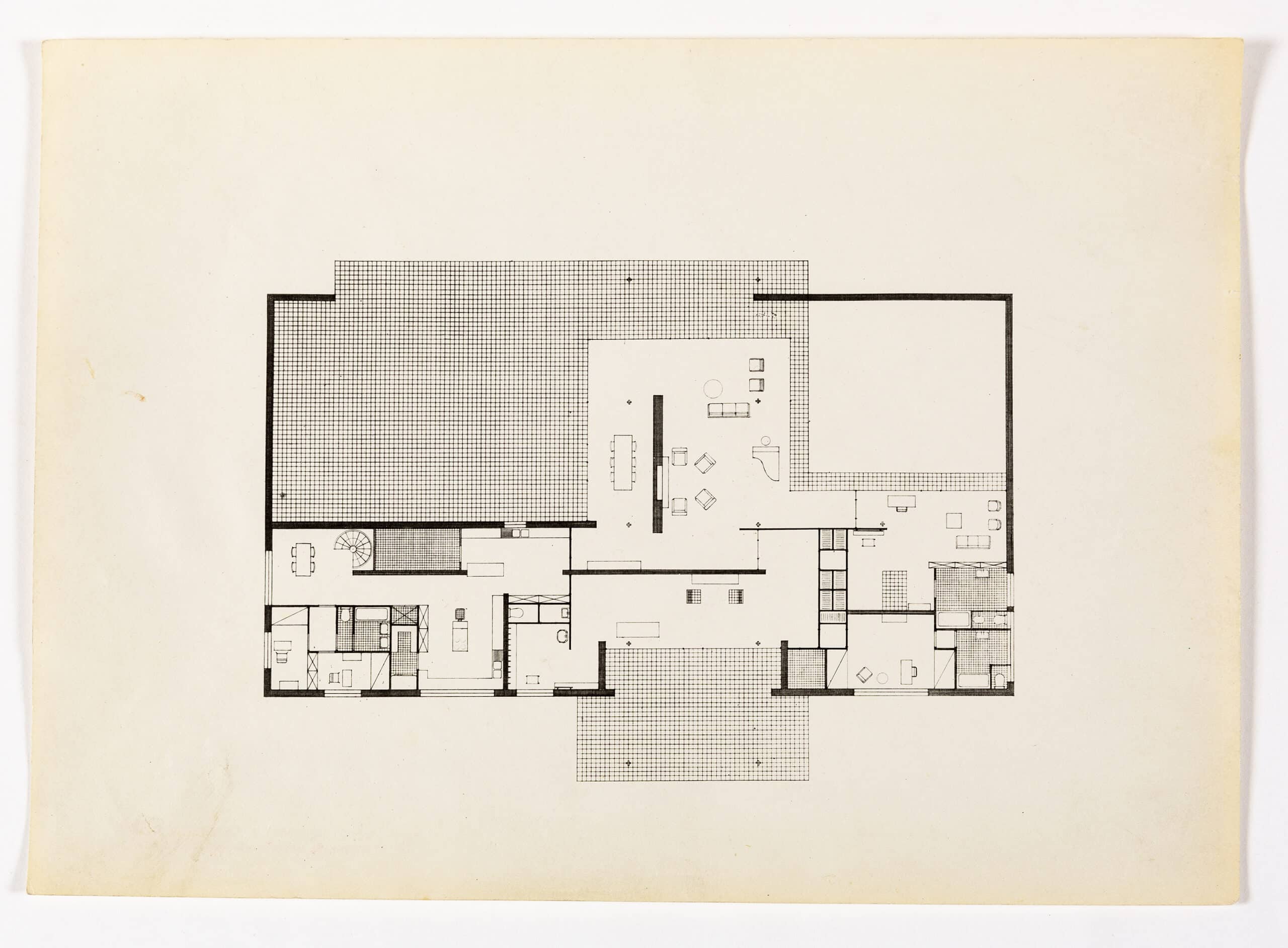

Mies’s work is an exemplary embodiment of the idea of architectural abstraction. His buildings are free of all the ‘figurative’ ingredients that characterise traditional architecture. They are made up of materials or constructive elements given cohesion and structure by a series of visual devices.

But, although his language is so far removed from that of tradition, Mies is one of the contemporary architects most closely linked to the spirit of the great monuments of Antiquity. His approach to historical examples is based on a gaze with untold powers of abstraction, capable of ridding architecture of all its specific, contingent aspects to elevate it to the status of pure formal construction. The abstract process is precisely what enables him to situate the works of the past on the plane of his interests and concerns as a modern architect, thus allowing him to dialogue with them, to reveal their present.

Mies observes reality and extracts the materials for his architecture from it. The products of industrialisation and technical progress are a substantial part of this reality. Mies does not contradict them, nor does he overlook them: he takes them as they are, collects them and subjects them to a process of stylisation, before presenting them and creating a distance between them, thus generating a void. This is how he frees them from their previous conditioning and turns them into receptacles for values. This is the basic operation Mies carries out: the elements may be neutral, even anodyne, but their placement, their relationships and their distance lead them to embody values and foster an interpretation of the world. He talked about these issues in a 1930 lecture:

‘The new time is a fact; it exists whether we say yes or no to it. But it is neither better nor worse than any other time. It is a pure given […]. What is decisive is only how we assert ourselves toward these givens. It is here that the spiritual problems begin. What matters is not the what but only the how. That we produce goods and the means by which we produce them says nothing spiritually. Whether we build high or flat, with steel or with glass, says nothing as to the value of this way of building […]. But it is exactly this question of values that is decisive.’ [1]

This reflection puts Mies in a position to overcome the positivist, mechanistic burden that sometimes restricts the scope of modern architecture.

By declaring that form is not the immediate aim of the architect’s work, but rather the result, Mies seems to be warning us that striving to achieve beauty can often move us further away from it. Hence his appreciation for engineering works, for works that emerge from the solution of technical problems and not from the application of aesthetic apriorisms. Mies undoubtedly aspires to achieve beauty. But instead of setting out directly to find it, he tries to capture it with more elusive procedures, like those used by hunters waiting for their prey. For Mies, the work’s clear constructive expression, the precision of syntactic rules, and the sharp intelligibility of formal operations are, in fact, no more than a series of strategies which he entrusts with the mission of bringing about a beautiful form, so that, like in the famous Biblical parable, it comes as an extra.

Mies’s architecture is often associated with the concept of simplicity. It may be laconic and concise, but it cannot be considered simple. The simple may have the virtue of immediacy, but it expires on its own. Meanwhile, Mies’s works, rather than wearing away over time, become increasingly fascinating the more they are contemplated and studied. ‘Simple’ is not a word to describe an architecture that, after so many years of life, continues to stir up new ideas and act as a reference point.

At this juncture, it is helpful to make the distinction between the simple and the elementary. Simple things are made of one piece: they have no ingredients, and therefore no composition. Elementary things, meanwhile, emerge from the composition of elements in accordance with certain rules. These two terms should be compared to another two that are also used erroneously as synonyms: ‘complicated’ and ‘complex’. The complicated has nothing to do with the complex.

Furthermore, ‘complicated’ is the opposite of ‘simple’, but ‘elementary’ is not the opposite of ‘complex’; the elementary is the necessary condition for the complex to exist. Simplicity and complication are two opposite poles, but neither of the two gives the object aesthetic value, while elementariness and complexity make up a complementary conceptual pair of capital importance in the artistic process. Works of art are always complex constructions in which their constituent elements are recognised. Only through intelligent management of the elementary can we achieve the complex.

This becomes clear through analysis of Mies’s works. His essential aim is clarity. They are not at all complicated but they are strikingly complex, as their elements coordinate and interweave without blending into one another, maintaining their identity and recognisability throughout the process. In one of his final pieces of writing, Mies declared the following:

‘[…] I believe that the building art has nothing or little to do to do with the invention of interesting forms or personal predispositions. True building art is always objective and expresses the inner structure of our epoch out of which it arises.’ [2]

For Mies, admitting the objective nature of architecture equates to accepting that the elements reality provides are the raw material for the artistic task. The world is a given. It does not need to be invented, just recognised and given a stable, comprehensible form. ‘This world and no other is offered to us. Here we must take our stand’. [3]

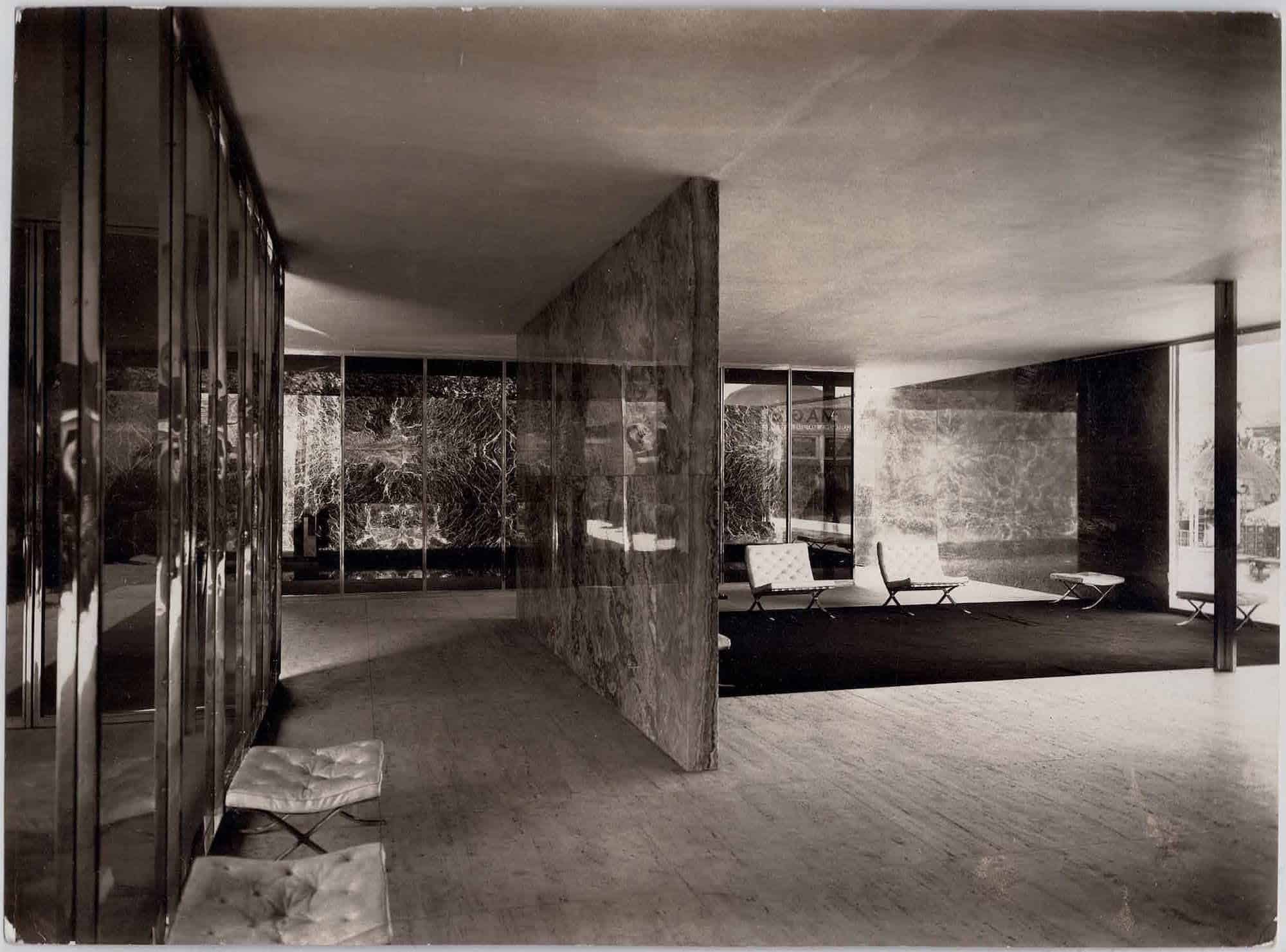

But, despite this commitment to objectivity, his architecture, as indicated by Ernesto Rogers, has ended up being one of the most lyrical around. [4] This is not a contradiction: Mies works with ‘objective’, somehow untouched materials, until he extracts their most hidden registers; he uproots them from their everyday context to place them on another stage, where they become an object for contemplation. This contemplative attitude is one of the key aspects of his architecture.

For works to become objects for contemplation, they must possess the property of transparency; the beholder’s gaze must cross through them, rather than stopping on them, thus going beyond the physical limit defined by them. Understood in this way, transparency contrasts not just with opacity and impenetrability, but also with excess of form and the rhetoric of meaning: in other words, with all that tends to obscure and block the achievement of that crystalline, open, bright dimension that constitutes the basic requirement for contemplation. Transparency can therefore be likened to some forms of silence. Silence can also be transparent or transitive and can make the creation project itself into other dimensions of reality that are not strictly contained in it.

Mies’s architecture abounds with effects of literal transparency, but its true aim is to achieve conceptual transparency: that unique condition in which, paradoxically, clarity and enigma overlap. Faced with Farnsworth House, Crown Hall, the Seagram Building or the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, to name just a few of Mies’s main projects, one experiences an unusual feeling of disruption and suspension of time, as though witnessing a silent revelation. This explains the nature of the search for the essential Mies claims as the motto for his work. Work based on omission, on renunciation, guided unwaveringly by the principle of spiritual economy, which dictates that one must always be ready to get rid of anything that does not pass the test of necessity. Only this way—Mies seems to whisper—is it possible to aspire to the epiphany of the transcendent. Perhaps this is the deep meaning of the aphorism ‘less is more’.

Carlos Martí Arís was an architect and full professor at the Departamento de Proyectos Arquitectónicos of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC).

Notes

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, ‘The New Time’, in Fritz Neumeyer, The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994), 309.

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, ‘Building Art of Our Time’, The Artless Word, 336.

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, ‘Miscellaneous–Notes to Lectures’, The Artless Word, 328.

- E.N. Rogers, Experienca de la Arquitectura [Esperienza dell’architettura] (Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión Ed., 1960).

Excerpted, with publisher’s permission, from Carlos Martí Arís, Eloquent Silences — Writings on Art and Architecture (Marseille: Éditions Cosa Mentale, 2020), 79-82. The book is available for purchase here.

– George Dodds