Next Year in Yemen

‘Next year, there will be a civil war in Yemen. Please lend me the money so I can go now,’ I had the wit to ask my parents. It was after my first year in architecture school, not knowing that this journey would come to define me as an architect.

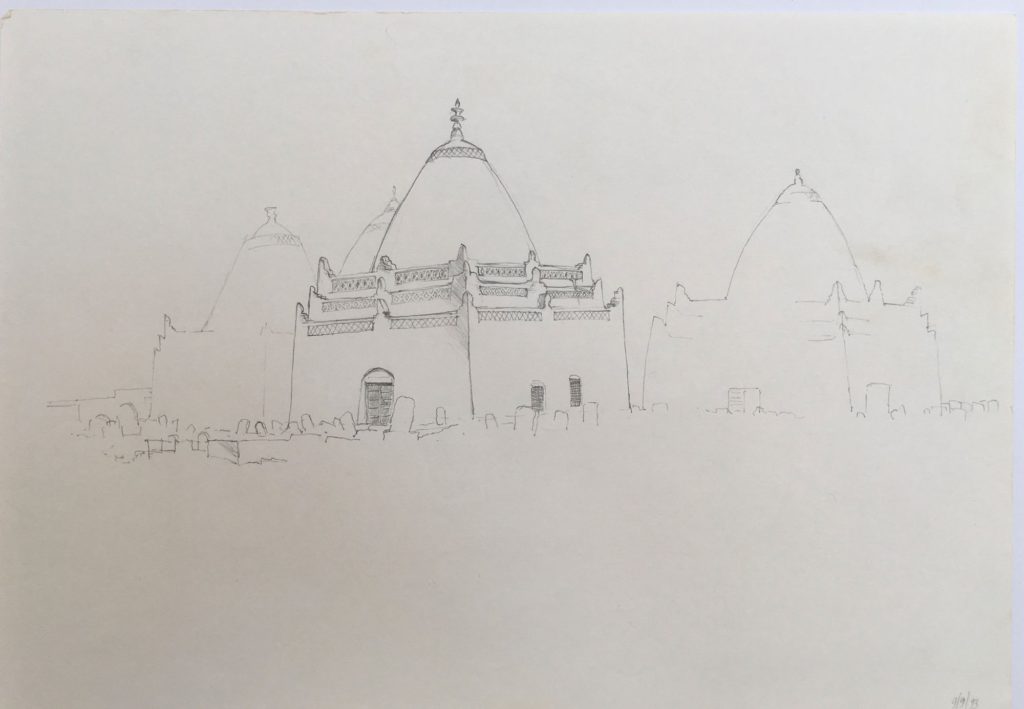

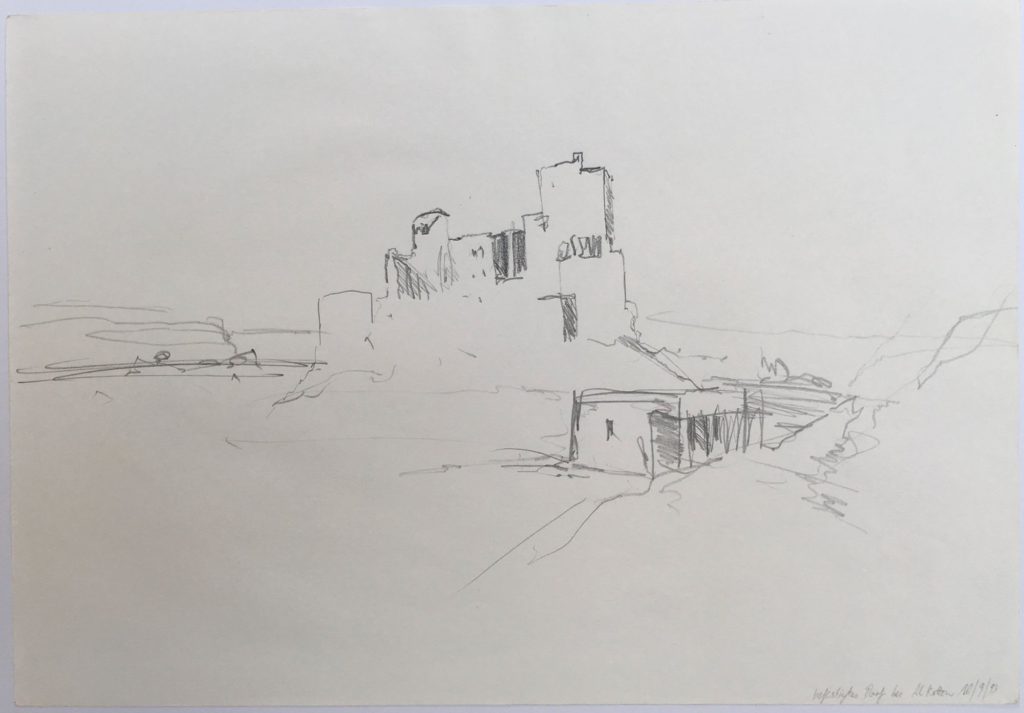

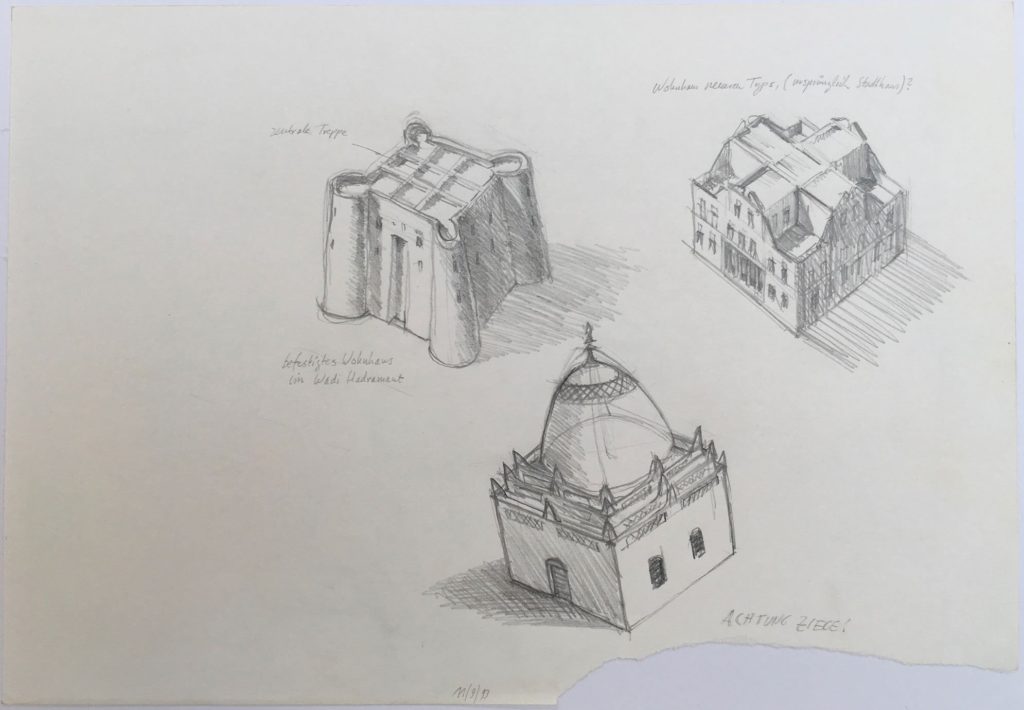

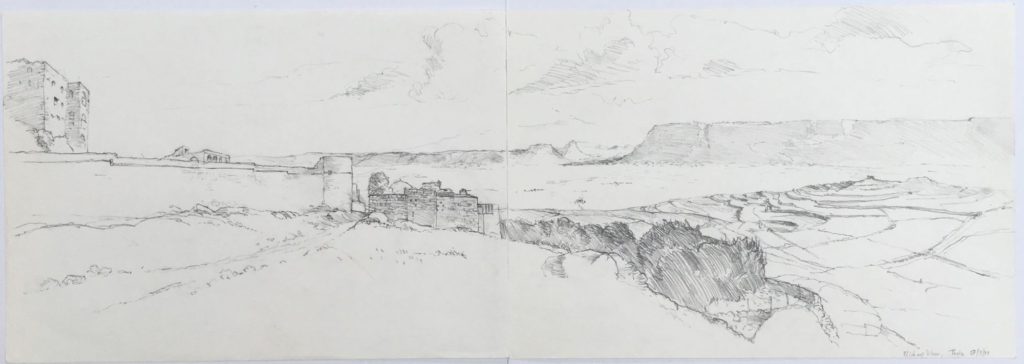

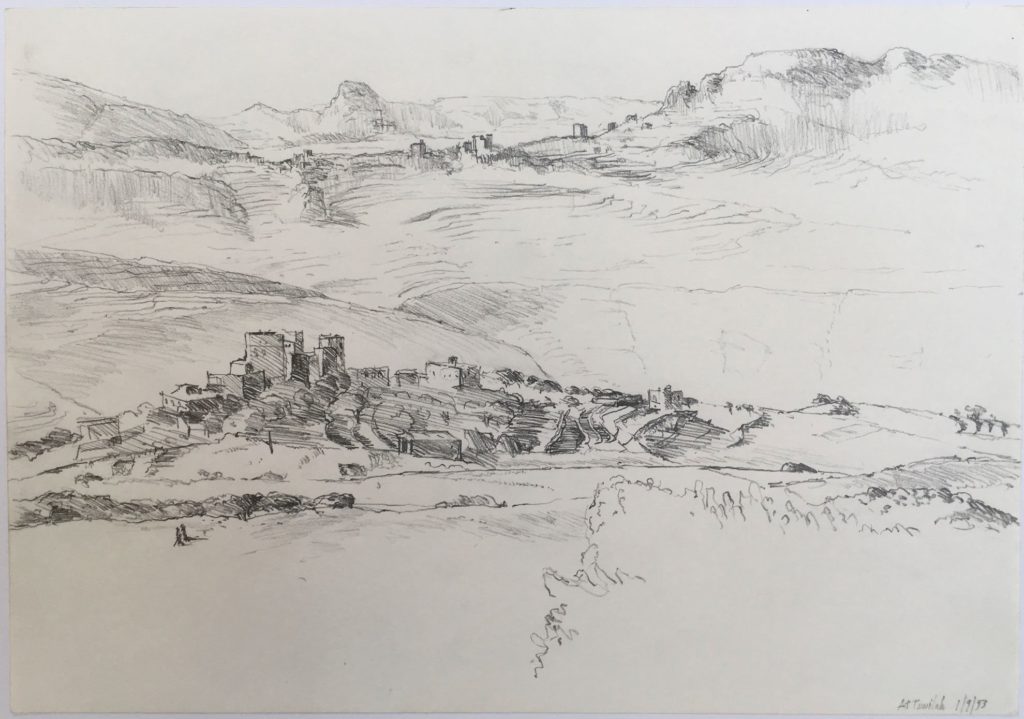

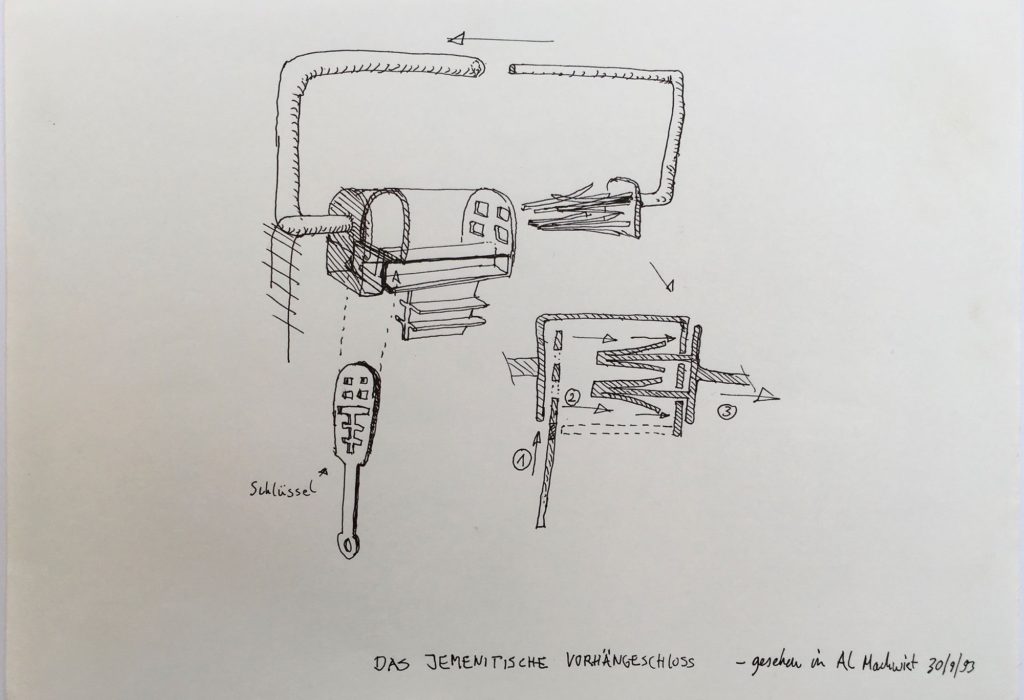

Our journey had a sleepwalker’s quality that only naive 22-year-olds can experience. My travel companion, Holger Sulitze, and I had just arrived in Sana’a when we met an aristocratic Italian man who resided in a palace in the old city. His father had been the personal doctor to the last sultan of Yemen in the 1960s. Somehow he decided we could be useful for him in promoting tourism, and he provided us with a jeep and a driver to cross the desert to reach the Queen of Sheeba’s Marib and beyond, the great city of Shibam in the Wadi Hadramaut. From there, we stumbled, literally, from one magical place to the next on a journey that took us to the coast, the green hills of Arabia Felix, and to the mountains in the rugged north.

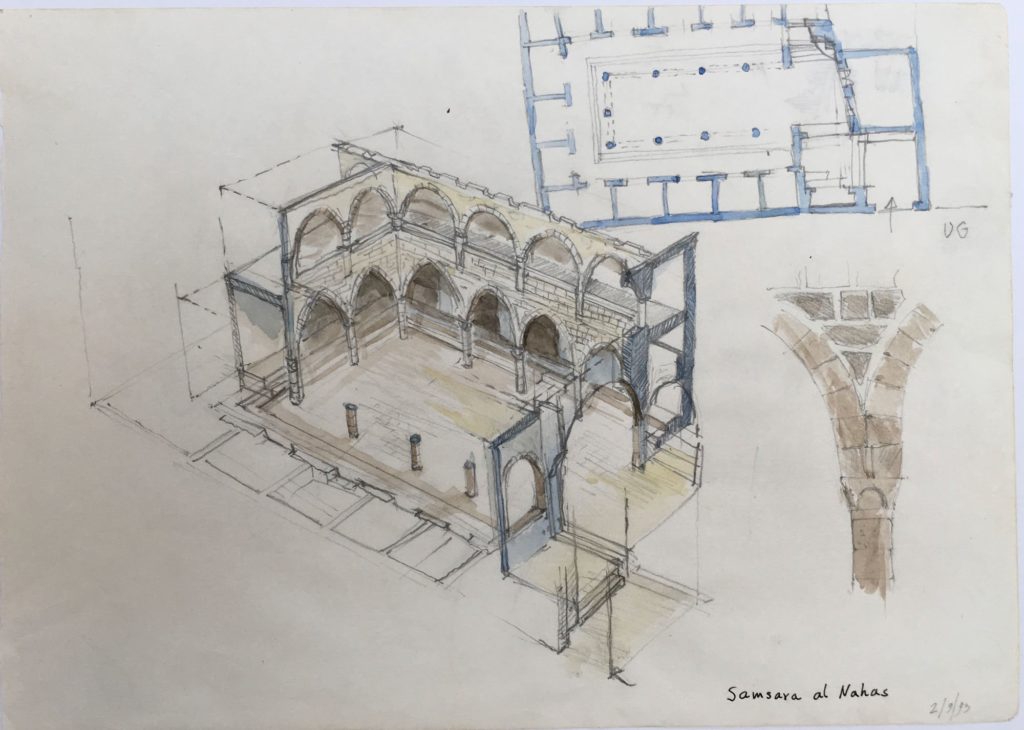

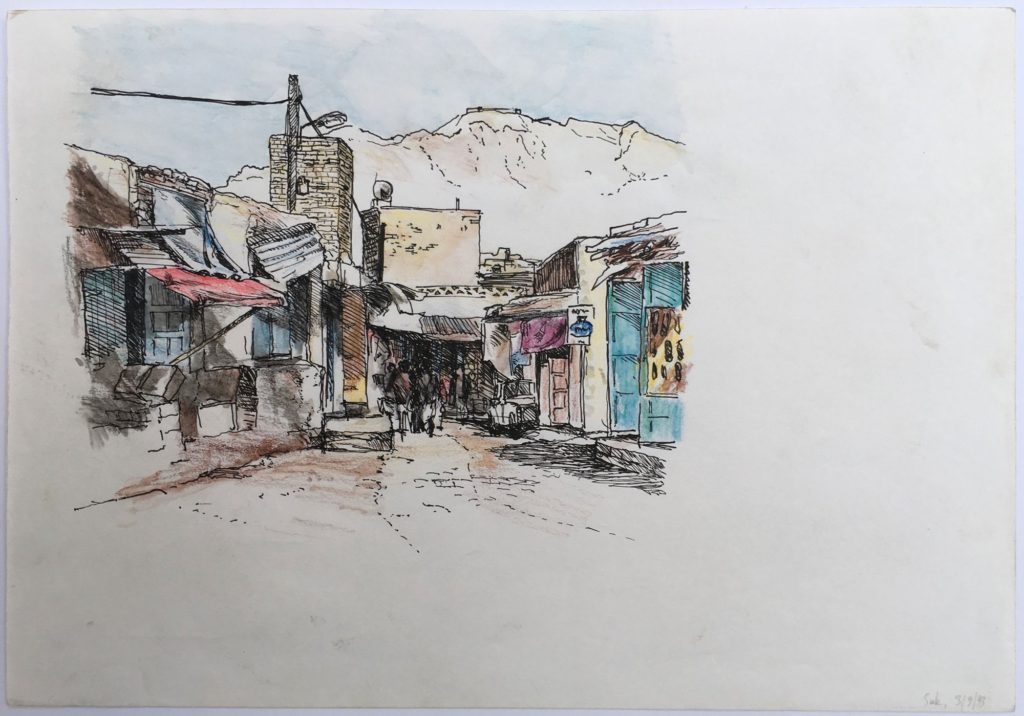

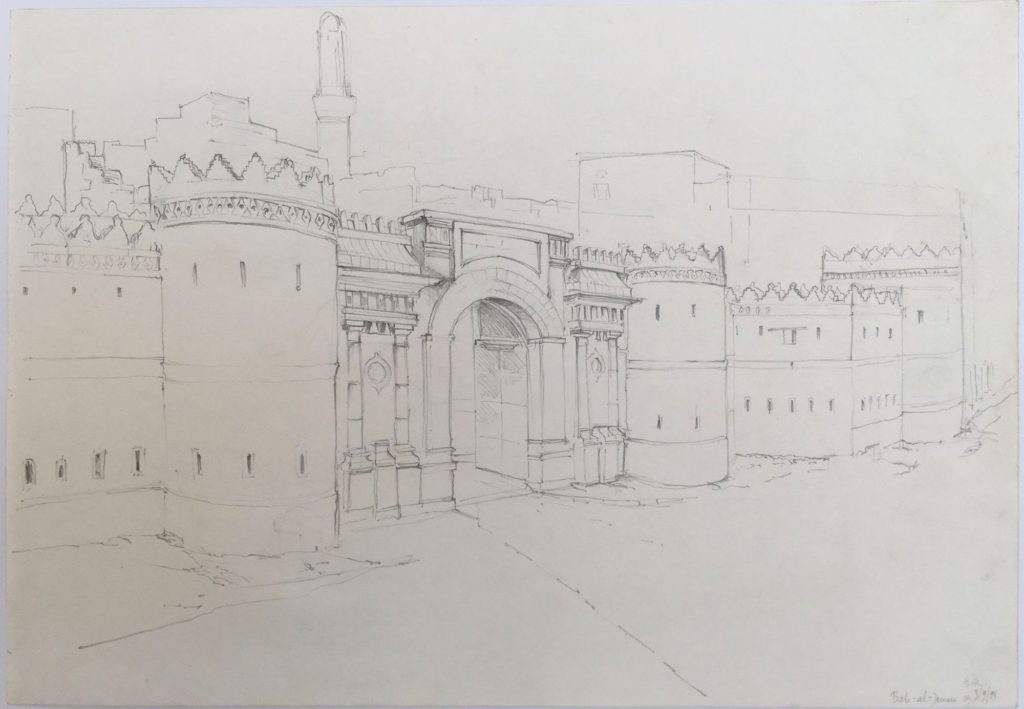

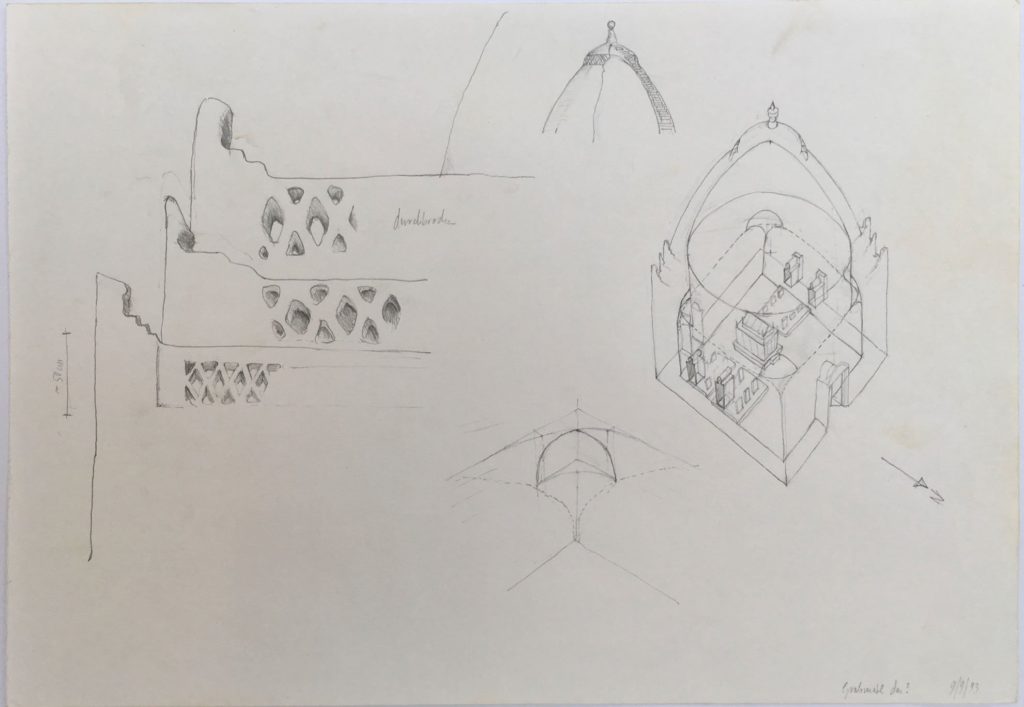

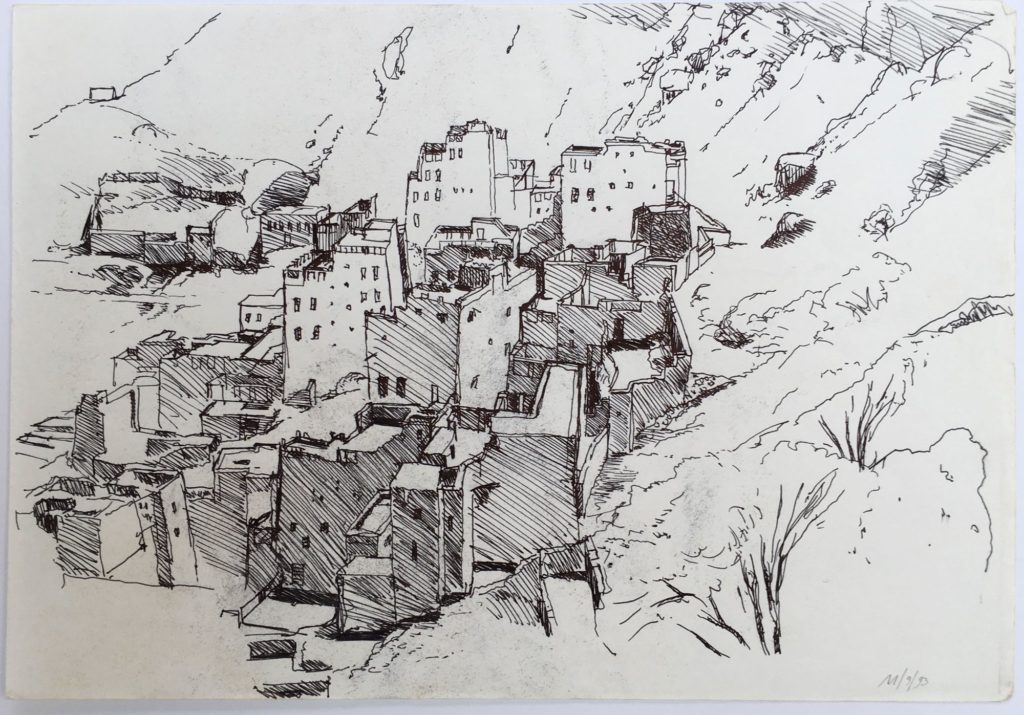

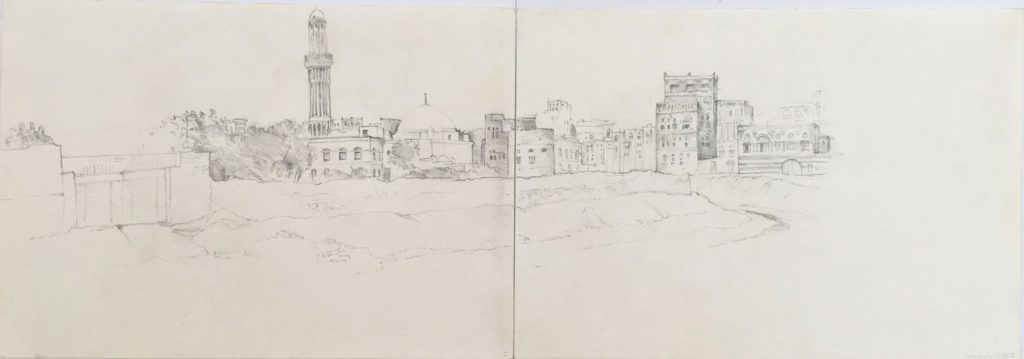

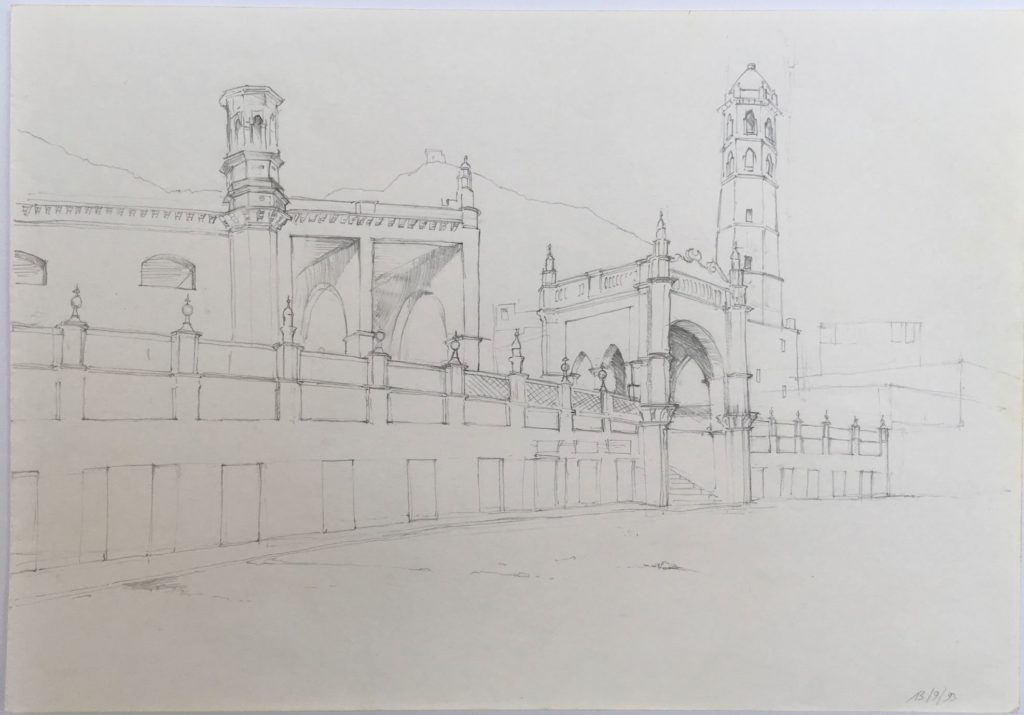

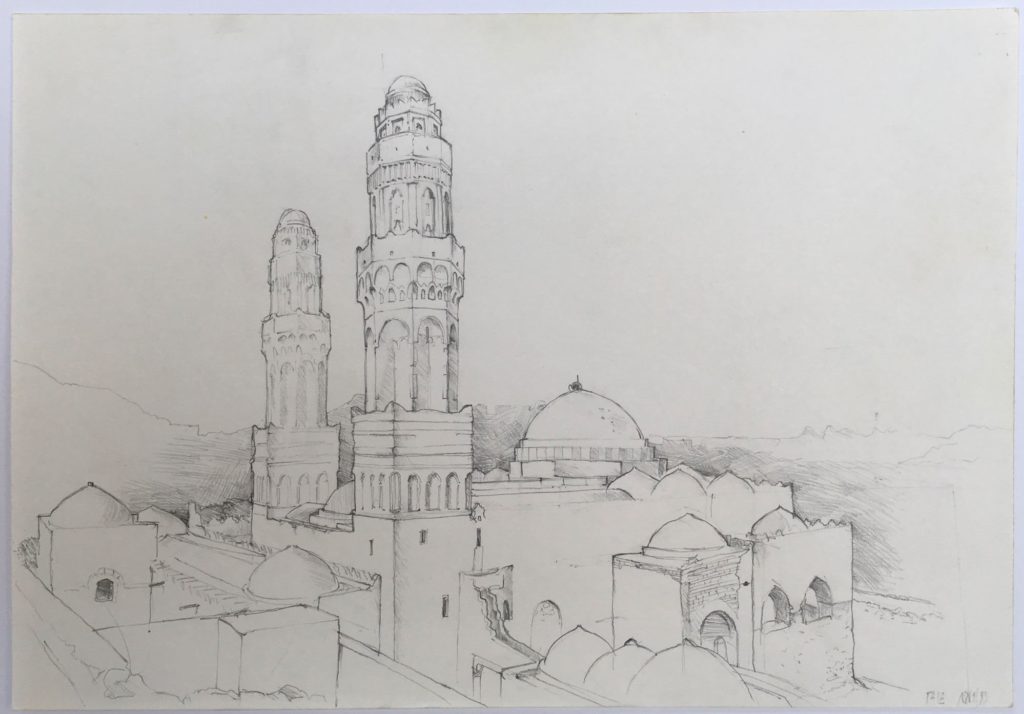

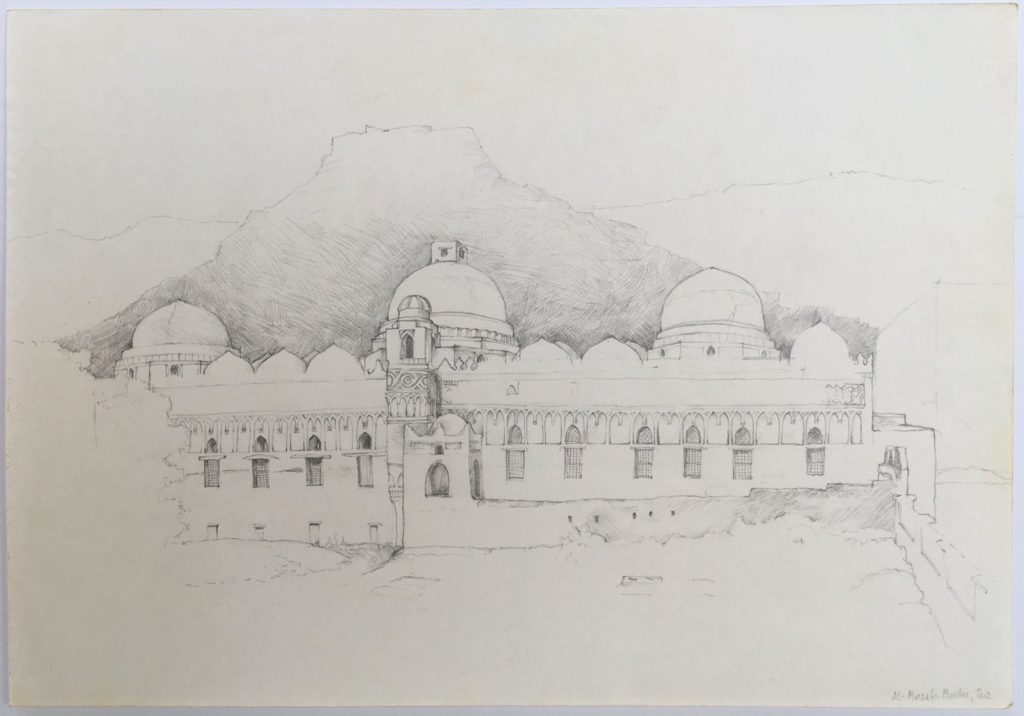

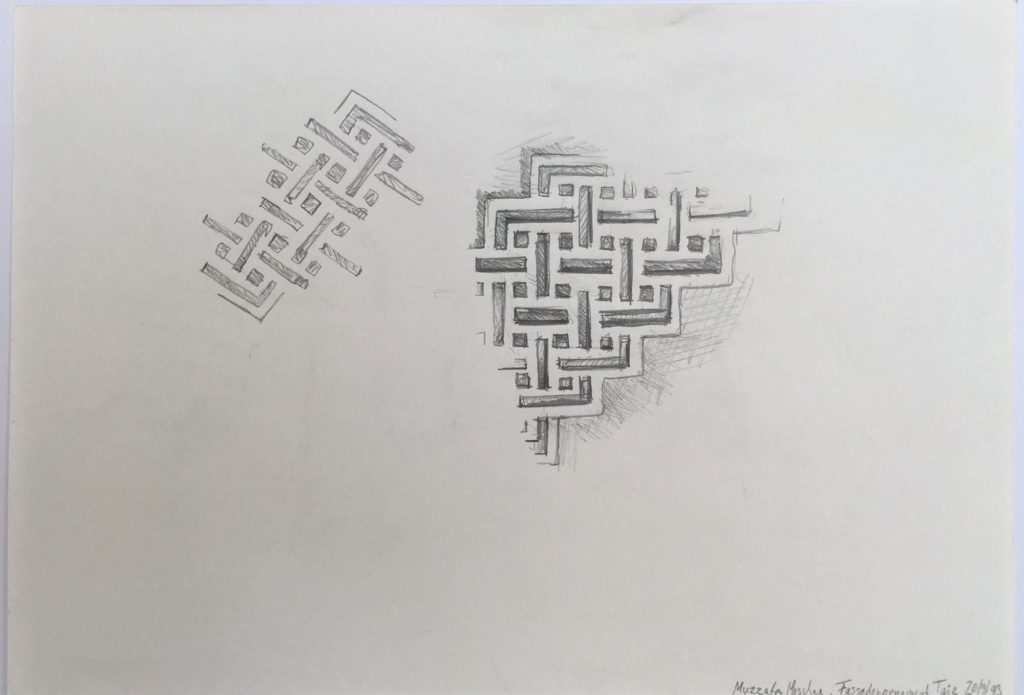

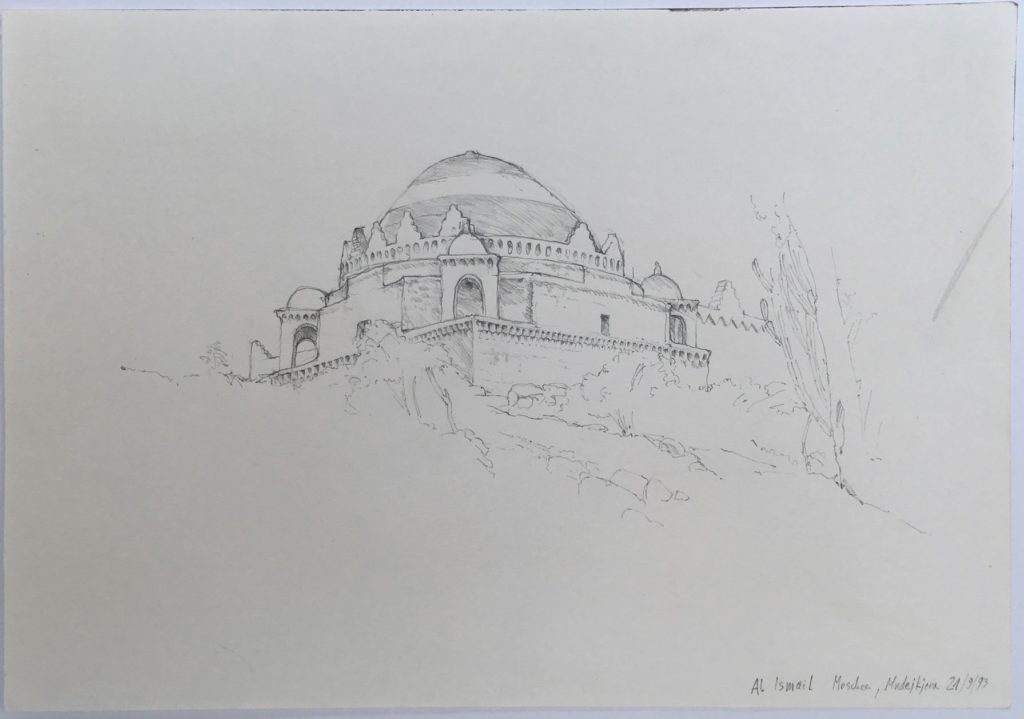

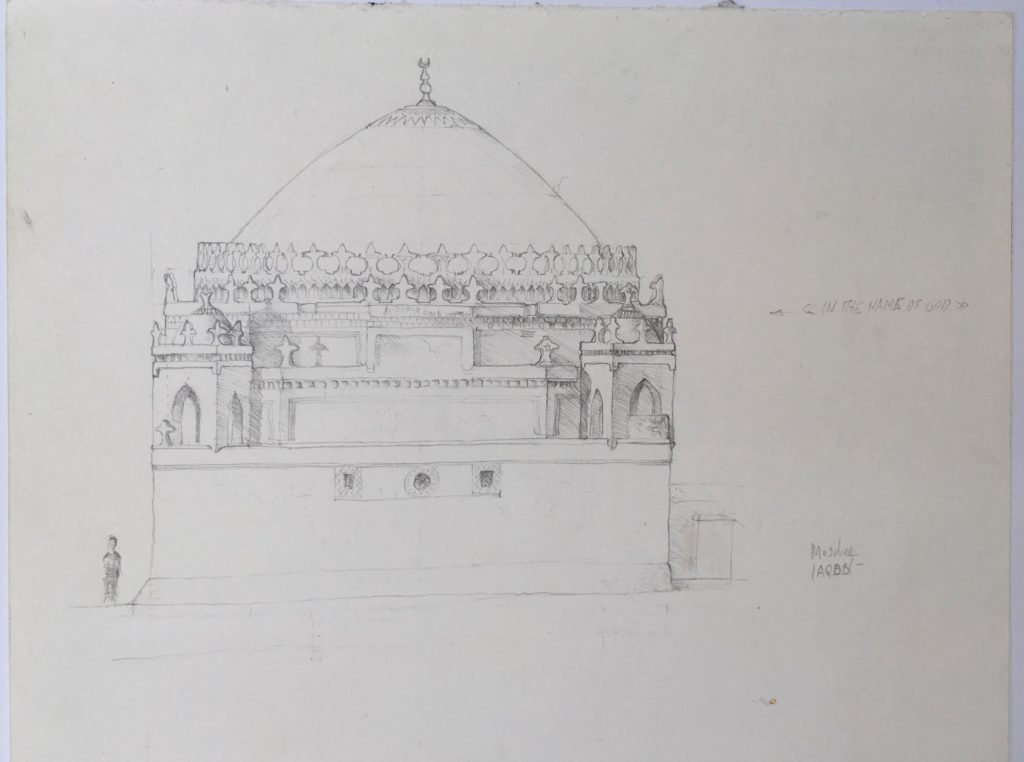

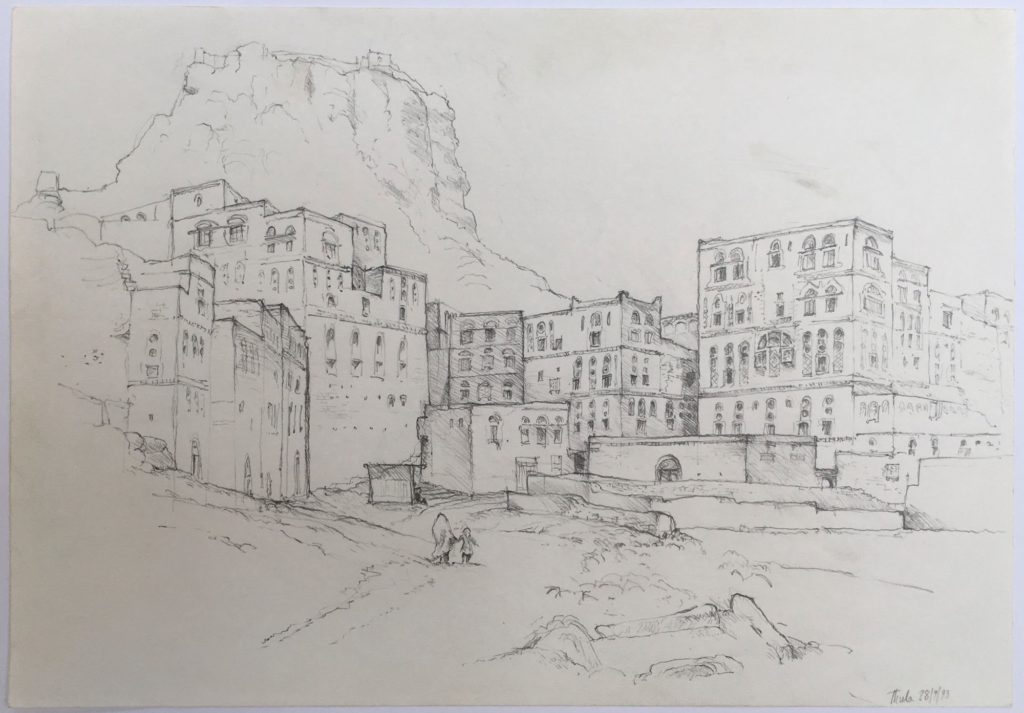

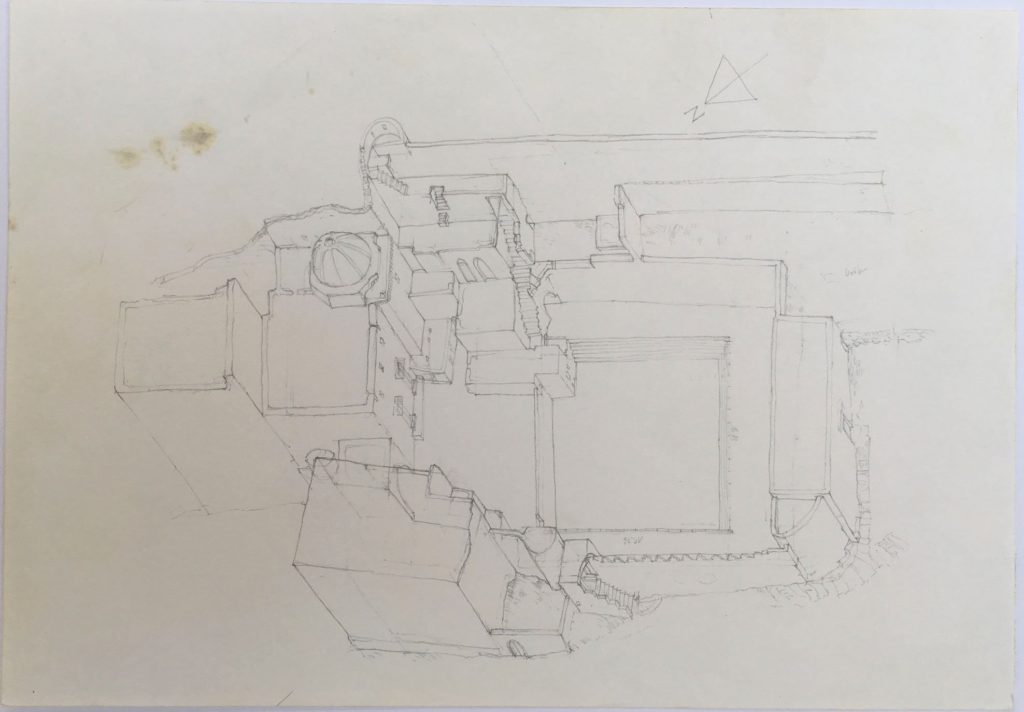

I was mesmerised by the seemingly natural unity of culture and architecture. I already knew that I loved walls, but the Yemeni architecture opened my eyes to the beauty of mass, plasticity and typological richness.

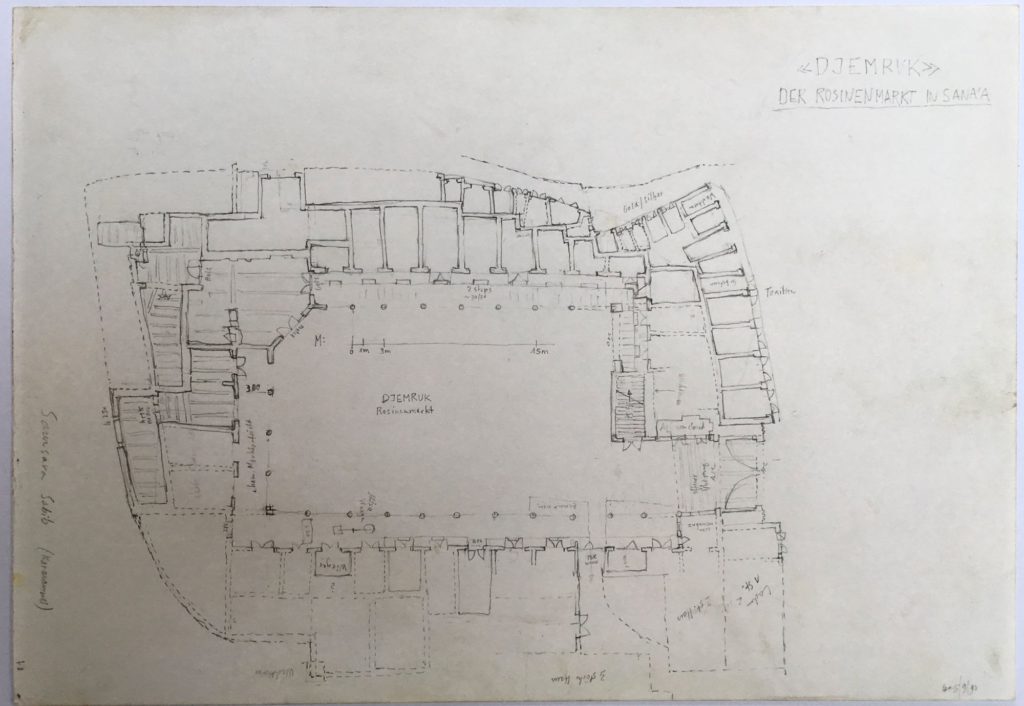

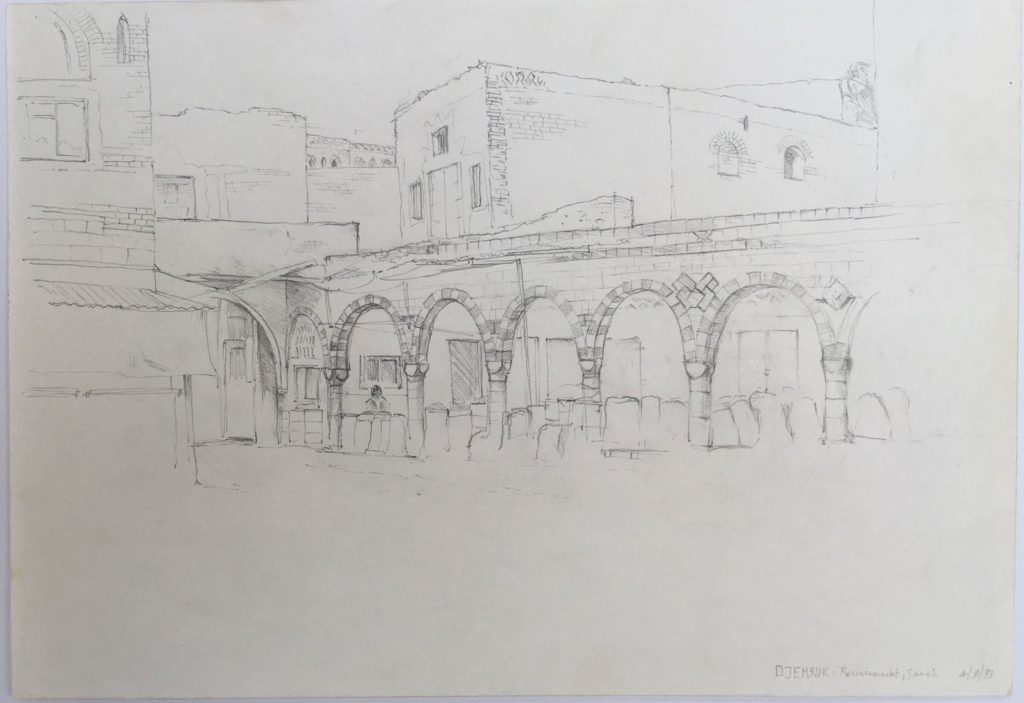

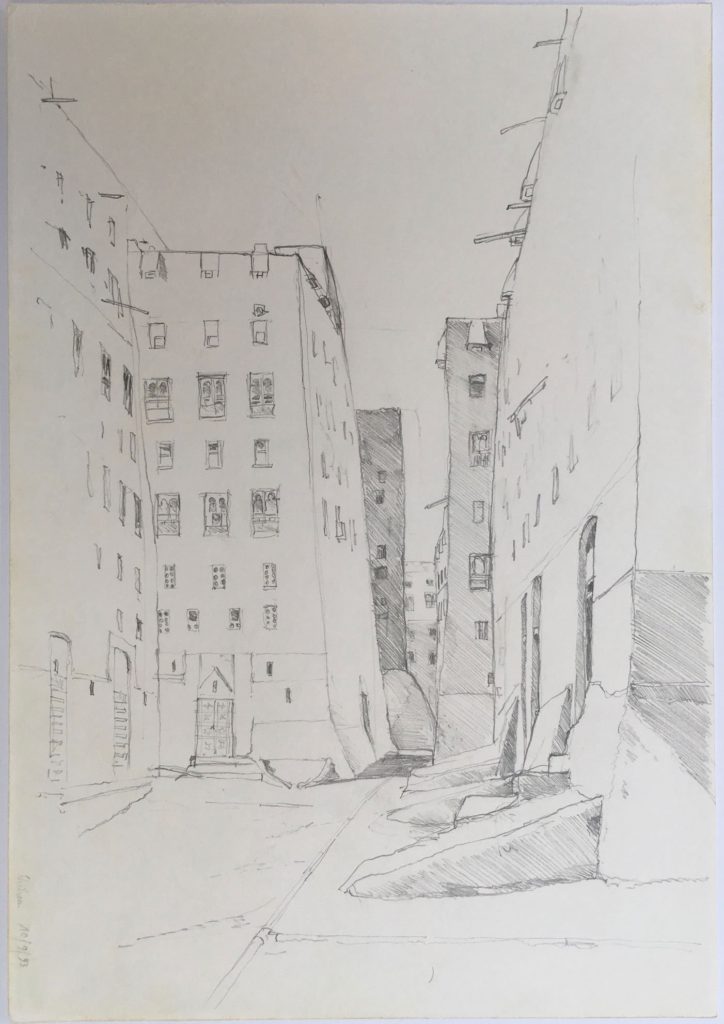

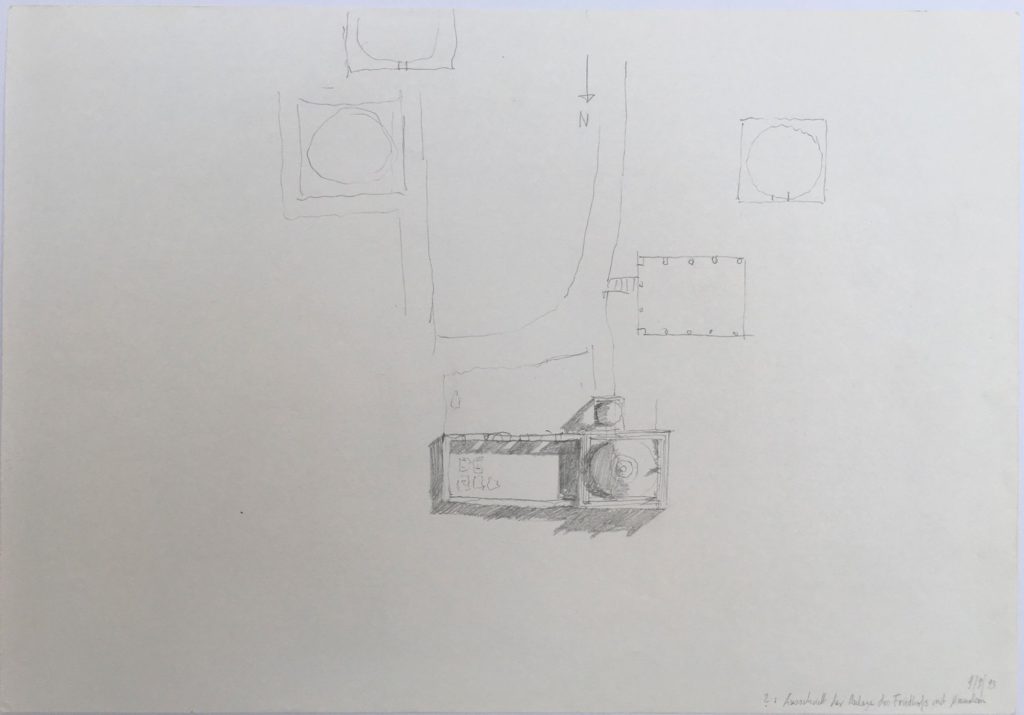

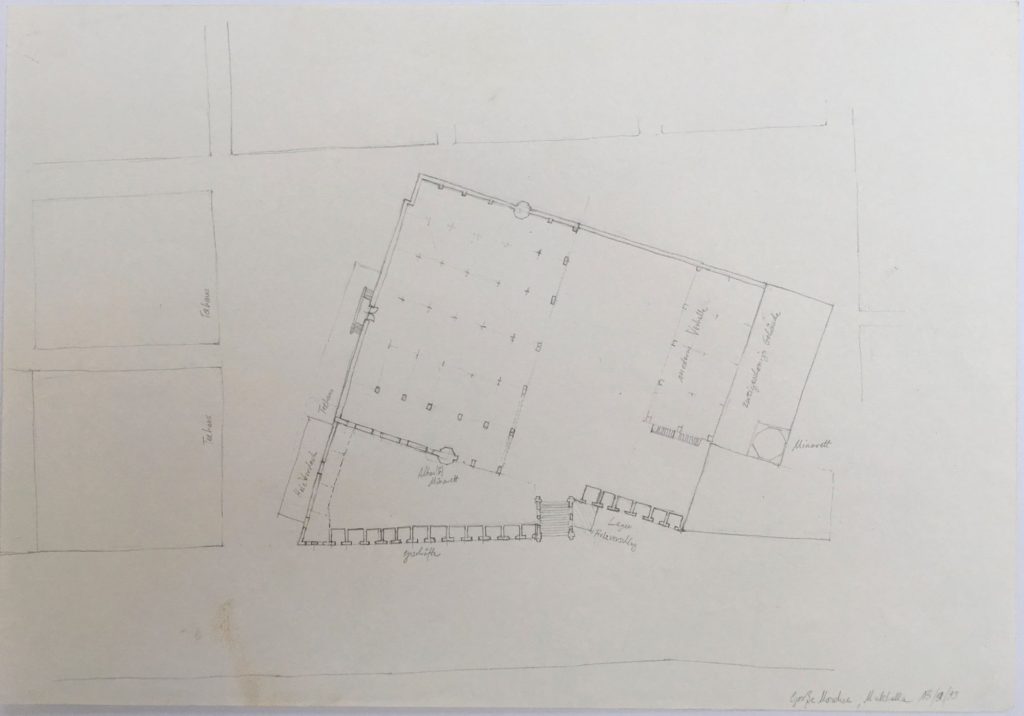

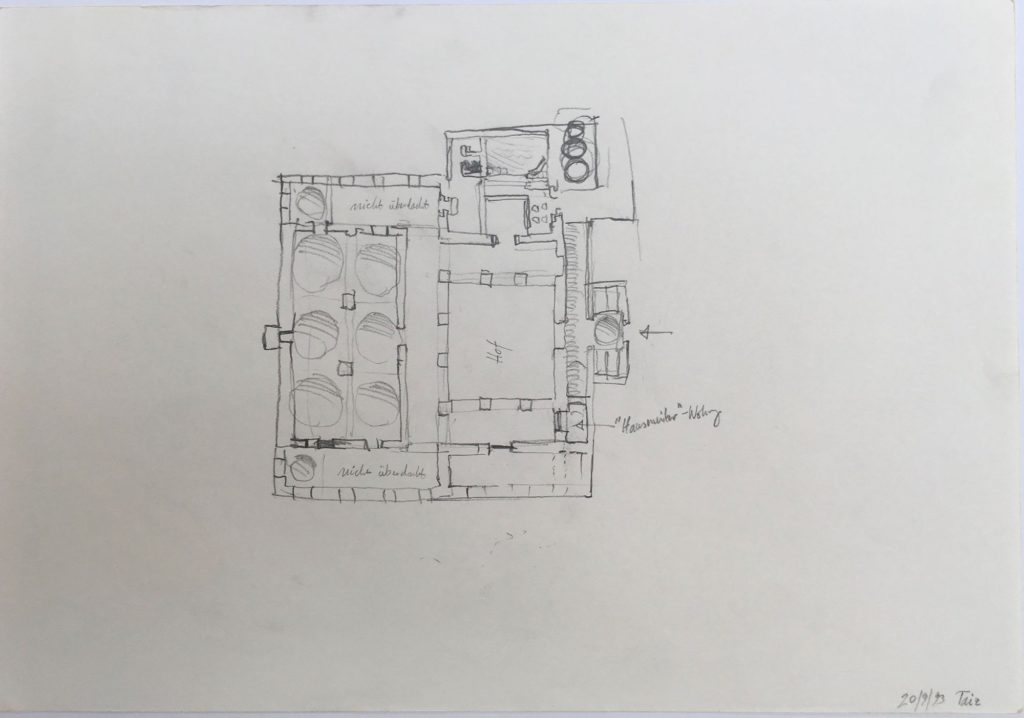

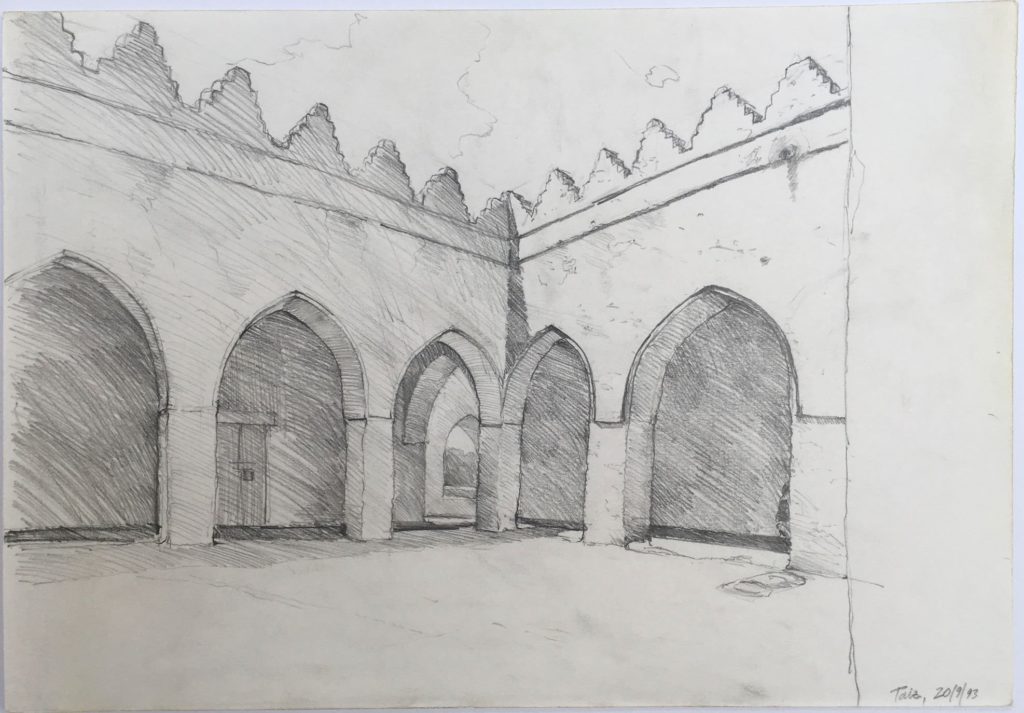

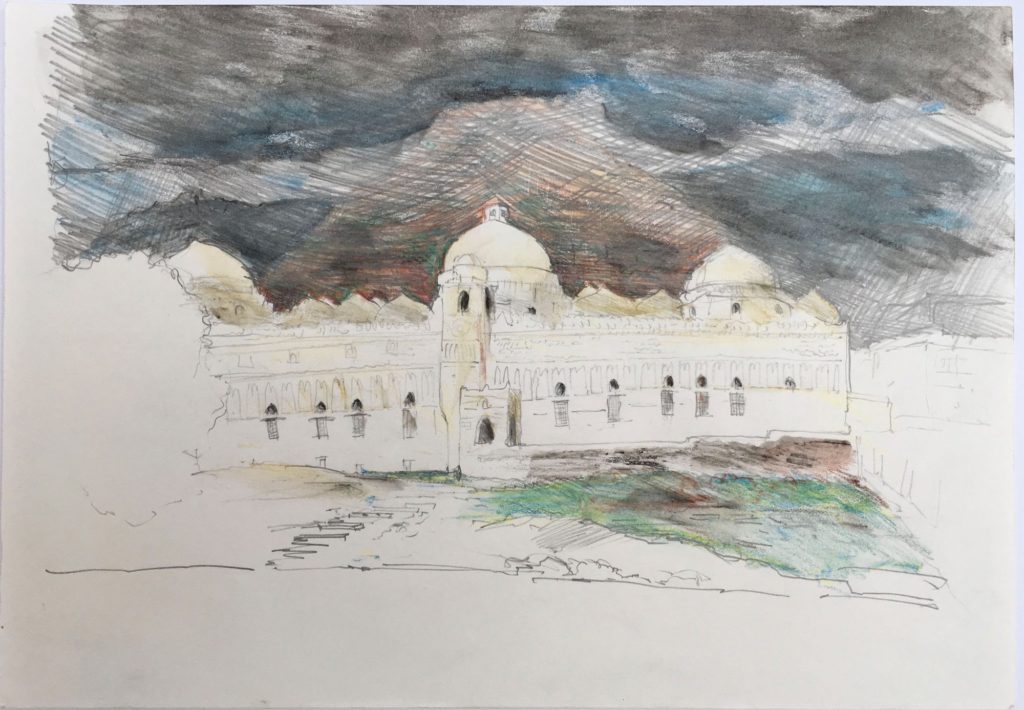

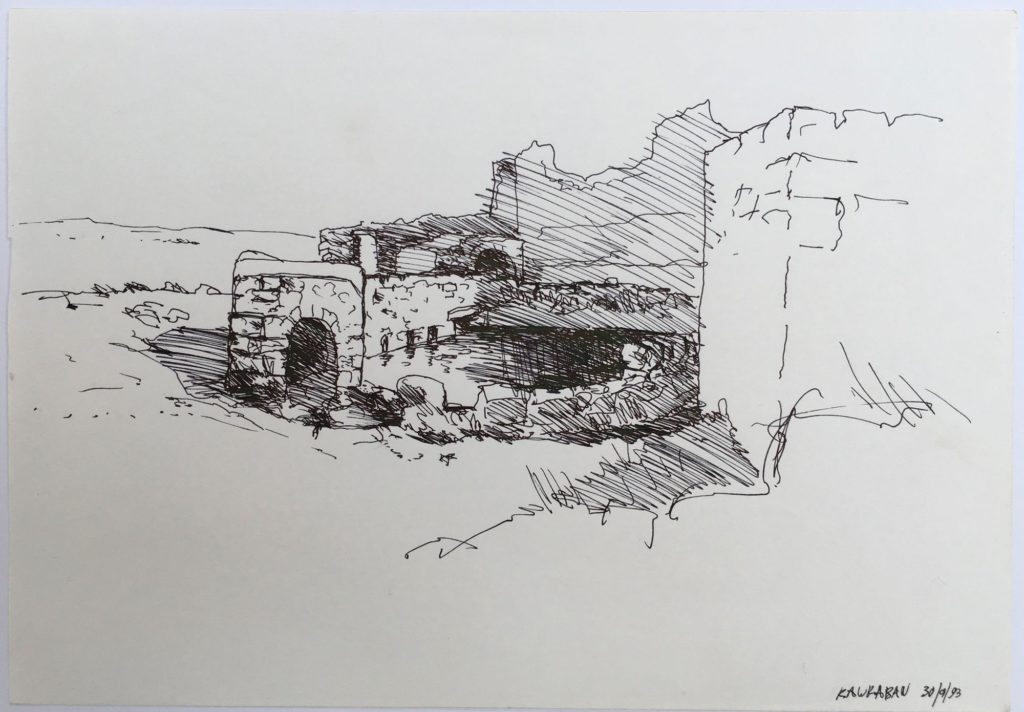

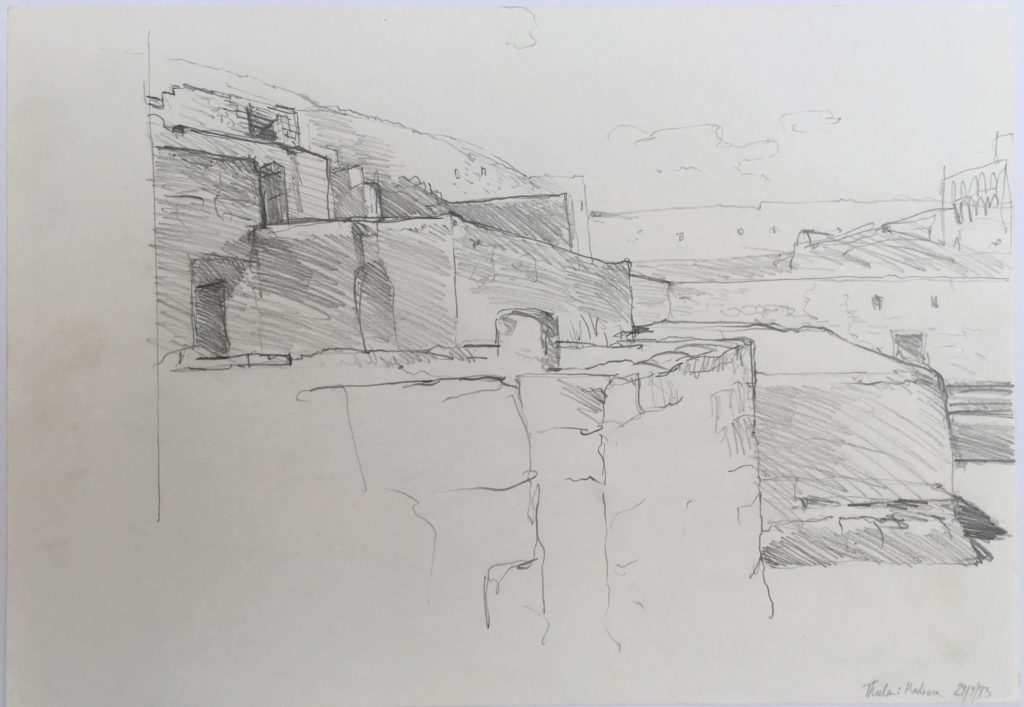

Sketching throughout the trip, I felt a strange paradox which has stayed with me ever since: while I had been drawing for as long as I could remember, would drawing help me to become a good architect? Or is my facility in drawing – the lack of resistance – a problem? I became fixated on the idea that drawing should be an act of humility. I believed that as an architectural novice I should avoid formulaic abstraction and rhetorical analysis in my sketches. I felt that drawing a building should almost be an act of worship, that it should involve complete and unreserved appreciation. My logic went that using hard lead ranging from 4H to 6H would create a resistance that would force me to look more precisely, and that the use of a hard pencil would favour cold objectivity over a superficial painterly effect. For me, objectivity meant that I would rely mainly on contour lines for the structure of the drawing. In my imagination, continuous contour lines worked like magic circles in which one could entrap the buildings.

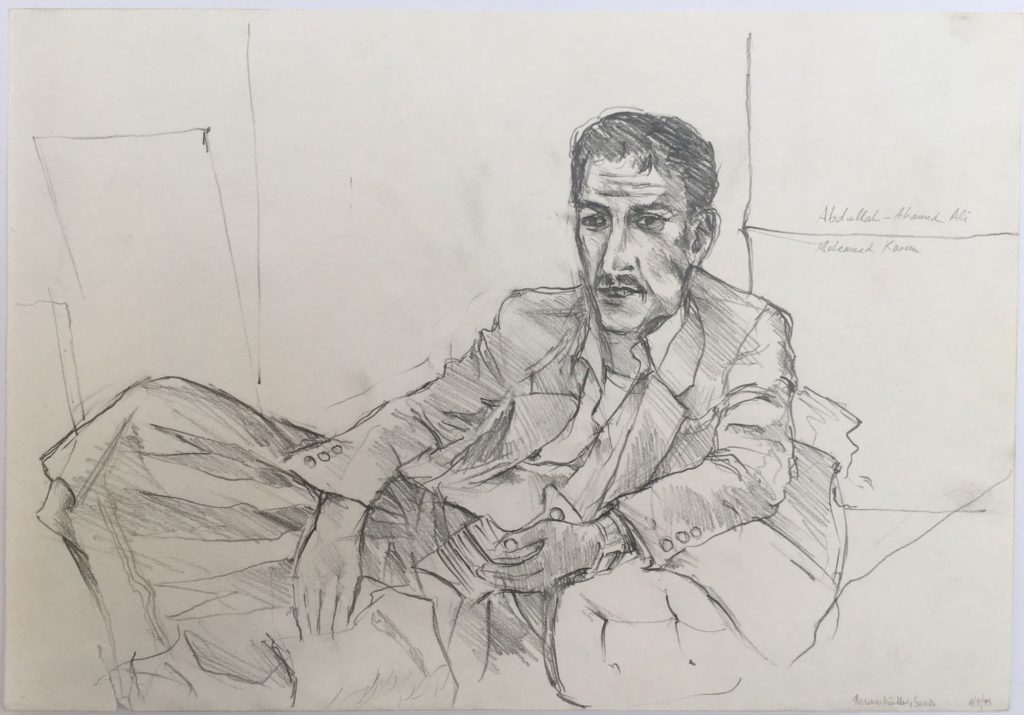

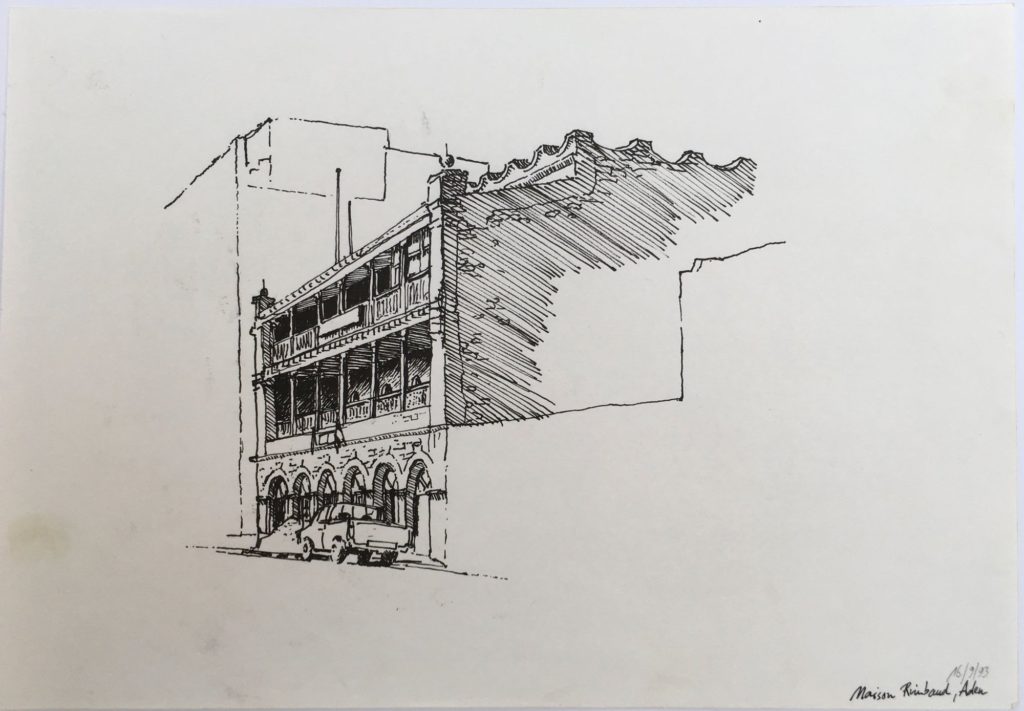

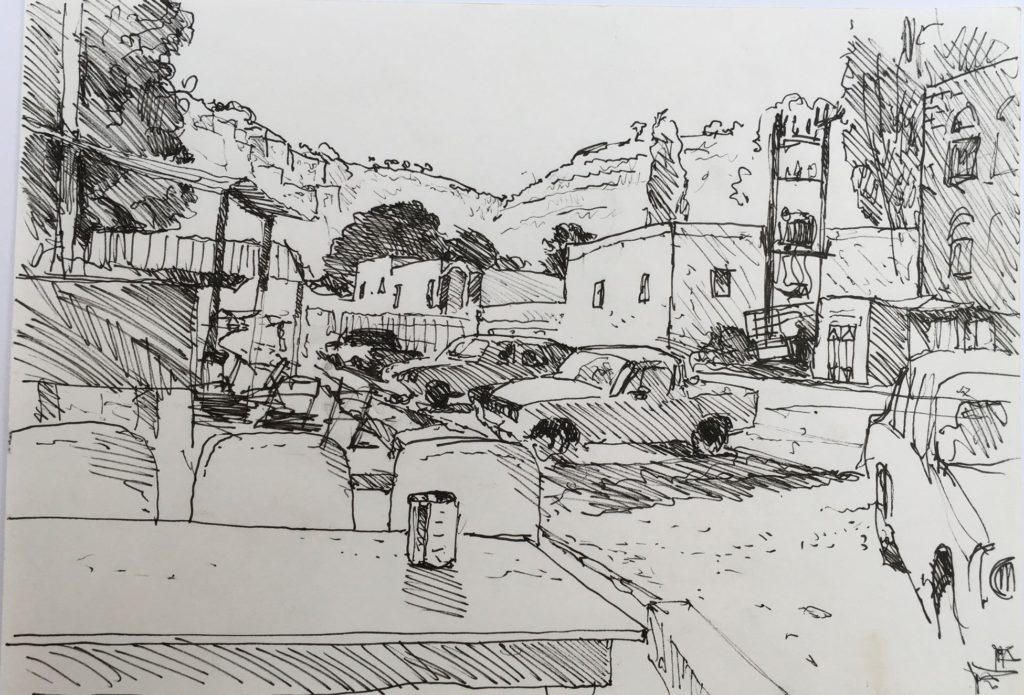

Only after a day of hard lead drawing would I allow myself the pleasure to turn to sketch social scenes with local people, mostly with a soft pencil or with an ink pen. As we chewed qat in the home of the village elder in the afternoon, my lines naturally became looser and the contours less rigid. The result was a strange chronological pairing of tense architecture drawings and animated ‘social’ drawings. Looking at these pairs today, I remember being torn between the methodological rigour of the hard lead drawings and the immediacy of the loose ones. I was not sure if drawing should be about condensing things towards an impersonal objectivity or whether it should capture things before they can be consciously understood. Confused, I would blame myself for the shortcomings of both kinds, for the lifeless rigidity of one kind and for the sloppy expressionism of the other.

Drawing felt different in 1993. It was before the internet and drawing still retained its original authority as a technique for documentation. Knowing that there was the possibility of a civil war, I felt a strange sense of urgency. I was aware that I might never be able to return, and that some of the buildings I sketched during my journey might be destroyed in the near future.