On Axonometric Drawing

In the work of our practice, since the very start, we have placed a great deal of attention towards drawing and representation. The recent exhibition in Antwerp—The Urban Villa—is a good example of our work, which is based on the combination of design with research; both of these two activities are deeply interrelated with drawing. While architectural drawing is traditionally associated with the production of building, in our work it has taken other roles too. It is in fact particularly central to our research work, or the attempt to produce architectural knowledge around a certain issue or theme.

By looking at this body of work and being able to look back at several years of practice, a limited number of representation techniques seem to emerge. According to Raphael, architecture is to be represented through three main notations: the drawing of the plan, of the elevation and of the section, in our work, the three main types of drawing are the plan, the axonometric and the perspective, with these last two drawn at time as a line drawing or as a (colourful) collage.

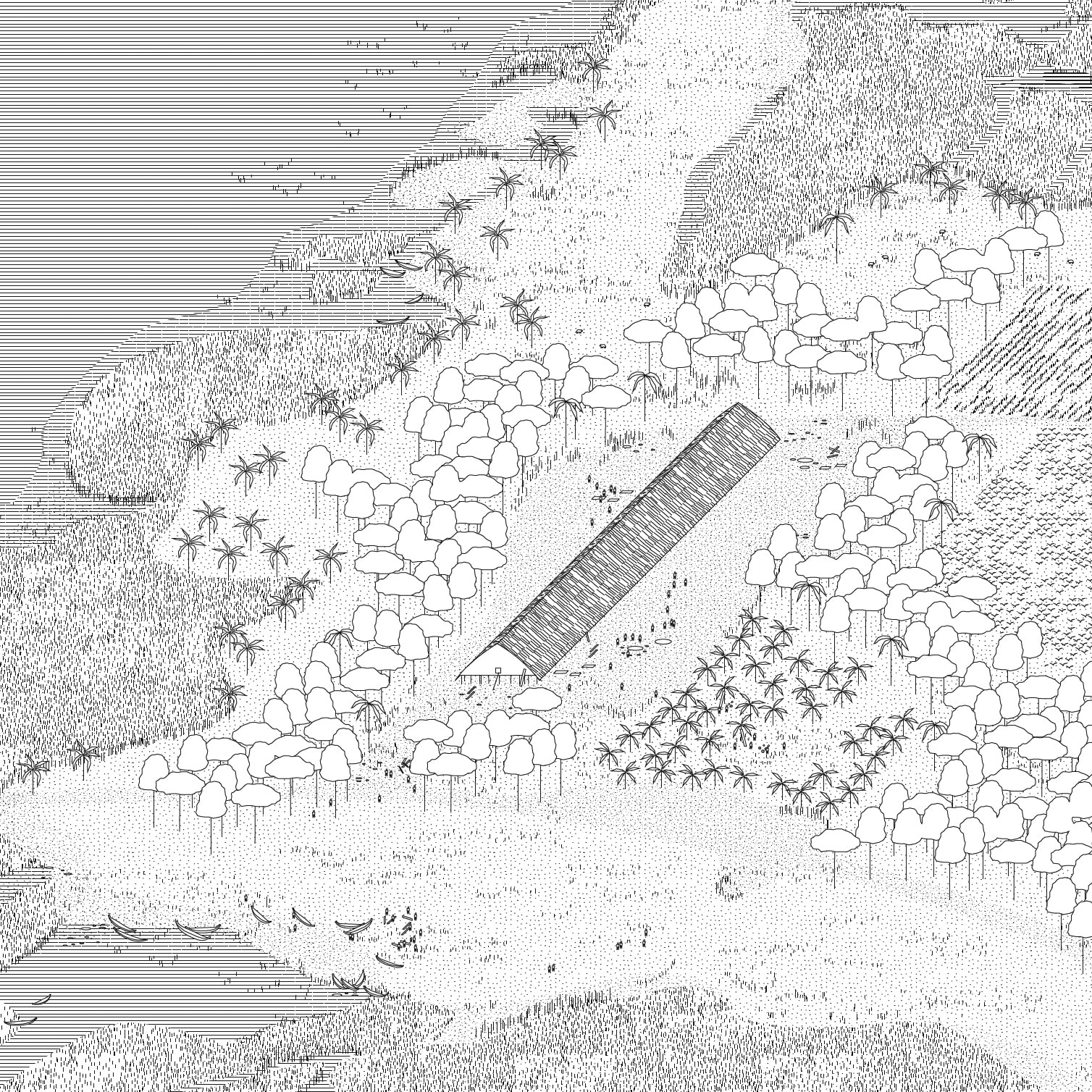

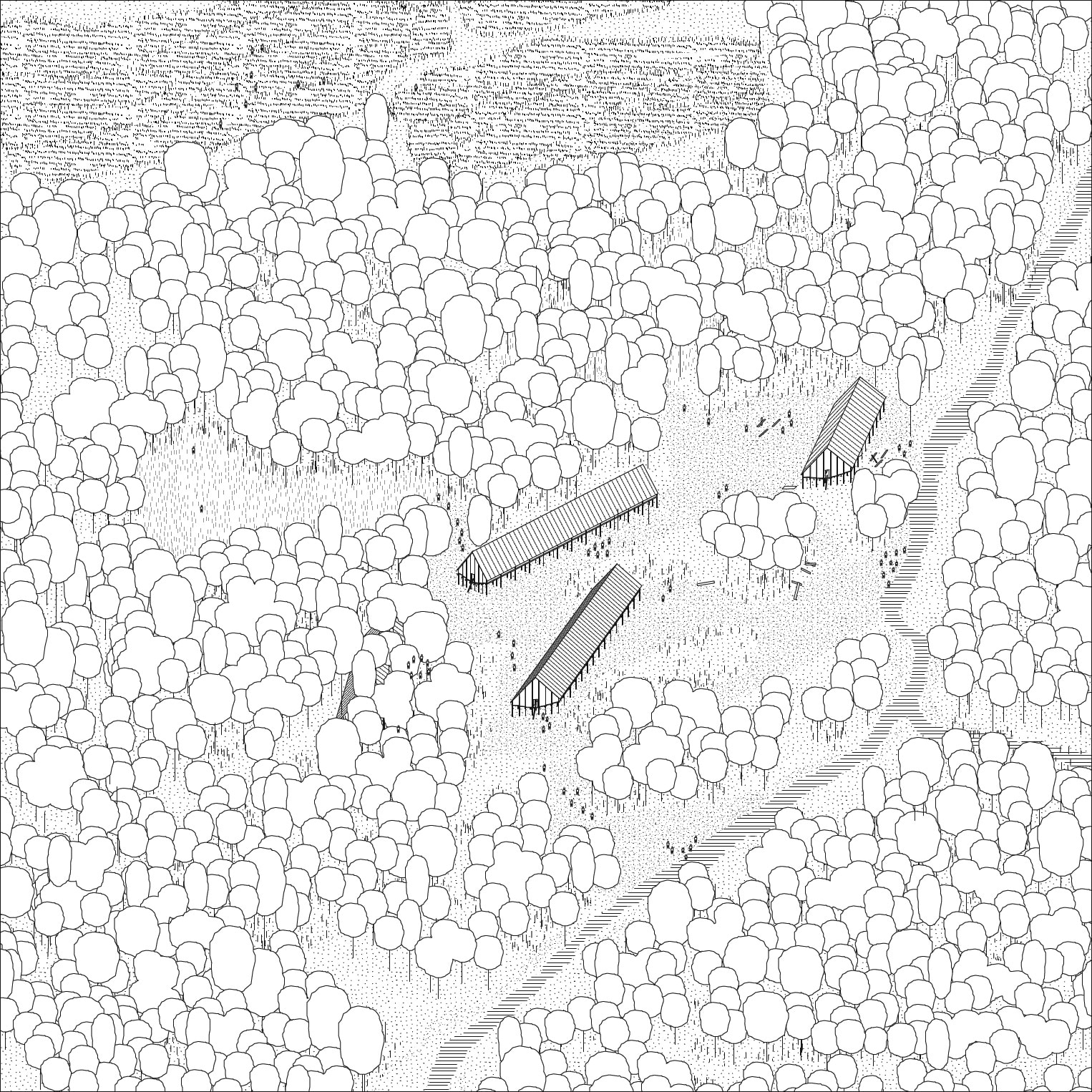

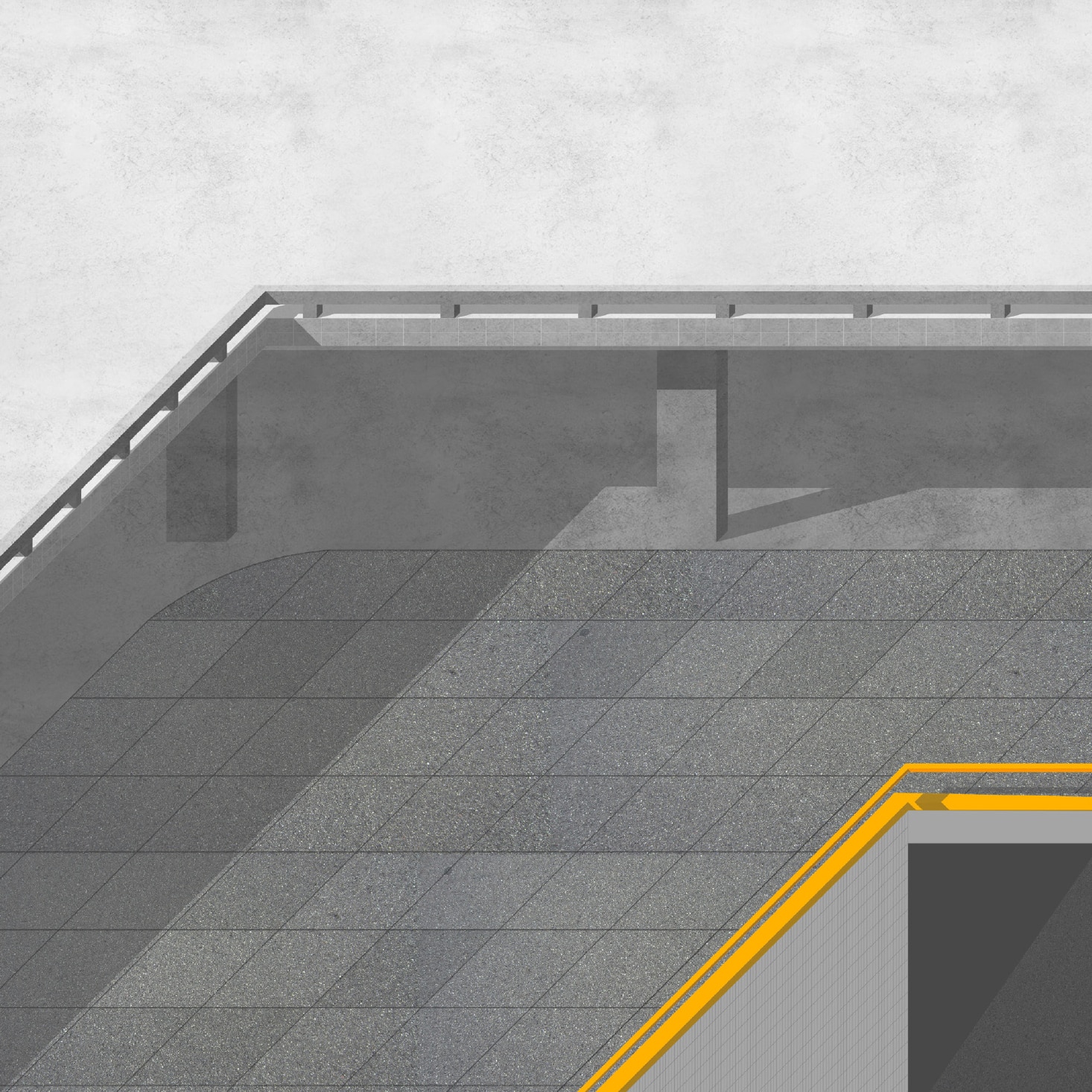

Among these three different types of notations, the axonometric has taken a prominent role, especially in our research work. Some of our recent investigations, such as the one on the architecture of the platforms (2021), the one on the longhouse (2023), and the most recent on the urban villa (2024), were based on the study of a selected number of cases, which were all drawn as axonometric drawings.

The choice of a similar type of representation is motivated by the comparative nature of our investigation and by the ambition to be able to look at these cases in the same way. Yet, while this would be valid for any type of notation, the choice of the axonometric representation—or of the parallel projection—is grounded in some specific features of this type of representation. Axonometry is a three-dimensional representation, thus able to bypass the abstraction typical of two-dimensional representation that can be difficult to be ‘read’ by non-experts’ eyes. Yet, differently from the perspectival view, axonometric representation has the capacity to keep together the legibility and accessibility of three-dimensional representation with the ‘objectivity’ and realistic precision of two-dimensional representations. Additionally, in axonometric representation the point of view is very particular. While perspectives are representations of architecture seen from a certain viewing point—as if the eyes of the viewer are looking at the object to be represented from a specific viewpoint—in axonometric representation, the observer is everywhere and nowhere at the same time.

Axonometric representation is objective, realistic, graspable, and can reveal multiple sides or dimensions of a certain architectural object, as if multiple eyes were looking simultaneously at the object to be represented. Yet, at the same time, the observer is nowhere, as the parallel lines through which an axonometric is built do not converge on any point of view but are as distant as the infinite. It is for this reason that some have said that the point of view of axonometric representations equates to that of a ‘God’s eye view’, an omnipresent eye, organizing and perhaps controlling space from above, revealing how such image has the potential to play a ‘Political’ role in our perception and understanding of architecture, and beyond that of the city.

It tends to present space in a non-hierarchical manner, without emphasising any specific element or preferred point of view. It removes the subjective gaze of the viewer, avoiding decisions about what to highlight or prioritise in the representation. Architecture is depicted through an equal and egalitarian perspective, without imposing preferences or explicit viewpoints. For this reason, axonometric representations have become a vital component of our practice’s system of representation. It offers a common, abstract, and impersonal view, illuminating the organisational logic of architecture. When representing an architectural intervention within its context, axonometric drawings emphasise the generic rather than the specific, softening exceptional elements and highlighting the neutral. They do not privilege a particular perspective or differentiate between foreground and background. Instead, everything is treated with equal importance, bringing the banal to the forefront and tempering the extraordinary. In this way, axonometric drawings reveal systemic urban logics that might otherwise remain hidden, focusing on broader spatial conditions rather than singular points of exception.

More than any other type of notation, axonometric representations serve as pedagogical tools. They educate the viewer’s eye, allowing them to decide what to focus on without imposing a subjective interpretation from the architect. These drawings do not present a predefined image of architecture, but instead support the viewer’s own interpretation, enabling multiple readings and the coexistence of diverse experiences. Rather than offering a single, fixed perspective, axonometric representations provide a multiplicity of snapshots for exploration.

Martino Tattara is an architect and professor at the Technische Universität Darmstadt, where he leads the Institute of Design and Housing. Together with Dogma, the architectural practice he has co-funded with Pier Vittorio Aureli, he has been working over the last twenty years on a research trajectory that focuses on domestic space and its potential for transformation.