One Small Sketch for Mankind

Raymond Loewy’s contribution to NASA was not rocket science. It was one small sketch for mankind.

But, like everything the designer ever did, the real significance of these fascinating sketches was outrageously bigged-up by their author. In his blindingly flashy oeuvre, their status is comparable to his (infamous) work for Coca-Cola. Carbonated beverages with herbal extracts and space travel were easily adopted into a portfolio bulging with exaggerated claims.

An interviewer in thrall to his reputation, John Kobler in Life magazine for 2 May 1949, extracted from Loewy an amusing quote about the ‘Callipygian’ curves of the Coke bottle. Loewy never claimed to have designed the famous vessel – that was the work of a Swedish glass engineer in 1916. But when lazy commentators read the article and made the assumption, he never bothered to correct them. In fact, his work for Coca-Cola was restricted to counter-top fountains and chest-freezers. But in this way were reputations made, and Loewy was a genius at reputation-management.

He was, with Henry Dreyfuss and Walter Dorwin Teague, a pioneer ‘design consultant’, opening his studio in New York in 1927. Loewy was a bravura egotist and his self-regard was epic. Pomaded, cologned, perma-tanned, pompadoured and with an ooh-la-la moustache, this French import was a gift to media looking for modern heroes who gave form to the American Dream.

And he played the game very well. Loewy hired a publicist called Betty Reese with a brief to get him on the cover of Time magazine, something duly achieved on 31 October 1949. Two years later, Loewy published Never Leave Well Enough Alone, his very clever memoir-apologia which The New York Times described as ‘instructive, brash, cocksure, occasionally funny, sometimes vulgar’. In 1952, this immaculately tailored man who put Chanel No 5 into his foul-smelling rubber scuba-diving wet-suits, was on the American Fashion Guild’s list of the best-dressed men.

Loewy’s involvement with government agencies began in the Kennedy era with unglamorous jobs for the Navy and Coast Guard before he executed his most enduring design: the paint job on POTUS’ Air Force One, still in use today. The Camelot White House was susceptible to design and to symbolism: another exotic, Oleg Cassini, designed Jacquie Kennedy’s signature pillbox hats.

Skylab was the first temporary space-station, in orbit from May 1973 to February 1974. NASA hired Loewy as a ‘habitability consultant’, although what he understood about space travel is not clear. Loewy’s own habitability criteria were defined by his Albert Frey-designed house at 600 Panorama Road in Palm Springs and his Park Avenue apartment with Chinese lacquer and ankle-deep carpets.

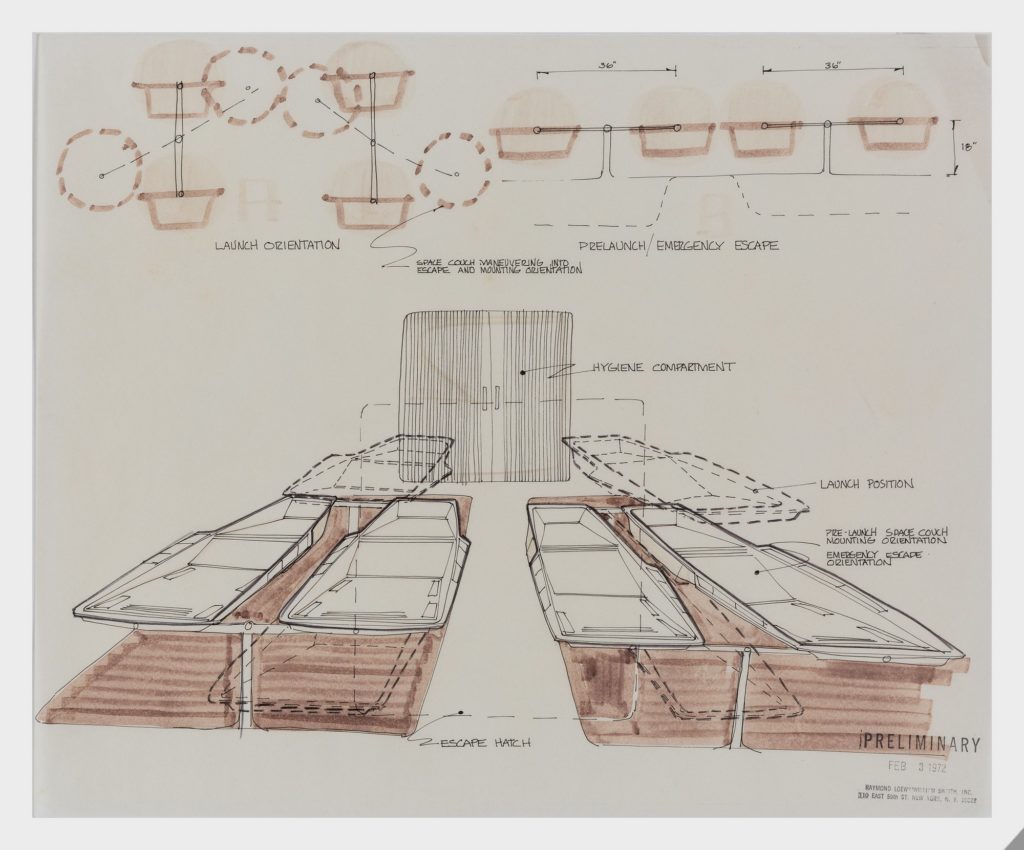

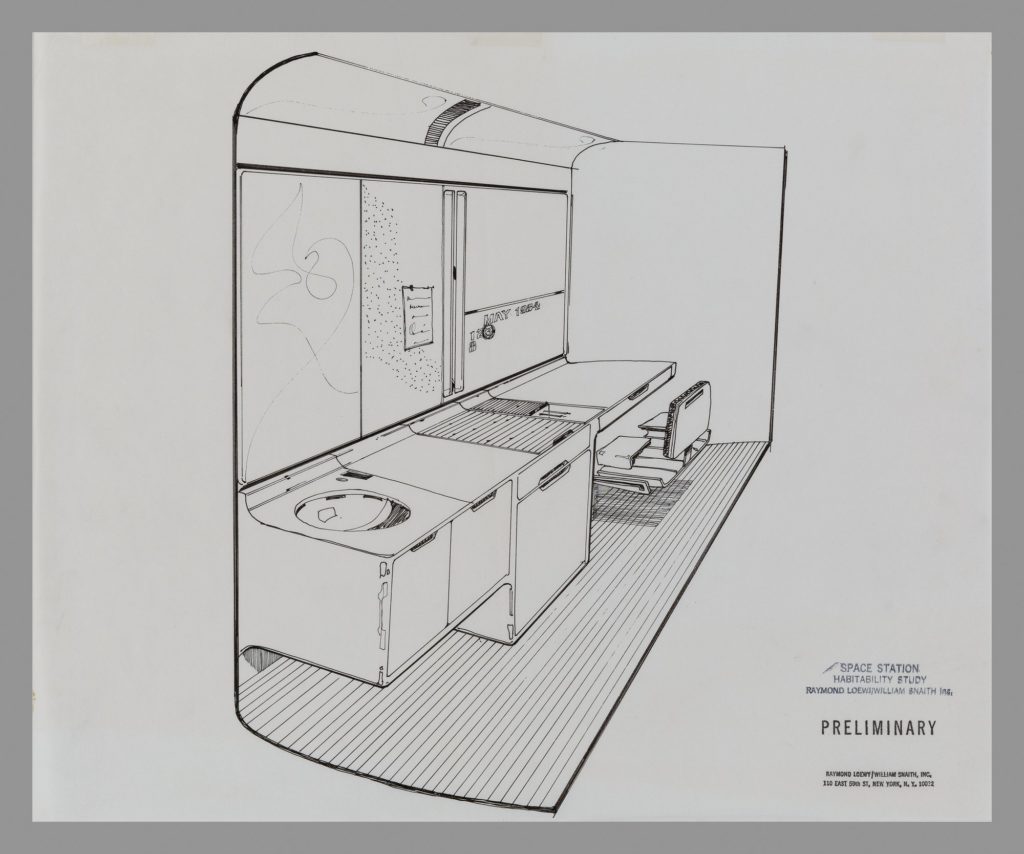

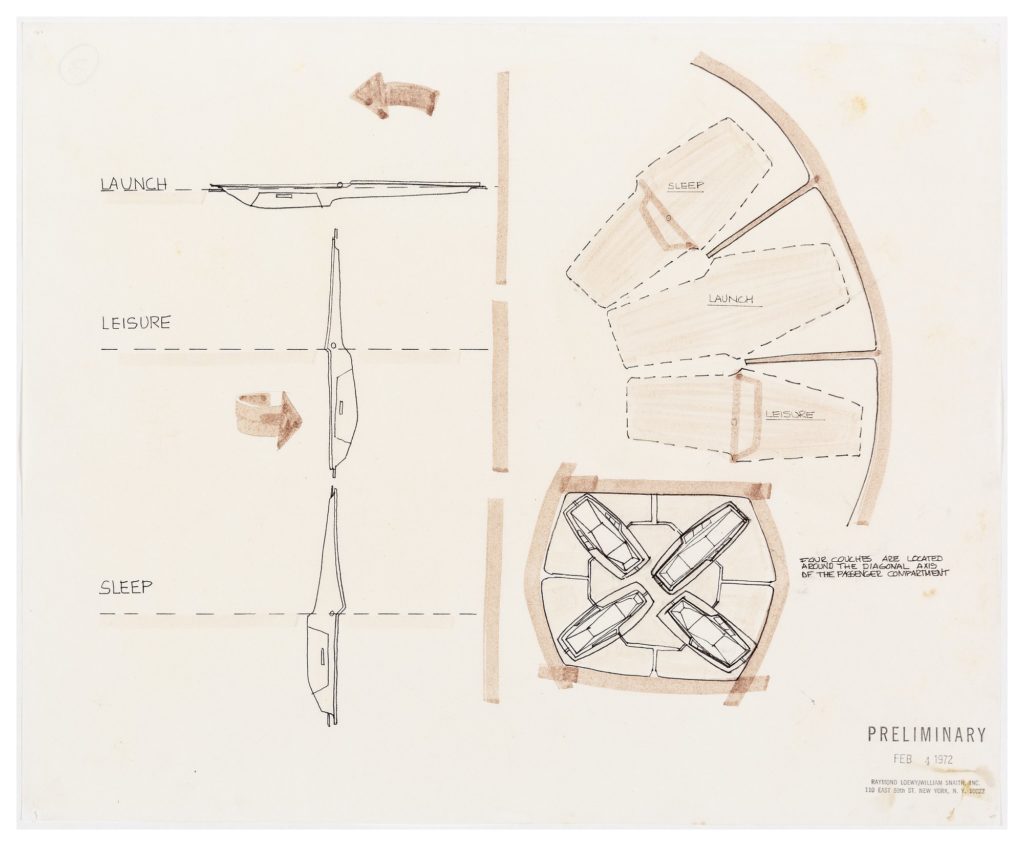

Loewy’s brief was to look at Skylab’s ‘floor plan’ and to consider colour and lighting. Nearly eighty years old at the time, the better to understand the challenges, Loewy cheerfully donned a space-suit for publicity photographs. The engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center at Huntsville, Alabama, were sceptical of interference from this louche outsider, but Loewy had the ear of the director, George Mueller. This allowed him to make his most useful creative suggestion: the provision of windows in Skylab, an innovation which the astronauts themselves, doing their PR duty, professed to be a great benefit.

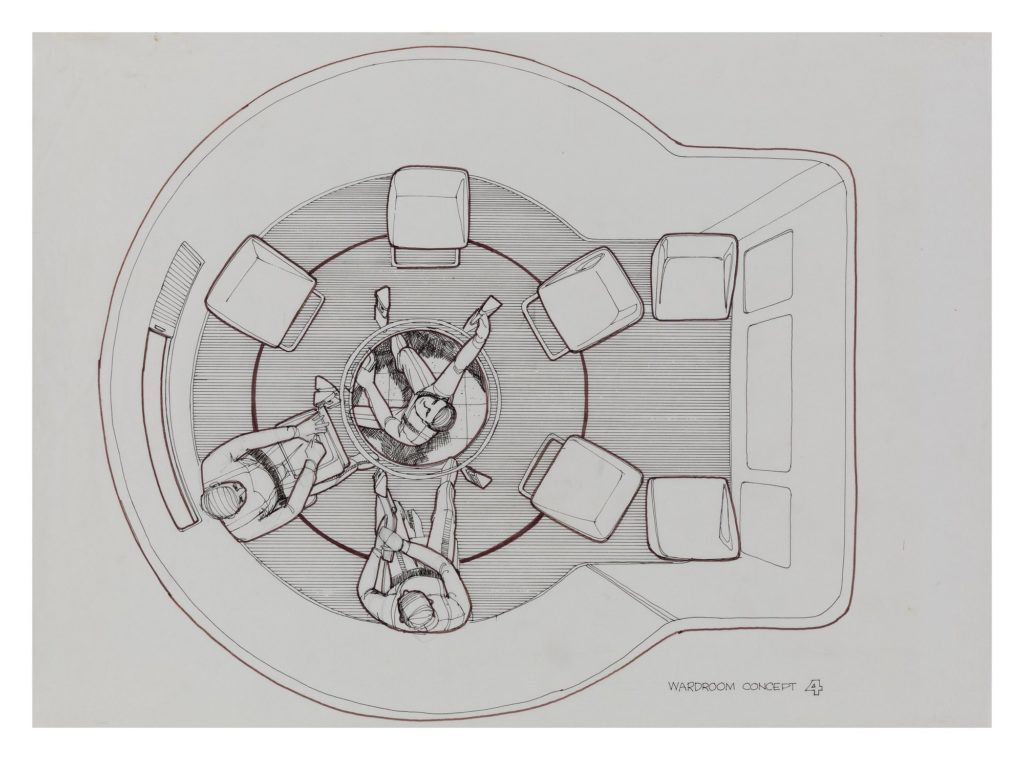

Otherwise, the Skylab drawings – credited also to Loewy’s partner William Snaith, even as their relationship was cooling – have a charming naivete. Artistically, they can be located in the genre of US corporate burolandschaft. Indeed, the sketches of furniture and fittings in the space station readily suggest Herman Miller/Charles Eames naugahyde-upholstered ‘executive’ mid-century modern.

These drawings say very little about space travel but are hugely eloquent of the status of the designer in twentieth-century America – in this case, one who schmoozed himself into mankind’s most heroic technical exercise. Raymond Loewy was a mile wide and an inch deep. But he was always flying high.

– Stephen Bayley