Resistance and the ‘Architecture of Pessimism’: John Hejduk’s House for the Inhabitant who Refused to Participate

Many people reach a point in their lives at which they realise that they should protest the status quo. Some people make the realisation but remain frustrated, stuck, or blocked from enacting the necessary change. How do we face, name, and act according to our most fundamental realisations and what happens when we do? John Hejduk’s House for the Inhabitant who Refused to Participate is an architectural work of images and text that thematises this situation and propelled his architectural oeuvre from the Wall Houses to the Masques—from the formal to the political.[1] I speculate that Hejduk, the architect, can also be interpreted as the inhabitant in this project. I have yet to find this statement in his writing, though he is well known for his outsider position, working predominantly through architectural drawings rather than buildings.[2] In this way, the project stands as a self-narration, which I find a most incredible tool for architecture, and is similar to the sort of work that novelists do with auto-fiction. So, if you like, this is a practice of spatialising the self-narrative that anyone could do. As an architect and author, this is something that interests me greatly.

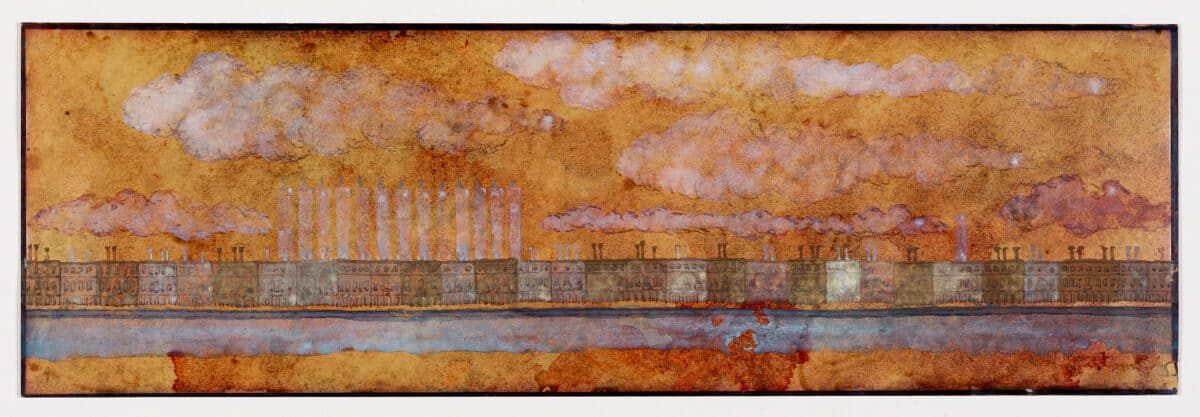

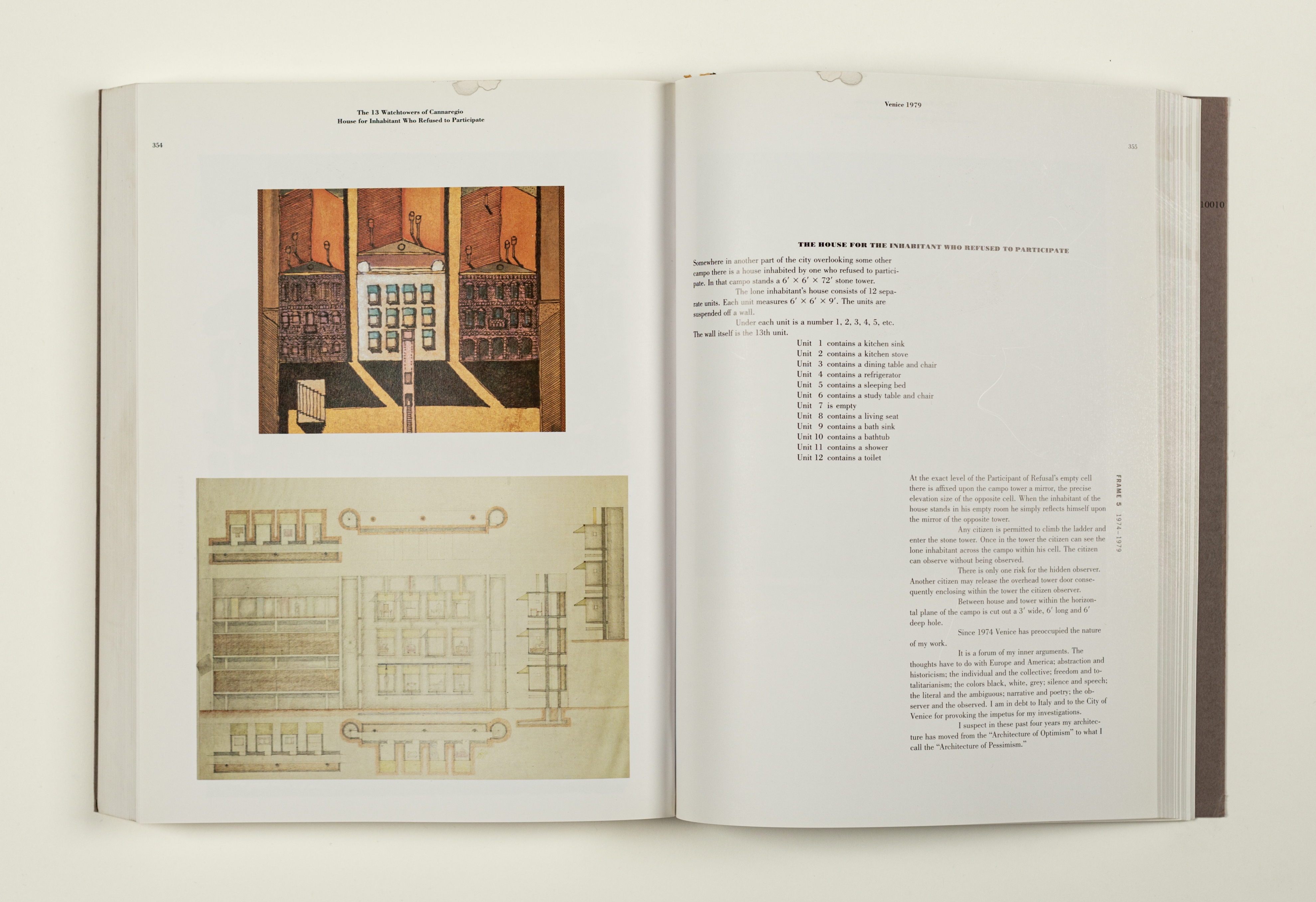

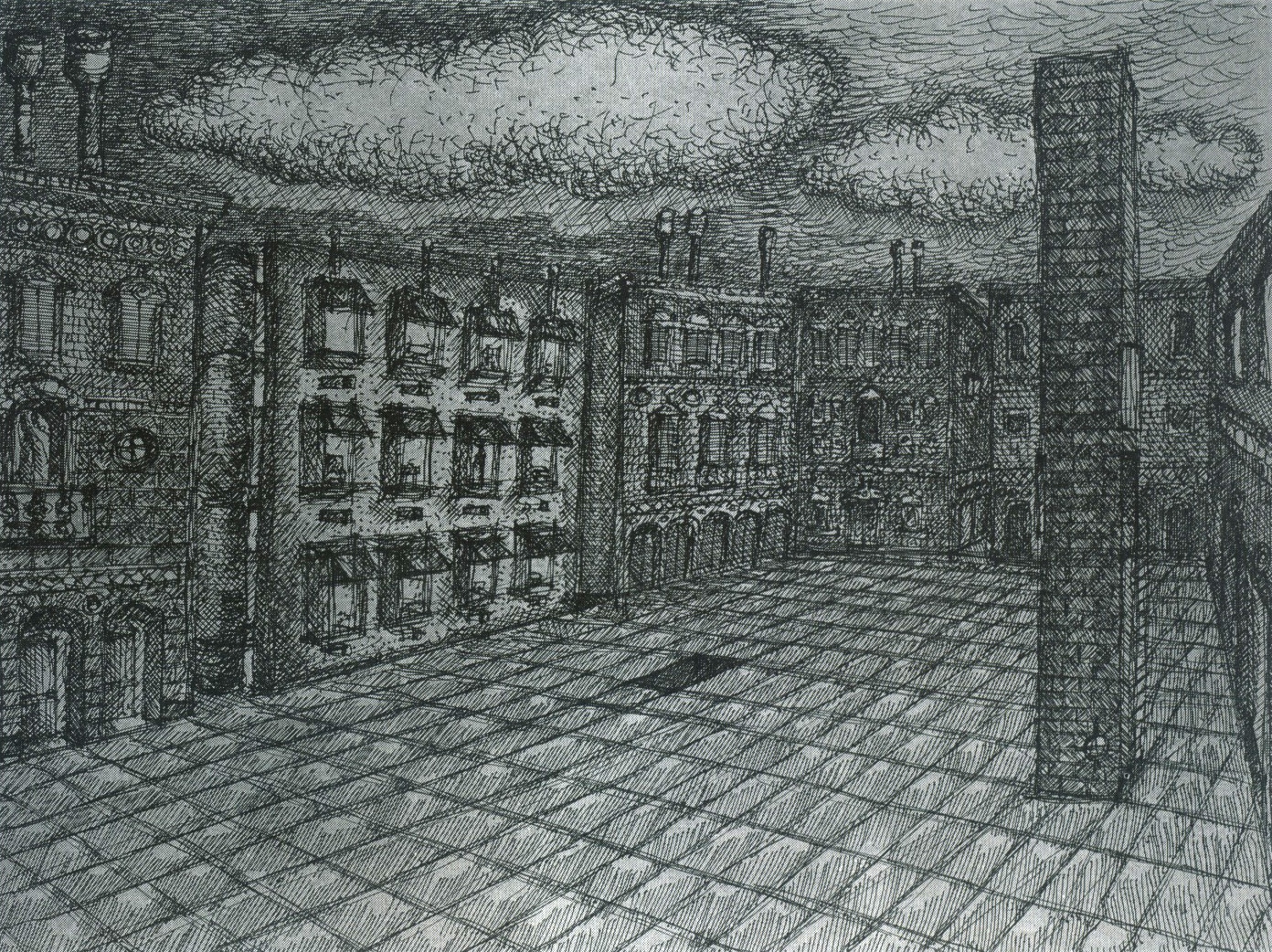

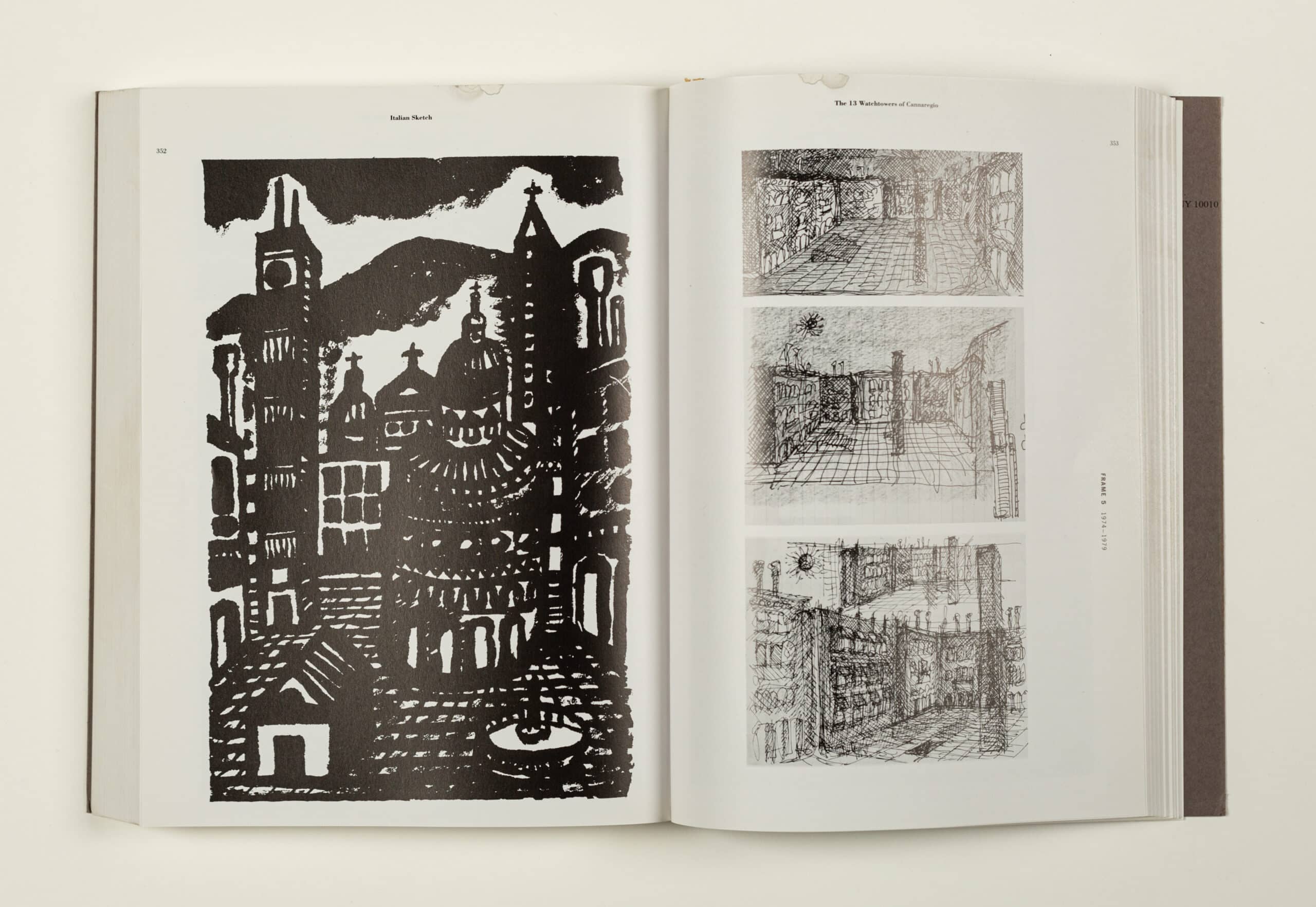

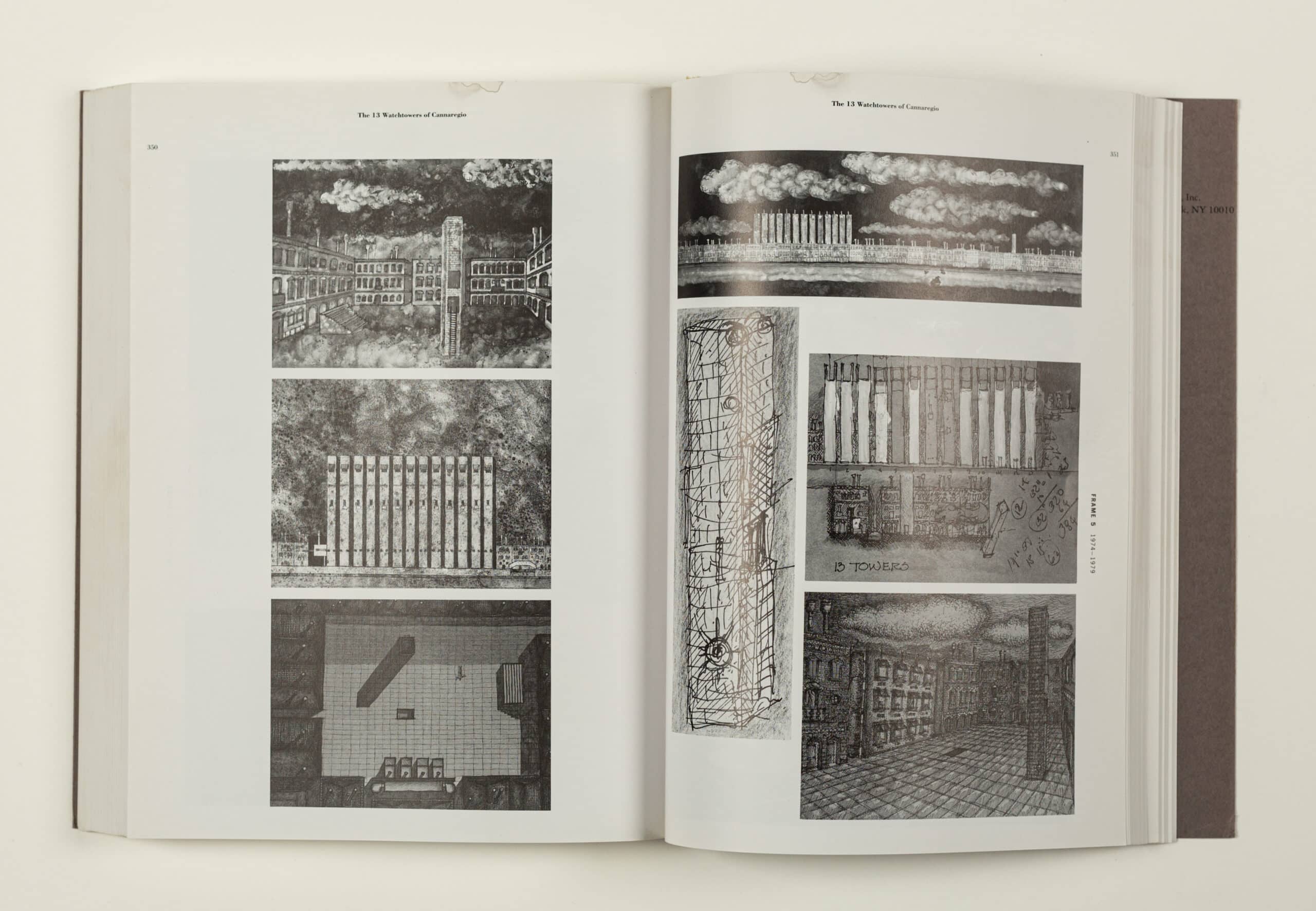

Hejduk’s House is sketched, collaged, hand-drafted, painted, and modelled in different mediums. The Drawing Matter Collection has two stunning watercolour and gouache paintings made with red-orange backgrounds with blue-white layered on top, thickening the intensity of the proposal. These two paintings are morose and foreboding in their colours, but playful with rhythmic houses accentuated through varied facades, chimneys and woolly clouds floating above the scene. One of the paintings (below) shows the ghost-like towers of this project and its sister project, Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio, situated a short distance from one another in Venice.

As with most of Hejduk’s work, studying all the different representations brings reward and nuance (see Marina Correia, Watchful Solitude: John Hejduk and Venice for more). This project was a moment of exploration of styles and expression for Hejduk. Some of the images have elements that others don’t. One of the hand-drafted drawings shows a human inhabiting various rooms of the house. One painting shows a human form lying on the ground outside the project. Otherwise, the images are empty of human presence. The text to the project (reproduced below) also helps to describe this unique house with rooms visibly hanging from one side of a wall with the circulation hidden on the other side. It is also indispensable to thinking about the project as a composition of poetic elements.

What exactly did the inhabitant refuse to participate in? Was the inhabitant placed in the house by society or did they build this house to make their protest visible? Can we assume that the ominous empty room of the house is a room of refusal? Why should the act of refusal be literally mirrored back to the inhabitant? Why should it be dangerous to inspect refusal closely? Why should watching the inspection of refusal become a spectacle? Is the hole in the ground a grave? If yes, for whom? Hejduk doesn’t clarify these points. I wonder why the inhabitant didn’t leave—like the characters in science fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin’s stories The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas or The Disposessed. Yet, if the inhabitant had left, then there wouldn’t be the house.

Hejduk states at the end of the text description for this project that his architecture has moved from the ‘Architecture of Optimism’ to the ‘Architecture of Pessimism.’[3] He describes the architecture of pessimism as something not necessarily negative, but something required to balance out the architecture of optimism. He says such programmes of pessimism existed in the Middle Ages, but modernism dismissed them.[4] Furthermore, he writes about Venice, Italy, and Europe as catalysing this change in approach:

‘Since 1974 Venice has preoccupied the nature of my work.

It is a forum of my inner arguments. The thoughts have to do with Europe and America; abstraction and historicism; the individual and the collective; freedom and totalitarianism; the colors black, white, grey; silence and speech; the literal and the ambiguous; narrative and poetry; the observer and the observed. I am in debt to Italy and to the City of Venice for provoking the impetus for my investigations.

I suspect in these past four years my architecture has moved from the “Architecture of Optimism” to what I call the “Architecture of Pessimism”.’[5]

Hejduk’s allusions are purposefully vague, but the social movements of the 1970s in Italy alone, garnered worldwide attention and must have provided some context for his thoughts. These included movements starting in 1968 like the ‘Potere Operaio’ (Worker’s Power), its eventual evolution into ‘Autonomia Operaio’ (Worker’s Autonomy); the splintering feminist struggle ‘Lotta Femminista’ (known in English by the resulting global movement ‘Wages for Housework’); the armed and militant group ‘Brigate Rosse’ (The Red Brigade); and many others. A pivotal theory within these autonomist leftist movements was the refusal to work. In that vein, there were multiple well-known Italian architects, such as Superstudio, that had taken up alternative practices as a protest against inhumane capitalist working conditions. Maybe Hejduk’s project is about watching those social movements as an American and fearing personal social judgement for interest in the anti-capitalist struggle.[6]

Considering Hejduk’s descriptive reflection on the shift in his work, I see this project as the last Wall House.[7] It is with this project that Hejduk completes the formal work of his former inquiries (e.g. the Texas, Diamond and Wall Houses) and fully awakes as a critical architect who comments on the sociological and political situation at hand.[8] He states:

‘The sociological aspect of the work, the narrative […] story telling begins with the Wall Houses. It’s not about black and white in the literal sense, but in a more philosophical way. It’s about alienation, paranoia, distrust, voyeurism […] peering over the wall. The periscope is a recurring theme. Like a U-boat captain—all the while he’s observing. But he’s also looking for something to sink. And the periscope and the other viewers in my houses all create that Cubist sense of compression, telescoping the view right up to you, so it flattens out. You’re right up against it.’[9]

Fundamentally, Hejduk is someone who did refuse to participate. He’s an architect who chooses not to build: instead, he draws. He removed himself so that he could observe sociological aspects that he’s ‘right up against’. The wall in the House flattens out each observational space. It isolates each individual function of the house, including the act of refusal. The inhabitant has to constantly pass through the wall, symbolising the present moment, in and out, back and forth to a series of compressed conditions, as they go about the daily tasks of everyday existence. The criticality, paradoxically reserved and poignant in these pieces, has been further expanded by Marina Correia’s doctoral dissertation Miniature Volume: John Hejduk and Venice. Here, she describes his Venice work as presenting design strategies that are non-hegemonic and relevant as precedents for contemporary critical practice. I would go further—every adult living on this planet should be thinking about their role in challenging the banal and normalised causes of ecological and social suffering, today. Hejduk’s work is abstract; it doesn’t define the exact condition that is being refused. This abstraction makes it compelling as a philosophical premise. To refuse is to be pessimistic and, when we look closer, it also makes space for something else.

Throughout his career, Hejduk discovered things about architecture and life in his work and took each project as a step on a path. Even as he comes to a recognition about society, architecture, or himself, he does not become cynical. He continues with the work until it opens up the next chapter. The Diamond Houses revealed the importance of the hypotenuse as an existential condition, a two-dimensional plane started to act as the marker of the present moment.[10] This proposition about time and phenomenology was transformed and continued in the Wall Houses. The Wall Houses then opened up the narrative potential of alienation, voyeurism, etc. Eventually, in the House for the Inhabitant who Refused to Participate it becomes possible to not only peer out over the wall, and the present moment, but to find the world outside, the urban context, and the reflection of the self. This is a breakthrough moment because it confronts the dialogue between grounded site history and architectural actions. The mirror makes the inhabitant (and the architect author) self-aware in a new way; everything changes. He lets his wall(s) down. Hejduk’s later work moves forward with an urgency found in this project; the later Masques are set up through dramatic socio-political constellations of figures, lifelike in their programme, materiality, and site.

For me, Hejduk’s work has often been enigmatic, difficult to interpret, and at the same time deeply inspiring. However, if it’s possible to use self-narration in architecture, then architecture can be for everyone; architecture can be liberated from all kinds of parameters if it is used this way. Further, if it’s possible to materialise things like the existential phenomena of the present moment and then work through this problem on a subjective and personal basis, then the work of pessimism in architecture is clear and valuable to me. Hejduk’s ‘architecture of pessimism’ compels the liberatory self-narration of the project, and I believe it can continue to provoke architectural practice in a unique way for our present moment.

In the book Ricochet, artist and author Alex Head states that:

‘If atomization and human loneliness are the necessary conditions for the ideological manipulation of a cult, locked into a march of death, there are certainly striking similarities between the world of the early 21st century and totalitarian Germany and Russia. […] Unregulated neoliberal economic policy, to the extent that it has successfully dominated human subjectivity, has created a world of fractured persons who pivot between the fascinating spectacle of extinction and an unbearable feeling of total superfluity. And technology has played a significant role in the current unmaking of social bonds and the joy of co-dependency.’[11]

For me, this summation articulates how the present moment is not just related to time but to the deep alienation that my cultural and social existence has to the world. It is an alienation so tenacious that the agency to change feels impossible. But it is not. Through work, humans have made the social world and each individual makes their own life. This means that through work we can change the social world and change our lives.

It would be too simple for me to end there. Even if I state in general terms that our present moment is defined by the economics of exploitation and digitisation and thus one of global crisis and subjective alienation—and then also make the claim that this is something we can change through work—I have yet to truly argue for a ‘pessimistic’ approach. To continue requires that I take a personal position about our contemporary moment. According to the calendar, we are no longer living in the 1970s. And yet, many hard-won battles for social progress are being rolled back as I write. It may seem that optimism is the only way forward during a struggle, but the benefits of the balance of Hejduk’s ‘pessimism’ might be more practical for the urgent work required.

What might contemporary optimism be? Perhaps it would be an updated modernist approach in which the parameters are accepted, encompassed, and opportunistically altered. I’m thinking of Diane Lewis’s personal and tactical analysis of Mies (as well as the architects of Cathedrals) as taking on a Faustian pact—where it is risky but possible to ‘beat the devil.’[12] For Lewis, ‘beating the devil’ meant upholding progressive ideals that fought against fascism and promoted emancipatory civic institutions. I’m also thinking of the architects and curators of the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara’s manifesto of FREESPACE. In particular, point three of the manifesto states: ‘FREESPACE celebrates architecture’s capacity to find additional and unexpected generosity in each project—even within the most private, defensive, exclusive or commercially restricted conditions.’[13]

However, I just don’t know if it is possible to beat the devil anymore—the devil seems to grow stronger and more violent by the day. I often feel pretty ineffective in participating and looking for generosity in an economic system that seems to increasingly constrain personal and socially creative worlds. Our times require the visionary approaches that Lewis, Farrell, and McNamara advance, yet I think it’s important to warn against any simple interpretation: the work of system change does not look like a sly smile and a handshake with power.

Another (somewhat) optimistic approach is that of the ‘peninsula’. The theoreticians Ina Praetorius and Frederike Habermann have separately explored the care-centred economy and its possibility for existence not in the exile of communes acting as bubbles outside of current systems, but instead as actions that contribute to the collective work of demystifying and removing subjective identification with the current system.[14] Such ‘peninsulas’ might be something as small as public bookshelves or as large as institutes like the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales which offer short-term courses or full degrees focused on creating a more sustainable world, as well as producing policy advice to interact with governing bodies.

In itself, the ‘peninsula’ is optimistic, yet framing it as such could doom its vanguard nature to erosion. Change requires negation of the past in the present. Effective change requires a confrontation with dread, sorrow, guilt, anger, grief, and death—pessimistic ideas. For this I find author and ecological activist Joanna Macy’s practical and spiritual teaching powerful.[15] She talks about ‘honouring our pain for the world’ to validate how personal concerns are shared beyond personal ego and can thus reconnect us in an ability to suffer with the world. Such conviction in negative passions liberates individuals to compassionate collective belonging.

Returning to Hedjuk’s House alongside his other projects of that period, we find a whole series that contemplates such pessimistic ideas. There is the Cemetery for the Ashes of Thought; Silent Witnesses (which Mark Dorrian has explicated here on Drawing Matter in relationship to War and Nuclear criticism); The New Town for the New Orthodox (An [anti-]town-planning project, where the proposed town is abandoned once the original inhabitants die); an analysis of Villa Malaparte (including the reflection that leaving the house offers a vision of a final exit); and then the paired projects of the Thirteen Watchtowers of Cannaregio and the House for the Inhabitant who Refused to Participate.

And in this last project there is the wall, the ‘empty cell’, the mirror, and the human-sized hole in the ground. Imagine yourself in the ‘empty cell’ measuring 6 x 6 x 9ft: just you in that small room looking out across the Venetian campo. There are people in the square; possibly they see you. There is the tower, with the mirror on it reflecting your own image (an adult standing alone). There is the hole in the ground, in which you imagine yourself once you’ve died, buried under the surface of urban rituals. All of these empty elements become full. They are full of the personal and daily work of protest, visible resistance, reckoning, poetry, worldliness, the unknown, and ultimately exactly what we are looking for… the agency to change.

Notes

- John Hejduk, Mask of Medusa (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989) is the most comprehensive collection of his works and is used as the main reference for this article. The Wall Houses and the Masques were project types that Hejduk worked on in iterations, forming series of inquiry through drawing.

- Architect Daniel Libeskind does refer to Hejduk in the introduction of Mask of Medusa as an ‘anomaly … an architect who refuses to enter into anyone’s service.’ Ibid., 9.

- Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, 355.

- Ibid., 63 & 90.

- Ibid., 355.

- Some resources that helped me to think about this context include: Ross K. Elfline, ‘Superstudio and the “Refusal to Work.”’ Design and Culture 8 (2016), 55–77.; Patrick Cuninghame, ‘Italian feminism, workerism and autonomy in the 1970s’, Amnis 8 (2008) <https://journals.openedition.org/amnis/575>[Accessed 5 April 2024]; Aaron Bastani and Federico Campagna, ‘Autonomia and the year of ’77.’ Audio recording, SoundCloud, n.d. <https://soundcloud.com/novaramedia/autonomia-and-the-year-of-77> [Accessed 5 April 2024].

- Hejduk also ends this section of Mask of Medusa with two short texts that allude to a transition in thinking regarding the wall. Hejduk, Mask of Medusa, 97.

- Ibid., 125.

- Ibid., 96.

- Ibid., 90.

- Alex Head, Ricochet: Cultural Epigenetics and the Philosophy of Change (Norway:Ljå Forlag, 2021),203.

- ‘Diane Lewis – Dr Faustus and the City: New York and Berlin. Video recording, Youtube, 20 May 2015 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMqevt4prTI>[24 April 2024].

- Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, ‘Freespace Manifesto’, Reading Design (2017) <https://www.readingdesign.org/freespace-manifesto>[Accessed 5 April 2024].

- Ina Praetorius, ‘The Care-Centered Economy: Rediscovering what has been taken for granted’ (Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2015), 58. <https://www.boell.de/sites/default/files/the_care-centered_economy.pdf>[Accessed 24 April 2024].

- Joanna Macy’s teachings are mostly known as ‘Work that reconnects’. They are far-reaching, including many people, books and co-creative events that evolve these insights. Joanna Macy, Introduction to honoring our pain for the world, 1 November 2014. https://workthatreconnects.org/resources/introduction-to-honoring-our-pain-for-the-world/ [Accessed 24 April 2024].

Anna Kostreva is co-founder of Plural Studio, an office for architectural design and critical inquiry. She is a graduate of The Cooper Union School of Architecture, NYC, and the recipient of a 2009 Fulbright Grant for research on post-apartheid urbanism in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has taught architecture at TU-Braunschweig and The University of Bath as well as urban research at Humboldt University in Berlin. She recently published her first architectural novel, Seeing Fire | Seeing Meadows (UK: Plural Studio, 2023), which incorporates architectural projects as fundamental elements of the narrative.

– Anthony Auerbach