Fresh and Surprised

Indische Buurt is a suburban area at the eastern edge of Amsterdam that is rich with diverse ethnicities, building ages and spatial experiences. The streets are named after islands and, as a territory historically built upon reclaimed land, there is an overriding feeling of an archipelago: islands that are places around each other and over the years disengaged. The flat landscape comprises diverse shaped expanses of land and water, of city and park, all made magical when they meet and merge through their shapes and changing qualities of light. The green and blue place that defines the eastern-most part of Indische Buurt is called Flevopark.

In the late-nineteenth century, parks in western Europe were often designed as counter conditions to the city. They provided a special extent of character and were designed as healthy green experiences – a kind of alter ego to urban intensity that was set apart, exotic and ‘other’. Flevopark was designed to create a place to escape the city, closer to the eastern water edges, and has become known as the ‘Hidden Green Pearl’ of Amsterdam. But, like a tree growing up through iron railings, the expanding city found itself hampered by historic rings of infrastructures, themselves legacies of the 1950s and 70s planning for access and speed. Flevopark inadvertently became closer to the centre as the city grew, creating a strange proximity between the city and the ‘other’.

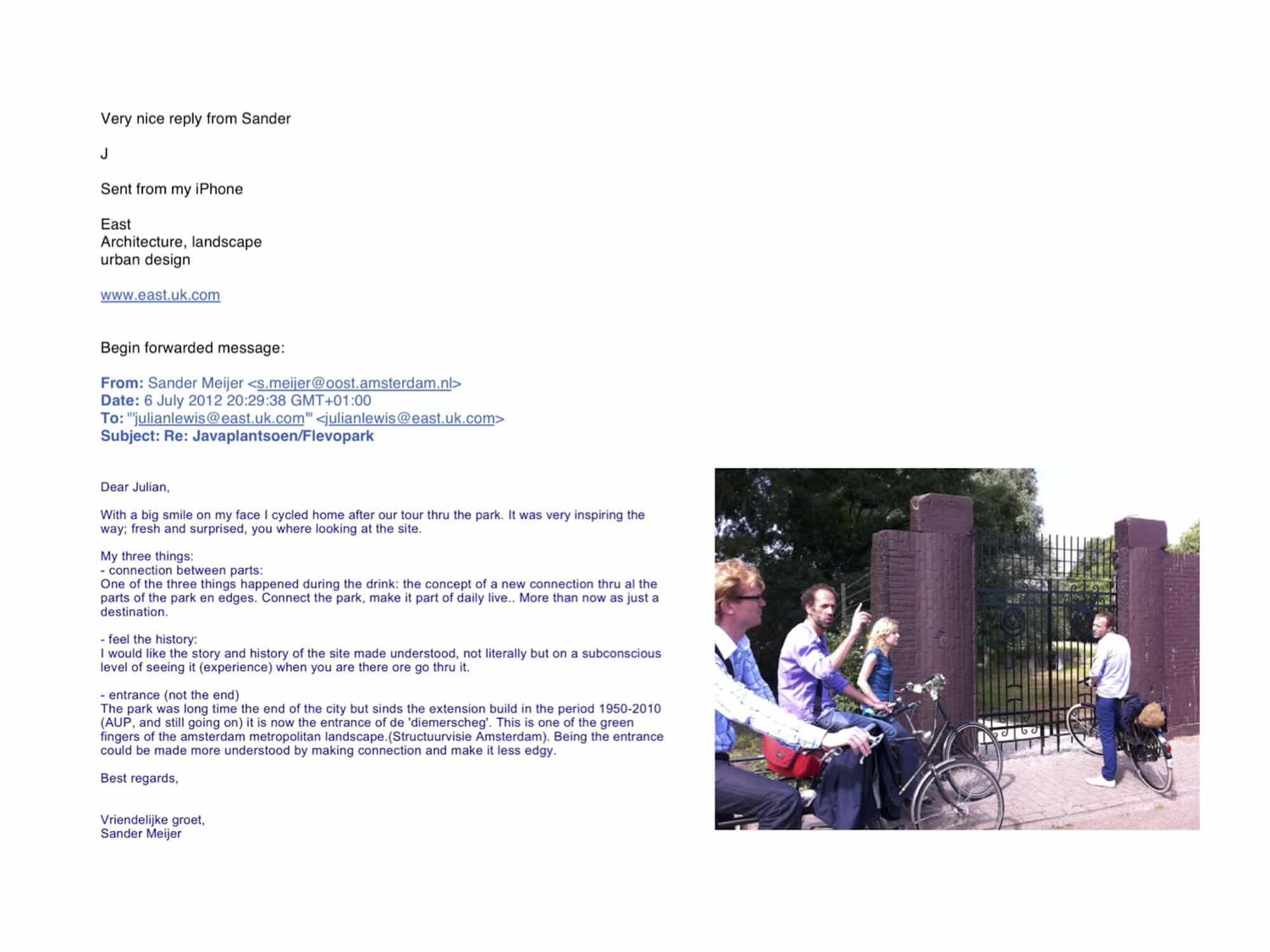

Invited by TU Delft to explore new strategies for transformation around Flevopark, one sunny afternoon we cycled around the area with the Council officers who manage the park. [1] As Londoners, we felt a sense of exhilaration at having been given licence to view the places that they knew so well with fresh perspectives, and even naivety. With no brief for architectural or urban proposals, our movement around the site was enriched as an experience of discovery without judgement. The uplifting feeling of exploration, shared openness, the mixture of knowledges and not-yet-knowing, was beautifully captured in the park manager’s follow up email to us, shown here alongside a photo of us looking at one of the entrances to the park, where a hidden Jewish cemetery, leading to a reclaimed green at the edge of the water, abuts a university campus.

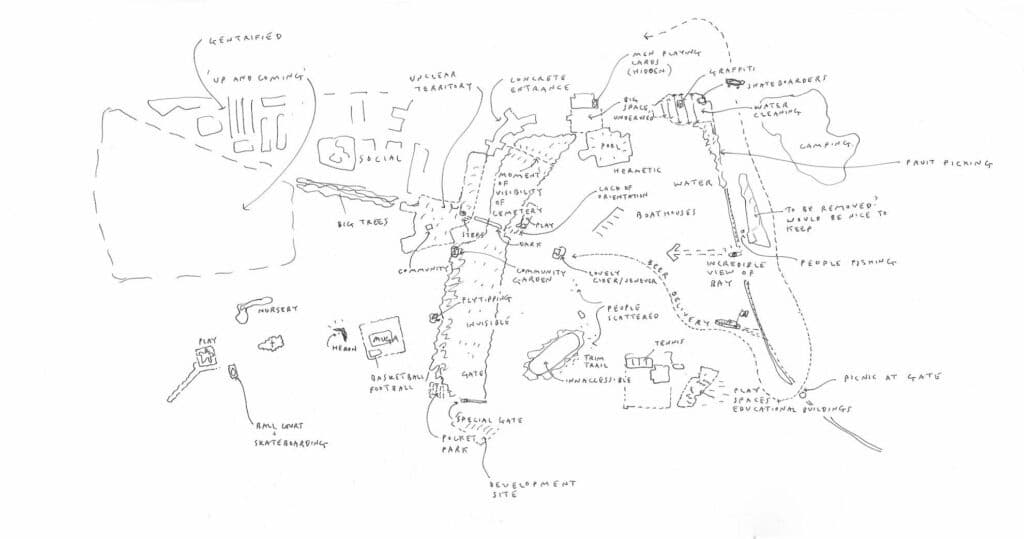

The so-called ‘hairy drawing’ presented here is one of a series of early drawings used to scope interest and identify proposals and sits somewhere between documentary and proposition. I now realise the drawing evokes the form of the cycle ride itself, combined as a collective condition in memory and on paper. It mixes experiences, speeds, vistas, atmospheres and scales, portrayed with looping lines, edges, fragments and destinations.

Made rapidly and in a single sitting, I wanted to sidestep the conventional hierarchies of the urban structure we had traversed and instead to render, with as much equivalence as possible, specific aspects of the territory of Indische Buurt and Flevopark. In particular, the drawing was about simultaneously tracing and shaping the spaces created at the edges — those uncertain areas of unforeseen consequence cast across the interface between the eastern park and the expanding urban settlement.

By proximity, the mundane is dramatically juxtaposed, setting ‘men playing cards’, ‘fly-tipping’, ‘heron’, ‘community garden’, ‘Jenever’, ‘concrete entrance’, and ‘picnic’, within the same frame. The ‘plan’ format allows for a spatial significance to become visible — edges and figures shaped as characters of distinctive identity. The drawing is a provocation as nothing in it is factual or ‘surveyed’. It articulates a condition that has never been designed but is here spatially imputed as a particular reading. Highly ‘judgemental’ you could say. But this is design that uses the place itself and relationships of space, material, use, figure and character, to help define something else, sometimes subtly, other times boldly.

The drawing is a brief, even a stimulus, for how we developed the proposals to ‘stitch in to’ the various parts of the place, enabling the edges to become animated, more ‘urbanised’ and used, to access the sublime invisibility of the cemetery, to open up with bridges, to cycle, walk, rest and play. The contingent role of the drawing remained integral to the body of the proposals themselves, which sought to curate an incomplete whole using new and existing differences and to revalidate the park and city as good companions.

This hairy drawing, and drawings like this that we have encompassed as part of our design methodology at East over the past 25 years, is essential as a process of provocation in testing how significance gets spatially allocated. Sometimes shared and sometimes individually made, these drawings are a form of thinking that helps us to guide the pleasure and audacity of creating architecture using the imaginative capacity of places as reflected through drawing.

Notes

- Renewing city renewal was the subject of a research programme conducted jointly in 2011 and 2012 by De Nijl Architecten, the KEI Knowledge Centre for Urban Renewal (now Platform31) and Delft University of Technology, with funding from the Netherlands Architecture Fund (now the Creative Industries Fund NL). The programme involved exploring the task, conducting a closer analysis of four study areas.