Stirling at Stuttgart: Rear View / Up Views

Rear Views

I joined the Stirling office in September 1976, working late hours through the length of four years until my return to Dublin towards the end of 1980. Straight out of college and into my first proper job, the critical years in my formation as an architect. I had been encouraged to send in my portfolio by Ed Jones, a motivating mentor to so many of my generation in the studios at UCD. My thesis project was a Constructivist-inspired, Leicester-influenced newspaper office at the apex of a triangular urban block on the axis of Dublin’s O’Connell Street. 9 A1 drawings photographed in black and white, printed at A5 on glossy paper, enclosed with a hand-written letter expressing my enthusiasm for the work. I spoke briefly to Stirling on the phone one Friday evening – a very short interview: ‘Nice drawings actually, when can you start?’ – and turned up for work at 75 Gloucester Place the next Monday morning. A perfunctory interview with Michael Wilford and I was despatched to the basement, where I spent most of the days and nights of the following four years.

When I joined the office, Peter Ray and Crispin Osborne were upstairs in the front room, steadily working on finishing Runcorn phase 2. Catherine Martin ran the office administration. Jim and Michael sat separately installed at their stations the bow-windowed back room. Downstairs, buried in the basement, I was to work with Russell Bevington and Ueli Schaad on the ongoing run of competitions and unbuilt designs; Doha, Florence, UNEP Nairobi, Rotterdam, etcetera.

The mornings began quietly with classical music on Radio 3, by mid-afternoon the air was thick with Bevington’s Rio 6 cigar smoke, a habit he’d picked up from his time working with John Miller. Evenings were loud with Schaad’s selection of Rolling Stones and Bob Marley on his reel-to-reel tape recorder. I know its only Rock and Roll but I like it. Lively up yourself. Conversation ranged from the possibility of reincarnation in the form of your chosen classical composer; Bevington bagged Beethoven, Schaad opted for Brahms and I was assigned to Schubert. Lists were a daily pastime in those team-working days; name your top ten Corbusier buildings, top ten buildings of all time, top ten Dylan songs, etcetera.

Stirling dropped down from time to time throughout the day, sometimes bringing wine and cigars after his dinner at home, keeping a careful eye on every detail, keeping the competition designs going in the direction he wanted things to go. On one such occasion, late in the evening during the Stuttgart competition, Jim appeared from upstairs while we were engaged in one of those regular downstairs chats. The discussion had started out from Alison and Peter Smithson’s Without Rhetoric, the Georgian repetition and cool rationality of the terraces at Bath compared with the more finicky sensibility evident in Ted Cullinan’s residential block attached to the Olivetti training centre at Haslemere. Cullinan had been responsible for the conversion of the Edwardian head-house, with Stirling adding a Victorian-inspired conservatory, ramping down dramatically to upset his carefully careless (to borrow Robert Maxwell’s phrase) composition of disjointed office buildings, grp-clad and systematically striped pavilions that Stirling would later compare to two badly-parked London buses.

This particular evening he had been studying the pedestrian path through Stuttgart’s cylindrical drum, another ramping pathway in the making. His usual method was to work over the office drawings, making a series of small-scale overlay sketches. I suppose we must have been making too much chatter, while, down at his end of the table, he was trying to concentrate. We had worked our way through questions of architectural invention and academic quotation. We were just now moving onto consideration of our top ten Frank Lloyd Wright buildings of all time, with Johnson Wax coming out on top for me, when Jim called a halt. He held up his page of intensely active drawings, showing us that he had noted down each topic of our discussion, adding his own closing instruction, pleading for some peace and quiet, which he then read out slowly and in a loud voice, ‘…end of conversation!’ When I look today at that much-published sketch, it brings me back to the close confinement and camaraderie of those basement days.

At that time, over the preceding seven years, Stirling had not had a single new commission leading to a built building, not since he was appointed to design that extraordinary little Olivetti extension in 1969. No wonder some people found him a little melancholy and sometimes brusque. Yet, despite this lack of client confidence and without any commercial success, he remained critically regarded, not just by friends in London and followers in Dublin, but in every corner of the connected culture, as the greatest architect in the world. The breakthrough burst of early work, four closely consecutive and individually brilliant university buildings, from Leicester through to St Andrews and on to Cambridge and Oxford, had been completed in just eight years between 1963 and 1971. He had been a visiting professor at Yale since 1968. The black book, published in Germany in 1974, charted the flow of his creativity across those lost years, almost a decade of ground-breaking work that never made it to construction, from Dorman Long through Olivetti Milton Keynes to Derby Civic Centre and St Andrews Arts Centre. And then, following that elegant publication, came a sequence of German competitions, first Dusseldorf, then Cologne and, at last, in 1977, the career-reviving scheme for the Neue Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

It had been a slow climb back to building and times had been tough. Two phases of social housing at Runcorn, both now long since demolished, had kept the office open for ten years from 1967 to 1977. The office of James Stirling and Partner, soon to be Stirling Wilford and Associates, effectively started again after the Stuttgart win.

I wasn’t much involved in the development of the early stages of the Stuttgart competition entry, helping out in only a minor way during the final draw-up. This was led by Ueli Schaad, a fluent designer and a tirelessly fast worker. Ueli could produce several sketch schemes from scratch in a single morning. He was supported by Russell Bevington, who was trusted by Stirling and a leading figure in the studio. He had made all the ‘after-drawings’ for publication on Dusseldorf and Cologne and was finishing these fine drawings when I joined the office.

The project concept had been developed from one short and simple instruction issued before Stirling disappeared on summer holiday: ‘Make it a Dusseldorf mark 2’. So, by this diktat, before the emergence of any new thoughts specific to the project in hand, there was going to have to be a circular courtyard, a mid-block pedestrian path, a curved glazed lobby and a top-lit gallery sequence.

Two books were often lying open on the trestle tables during those days. The Dortmund catalogue on German neo-classicism that Jim had brought back from Germany for further study. He was interested in Friedrich Weinbrenner’s evocative elevation drawings with their water-stained stonework. The other book was the newly published paperback of Norberg Schulz’s Meaning in Western Architecture, not Jim’s copy, my copy, but a topic of collective discussion and shared exchange between the competition team. I remember an aerial axonometric of Palestrina being borrowed as a useful reference point for the U-shaped gallery plan and terraced landscape arrangement for the Staatsgalerie extension. The ruined remains of Palestrina itself, visited many years later, proved to be an underwhelming disappointment, much anticipated in advance but somewhat stripped of their expected impact when experienced in reality.

A few of us had been laid off after the competition submission deadline, since there was no more work for us to do in London. As it happened, Sheila, my girlfriend, now my wife and partner, was laid off the very same day, work having dried up at her job with Spence and Webster. So we set off for Rome in Ueli Schaad’s VW beetle. Werner Kreis, who had worked in the office from ‘71 to ‘75 had recently taken up a teaching post in the studios at Kingston, so he was free to join the summertime trip. And, in Rome, we met up with Alfred Munkenbeck, a young American who had been working in the basement on a competition in Algiers. Werner was highly respected by Stirling, not only because he knew so much about architecture, but also because he was so fast at drawing. It was often a deciding question when considering candidates coming in for competition draw-ups: ‘Is he fast?’. No one was as fast as Werner, or as it happens, as sophisticated. On this trip, travelling down through Switzerland, he introduced us to the new work in the Ticino, Terragni in Como, the birthplace of Borromini, as well as to spaghetti alle vongole, the Pantheon and the whole panoply of the Roman baroque. One day, coming back into Rome after an outing to the Villa d’Este, Ueli went into the post office to call the office. Stirling was cross. ‘Where the hell are you. We’ve won Stuttgart, what are you doing in Rome.’ Ueli reminded him that we’d been fired. ‘Well, get back here immediately!’ We came back straightaway, me to resume my desk in Stirling’s basement and Sheila to start into her master’s at the RCA.

As soon as the office was reassembled, the Stuttgart clients had to be reassured by a studio visit. They needed to know that the London office was capable of carrying out such a large building. On the day of their visit, various friends and colleagues were borrowed to fill up the desks and told to look busy. Jim led a tour of the basement. He stopped at my desk to introduce me to one of the gallery directors, saying: ‘John’s one of our senior architects. How long is it you are with us now John, seven or eight years it must be!’ – then quickly moving on before they could question the youth or uncover the inexperience of this long-haired recently-graduated non-German speaking student type.

With the competition win confirmed, Stirling put a call through to Arup, inviting them to take on the structure and service engineering for the project. It was big project by any standards and the response was immediate and enthusiastic: ‘We’ll send around the A-team’. Arup had recently completed Piano and Rogers’ Centre Pompidou, the so-called Beaubourg, in Paris; radical, heroic, magnificent, but utterly different in every respect to what was intended for Stuttgart. I vividly recall the tone of that first meeting with the services engineers. Sitting around a big table in the basement, they challenged every principle of the design, explaining that the services concept, ducts buried in the wall thickness, daylight coming in through rooflights, was not the efficient way to work with a gallery project nowadays, not since the building of the Beaubourg. The structure was neither practical nor straightforward. Too many transfer structures.

I was amazed that Stirling sat calmly and quietly through the meeting, impassively keeping his cool, not questioning their attitude, politely thanking them for their prompt attendance. As soon as they had gone, he picked up the phone, spoke again to his original contact at Arup and asked one memorable question: ‘Could you send us around the B team?’ After that, all went smoothly on the engineering front and the Stuttgart scheme proceeded substantially as planned. I learned so much from episodes like this, how to hold fast to your own way of working and not allow yourself to be buffeted off course. Tenacity is a hallmark of the architect in practice.

My real engagement with Stuttgart began at this stage, working for two years with a growing team on design development and detail studies, until the work eventually moved on, with a new team, to the site office in Stuttgart. It was a complex multi-functional building and a labour-intensive set of drawings. We were joined by Shinichi Tomoe, a serious-minded man from Japan, newly borrowed from Colquhoun and Miller. John Cannon was brought in from Evans and Shalev, the only one of us with any real experience in working drawings. Chris MacDonald, a recent student of Crispin Osborne’s at the AA and also a fast drawer, joined the office for a few months. The core team soon expanded to include Ueli’s twin brother Peter and Alfred Munkenbeck. Each set of 1:50 floorplans was divided between five large sheets of tracing paper. The main plan being quartered at the cross-axes of the central drum, with the adjoining theatre block added on one long sheet to the side. We were all drawing in pencil with Mayline parallel straightedge drafting bars. We had to attach aluminium spiral rolls to the bottom edge of our drawing boards, allowing us to stretch over the boards without crushing the long drawings.

The culture changed from free-ranging short-span competition deadlines to one of slow steady work, a painstaking production of working drawings and learning from first principles about German building regulations. It was a long jump from the established language of Stirling’s architecture to understanding the technical demands of European construction. Ever since Leicester, ship’s railings were the office standard, thin tubular bars, horizontal in emphasis, or, for a more solid-seeming balustrade, a square section concrete extrusion could be suspended a little above the floor, then tiled all over. Such details are common to the line of buildings from Leicester to Olivetti. Stirling was not ready to change his mind on matters like this. The German regulations required a maximum spacing of 100 mm, a calculation deemed sufficient to prevent the passage of a baby’s head through any gap in the upstand below the one metre safe height. After a lot of soul-searching by the project team, the problem was simply solved, and by Stirling himself. Not diverging from the two-bar principle inherited from Le Corbusier, we were told to grow the diameter of the tubes until all regulatory requirements could be met. This was described as a pragmatic transition from ‘thin-man railings’ to ‘fat-man railings’. No compromise at all. Although, it has to be said, Corb’s railings were mostly white, sometimes black or grey, not pink and blue.

One tiny example of strategic compromise made an interesting lesson in survival, watching this son of a ship’s engineer navigate the choppy waters between idea and realisation. I was lucky to be a witness, to look and learn. As is well-known, the overall design was sprinkled, some might say laden-down, with quotations; pit-head contraptions for the public lift, a piano-shaped plan for the music school, two post-Leicester by-way-of-the-Beaubourg colour-coded up-ended pipes for the exhaust of extract fumes, a pile of tumbled-out ‘ruined’ stones for the carpark ventilation, Egyptian cornices on the sculpture terraces, a Weinbrenner portico sunken down steps in the sculpture court, etcetera. For some reason, out of all of this crowded landscape of conscious reference and playful inclusion, one element grated especially with the gallery directors; a serried row of ‘gothic’ pointed arched windows, stepping along under the external ramp that encircled the sculpture court. And yet, for no clearly stated reason, Stirling doggedly held on to them, re-presenting them for consideration time and again, as if they mattered in some mysterious way to the authorship of the project. Nobody in the office was keen on these arches either. Then, at a certain moment, quite late in the day, a concession was offered. The arches could be rounded, perhaps more Romanesque than Gothic, if that would help to ease the director’s mind. The concession was gratefully acknowledged as a generous gesture from architect to client. So, while everything else sailed through unnoticed, or at least unchallenged, the whole paraphernalia of personal shapes and unnecessary gestures, this one contested topic had worked to keep them distracted. And now, a single and seemingly hard-won compromise, craftily substituting one shape for another, sufficed to keep them happy.

Up Views

Above my desk in the basement bow-window, one floor below Jim’s desk upstairs, hung the framed original of the little worm’s-eye view of the Florey building, a particularly fine-line ink drawing, and a particular favourite of mine. I believe it was one of the new drawings Leon Krier made for inclusion in the black book, one of many special drawings he drew, or re-drew, for that landmark publication. That famous axonometric projection, not yet coloured up — that phase came later — had featured on the cover of the catalogue from the James Stirling drawings exhibition at the RIBA Heinz Gallery in 1974. It did not form part of the original set of publication material for the building completed in 1971. In this sense, as a new Choisy-style drawing in the old Stirling style, it was more of an ‘after-after drawing’ than the usual ‘after-drawings’, more Stirling than Stirling himself. After-drawings were made partly for publication purposes, partly to ‘fix’ the design. They were made in the aftermath, part of the routine in the wind-down days following a competition entry or during the post-completion period of a building, made to capture some crucial aspects of the form, to illustrate the conceptual structure or, perhaps, to clarify the complexities of a circulation pattern.

Presentation drawings were set up precisely, first in accurately drawn pencil underlay and then traced off using a studied selection of .18 and .13 Rotring pen. The thicker line weight of a .25 nib might be sometimes sparingly allowed, for instance to emphasise a section line, but this was best avoided. This was a demanding skill, requiring grease-free page preparation and a steady hand. Lines had to join exactly at the corners, with no crossed lines or variations in thickness. The pen had to be held vertically. You must never let the nib lean into the bevelled edge of your adjustable setsquare. Curved lines, whether drawn along French curves or set out with a compass, had to seamlessly connect with straight lines with no trace of the point of transition. When mistakes were made, as they must be from time to time, the ink-line had to scratched off the surface of the page with a razor blade, then the surface made perfectly smooth by rubbing with an eraser or polished with the back of your fingernail, then the new line added back exactly in its place with no visible evidence of repair work. This was a question of honour among the aficionados of the architectural forum. It was important to keep the drawing clean and dry, no sweaty hands, including the risk of damage from the large hands of the big man himself.

I had arrived in the office assuming I knew how to draw. After all, I had studiously modelled my student drawings on Stirling’s drawing style. I knew the sources. I knew the regulating lines of early Corbusier elevations. I was steeped in the graphic culture of Russian constructivism. I thought I knew what I was doing. But I soon found I could not compete with the intimidating speed of the real experts in the field of Rotring inkwork. In these elevated circles, I simply wasn’t fast enough. I could crawl with confidence, but I couldn’t run.

At least my UCD training had equipped me with the necessary skills in pencil draftsmanship. We’d had a number of American-educated tutors at UCD, men who had worked and studied with Mies and Kahn. Cathal O’Neill, Jim Murphy and Shane De Blacam had shown us how to draw in pencil. From them we learned the tricks of the trade, how to rotate the pencil as you draw to keep a sharp and unvarying line, how to work your way down the page – always moving from right to left – in order to keep the drawing from getting dirty, when to change the lead in your clutch pencil from F to H to allow for changes in humidity as the day wore on into evening. And this training proved to be an effective and useful preparation for the Stirling office culture.

All the Stuttgart working drawings were drawn in pencil on heavy tracing paper, then stencilled up in ink with dimension lines added and the bare minimum of descriptive text. A basic list of German / English technical terms was pinned up in the studio so that we could label the drawings consistently if not completely correctly; eingang / entrance, schnitt / section. Those of us with limited language skills soon picked up a superficial fluency in keyword German, sufficient to allow us stencil a very limited number of disconnected words, free of any burdening concerns about grammatical context.

In addition to contributing to the coordination of structure and services, drawing duties were shared out collaboratively between the basement brigade. The whole series of 1:50 scale drawings – plans, sections and elevations – was a collective enterprise. Over that two year period, any one drawing would have been worked on by four or five people. Within the larger enterprise, we each took, or were given, individual responsibility for certain small-scale and secondary aspects of the project. I remember Shinichi Tomoe straining over the precise placement of those seemingly casually-strewn ruined stones, trying his best to make it look as if they had been blown out of the wall and onto the grass along Konrad Adenauerstrasse. I worked for quite a while on the detailed design and setting out of the Le Corbusier-at-Weissenhof influenced Archive building; controlling its curvilinear geometry, refining its columnar frame and developing its spiral stairs. The Archive building was my training ground.

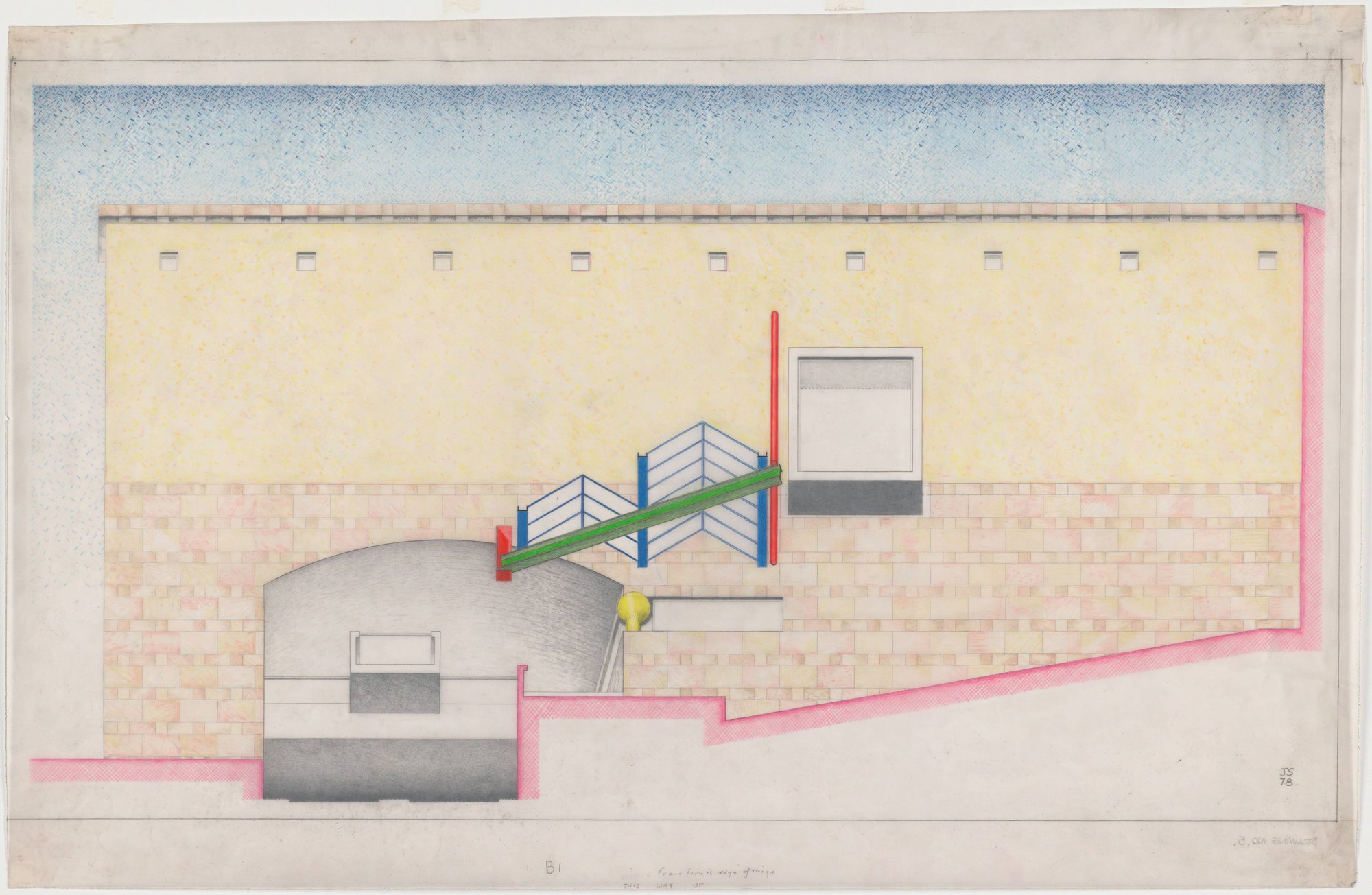

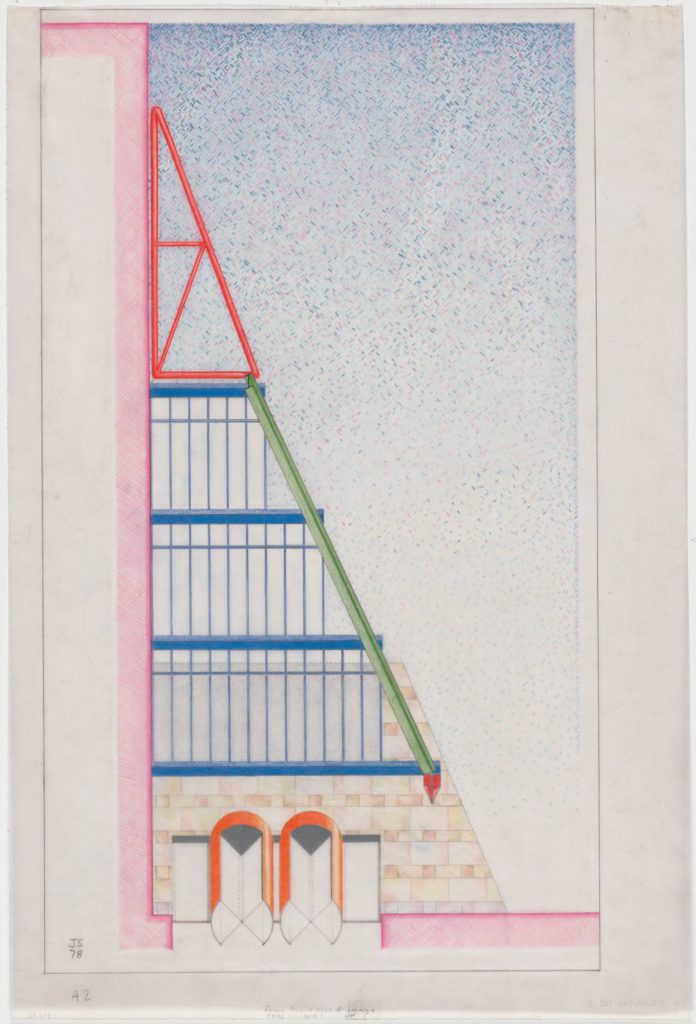

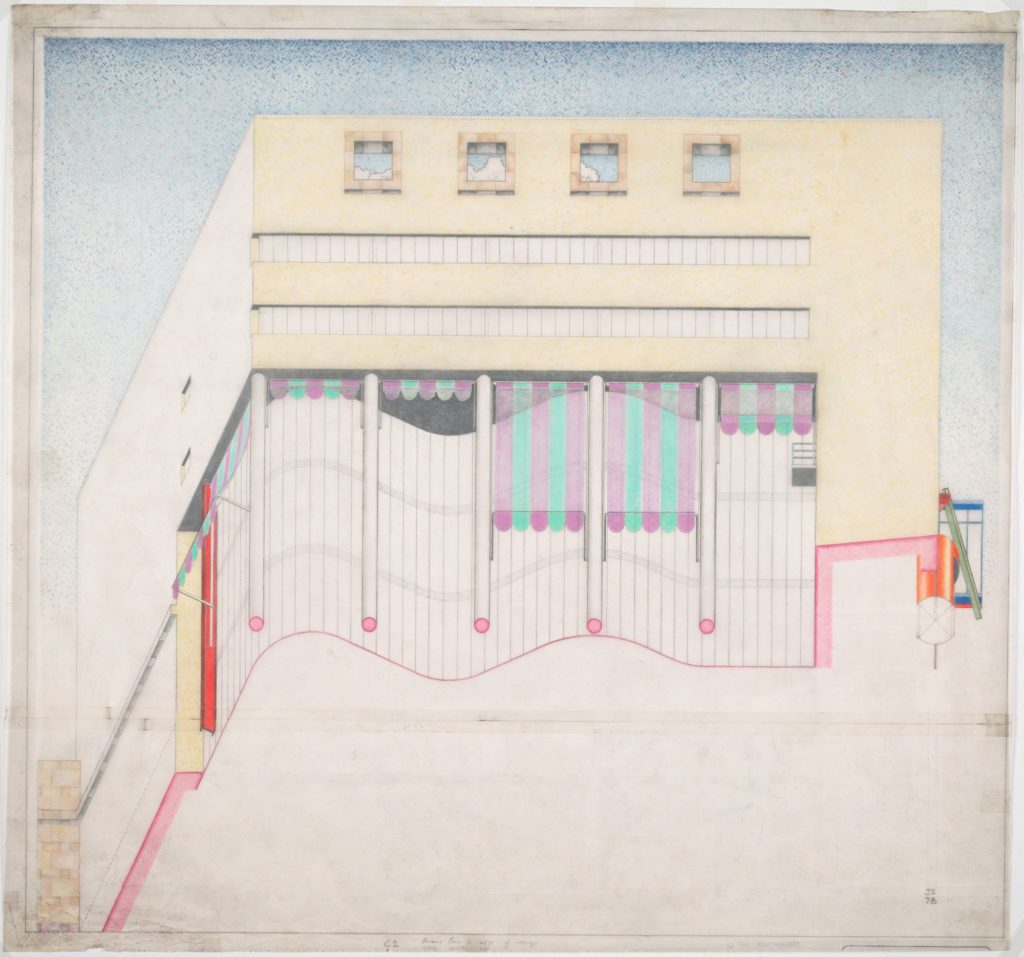

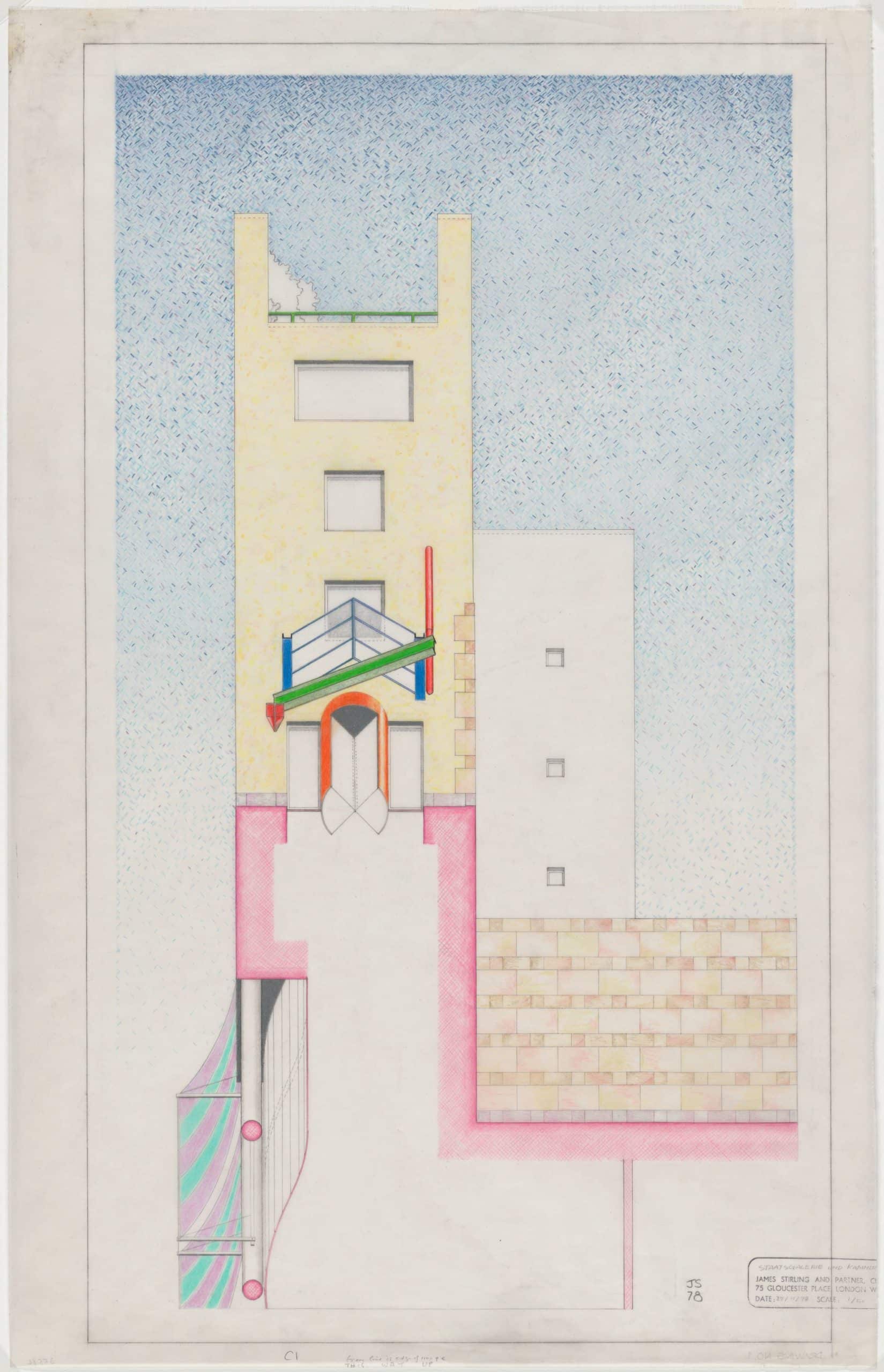

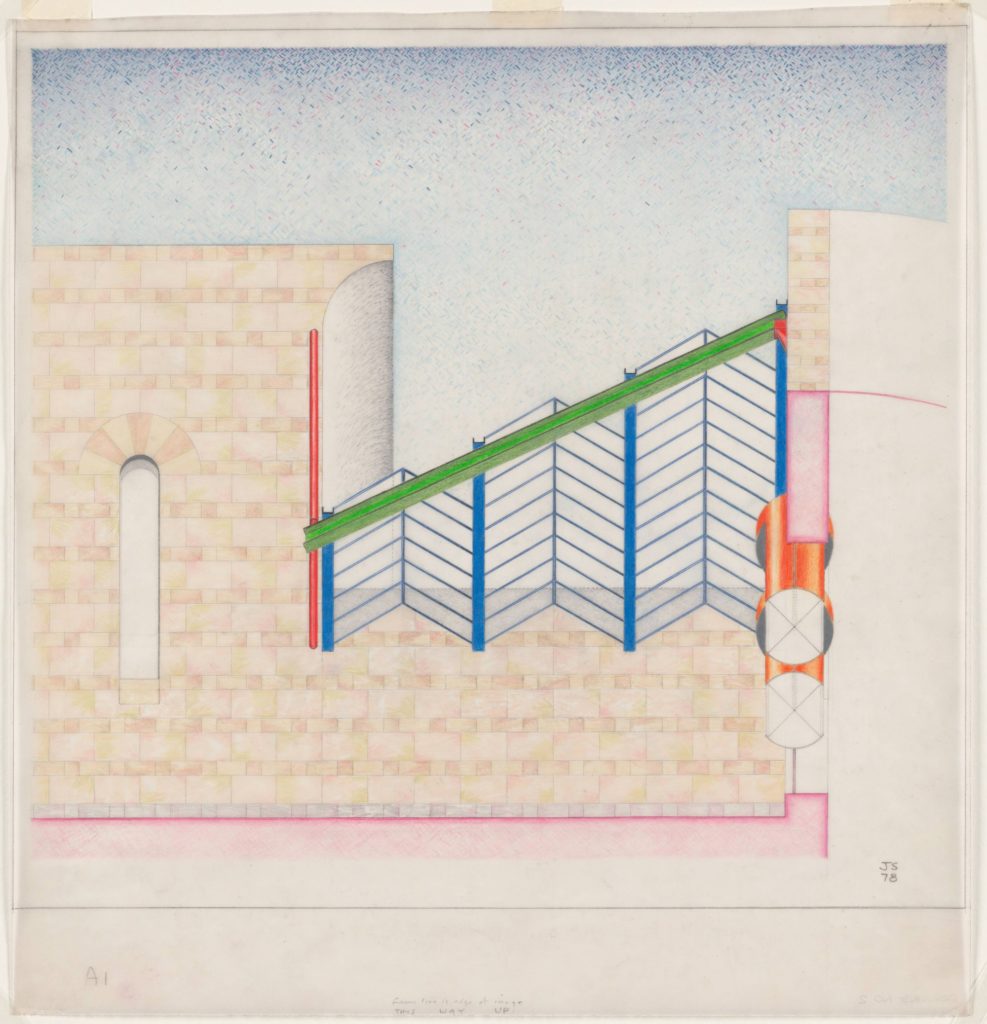

One particular part of my work became the resolution of the steel and glass canopies, a family of industrial elements, like railway station structures, overhanging each of the public entry points to the building. Each canopy had its own relationship with the surrounding stone-clad or rendered elevation. The common compositional principle was an unsettled balance between a triangulated tubular steel truss, a diagonally underslung H-section steel beam that lands on a wall-mounted bracket, and a varied array of one, two or three pitched glazed roofs. These elements had to support each other, or be suspended from each other, and if they were not supposed to make objective structural sense, they had to have some semblance of rigour, an internal consistency of connection, to unite them within the visual language of the project. This became my task.

Alan Colquhoun had been a travelling companion of the young Stirling. They went together in the 1950s to visit the new Le Corbusier buildings, buildings which were to become the subjects of Stirling’s first published essays: From Garches to Jaoul and Ronchamp and the crisis of rationalism. He was forever an unforgiving critic and Stirling was not to be spared for old times’ sake. Here, extracted from a wide-ranging review published in the AR, a special edition to mark the significance of the newly-completed Staatsgalerie, is what Colquhoun had to say about those canopies.

Metal and glass canopies are a leitmotif in the building and occur over all entrances. In a curious inversion (which increases the sense of quotation) these ‘High-Tech’ elements play a purely decorative role and are stretched like a filigree over the stone surfaces. They are all asymmetrical and highly mannered and are sometimes used to overcome awkward formal problems as at the main entrance and at the entrance to the theatre. These canopies with their primary colours – and also the brightly coloured window frames, hand rails to the ramps and trim throughout the building – are the least convincing part of the design. They detract from the admirably rich texture and colour of the stone facing, and have an early 1970s’ pop-tech quality which is slightly dated. Perhaps in these canopies Stirling is aiming at the Modern equivalent of Classical ornament. But it is interesting that he has to give this a functional justification; there is no place within the vocabulary of modern architecture for ornament of a purely conventional or metaphorical kind. [1]

Stern stuff from an old friend. Honest and clear criticism, disapproving though it may be.

Back in the late summer of 1978, long before Colquhoun’s theoretical anxieties, (to borrow Rafael Moneo’s phrase), I was struggling to make sense of these same ‘awkward’ elements, to structure the components of their assembly. The single-bay freestanding steel and glass portico had been a central part of the original scheme, marking the way up from the carpark on Konrad Adenauerstrasse. Another three-bay lean-to had been sketched in position over the main entrance on the competition drawings, but not much worked on since. Now there were to be three lean-to’s, one for each way in to the building. Stirling was out of town and I had to make a start.

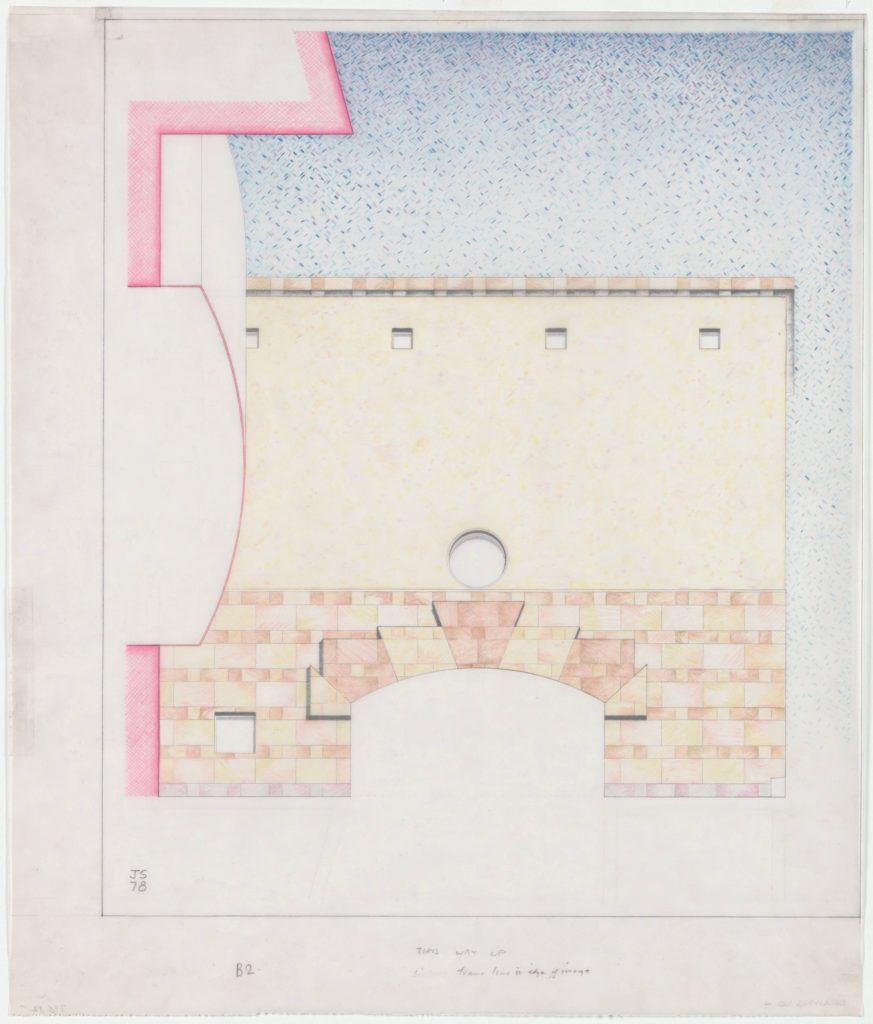

I began drawing them from underneath. Looking from this point of view provided a way of charting their common characteristics, seeking a formal coherence, something that described the inner shape of the structures, a shape that couldn’t be properly described in plan or section. I suppose I thought I was working in the office tradition, something like the Florey worms-eye that I looked at every day. The first drawing was of the main entrance.

The zoomed-in drawing soon extended itself beyond the immediate confines of the mechanical contraption to include some of the surrounding context. So, quite quickly, this supposedly technical drawing, from being a simple working drawing study, became a compositional exercise in itself, with the adjacent round-headed window on the left-hand side, the curved cornice above, the sweep of the entrance hall to the right, and then the addition of the stonework pattern to pull the whole picture together. A second drawing followed, another planar projection of the same arrangement, this time at 90 degrees to the original. This one formed a triangular composition, from the apex of the tubular truss down to the baseline of the entrance hall façade. I can see now that I was held back by my own lack of technical knowledge from much further development, for instance with any attempt at convincing fixing details. The drawings are large-scale design studies, confirming geometrical strategies and stripping back the elements, as if to abstract the crucial points of confluence between these spindly structures and the space they sheltered. One more projection was soon underway, examining the long façade of the archive building on Urbanstrasse. This drawing focused on the undercroft soffit, with its recessed curvilinear gazed screen and the roof-garden windows terminating the structural axis of four circular columns in an open view of the sky.

Three A1 drawings were well underway and all spread out on my desk, representing several days concentrated work, when Stirling suddenly appeared in the office, back from wherever he had been, maybe teaching at Yale. He was in a testy and impatient mood. He wanted to know why I was spending time on these big drawings. They didn’t look much like working drawings, not much practical use given the pressing deadlines. We needed to be working effectively to get the bloody working drawings done and ready for German approval. I thought I’d better keep low and stay out of trouble.

He took one of the drawings, the first study of the entrance canopy, away with him. Later that day he called me upstairs. ‘Nice drawings actually, how many have we got?’ Three, I replied. ‘Do think you could make three more – you see, I think MoMa want a set of six, actually.’

I looked over his shoulder, at his own drawing desk. He had begun what would turn out to be a tediously slow sky-colouring process, using blue and purple Derwent pencils in a graded sort of cross-hatching. This was a new departure. Interesting. And I was out of trouble.

Descending downstairs, I reported to Shin and Alf that we needed three more drawings, needed them in a hurry. One each. Shin made the vertical view of the Archive entrance. Alf worked up one of the Theatre drawings. Now we had six. And it looked like a set. I don’t remember how long Stirling spent colouring them in. He sat upstairs at his desk for days, listening to radio 3, happy in his work.

He habitually carried a blue colouring pencil on his office prowl, usually a well-worn Derwent. Likewise he kept a red pen close at hand, usually a plain old Bic biro. The red biro he used to mark-up sketches and option studies. Sometimes simply a little red tick of approval – it’s safe to continue along these lines. Sometimes he provided little scribbled notes – indications of how to direct the next move. The blue pencil he used for the so-called ‘blueing in’, a selective graphic emphasis, hand-coloured onto dyeline prints, usually the night before a submission deadline. He wanted to emphasise what he considered to be the significant walls in a plan. Not necessarily those with a structural purpose or any practical priority. More the space-enclosing planes that reinforced the conceptual structure of the scheme. Stirling reserved this task to himself. He was no longer involved in the hard-line draw-up, long since disengaged from the craft of ink on tracing paper, but he remained heavily involved in the completion of the final drawings. So, this is to say, there was an already established precedent for taking dyeline prints forward into the colouring-in stage.

The new thing now in process was the addition of layers of colour onto the tracing paper itself, to work the surface of an original line drawing beyond the confines of its spare lineaments. Line drawings imply no surface, as if there was no material support for those gravity-free lines drawn in abstract space. Once he started revisiting the black ink drawings, colouring in the sky on the Florey worm’s-eye for instance, something was sacrificed from the floating world of the original.

But these Stuttgart drawings were not problematical in this respect. The coloured-up drawings brilliantly developed the conceptual origins of the project. The Stuttgart scheme is not made of lines in space. It is not activated in section, unlike Stirling’s early projects. It is a terraced landscape, a stone-clad geology cut back in to the hill, with no essential transparency between inside an out. The walls are solid surfaces, pushed back in planes to surround the set-back levels. The only volume is the cylindrical drum. The Dusseldorf drum was a scooped-out space, powerful in plan but not yet present in its profile. The Stuttgart drum had started out in the Dusseldorf way, in Ueli Schaad’s first sketch plans, following the stated instruction to make a ‘mark 2’. Then Stirling, in his typical way, surprised the team by giving this drum a more definite vertical dimension, erupting out of the plan into sculptural space. A weed-topped Roman ruin lodged at the centre of the project.

In their pencil outline state, the planar projections were a half-formed thing. Neither working drawing nor art-work. He took them and changed them completely, by applying an impressionistic rendering of stone texture, fading skies and a few bright colours; red truss and wall bracket, green beam, blue channels, orange revolving doors and, just once, to mark the theatre corner window, a yellow mushroom-headed column. In the finished building, steel U channels and H beams are combined together in a uniform blue. The windows are green in the actual building, shown as pencil grey on the drawings. I guess that the German office needed to set up a hierarchy between structure, support and frame, a rationale that wasn’t required on the London design drawings.

When the work was done, with the six drawings finished and all coloured up, he called me upstairs again. This time with a question. ‘How would you describe these drawings?’ Well, I supposed, they could be described as worm’s eye planar axonometrics. ‘Hhmm… I was thinking of up-view full frontals, what do you think!’

It is said that there had been seventeen schemes of alternating colours offered to the planning authority to provide the intended contrast between adjoining grp panels in Olivetti Haslemere. The initial proposal was violet and lime green. Colour-cautious planners are held to blame for the eventual low-key solution of mushroom and cream. The violet and lime green combination turned up once again on these up-views, this time on the blinds of the Archive building.

Colour was important to Stirling, not in the usual tasteful way, neither soft nor sensitive, more a flash of contrariness, like a sign of life, or a spice of life. He wore purple socks that livened up the ankle-space between his grey flannel trousers and his desert boots. Every day. He wore blue cotton shirts and spotted knitted ties. Every day the same. Relentless. Once when he went on the usual family summer holiday to Normandy, he asked Sheila and me to move in to Belsize Park to look after the house while they were away. His wardrobe was neatly shelved in stacks of identical shirts. His spotted ties hung in rows. No surprises there.

He liked to offset the sensible with the surprising. The green flooring in Stuttgart was a surprise to most of us. We might have expected a stone floor in the hall of such a stone-covered public building. It’s not as if there was any shortage of stone in this building. On the contrary. He looked for a contrast to cut through the staid consistency, like mustard in a sandwich, a populist gesture to prevent the building being misunderstood. ‘These colourful elements counteract the possible appearance of a monumental stone quarry.’

One further anecdote about colour. When Stuttgart moved off to site, I worked with Peter Schaad on the competition for the Wissenschaftszentrum, Berlin. Following a few false starts, Stirling having cleared our self-evidently rational office-block arrangements out of the way, the project quickly took shape in the form of a cluster of plan-type configurations. The collage strategy helped us to integrate three or four new blocks with the existing building on the site. And the far-from-arbitrary ‘carefully careless’ plan composition sweetly resolved what could have become a complicated site geometry, especially given the repetitive cellular content of the think-tank programme. It all seemed to being going, as they say, according to plan, with the type-plans easily extruded upwards into building blocks of differing height, until we broke up for the Christmas holiday. Jim took the work-in-progress drawings with him to think about the project from home. On our return in the new year, we were presented with a full set of overlay elevations, sketched out in felt pen on A4 tracing paper, with a shocking pyjama-pattern of pink and blue storey-height stripes.

I don’t know what we might have expected, but this wasn’t it. Looking back now, in rear-view hindsight, we shouldn’t have been at all surprised. This was nothing new. It was simply a horizontalised reprise of the same vertical pattern that had been superimposed on the Olivetti elevations, ten years ago. But, by that time, in 1979, there was nobody left in the office, apart from Jim and Michael, who had any involvement with the Haslemere project. The energy in the office came from Stirling’s restless spirit, a maverick virtuoso, an original minded-artist who remained ready to start again from a new position or selectively revisit his repertoire without stagnation – one who could reinvent old ideas in ever-surprising ways. I once attended a lecture, the standard format, a scrupulously edited slideshow with his cards held close to his chest, what he called his lecture type 1. As opposed to lecture type 2, which was the more unusual event, where he set out to explain what was actually on his mind. On this occasion, someone in the audience asked a question at the end of the talk. Not the usual question asking why had he changed his style, was he now a post-modernist, what were we to make of this new work? This person wanted to know whether, given how many different projects he had designed over so many years, did he not agree that careful analysis would reveal that he’d had only five ideas across his lengthy career. He wasn’t much taken aback, as I recall. He thought for a moment before he replied: ‘Only five ideas, well, I suppose that’s three more than Mies – and five more than Gropius!’

In July 1984 we interrupted, no, extended, our honeymoon in Venice, taking the train to Stuttgart to join an office party in celebration of the opening of the Neue Staatsgalerie. Charles Jencks was there to see the building. We joined them for lunch in the gallery café. Jencks was teasing Stirling that the building looked unfinished. The drum lacked a dome. Jim was teasing Charles about the cumbersome lens on his camera. Male Jewellery. Later on we walked around while Jencks took his photos. A passing stranger stopped us on the stepped ramp, recognising the figure of the architect from pictures in the local newspaper. He shook hands with Stirling, saying in broken English how beautiful was the building. Jim was more than pleased. Shy. Proud. He turned to me and said ‘There must be something wrong with it John, everybody seems to like it!’

All drawings © the estate of James Stirling.

Notes

- ‘Democratic Monument’, Architectural Review, December 1984