Gowan and Stirling

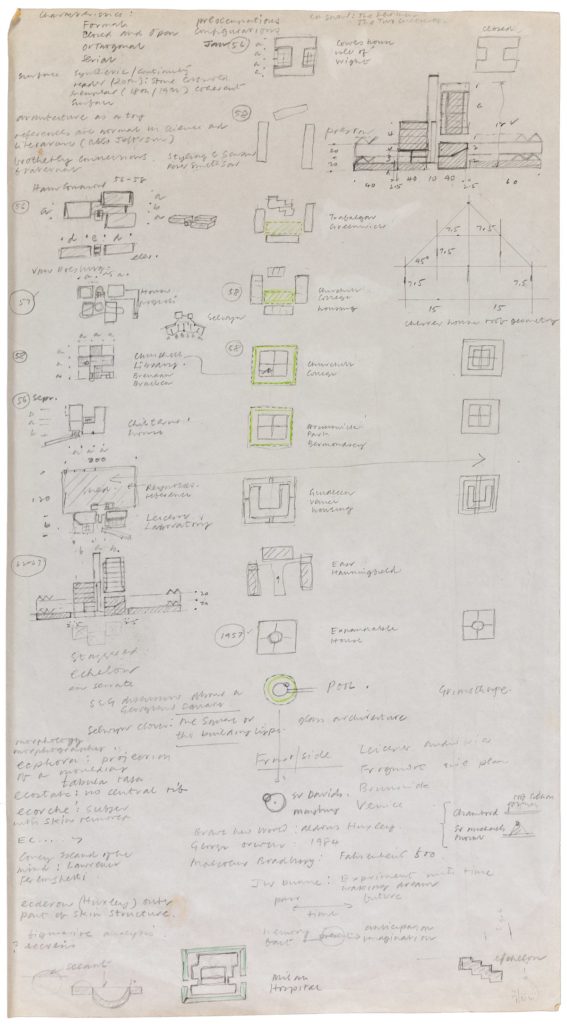

This odd-shaped, yellowed analysis drawing by James Gowan, drawn directly onto heavy paper isn’t dated, and was probably added to years after the drawing was nearly complete. Ellis Woodman describes the drawing as ‘that drawing that James always kept in the box with his sketchbooks’. Unusually, when I first saw it, we were in James’s studio on the first floor, in the airy piano nobile of his house. We would usually sit in the ground-floor sitting room, in the shallow bay window, people passing close beyond the thin curtain, outside on the Bayswater Road. We were upstairs on this occasion because he had been rooting through his plan chest looking for material for his upcoming book by Ellis.

I spotted the drawing, and asked what it was.

‘You’ve got a sharp eye.’

He explained it was an attempt to understand through an analysis of their work together where the fissure in the relationship with James Stirling might have begun. Over the years when we had occasionally met to discuss and gossip about various matters, and to go to lunch in latter years at the Pizza Express, he hardly touched on this still burning issue in the architectural culture of this country and beyond. I asked if I could take the drawing and have it copied.

‘Go to Sarkpoint,’ he instructed.

Once outside I thought I would go to a printers I knew near Bond Street Station on the Central Line, about ten minutes from Notting Hill Gate, rather than schlep all the way to Euston where Sarkpoint was located, in the middle of nowhere, a lengthy walk from any Underground station, thus saving time for more conversation back in Bayswater. The printers did a trial that was hopeless, and a second no better. I rang James.

‘I told you to go to Sarkpoint.’

I took a cab.

Sarkpoint was the best printer of architectural drawings, and the scene of considerable activity before the submission of major competitions; as practices rushed to get their entries well printed, the whole rogue group of London architects could be spotted there. There is a story, possibly apocryphal, of James Stirling turning up with his entry, only to find Richard Rogers ahead of him, waiting for his prints. He refused to unroll his drawings while Rogers was present, fearing perhaps that the rival might get a glimpse of his scheme, dump his own, rush back to his office and, in the remaining eight or nine hours, design and draw up a new entry and somehow get it printed.

After a conversation downstairs I was directed upstairs to where a solitary figure sat staring at a screen among the plethora of reprographic equipment. I showed him the drawing, a couple of goes and he had it perfect. As I paid on the way out I remarked, ‘He’s an artist.’

‘I’ve heard him called a lot things, but never that.’

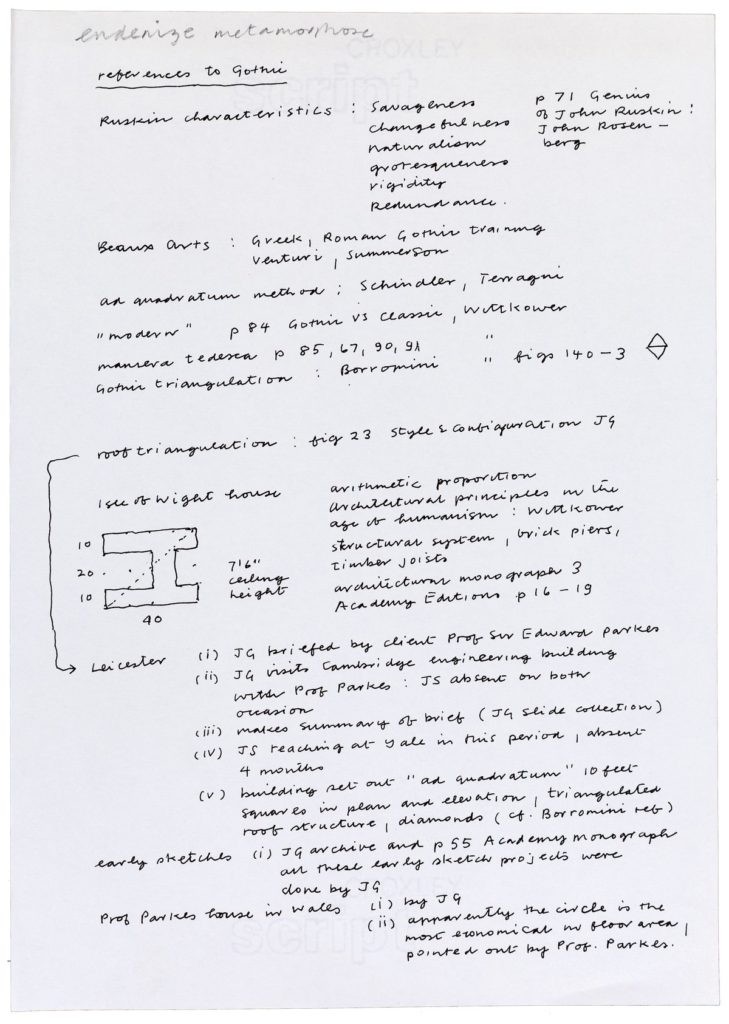

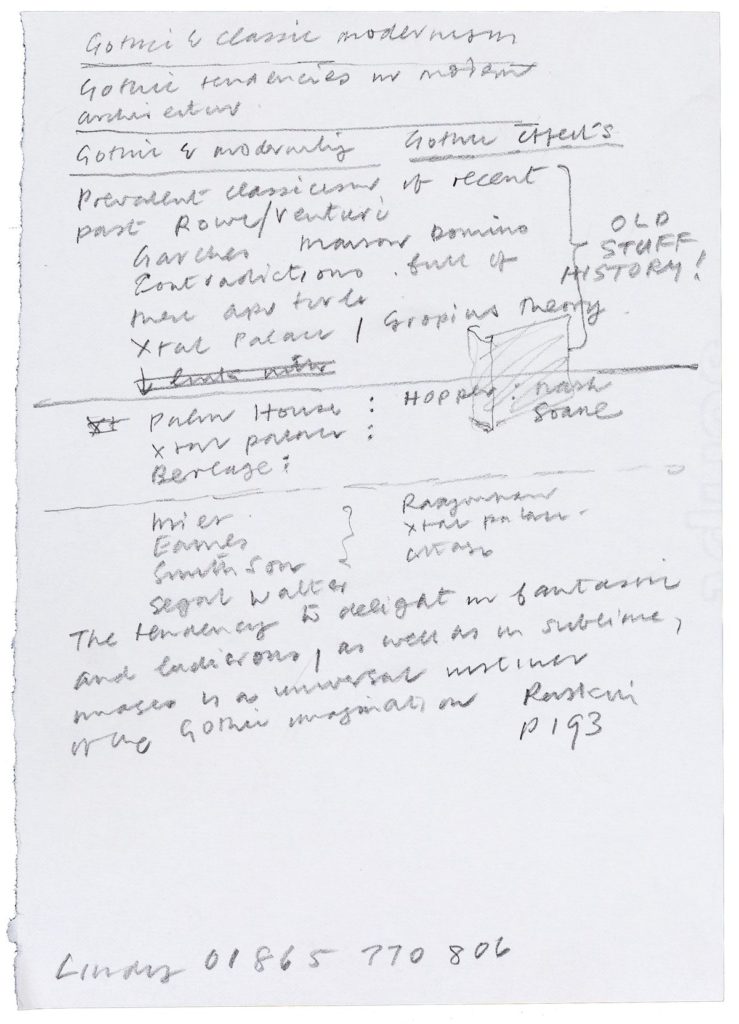

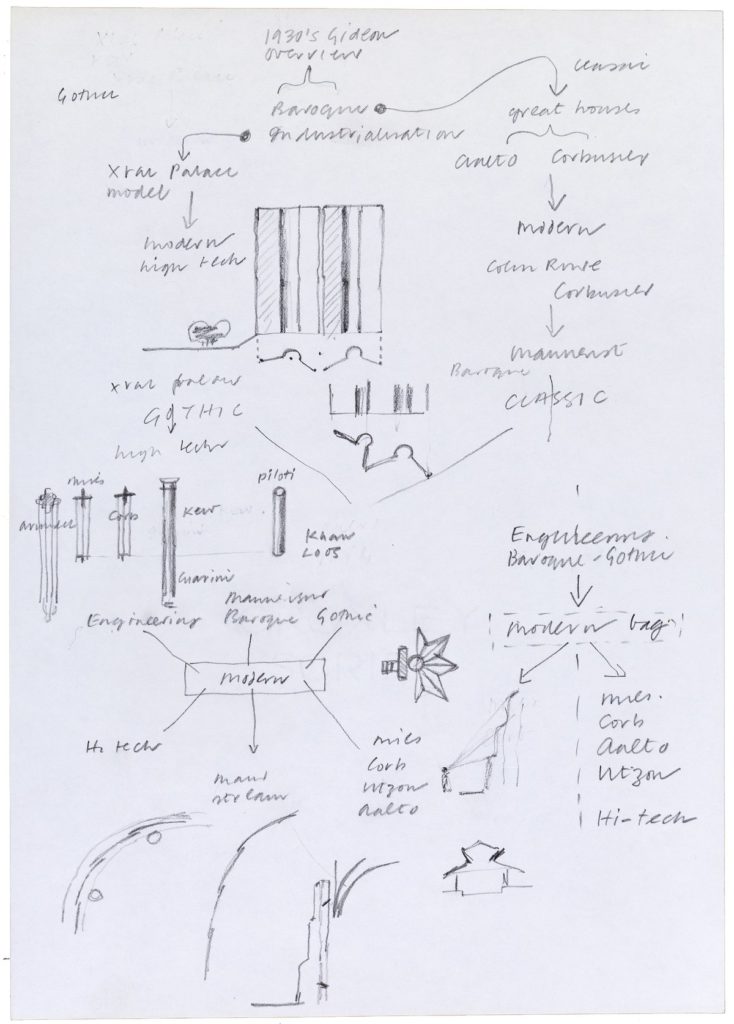

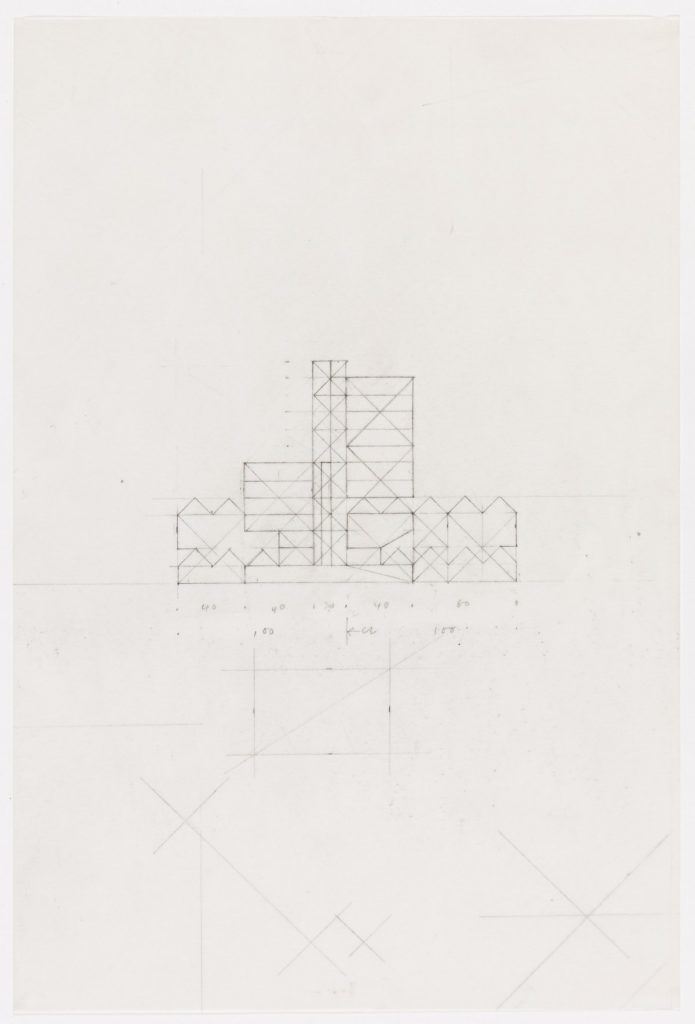

I have been trying to piece together the conversation James and I had when I returned. I’m sure he said that he began the drawing in order to better understand why the break-up had occurred. He had concluded – but I’m not sure when – that the division was perhaps inevitable because he was inclined to the Gothic and his partner was a Classicist. He discusses this with Ellis Woodman in Modernity and Re-invention (2008) in the section ‘Building Leicester’. Here the definition of Gothic is derived from Ruskin’s, in that it refers to ‘change and adaptability’. I forget the exact terms we used that afternoon to delineate the differences; I can remember his insistence that the diagonal was a characteristic of Gothic, and that it was made up of bays. But probably the central issue was the one of the Classical impulses to completion, with symmetry its major vehicle for these ends, compared with the Gothic sense of asymmetric assemblage and incompletion.

It is a question for another time, whether the Beaux Arts basis of the teaching at Liverpool was an increasing influence on Stirling’s later work. And one should remember James had a fondness for bifurcation, describing elsewhere in talking about the Hampstead house, that all buildings are variants of the ‘pavilion (open, extroverted, fashionable) and the castle (closed, secretive, timeless)’.

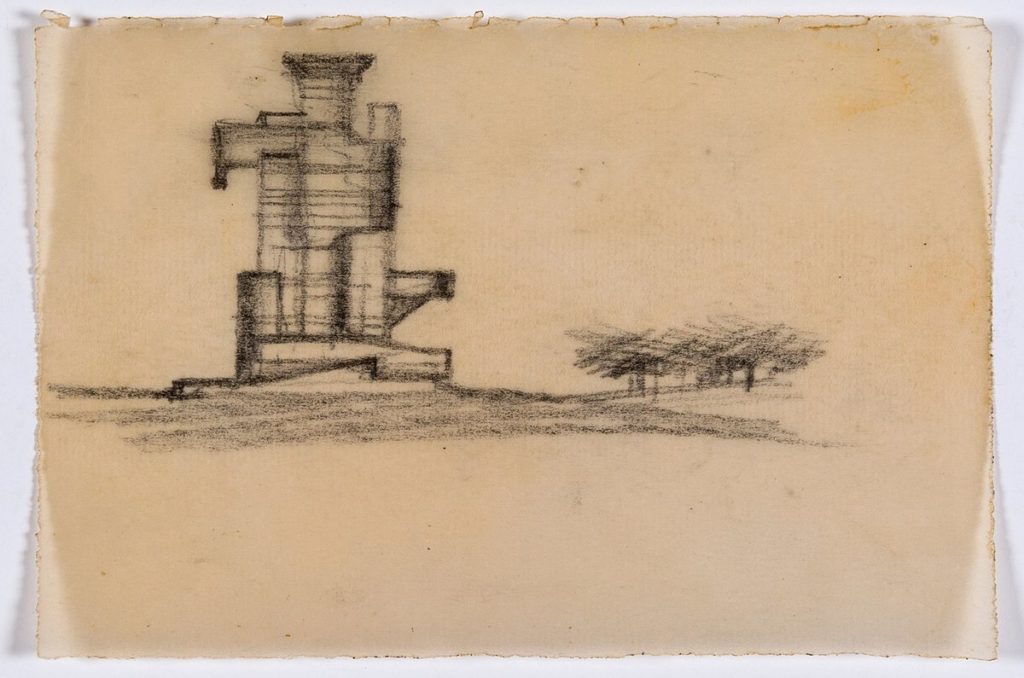

The analytical drawing itself is interesting for the inclusion of many literary references: 1984 by George Orwell, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley and Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451, all dystopias, and the books of C.P. Snow, one, The Two Cultures Cambridge, concerned with an increasing divide between science and the arts. James was always ready to affirm that for him the written word was more important than buildings, literature more important than architecture. There is another reference to J.W. Dunne’s Experiment with Time, with a neat analysis of the books contention that the present is a bridge between the fact and memory of the past and the future of anticipation and imagination. In addition there is a note of morphology and morphography, and of ‘ecorche, subject with skin removed’. The eclectic range of references indicate the breadth of his mind, and may contain a clue also to the strange Vitruvian figure made from pipe-work that stands in the foreground of his Palladian villa on a lake of 1977.

James said in one of our last conversations that the origins of his ex-partner’s famous affability was rooted in his dyslexia, which made it necessary for him to make friends to help with his homework when he was a schoolboy. It is said in a close relationship, if you are about to be cast off, you are the last to know, and if and when you do, it’s too late. The first intimation James had, was finding out that Stirling had taken Stephen Gardner to see Leicester without telling him first. After the break-up, Stirling opened a practice in Gloucester Place; Gowan retreated to his house, double fronted, blind-windowed and white stuccoed, just off the Bayswater Road. Big Jim’s office became, over the years, thought of as welcoming migrant talents and giving them their head. James worked with a series of assistants, usually recently out of the AA, and never more than one at a time. All remember how closely he watched their work.

There is perhaps a simpler explanation for the breakdown, that it was not just a clash of styles. It may have been the result of an imbalance of ambition. Ambition is thought of as a primary virtue, particularly with regard to an open society; but with regard to friendship, it is rather the eighth deadly sin, akin to, and the inverse of, jealousy. Of course practices break up, Allsop and Lyall, Farrell and Grimshaw, Team 4 – sometimes without rancour – but the Stirling Gowan split felt and still feels like more than an ending. It was also the initiation of a new age of British architecture, where the virtues of teamwork espoused in the 50’s were pushed aside by the emerging age of celebrity, in which the architect would need to be a star. The Royal Academy exhibition Foster, Rogers, Stirling in 1986 institutionalised this shift from the collective to the individual, reflecting changes occurring in the wider society at the same time. The role was one that Stirling, through his energy, courage and ability came to deserve and to relish.

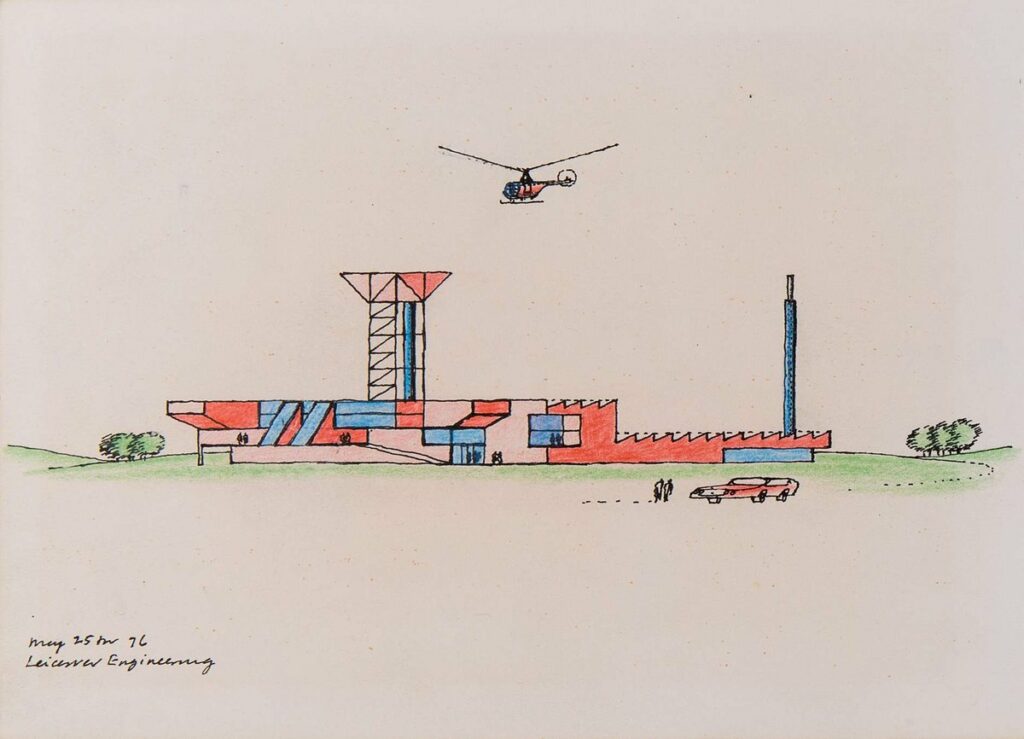

Neither of them ever did a building as epic as Leicester again, so one can say something was lost in the rupture. Gowan characterises the Engineering Building in the conversation with Ellis Woodman as ‘my Gothicism with Stirling hitting it with as much classicism as he can’ (James had derived the original schema while Jim was in America). Is this a clue to what was lost? Is it akin to Hawksmoor on his way back from Castle Howard picking up the job of restoring Beverly Minster, and complaining of having to deal with the despised Gothic? But Hawksmoor’s experience of working on the building transformed his attitude, and after this the marrying of the Gothic with his entrenched Classicism, the reconciliation of opposites, becomes the leitmotif for his later work, ending with the beautiful west towers of Westminster Abbey. What if the partnership had somehow survived? Was the splitting of these two opposite sensibilities also the scattering of the possibilities for a complex and subtle new architecture of reconciled antagonisms, of a lucid, critical, keenly perceptive mind as a bridle on the wild bucking the talent of the other, the best architectural mind and talent of the age in continuing stormy alliance for a while longer for the delight of us all.

The redrawing the Leicester building slightly larger and more precisely dimensioned at the top of the analytical drawing is a re-assertion of his contribution, the Gothic armature underlying the whole, drawn perhaps at a time when it was becoming not unusual for the building to be credited to Stirling alone. It is difficult to see in the rest of the diagrams a conclusive argument for the separation because of the Gothicism of one and the Classicism of the other. It is more likely that the analytical drawing was an attempt, over time, to rationalise again and again an ache that never entirely healed.