Tales from the Crypt

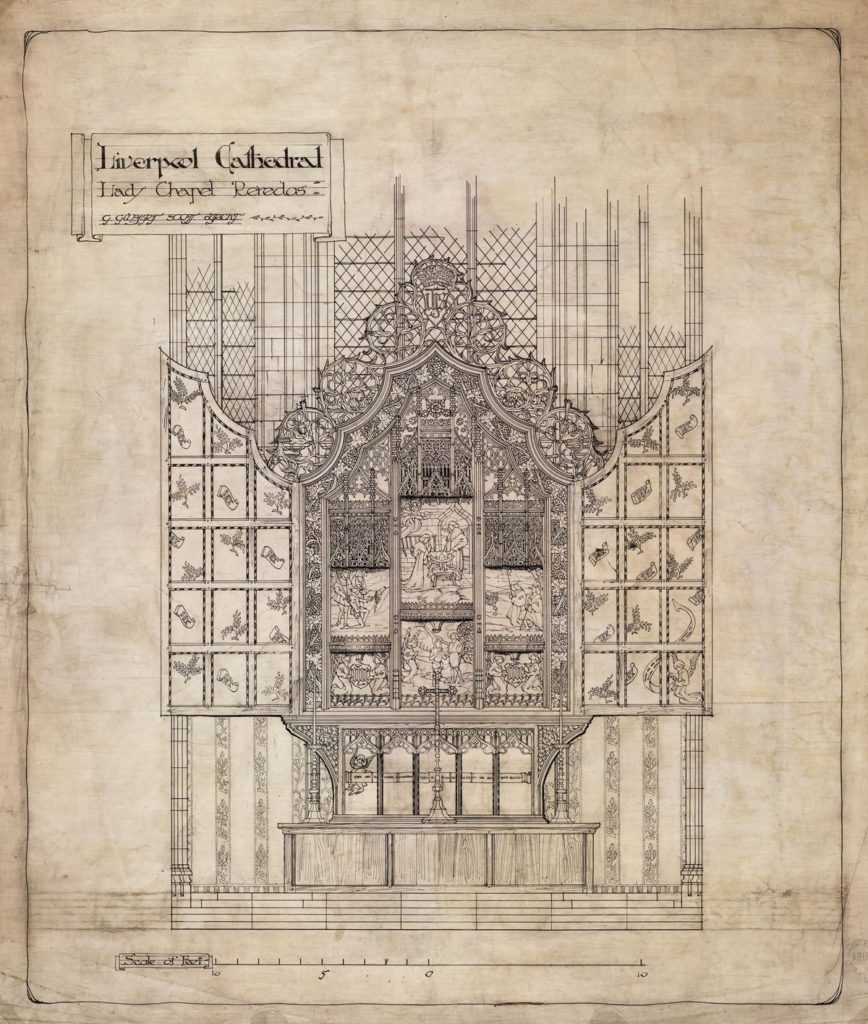

The great mysteries are not the invisible things, but the visible ones. And to me, it is a great and fascinating mystery that the same architect, Giles Gilbert Scott, designed one of the world’s most awe-inspiring large buildings and one of its most exquisite small ones: Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral and the General Post Office’s ‘K2’ telephone box.

I grew up in Liverpool and became familiar with the shiver of horror always caused by the sublime cathedral on its vertiginous mount above a macabre canyon of catacombs and monuments. There was a more obvious connection with death than the afterlife. Here you found the Huskisson Memorial, named for the local MP who was the first-ever victim of a train crash. Unfamiliar with speed, he had stuck his head out of the carriage window. And there was also John Foster Junior’s souvenir of his Grand Tour inspired by the Temple of Apollo at Bassae which, translated to Liverpool, became a mortuary chapel. More recently, a contemporary of mine from school, who had become a successful solicitor, threw himself off the Cathedral’s forbidding and dreadful tower.

And so I wonder if mortal thoughts were on Scott’s mind when he won the Royal Fine Art Commission’s 1924 competition for the design of the nation’s phone box. He had recently become a trustee of Sir John Soane’s Museum, itself a place whose single-most outstanding exhibit is Seti’s morbidly fascinating Sarcophagus, a container for a corpse. And in his design for the GPO, Scott was clearly inspired by Soane’s own mausoleum in the Old Church Yard of St Pancras’ church in London. The distinctive summit of the phone box with its composition of segments is a clear reference to the pendentives and tympana of the Mausoleum’s depressed dome.

I really don’t want to suggest that Scott was obsessed by death, even if Cambridge University Library looks like a provincial crematorium. But it’s an interesting backstory to K2 which, on the whole, represents connectivity, municipal worthiness, public service, helpful communications and vital signs rather than demise and decay. Although, ironically, since the Cellular Revolution of 1979, K2 has itself been in inevitable decline, preserved here and there only as derelict accidents or as a whim to amuse jaded tourists.

Has anybody born after 1985 ever used a phone box?

One day I will explain to my children that, when not at home, to make a phone call you had to find a K2 (if at all possible avoiding the ones which had been misidentified as urinals) and then perform a peculiar ritual with coins while speaking to an ‘operator’ pressing Button A and Button B. After some clunking and whirring, a connection might possibly be achieved.

Then in 1958, the arrival of Subscriber Trunk Dialling (unfortunately known as STD) pushed K2 tentatively towards the age of digital. The shiny, black mechanical telephone equipment was replaced by a smooth enamelled grey unit, perfectly redolent of mid-century modernisimo and all its spoiled optimism. And with a symmetry that Jung would have recognised as significant, this grey STD unit was designed by Douglas Scott, a Raymond Loewy alumnus who had also designed the gently curvaceous Routemaster bus, London’s other great symbol of well-being. Surely we can all agree that anything connecting Sir John Soane of Lincoln’s Inn Fields with Raymond Loewy of Panorama Road, Palm Springs, is a masterpiece of popular culture.

In a final myoclonic twitch of Empire, the GPO sold its phone boxes to Bermuda, Gibraltar and Malta. I saw my first exotic K2 in Victoria, capital of Gozo. At one level this bright red box, familiar from rainy Whitehall, looked incongruous in front of a scorched and crumbling Sicilian baroque facade. At another level, it was a pleasantly strange reminder of how complicated architectural symbolism can be.

Notes

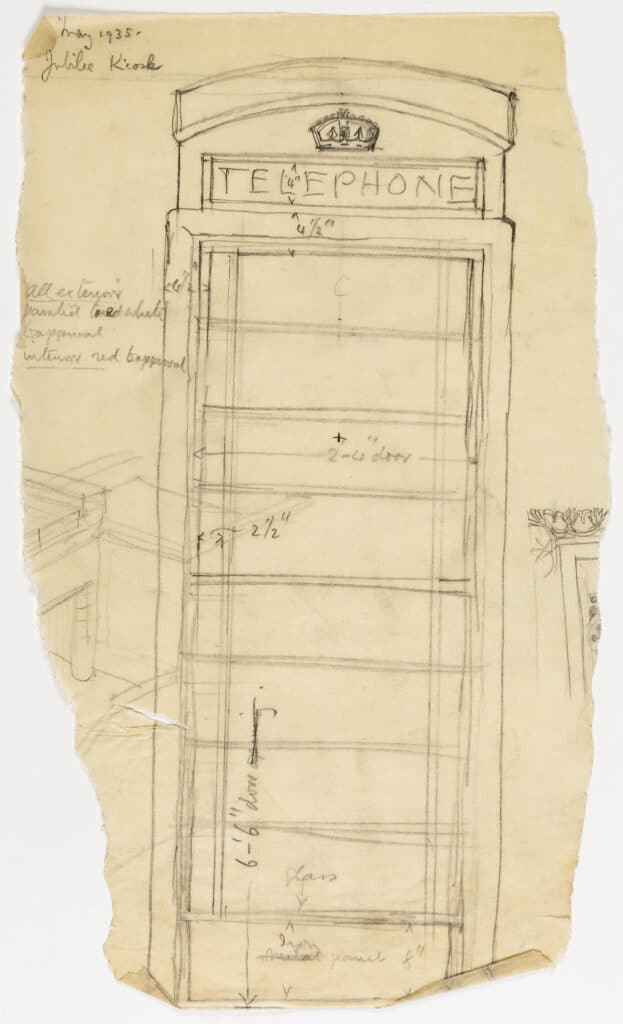

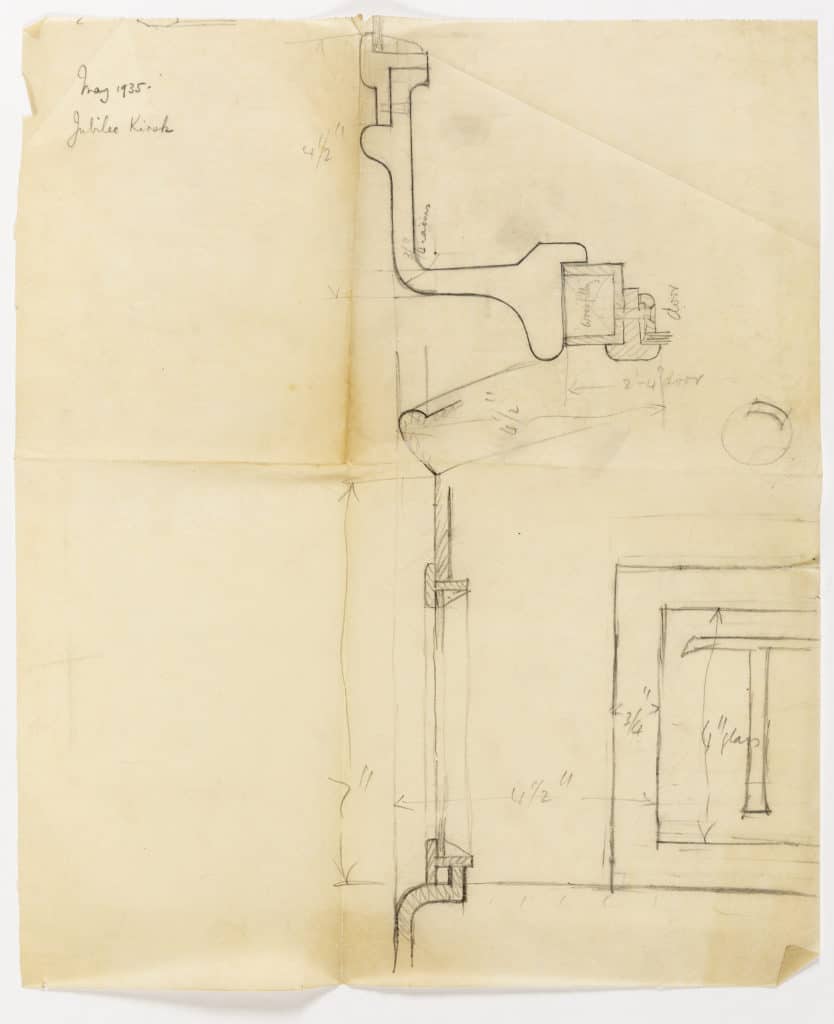

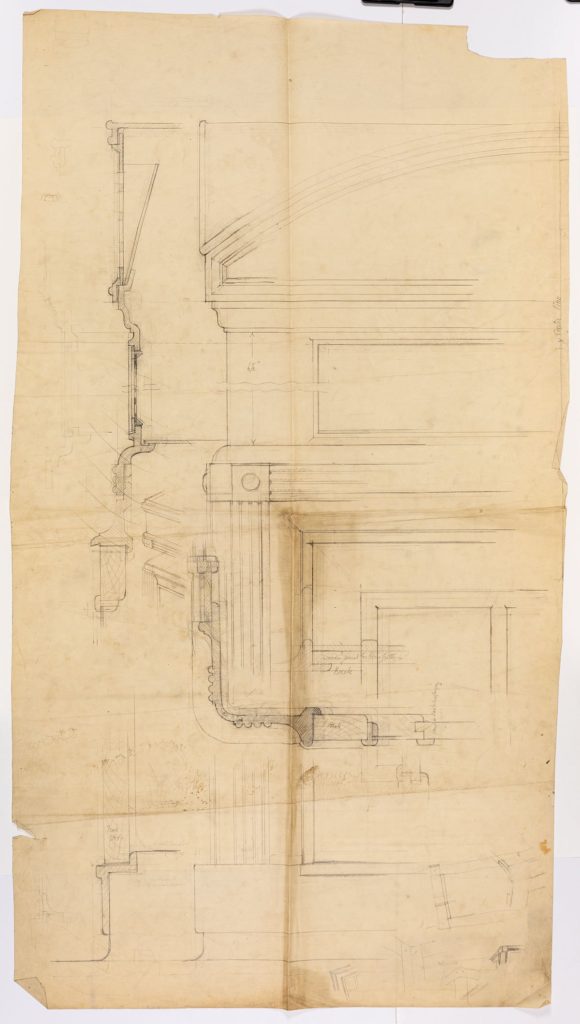

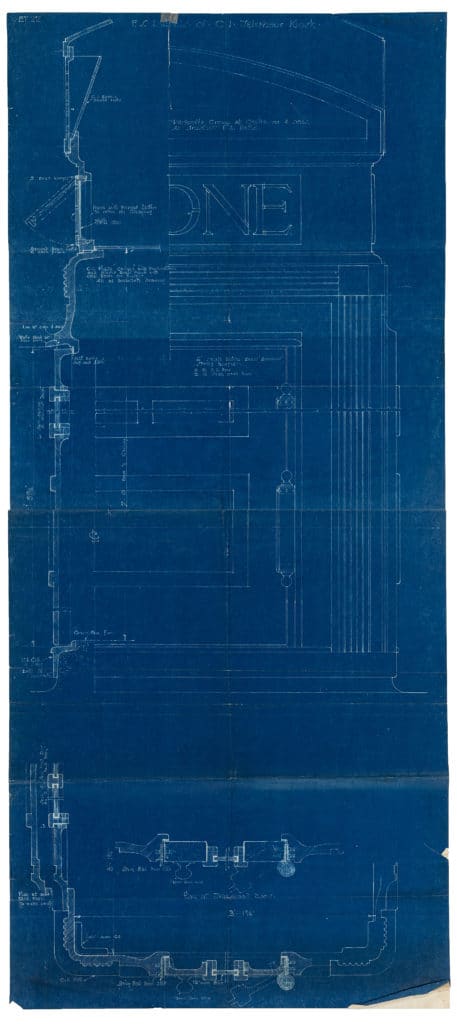

- The drawings here, and now in Drawing Matter collection, show Scott’s designs for the K6, commissioned in 1935 to celebrate the Jubilee anniversary of George V. They offered an answer to the Goldilocks problems caused by the original – too large and expensive – and its immediate successor, the K3, which was too brittle. Thousands of the relatively slimline K6 were installed across the UK any town or village with a post office could apply for one.

– Stephen Bayley