R. Norman Shaw

R. Norman Shaw (1831–1912) is commonly thought of as a domestic architect, but he built a fair number of churches, sixteen altogether, many of them original and remarkable in one way or another. There is an evolution in Shaw’s church designs from the emotional ardour of his earliest efforts, like the great lost Holy Trinity, Bingley, to the calmer, more spacious works of his later years like All Saints, Leek, Staffordshire; Holy Trinity, Latimer Road, West London; and All Saints, Richard’s Castle, Shropshire.

St Margaret’s, Ilkley, of 1878–9, marked the moment when Shaw started to change gear and take his churches in a new and broader direction, under the influence of G. F. Bodley and George Gilbert Scott, Jr. It is a well-documented building. By a stroke of luck, among the 31 letters from Shaw still preserved in the church’s archives is that rare piece of evidence, an architect’s first thoughts about his intentions. In January 1876 he wrote to F. W. Fison, the chairman of the church’s building committee:

‘I send you a preliminary plan of the new church, and a tracing of the sort of thing I would suggest. I am so sick of the everlasting modern church, with its orthodox pitched roof and its feeble spire, and I do think it would come in so badly in your valley that I long to do something that I hope would come in better. I should like to keep it all simple, but as large in mass as possible. Let us save as much money as possible in the items of plinths and cornices and string courses but let us have the walls as high and as thick as we can afford, and let the tower be as bulky as possible, and no very extravagant height. After all there is plenty of room for it in the valley, it won’t choke you up much. I shall be very anxious to hear what you think of this general scheme. I am sure it is mass that tells and not mouldings or architecture. Then you would find it very splendid in effect if you had very few windows in the aisles, and the great preponderance of light coming from the clerestory and from a large west window. I should like to get the windows interesting in their tracery, if I could, as I know grim plain lancets are not much approved of by some of your members. I do sincerely hope you will not think this is too outrageous, but will smile kindly on it, and then I can carry it a stage further.’

Fison and his committee seem largely to have gone along with these ideas, but because St Margaret’s was a church built by subscription, not for a single rich patron, Shaw did not get the grand central tower he hoped for at first (and later built at Leek). Instead he made the church long and to first appearances low, built into the side of a suburban Yorkshire hillside leading up to the Ilkley Hydro, which was then at the height of its Victorian fortunes. It was made large in the hope of accommodating convalescent patients from the spa, but like many churches of its day it can seldom have been full. The materials are dressed local stone, and the style is late Decorated or early Perpendicular, with the broad traceried end-windows Shaw talks about in the letter to Fison. There was a long gap between this letter and the start of works, no doubt because fundraising had to be done. The executed design was made early in 1877, but building did not start till May 1878. The contracting mason was Whitaker of Horsforth, Leeds, and the joinery was by another Leeds firm, J. H. Thorp, whom Shaw also employed elsewhere.

Shaw must have received the Ilkley job because of his excellent connections and track record from the 1860s onwards working for prosperous High Church laymen in the Leeds and Bradford area. His closest local ally and friend was J. Aldam Heaton, who began as a Yorkshire textile designer, moved to London, took up interior decoration and contributed to the fittings of St Margaret’s. Fison, who came from a mill-owning family based at Burley in Wharfedale, seems to have moved in similar circles; at one point Shaw sketched out a grand house for him, probably for Ilkley, but it was never built. Fison was only in his twenties when involved in St Margaret’s; he later became a Tory MP and was made a baronet in 1905.

In terms of surviving drawings, St Margaret’s is well served by eighth-inch-scale plans and elevations in the RIBA and V&A collections, but only one among the main body of his drawings at the Royal Academy. Eleven drawings in a private collection add details to the standard eighth-scale sets, and shed light on Shaw’s long-distance method of working and communicating with his on-site representative at Ilkley. That was Edward S. Prior, later a well-known architect and teacher in his own right. It is from Prior that these more detailed drawings emanate. He must have kept them among his own collections after the Ilkley job was over. They were among a number of architectural drawings inherited by Prior’s grandson, Mr J. C. H. Templar, and given after his death by his executor Dr Peter Smith to Dr Julian Litten FSA in 2003. Most of those drawings have to do with Prior’s own work, but eighteen or nineteen are associated with his time under Shaw.

Prior (1852–1932) had been articled as a pupil to Shaw in 1875. His dispatch to Ilkley as clerk of works on St Margaret’s marked the completion of his articles and a practical period of transition into full status as an independent architect. On several occasions in the 1870s and ‘80s Shaw used clerkships of this kind as finishing schools for his pupils and assistants. Such opportunities seem to have been reserved only for large and important commissions, especially those further from London and so harder for Shaw to visit regularly. If the builder was new to Shaw, as Whitaker seems to have been at Ilkley, that was another reason for having a trusted assistant on site. And indeed, Prior no doubt proved his value, since a settlement took place in some of the piers when construction was nearing completion in July 1879. As we know from two reassuring letters from Shaw that summer, Fison showed some tendency to panic about this, but Prior was on the spot to watch, direct the shoring-up, and make sure the settlement had stopped.

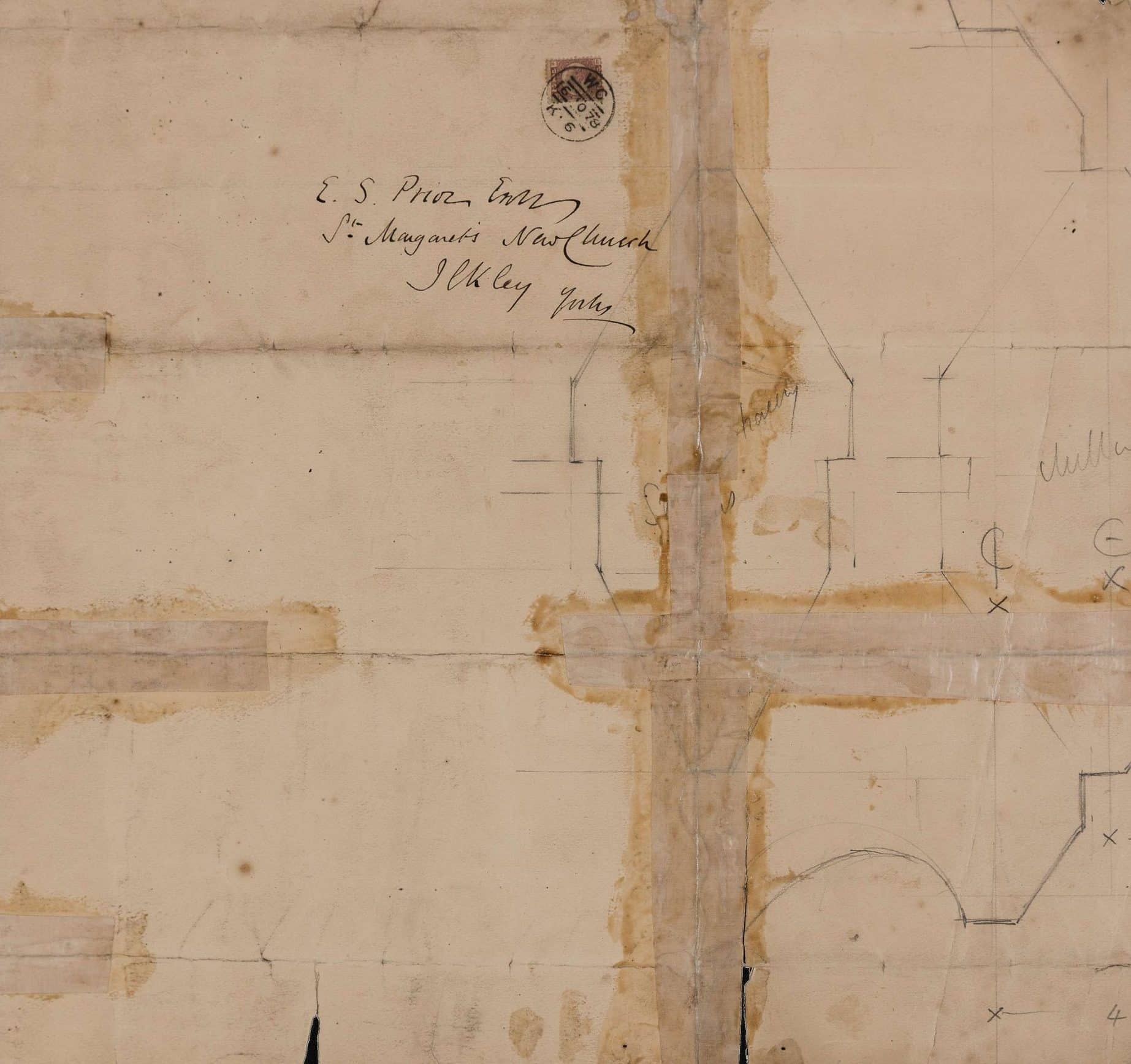

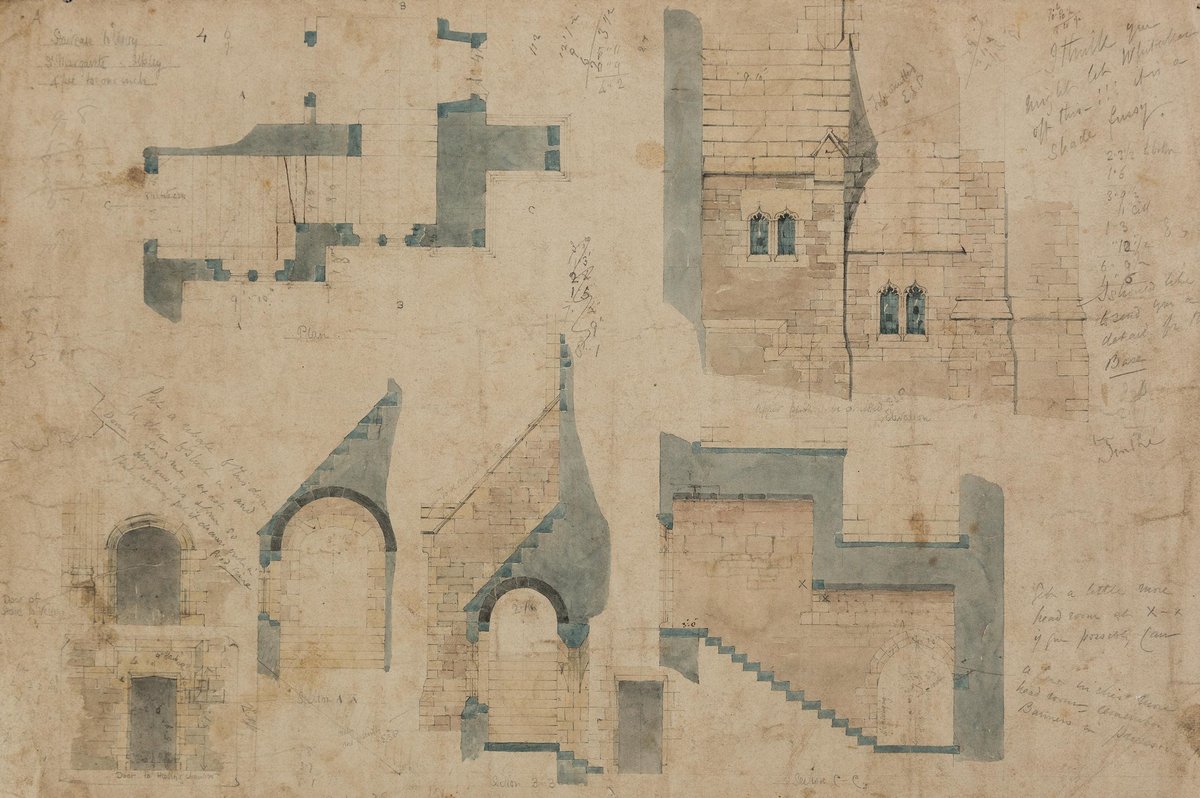

The eleven drawings, all of which are details, appear to date from 1878–9, in other words from the period of construction when Prior was on site. Not all are dated, but of those that are, the earliest is of October 1878 and the latest of April 1879. Most of them appear to be details drawn out by Shaw in London, folded up and posted to Prior in Ilkley with a stamp on the back instead of an envelope (see 1v.). This was common practice in Shaw’s office at the time, and probably that of others. Such drawings were regarded as ephemeral working documents, which might be copied or handed on to the builder according to circumstance. All but one appear to have been made on standard stout cartridge paper.

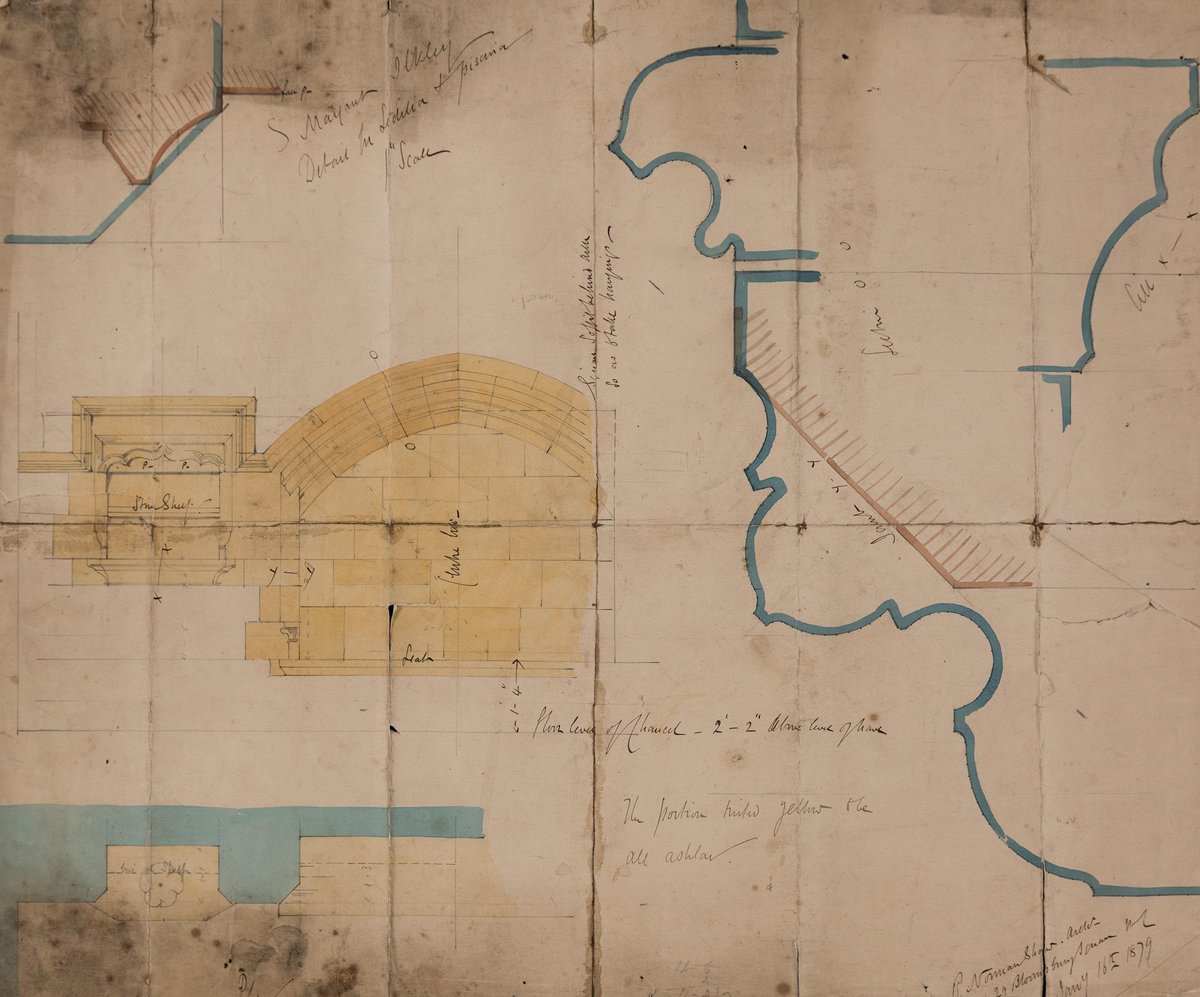

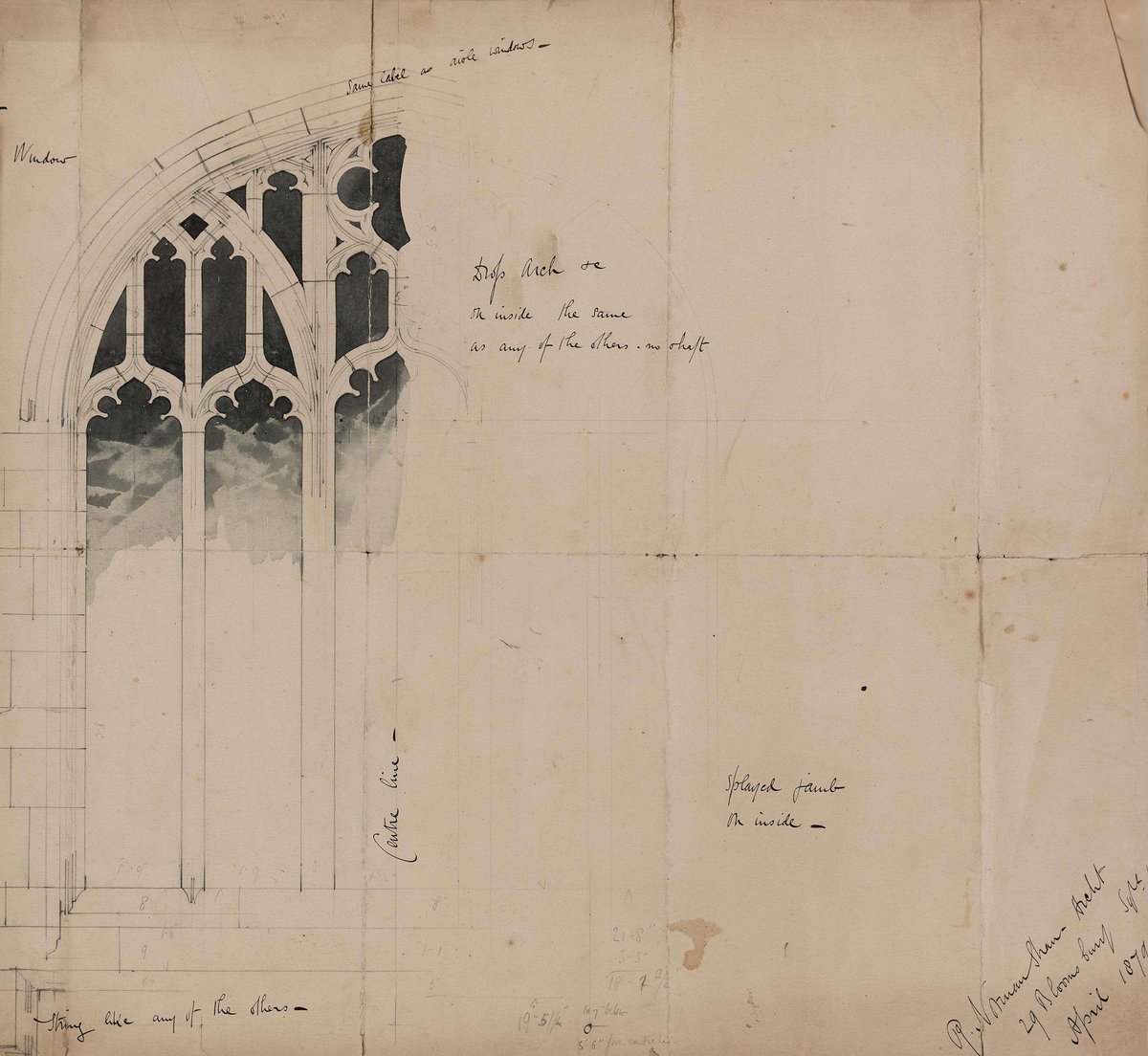

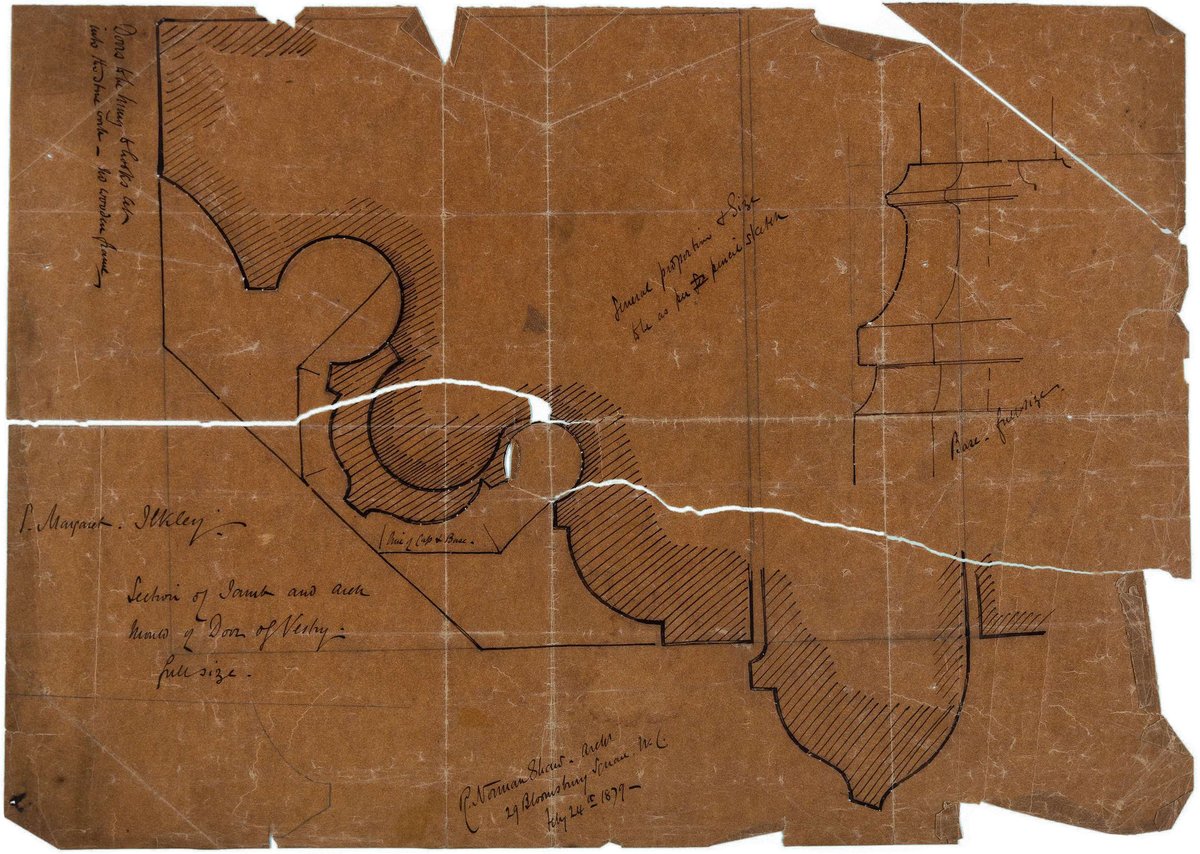

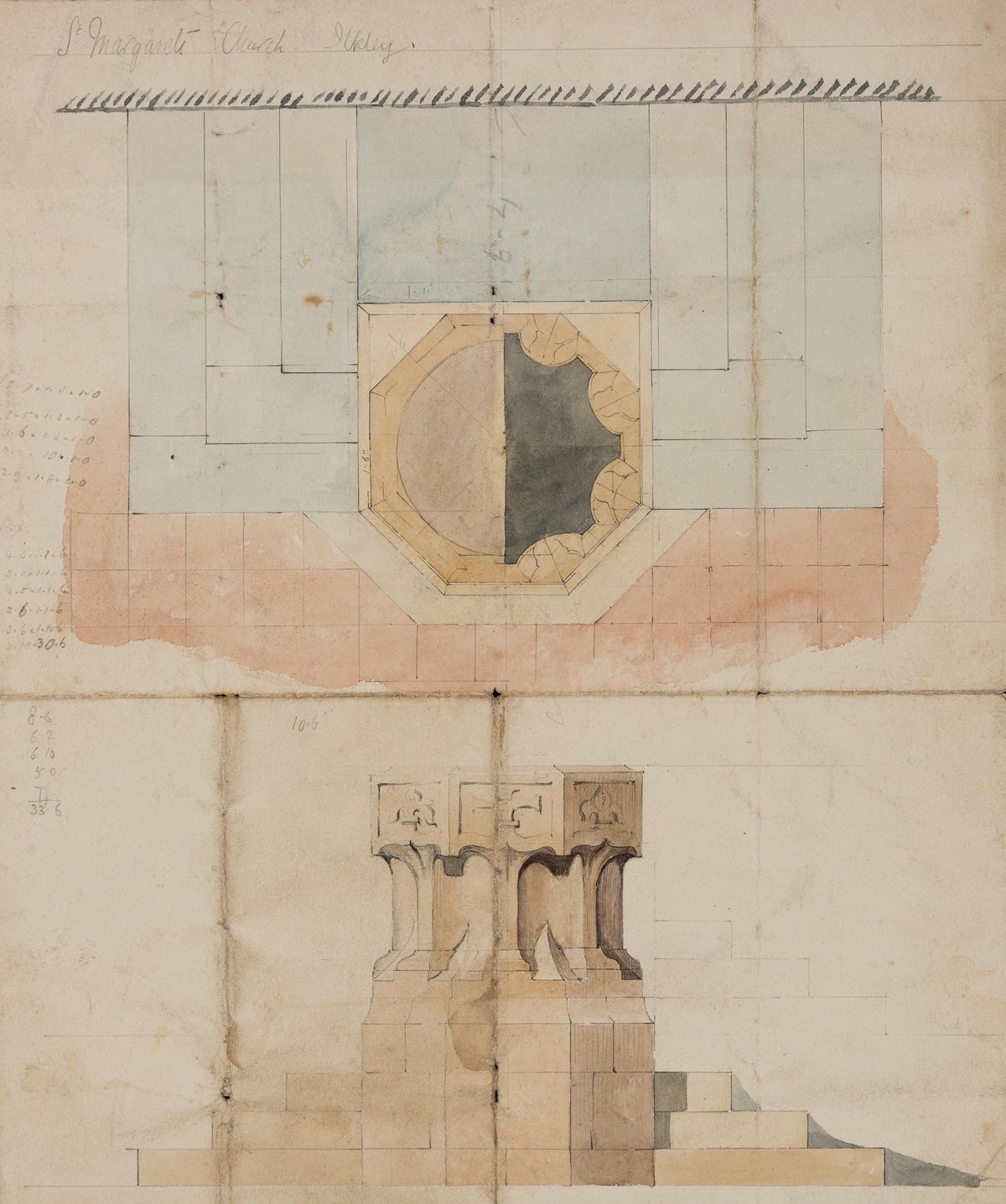

The drawings are mostly in pencil and wash; the exception is No. 7, of pen on tracing paper. Most are quite easy to interpret. Nearly all have to do with the east end of the church, where the land dropped, the vestries were built under the chancel and the details were generally more complex. No. 4 (inscription cut off) appears to be for the five-light transept windows. No. 1r (no label) is a bit of a puzzle. The left-hand side draws out the fine tracery of the east window, but right of centre different tracery patterns are shown, with an intrusive cusped quatrefoil. I wonder if the right-hand side shows the tracery for the west window, likewise of nine lights?

The majority are in Shaw’s hand, as is clear from his confident handwriting. But one or two may be Prior’s. No. 6, which shows two two-light windows, one arched, the other straight-headed, has a scrawly inscription at the top which appears to read ‘St Margarets’; this might be Prior’s. No. 9, a drawing for the font is more certainly from his hand. Shaw gave his trusted assistants a free hand with certain details of his buildings when he felt he could, and it has always been guessed that the rather gawky font at Ilkley, dissimilar from any other in a Shaw church, was given to Prior. Most of the fittings at St Margaret’s were added in later because of lack of money at the time of consecration, so in 1879 the font would have had special importance. The wash technique and the shading on this drawing make it rather different from the others. No. 5 also has rather different handwriting from Shaw’s at the bottom, but of course such inscriptions prove little or nothing.

The drawings also demonstrate Shaw’s relaxed, almost collegiate style of detailing his buildings, in which contractor and clerk of works played their part. That is quite different from the methodology of, say, Butterfield or Philip Webb, for whom drawings are rigid instructions, no more and no less. So on No. 8 (staircase to vestry) Shaw sketches in the plan of a door opening beside the finished drawing and writes: ‘Put a rebate to this door (a door to shut in) and send me exact dimensions and form so that we may get it drawn out in good time’. On No. 2 he writes: ‘Label to be same as some of the others or slightly altered’. On No. 4 he writes: ‘String like any of the others’. The closest equivalent I know to these clear but easy-going instructions are some of the drawings in the RIBA collection for houses Shaw had built by a trusted builder, Frank Birch, on which he writes in similar vein: ‘The barge boards cornices etc to be all similar to Wispers – or Boldre Grange or any if our best specimens’; and on one occasion he exclaims; ‘Get some headroom in here somehow’!

– Niall Hobhouse